(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Well-built buildings, large and small, picturesque and plain, can often be recycled for new uses. While the American historic preservation movement began by saving patriotic sites such as General George Washington’s Revolutionary War headquarters in Newburgh, New York in 1850 or Washington’s own home, Mount Vernon, in 1858, not every historic building is a candidate for expensive restoration and museum-quality interpretation. As members of the preservation movement grew to appreciate not just single buildings but also large swathes of neighborhoods or communities, the number and types of structures they documented as worth saving increased. People involved in the movement also came to recognize that industrial buildings and mill towns, schools, churches, and vernacular buildings such as barns and farmsteads resonate with some aspect of local history.

But, as society changes, buildings sometimes become obsolete. Mills produce products that are no longer needed, changes to the education system make older school buildings unsuitable for today’s teaching standards, and smaller religious congregations often don’t need the large seating capacity of churches that welcomed waves of immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries. Occupants move on, and leaving vacant buildings at risk for demolition.

In light of the possibility of losing landmark buildings, “adaptive reuse” has become an important strategy. Akin to recycling, adaptive reuse seeks to find a new use for a historic vacant building. New England, and certainly Connecticut, has been in the forefront in converting old brick mills, once used to make products ranging from horse nails to carriages, into housing and office space, sometimes encompassing thousands of square feet in a single project. But much smaller projects often show the same level of innovation and creativity. A fire station becomes a theater, a barn now houses a human family, a post office serves as a restaurant, and a department store is transformed into artist housing. Larger projects sometimes benefit from government tax credits or grants, while many smaller ones depend mostly on private funds.

The built environment is a reservoir of community memory, of historical significance, of architectural beauty, and of building materials. Architect Carl Elefante is credited with the nationally known phrase “The greenest building is the one already standing,” a notion that aligns the rehabilitation of existing buildings with the “green,” sustainability movement. Demolition wastes the energy used to make the original materials and unnecessarily crowds our landfills.

Adaptive reuse projects require a certain amount of vision and ingenuity. As you turn the next few pages of the magazine, think about how many buildings you encounter in your everyday life that have been transformed from their original purpose to serve us in the 21st century—and how much they contribute to the character and charm of your community.

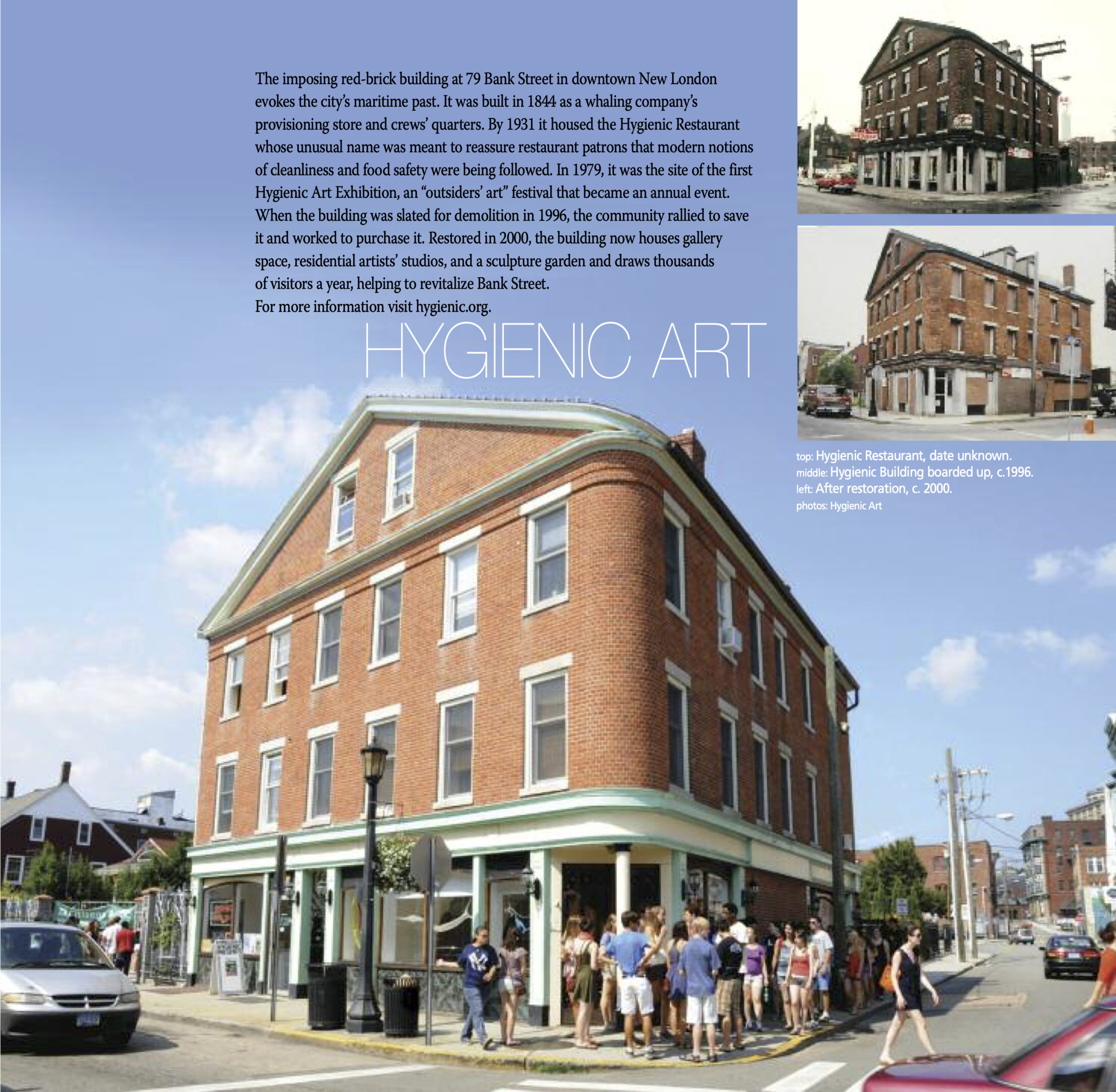

The imposing red-brick building at 79 Bank Street in downtown New London evokes the city’s maritime past. It was built in 1844 as a whaling company’s provisioning store and crews’ quarters. Housing the Hygienic Restaurant by 1931, its unusual name was meant to reassure restaurant patrons that modern notions of cleanliness and food safety were being followed. In 1979, it was the site of the first Hygienic Art Exhibition, an “outsiders’ art” festival that became an annual event. When the building was slated for demolition in 1996, the community rallied to save it and worked to purchase it. Restored in 2000, the building now houses gallery space, residential artists’ studios, and a sculpture garden and draws thousands of visitors a year, helping to revitalize Bank Street.

An unused 7,000 square foot dairy truck garage was transformed into a community theater with a lobby, stage, seating, and dressing rooms by architect Richard Hughes in [year]. The playhouse sits next to A.C. Petersen Farms’s Art Deco-style restaurant and former milk production plant built in 1939. The demise of home milk-bottle delivery starting in the 1960s left the garage vacant and ready for re-use. The 168-seat playhouse’s three-sided stage offers professionally produced plays, stand up comedy performances, and children’s productions year-round. The playhouse enlivens a neighborhood hub of restaurants and local shops.

244 Park Road, West Hartford

The Dye House

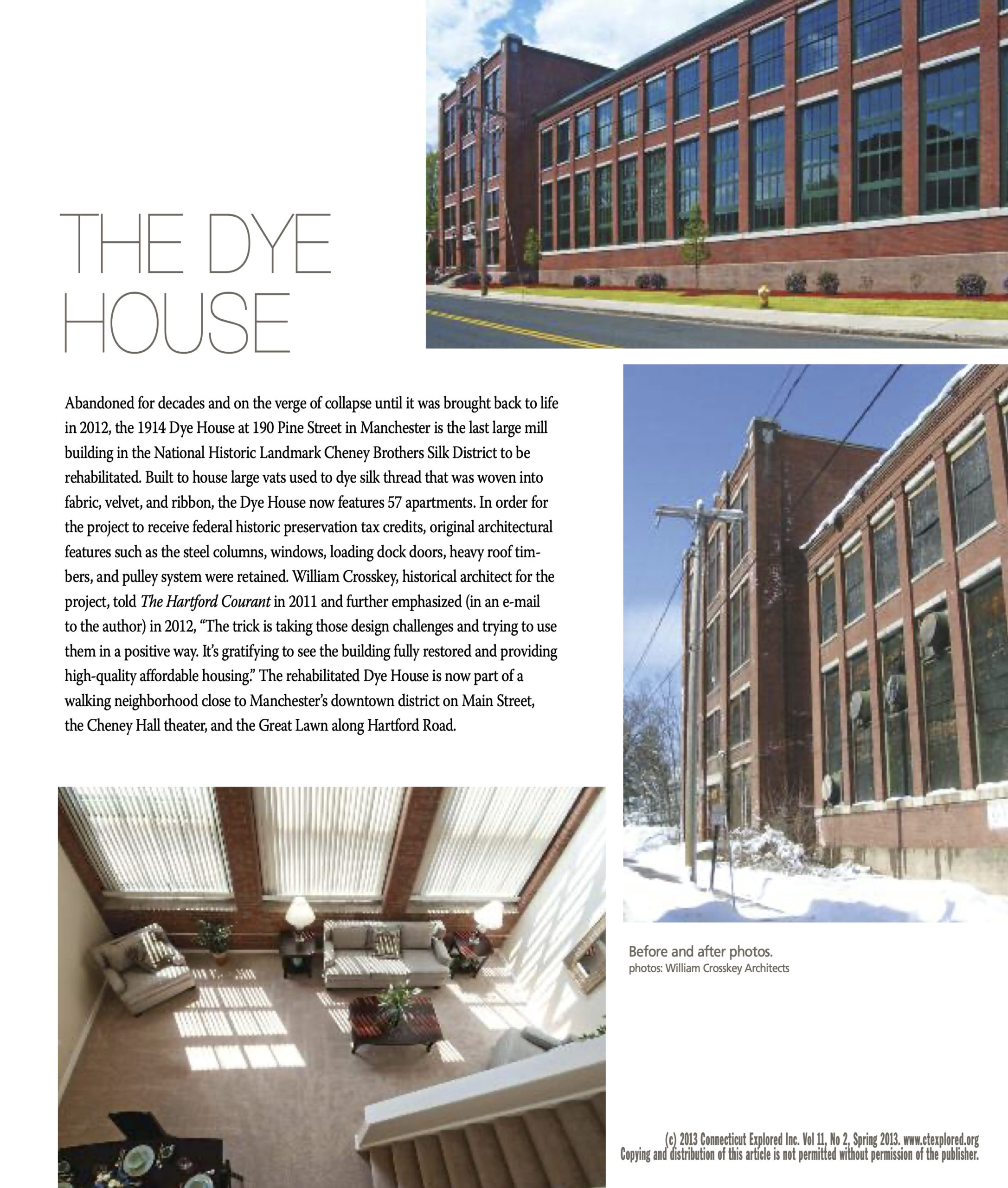

Abandoned for decades and on the verge of collapse until is was brought back to life in 2012, the 1914 Dye House in Manchester is the last [the rest were torn down?]large mill building in the National Historic Landmark Cheney Brothers Silk District. Built to house large vats used to dye silk thread that was woven into fabric, velvet, and ribbon, the Dye House now features 57 apartments. In order to receive federal historic preservation tax credits, original architectural features such as the steel columns, windows, loading dock doors, heavy roof timbers, and pulley system were retained. William Crosskey, historical architect for the project, told The Hartford Courant in 2011 and further emphasized (in an e-mail to the author) in 2012, “The trick is taking those design challenges and trying to use them in a positive way. It’s gratifying to see the building fully restored and providing high-quality affordable housing.” The rehabilitated Dye House is now part of a walking neighborhood close to Manchester’s downtown district on Main Street, the Cheney Hall theater, and the Great Lawn along Hartford Road.

ARETHUSA FARM DAIRY RETAIL STORE AND CREAMERY

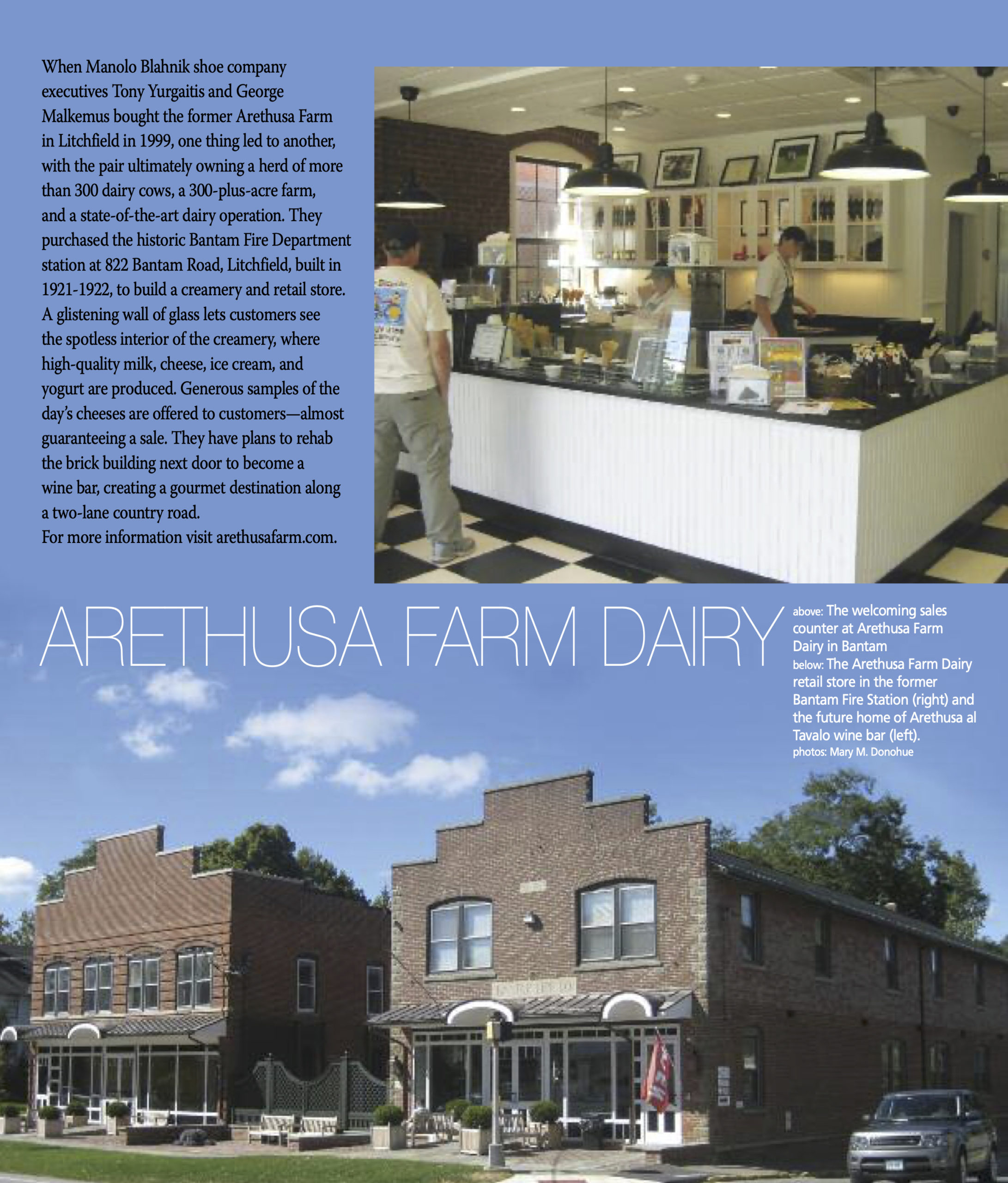

When Manolo Blahnik shoe company executives Tony Yurgaitis and George Malkemus bought the former Arethusa Farm in Litchfield in 1999, one thing led to another, with the pair ultimately owning a herd of more than 300 dairy cows, a 300-plus-acre farm, and a state-of-the-art dairy operation. They purchased the historic Bantam Fire Department station, built in 1921-1922, to build a creamery and retail store. A glistening wall of glass lets customers see the spotless interior of the creamery, where they produce high-quality milk, cheese, ice cream, and yogurt. Generous samples of the day’s cheeses are offered to customers—almost guaranteeing a sale. They have plans to rehab the brick building next door to become a wine bar, creating a gourmet destination along a two-lane country road.

822 Bantam Road, Bantam, Litchfield

arethusafarm.com

Vernon Community Arts Center

Known most recently as the Kindergarten Building, the town-owned Vernon Community Arts Center was built in 1927 as the County Home School for children. Closed as a school in 1950, the building was then used for kindergarten and adult classes by the town and later for storage. A typical Colonial Revival-style school with small-paned windows and wainscoted classrooms, the building could easily have been lost without a new vision for its future. A $1.7-million investment by the town and state has created 2,500 square feet of gallery, classroom, and performance space. Dedicated in June 2012, the Arts Center has a full schedule of events and activities planned for its first year.

709 Hartford Turnpike, Vernon

vernonarts.org

Mary M. Donohue was executive director of the Manchester Historical Society and guest editor of the Spring 2013 issue of Connecticut Explored. She is an author, lecturer, member of the CT Explored editorial team, and frequent contributor to the magazine.

Read More!

Read more Historic Preservation stories on our TOPICS page.