(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2017

On September 22, 2017 the community will mark the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Hartford chapter of the NAACP (National Association for the Advancement of Colored People). New Haven’s branch also celebrates its 100th anniversary this year.

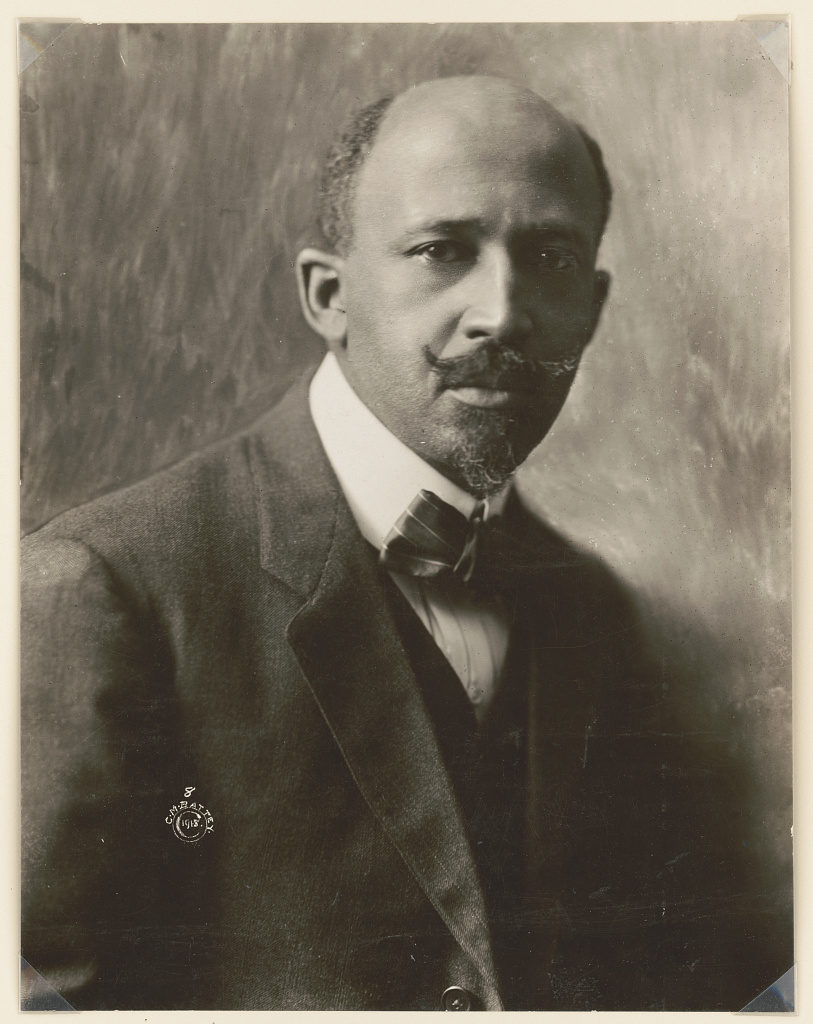

The NAACP was founded in New York City in 1909. It was formed partly in response to the problem of lynching in the South and the 1908 race riot in Springfield, Illinois. Appalled at the violence against blacks, a group of white liberals that included Mary White Ovington, Oswald Garrison Villard, William English Walling, and Dr. Henry Moscowitz called a meeting to discuss racial justice. Some 60 people, 7 of whom, including W.E.B. Du Bois, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, and Mary Church Terrell, were African American, signed the call, which was released on the centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth.

The beginnings of the Hartford branch date to a small gathering in 1917. Mary Townsend Seymour, a dedicated freedom fighter in the Hartford African American community, hosted 20 prominent black and white leaders at her home at 420 New Britain Avenue. The group discussed better ways of integrating thousands of recent African American migrants from the South into Hartford’s community. [See “Southern Blacks Transform Connecticut,” Fall 2013, and “Audacious Alliances,” Summer 2003.] Seymour conceived of the organization as an “organization of Americans of all races, creeds, and colors.” For a century members of the Hartford branch have tirelessly and bravely fought against racial violence and discrimination in its myriad forms, locally and nationally.

In November 1917 DuBois, Ovington, and James Weldon Johnson, all prominent leaders within the national office, visited Hartford to address a large meeting at Center Church. When he took the podium, DuBois, who had learned that an attempt might be made to segregate African American students in the city, boldly announced his opposition to any such effort.

On December 10, 1917, the national organization’s board, clearly impressed by the local activism and organizing spirit in Hartford, granted the Hartford branch a permanent charter. William Service Bell, a respected African American clerk at a local merchandise store, became the branch’s first president, while Seymour served as vice-president.

Bell announced his agenda with an unflinching voice. Bell, who later served in World War I, let the community know through statements in the local newspaper that he vehemently opposed the “ghoulish crime” of lynching, supported self-defense efforts, and supported expanded rights for African Americans in Connecticut. In April 1919 the Hartford and New Haven NAACP branches came before the Connecticut Legislative Judiciary Committee to request that the state enact a civil rights bill. In August, Bell expressed his concern about the possibility of attacks similar to lynching by whites on African Americans in Connecticut. He notified Du Bois about efforts to build a local organization of African American veterans and others as a protective force against potential attacks by white citizens.

In 1923 Seymour, now president, and Lucy C. Brooks, secretary of the local branch, urged that major newspapers such as The Hartford Courant accord African Americans respect by capitalizing the word Negro and ending “undue racial characteristics” of people of African ancestry. They argued that the word Negro needed to be capitalized just as “American, Irishman, Englishman, Indian, or Hindu, and their consistency and thoughtfulness are appreciated.”

In the 1930s local branch members continued to come to the aid of migrating Southern African Americans, challenged white politicians to support anti-lynching legislation, and confronted employment issues in the city. In 1930 the Hartford branch rallied behind an African American resident accused of rape when it learned that he might be extradited to the South by Alabama law-enforcement officials. Branch members thought that regardless of guilt or innocence the accused had a “slim” chance of a fair trial in the Alabama of 1930. Key members of the organization met at the home of Walter R. Johnson, branch secretary, with African American Attorney Howard P. Drew to offer legal and financial support to the accused.

Dr. John C. Jackson (center) was branch president in the early 1930s. Rabbi Morris Silverman (l) chair of the Inter-racial Commission, and Hartford Public Library librarian Magnus Kristoffersen (r), February 25, 1950. The Hartford Times, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Branch members sent questionnaires to Connecticut candidates seeking election to the U.S. Congress asking whether they supported anti-lynching legislation. They met with some success in getting promises of support. In 1930, for example, one candidate running to represent Connecticut in the U.S. House of Representatives, Colonel Clarence W. Seymour, informed R.H. Burt, editor of the local African American magazine the Mouthpiece, that he would “vote for any anti-lynching law which the colored people may wish me to support.”

By 1938 the Great Depression was in full swing. Concerned about unemployment among African Americans, the Hartford branch held a forum called “What I Think the NAACP Should Do about the Unemployment Situation.” Branch members were part of a national effort to confront defense-industry contractors with hiring practices that discriminated against African Americans.

Dr. Allen F. Jackson and Hartford’s NAACP, 1937 – 1945

In 1937 the Hartford chapter experienced one of its most profound changes. Dr. Allen F. Jackson, a local physician and graduate of Howard University Medical School, was elected branch president. Dr. Jackson worked to increase membership in the branch, strengthen ties to the national group, and make the organization more viable. In October 1943 W.R. Burden Sr., local branch secretary and a white attorney from West Hartford, informed Walter White, executive director of the national organization, that Hartford’s local now boasted 934 members and could soon reach 1,000. Funds raised through membership campaigns helped the national organization mount major campaigns to decrease housing and employment discrimination.

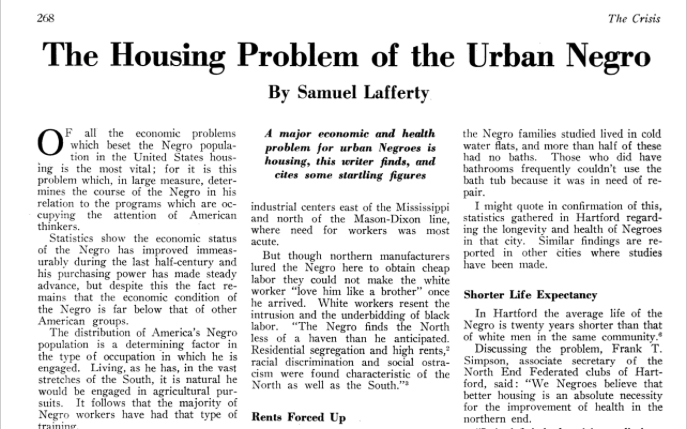

Frank T. Simpson was quoted, “We Negroes believe that better housing is an absolute necessity for the improvement of health in the northern end [of Hartford.]. The article notes that the average life expectancy of African Americans was 20 years shorter than that of white in Hartford. The Crisis, September 1937

Internal Strife and Renewed Focus, 1946 – 1958

The 1946 election revealed a fissure in the organization over election of new officers for the executive board. Although Percy Christian, the newly elected president, was not an “educated” man, member Eleanor Hope Johnson found him energetic and committed to the NAACP. But she informed Ella Baker, a leader in the national office, of a feud among members. Baker urged the members to refocus their efforts, arguing that the group could “ill afford to dissipate their energies in internal strife.” As the legendary civil rights leader urged, the local refocused on the work at hand.

Under Percy Christian’s leadership, the branch quietly pushed for passage of legislation to create a permanent Federal Employment Protection Committee (the Roosevelt-era committee charged with reducing discrimination in employment), argued against segregation, fought for jobs, and supported the national organization’s request for legal funds. Locally, the branch urged the city and its businesses to hire African Americans as fire fighters, bus drivers, telephone operators, and doctors. The organization’s Legal Redress Committee conducted detailed investigations of local discrimination in hiring and mailed protest letters to New Britain and Hartford city leaders. When the national made a request for donations for legal funds for this work, local branch members proudly sent $300 to New York.

Christian stepped down after three years at the helm. In 1949 Minnie Wheatle Pierce was elected to lead the Hartford branch. She led the local in confronting efforts by Southern bigots to prevent the passage of a civil-rights bill. In a January 1, 1949 letter to Senator Baldwin, Pierce requested that he “help put an end to the Senate bill governing filibuster.”

Ever persistent in recruiting and maintaining membership, in 1950 the local continued to set its sights on improving housing for African Americans. By 1958 the local NAACP interviewed more than 300 families about their housing situation. Their study revealed that rental funds that helped to pay for housing for poor African American people went into the pockets of white landlords and businessmen outside of black Hartford. Reports surfaced of dwellings that were disgracefully in need of repairs.

The “Windsor Street Riot”

On the night of July 19, 1958, a melee between police and African American residents ended after the city brought eight police cars and 20 officers to the 200 block of Windsor Street to quiet a group of 500 to 700 people. The unrest was caused by an altercation between a police officer and a local African American resident. Hartford branch president Arthur Johnson and members of the NAACP focused their attention on police conduct and the fair and equitable treatment of those arrested. The branch considered the bonds levied to those arrested “improper,” and police-officer conduct at the arrest of one African American “abusive.” Their efforts resulted in reduced charges for those arrested. The harshest punishment meted out was a jail sentence of 15 days.

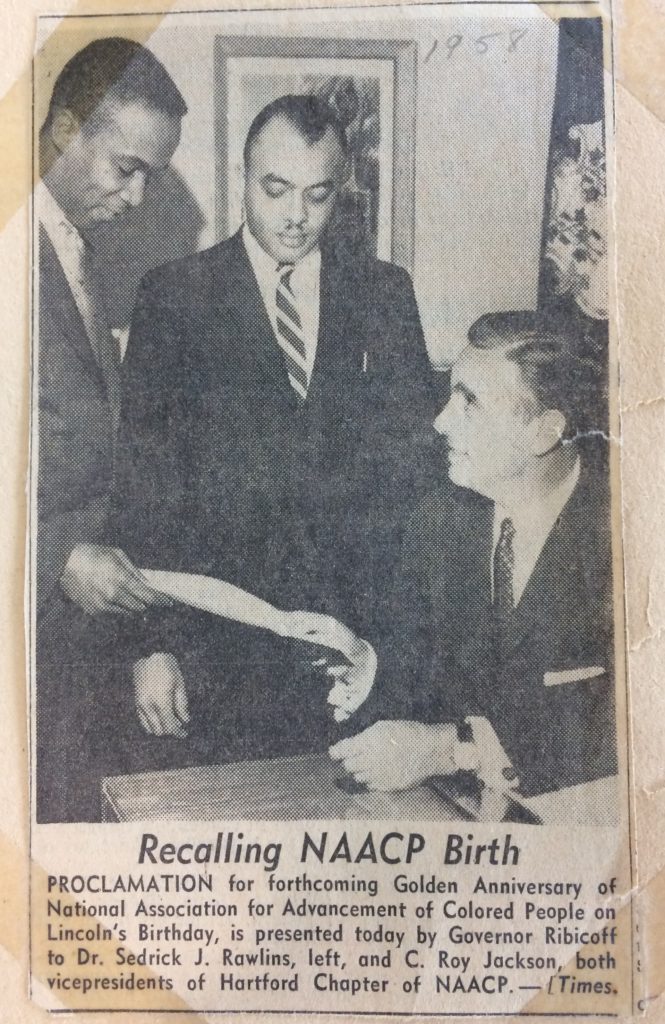

Dr. Sedrick J. Rawlins and C. Roy Jackson, vice presidents of the Hartford NAACP chapter, accept a proclamation honor the chapter’s 50th anniversary from Governor Abraham Ribicoff, 1959. Both later served as branch president. Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Hartford’s NAACP, 1961- 1968

The Hartford Courant reported on June 25, 1961 that police had raided the Bottom News and Raleigh Smoke Shop, a North End business on Windsor Street for allegations of illegal gambling. Police arrested 44 North End residents. After the local NAACP received complaints of discrimination, the organization, led by C. Roy Jackson, investigated the complaints that argued that those arrested had entered the shop, not to gamble, but to make legitimate purchases. Jackson submitted a three-page statement with findings and recommendations for addressing those complaints to Councilman George Ritter. One of the major suggestions was the establishment of a Police Advisory Board. Other concerns included charges that the police placed arrested African American women in the same cell block with men. The police argued that no matron existed to watch the women, but the NAACP noted that the women’s cell block already had one female prisoner and that the police moved an African American woman to the women’s cell block only after no space existed in the men’s cell block.

On September 15, 1963, the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama tragically reminded many people in the country about the price that African Americans often paid in their quest for freedom and equality. In response to the bombing, Hartford’s North End Community Action Program (NECAP) and NAACP leaders held a midnight rally of 150 people at the Federal Building in Hartford. The marchers wanted justice for the murdered youngsters, those injured, and their families. NECAP and NAACP leaders contacted Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. for his advice and the administration of John F. Kennedy to ask for federal intervention in Alabama.

Demonstration in Barry Square, 1967. The Hartford Times, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

As the national movement increased its militancy, Hartford’s NAACP nurtured and developed young leaders. In Wilber Smith they found a leader who appealed to the poor, young people, and the quickening pace of the movement. The energetic Smith brought an air of militancy and urgency to the NAACP. Smith, a native of Florida, quickly became arguably the city’s most confrontational NAACP activist. He began his Hartford career in the NAACP with the local Youth Council. Ella Cromwell, a NAACP stalwart, and other leaders trained and recommended Smith for leadership in the organization.

With a fierce urgency propelling its actions, throughout 1964 Hartford’s NAACP used its voice in the street to promote its annual fund drive. For more than a year Thomas Parrish and his partner at a local gas station played speeches by Rev. Martin Luther King over a loud speaker at Main and Pavilion streets. One donation came from Lucy Brown, who made her money by collecting trash and junk to sell. When she died, Brown left the NAACP the hefty sum of $1,000. The national and local used the funds given by Brown and others to pay the bail for those arrested in protests in the South and additional campaigns.

The organization also organized a protest against the U.S. Postal Service. On May 12, 1965, NAACP, NECAP, Urban League, and Connecticut Race and Religious Action Commission initiated a three-day protest of UPS for discriminatory actions. The UPS protest paid dividends in the form of jobs for African Americans.

After an unknown assailant set a bomb that killed Natchez, Mississippi branch treasurer Wharlest Jackson there in February 1967, Hartford branch members both solicited and donated funds for the care of Jackson’s family. By that summer, though, tensions in Hartford reached the breaking point.

The rebellion, as black power leaders termed it, began as a result of the arrest of William “Billy” Toules, a local African American resident. Other young African American residents who witnessed the arrest charged that the police committed misconduct. Young people took to the streets. Lt. Theodore Napper, an extremely well respected African American police official, said: “I always used to say it could never happen in Hartford.” On July 12, 1967, three days of rebellion swept the North End. Once night fell, groups of young rebels used bricks, firebombs, and rocks to send their message of outrage.

Unwilling to abandon young people, the local NAACP leadership doggedly defended youth they thought were wrongly accused and arrested, criticized the city for slights on poverty issues, and publicly connected with national black-power leaders and other young people perceived as militants. The local NAACP challenged the constitutionality of state laws on breach of peace and inciting riots.

The following year, Hartford’s NAACP and its members dealt with the tragic loss of Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. On April 4, 1968, word of King’s assassination moved throughout Hartford and the rest of the nation. The depth of the pain felt in the North End clearly echoed the hurt that resonated throughout the nation. When he found his voice to address Dr. King’s assassination, Wilber Smith argued that the nation should be ashamed of the racism that created the assassin.

1970 – Present

The 1970s and 1980s saw the local branch soldiering on to confront an evolving discrimination in the region. Branch members also began to reflect on the standing of the organization. At a June 1972 meeting branch members voted to “oppose any publicly funded projects” that lacked inclusion of minorities. In 1981 James W. Patterson, local branch president, led efforts demanding that Frank J. Longo Sr., candidate for mayor in Bristol, apologize after he announced that he had blocked public housing in the 1970s because he feared an influx of poor African Americans.

In a 1988 Courant article several members offered their views on the status of the organization. While the organization focused on education, employment, and legal redress, branch president Barbara Fuller said that the approaches used to solve problems needed to change with the times. Dr. Benjamin Foster, an educator with the state vocational system, said, “People who did stand out and do those kinds of things have gotten older. Some have moved out of state, some have moved to the suburban areas, some have moved to professional lives.”

The discussions regarding the standing of the local branch led to a changed and reenergized organization. By 1989, with Dr. Walter H. Dean as president, membership reportedly increased by 25 percent, and the number of subcommittees rose from 6 to 18. Local branch members also carried a full group of agenda items to the national convention in Detroit.

NAACP leadership clearly understood the difficulties of running an organization in a rapidly changing society. In 2000 and 2002, respectively, former Hartford mayors Thirman L. Milner and Carrie Saxon Perry won the presidencies of the local branch. Milner, though ill, saw a need to lead the organization at a very crucial period, while Perry’s victory brought recognized leadership to the branch. Issues of quality education for African Americans and the need for increased entrepreneurship among minorities in the city remained ever present. Like the leadership within the state branch, the NAACP anguished about violent crime in Hartford, racial profiling, police shootings, and unemployment. In 2005 Hartford’s branch joined with other Connecticut branches to provide support for the citizens of Gulfport, Mississippi that saw their community ravaged by Hurricane Katrina.

In 2011 Imam Abdul-Shahid Muhammad Ansari, president of the Greater Hartford branch, attended a meeting with Police Chief Darryl Roberts, Senator Eric Coleman, and Scot X. Eisdaile in which the NAACP leadership informed Roberts that they planned to monitor the police department’s investigation of the police stop of Connecticut Treasurer Denise Nappier. The branch also continued its outreach work with young people. Working with the state organization and school systems, in 2015 the Greater Hartford branch collaborated to bring 3,000 young people to hear a “Great Debate” between Howard University and Harvard University at First Cathedral in Bloomfield.

Outside of the African American church in Hartford, few, if any, other African American-led local organizations can lay claim to 100 years of service in the freedom struggle. The 100 years were not without inner turmoil and disagreements; all freedom organizations encounter such things as they struggle to survive and maintain freedom. Over the years the Greater Hartford branch’s membership came primarily from the ranks of the membership of African American churches. The churches, such as Union Baptist, Faith Congregational, and Metropolitan A.M.E. Zion, allowed the local branch to use their spaces for programs and meetings. In short, members and leaders in the local persevered in large part because of the foundation upon which they built their organization in 1917. While its membership mostly included African Americans, Mary Townsend Seymour noted that the organization was open to all people, and it was. From its very beginning, the branch battled racism and discrimination in its myriad forms in everyday life, employment, housing, and education. In 2017 the current endeavors of the Greater Hartford branch, now led by Imam Abdul-Shahid Muhammad Ansari, reveal a mission, objectives, and vision that have held true to the foundation established by William Service Bell and Mary Townsend Seymour.

Outside of the African American church in Hartford, few, if any, other African American-led local organizations can lay claim to 100 years of service in the freedom struggle. The 100 years were not without inner turmoil and disagreements; all freedom organizations encounter such things as they struggle to survive and maintain freedom. Over the years the Greater Hartford branch’s membership came primarily from the ranks of the membership of African American churches. The churches, such as Union Baptist, Faith Congregational, and Metropolitan A.M.E. Zion, allowed the local branch to use their spaces for programs and meetings. In short, members and leaders in the local persevered in large part because of the foundation upon which they built their organization in 1917. While its membership mostly included African Americans, Mary Townsend Seymour noted that the organization was open to all people, and it was. From its very beginning, the branch battled racism and discrimination in its myriad forms in everyday life, employment, housing, and education. In 2017 the current endeavors of the Greater Hartford branch, now led by Imam Abdul-Shahid Muhammad Ansari, reveal a mission, objectives, and vision that have held true to the foundation established by William Service Bell and Mary Townsend Seymour.

Stacey Close is professor of history at Eastern Connecticut State University and co-editor of African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014). He last wrote “Southern Blacks Transform Connecticut,” Fall 2013.