By Stacey Close

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. FALL 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

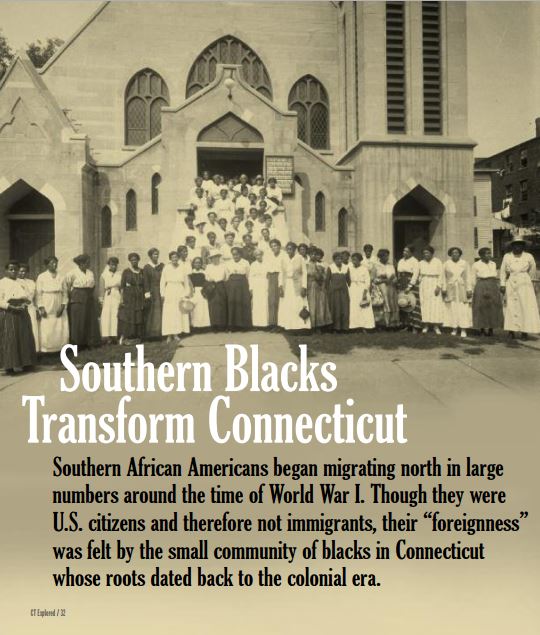

When thousands of Polish, Lithuanian, and Czech workers left Connecticut to return to Europe to fight in World War I, New England tobacco growers urgently tried to locate a replacement labor force. After some initial missteps, the association turned to the National Urban League, one of the nation’s major human rights organizations, for help. Seeing opportunity to aid the educational pursuits of young people, Urban League officials sent inquiries to the presidents and leaders of historically black colleges in the South. One of the first people they contacted was John Hope, president of Morehouse College. An astute academician and politician, Hope was among the first to recognize that blacks were migrating away from Southern states. While traveling in New England in 1916, Hope saw first hand Southern African Americans working as “section men with pick and shovel” for Northern railroads. The New York, New Haven, and Hartford railroad lines each had a visible African American presence in their workforce.

While Hope would have preferred to have working-class African Americans remain in the South, he tossed the blame for the exodus into the political lap of Southern white leaders. He knew that most leading Southern white politicians remained silent on vigilante violence directed at innocent African Americans. In addition, landowners had no qualms about using guns to maintain sharecropping, the economic system that dominated the lives of most African Americans. Although people worked for a share of the crop to be used to offset yearly expenses, most sharecroppers found themselves sinking deep into debt, never receiving enough in compensation to rise to land ownership.

However, Hope’s immediate focus was on his students. He carefully oversaw the hiring of 25 young men for tobacco work. While these students labored in Connecticut tobacco fields, other Morehouse men toiled in summer jobs in the Midwest, other parts of New England, and Pennsylvania. Fellow college presidents from African American colleges and universities followed Hope’s lead. In pursuit of jobs, poor and working-class African Americans soon followed the wave of college students. [For more on Southern student tobacco workers in Connecticut, see “Laboring in the Shade,” Summer 2011.]

Migrants’ survival depended on their building relationships with people who were already knowledgeable about life in Connecticut. New Haven minister Rev. Edward Goin, concerned about the plight of new arrivals, organized to meet their needs by building a social center in a boxcar and enlisting African American students at Yale to provide support. Migrants adopting New Haven as their new home now had advocates from the city as part of their network.

Given the terror many dealt with daily in the South, Connecticut seemed like an oasis. In Southwest Georgia, for instance, an area from which large numbers of African Americans made the exodus to Connecticut, brutal lynchings were common. Some labor recruiters capitalized on this fear to lure workers northward.

Not all the blacks who moved to Connecticut were from the South. Black immigrants, primarily from the Caribbean islands, also came to urban areas such as New Haven and Hartford to work. The 1920 census lists the birthplaces of such immigrants as Jamaica, Bahamas, and the Virgin Islands. For other Caribbean immigrants, the census lists the immigrants simply as “West Indian.” The census also documents the presence of a small group of Puerto Ricans, some of whom may have been of African ancestry. Cape Verdeansfurther helped to increase Connecticut’s black population. Most of these immigrants found steady, though lowpaying, working-class positions, with occupations that in many cases were similar to those of African Americans from the South.

The family of Constance Baker Motley, the legendary civil rights attorney from New Haven, came from the island of Nevis. Her father immigrated to that city in 1906—a decade before the Great Migration. Motley’s mother followed a year later, paying the tidy sum of $25 for travel via a ship’s steerage-class fare. While her family resided in a mixed neighborhood of Caribbean people, Greeks, German Jews, and Italians, most African Americans in New Haven called the Dixwell Avenue area home.

Although World War I opened employment opportunities in some areas, African Americans from the South soon discovered what many local blacks already knew: Their race worked against them in the job market. While unskilled and skilled white immigrants found work at Winchester Repeating Arms Company, New Haven Clock Company, and New Haven Box Company, these places remained off limits to African American workers. Samuel Gompers and the American Federation of Labor loudly supported the rights of white skilled laborers but not those of African Americans working in any capacity. In Connecticut’s larger towns it was well known that law enforcement jobs “belonged” to Irish people and sanitation jobs to Italians. As Mary White Ovington noted in Half a Man (Hill and Wang, 1969), sanitation, gardening, and housekeeping fell to African Americans throughout the South, but not in Connecticut.

While Southern migrants clearly welcomed the job opportunities that tobacco growers and other companies offered, they eagerly searched for higher-paying work, often only making inroads in certain service occupations. But higher-paying jobs generally were available only to those with union connections— and unions often denied membership to African Americans. That denial ultimately benefited tobacco growers and companies that used non-union labor.

While World War I mobilization led to economic growth for the state as a whole, and the 1920s brought economic growth for the nation, African Americans saw limited economic opportunities in the period after the war. According to Charles S. Johnson, a leading sociologist of the period, African Americans found few opportunities in either skilled or unskilled work. His survey of Hartford, started in 1921, revealed that the majority of Hartford industries (60 percent of those surveyed) did not employ substantial numbers of African Americans. One heavyindustry company, Pratt and Cady, had 100 African American workers at the peak of the war; by 1923 that number had dwindled to 25, while white workers remained at the plant. When African Americans did find work, their duties tended to be extremely demanding physically, and the jobs often were seasonal. Hod-carrier duties, coal yard work, and lumber work areas are examples. Colt’s Patent Firearms Manufacturing Company, Hartford Machine Screw Company, Pratt & Whitney, Royal Typewriter Company, and Underwood Typewriter Company preferred to hire African Americans only to perform unskilled duties such as custodial work. The apprenticeship program at Pratt & Whitney included no African Americans during the war years. The huge insurance giants surveyed by Johnson were no better than heavy industry in this regard.

Inadequate housing was another perpetual problem for African Americans in urban areas. The influx of thousands of African Americans desperate to find housing gave slumlords ample opportunity to overcharge new arrivals from the South. As Johnson’s survey documents, slumlords overlooked poor plumbing, and city policies allowed large numbers of people to be packed into already overcrowded areas. New Haven’s Dixwell neighborhood and Hartford’s North End quickly became densely populated. As in larger urban areas, discriminatory local policies played a major role in creating and maintaining substandard housing.

Still, small numbers of African Americans became substantial property owners or found quality housing. The Hartford Courant reported (“The Colored People Who Live in Hartford,” October 24, 1915) that in 1915 a master mechanic at the Hartford Machine Screw Works owned both a house for his family and tenement houses in Hartford.

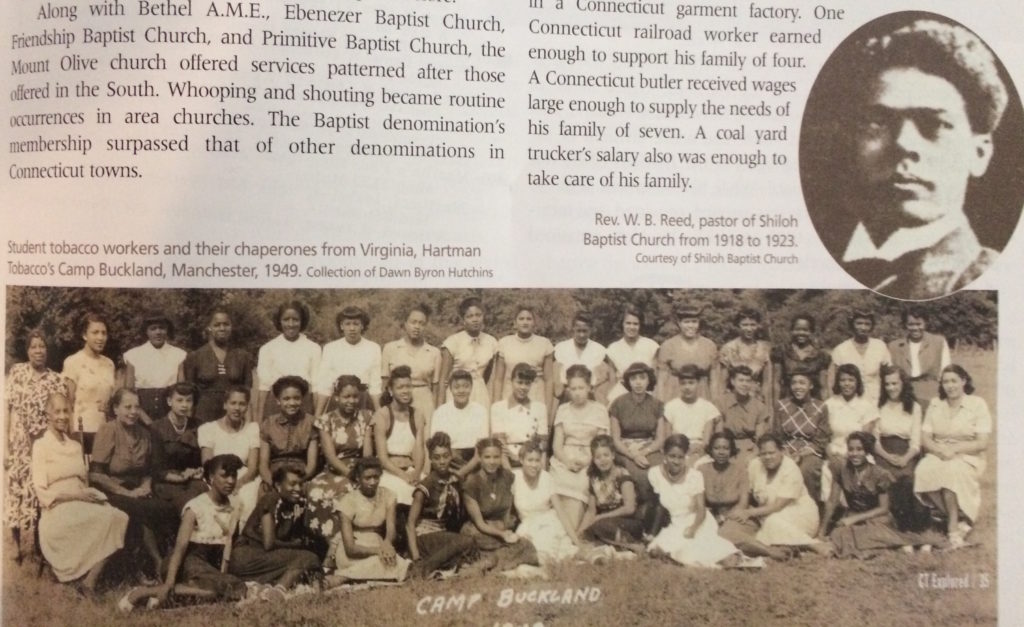

Rev. W. B. Reed, pastor of Shiloh Baptist Church, 1918 – 1923, courtesy of Shiloh Baptist Church and tobacco workers, courtesy of Dawn Byron Hutchins

The mass migration of Southern African Americans occurred around the same time that leadership among national African American leaders reached a turning point. W.E.B. Du Bois and other members of the Niagara Movement forged an integrated alliance with whitesthat became the National Association forthe Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). In 1917 Connecticut cities launched efforts to build NAACP chapters. New Haven citizens were the first in the state to organize; Hartford’s local NAACP initially drew its membership from among distinguished members of the African American and white communities, with 20 people meeting to organize at Mary T. Seymour’s New Britain Avenue home in 1917. On December 10, 1917, the national organization granted the Hartford branch’s charter.

Although key national figures such as DuBois, James Weldon Johnson, and Mary White Ovington visited and spoke to state branch members, local people carried out the organization’s daily business. Local members mounted a campaign to eradicate continued discrimination, inadequate housing, racism, and Southern lynching. Statewide membership came from an alliance of native-born African Americans, Southern migrants, and local white supporters. One of the major efforts of the war period was a campaign by Connecticut NAACP members to push the state assembly to pass a civil rights act.

While the NAACP’s actions produced some benefits, the migration of thousands of African Americans to Hartford caused class conflict and tension between Connecticut-born African Americans and African American migrants from the South. Alabama native and author Rev. W.B. Reed, pastor of Shiloh Baptist Church, a well-established congregation on Albany Avenue in Hartford, criticized Southern-born migrants for organizing independent churches, separate from those attended by African Americans born in Connecticut. Reverend Goode Clark, an ordained pastor from Americus, Georgia, followed his members to Hartford. Clark had drawn Reed’s ire in 1919 by organizing Mount Olive Baptist Church two years before.

Along with Bethel A.M.E., Ebenezer Baptist Church, Friendship Baptist Church, and Primitive Baptist Church, the Mount Olive church offered services patterned after those offered in the South. Whooping and shouting became routine occurrences in area churches. The Baptist denomination’s membership surpassed that of other denominations in Connecticut towns.

African American churches accorded dignity and respect to people whom mainstream society often dismissed. Domestics, gardeners, tobacco plantation laborers, hod carriers, and others received respect assisters or brothers of the faith in their churches. Some of these members served as deacons, pastors, elders, bishops, or missionaries. Members understood that the church was the one place in which all were equal in the eyes of their God.

Elsewhere, Connecticut lacked true social freedom. White theater owners, for instance, regularly segregated African Americans in the galleries. In 1927, when blacks decided to seek legal redress to end discrimination by the State Theater, they turned to attorney Thomas J. Spellacy to take the case. Owners of Hartford’s Observer, a local African American paper, led the charge against the theater. Eventually, the theater opened seating to all.

With the war over, some African American working-class families, even those who needed at least two breadwinners, managed to find small pockets of opportunities. Among typical examples of working-class families documented in the 1920 census, the father in one family of eight worked in the coal yards, while a daughter toiled in a local store. An elevator operator went off to work daily at an insurance company, while his spouse worked for a tobacco firm. While her husband spent his days in a machine shop, one woman worked in a Connecticut garment factory. One Connecticut railroad worker earned enough to support his family of four. A Connecticut butler received wages large enough to supply the needs of his family of seven. A coal yard trucker’s salary also was enough to take care of his family.

In the 1920s, the urbanization and clustering of African Americans in Connecticut allowed for the growth and development of African American businesses and political power. Grocers catering to Southern foodways, barbers, painting companies, dress-making shops, beauty salons, restaurants, saloons, and pool halls dotted the Connecticut landscape. African American physicians and attorneys conducted business in most major Connecticut cities.

The 1920s ushered in the age of jazz. The music roared into Connecticut’s African American community as it did elsewhere. One of the most prominent local jazz artists in Hartford was Bessye Fleming Profitt. As noted in Diana Ross McCain’s Black Women of Connecticut: Achievement Against the Odds (Connecticut Historical Society, 1984), the Atlanta native was a contemporary of Count Basie, Lionel Hampton, and Sophie Tucker. Profitt’s first move to New England was not to Hartford, but to Willimantic, where she married a local man. In 1921 she moved to Hartford and gained a solid local following.

For African Americans, the Roaring Twenties was also a time of leadership battles. The Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) formed in 1914 in Jamaica; its founder Marcus Garvey thought W.E.B. Du Bois’s notion of integration was detrimental to African Americans and that white racism would never change. Garvey, through UNIA, demanded respect and urged black people to build their own government and large-scale businesses. His message of uplift caught the attention of millions of black people across the world.

By 1922 Connecticut had several UNIA divisions with large memberships, including one in Hartford. Other areas of Connecticut, including New Haven, New Britain, Portland, East Granby, and Rockville, had visible and active divisions of the UNIA. One of the great highlights of the Hartford UNIA was Garvey’s 1924 visit to Hartford. While his movement began to decline significantly after he was arrested, convicted, and incarcerated for mail fraud (1925 to 1927), his ideas remained ingrained in the memories of Connecticut members. (In 1927 the U.S. government released an ailing Garvey and deported him back to Jamaica.)

The 1929 stock market crash was followed by a decade-long economic depression that battered poor and working-class people throughout the state. For African Americans, surviving the “Old Hoover Days” often meant living in fear, going on relief, receiving church aid, being uplifted by ministers’ sacrifices, and embracing New Deal programs. The election of Democrat Franklin Roosevelt brought fear and dread to the hearts of many African Americans in Connecticut. The Democratic Party’s ties to Reconstruction and the Jim Crow South caused many to view it as supportive of terror policies and discrimination against African Americans.

African American churches opened soup kitchens and cooperatives to aid the community. Hartford’s Rev. Robert Moody and Shiloh Baptist Church provided food, clothing, and firewood for the needy. Rev. John Jackson, pastor of Hartford’s Union Baptist Church and a native of South Carolina,simply decided not to take a salary during the height of the Great Depression.

African American churches opened soup kitchens and cooperatives to aid the community. Hartford’s Rev. Robert Moody and Shiloh Baptist Church provided food, clothing, and firewood for the needy. Rev. John Jackson, pastor of Hartford’s Union Baptist Church and a native of South Carolina,simply decided not to take a salary during the height of the Great Depression.

Although times were difficult, the turbulent 1930s failed to totally derail small African-American-owned businesses. Business owners usually located themselvesin the heart of the African American community. Aware of cultural needs and wants, African American grocers sold staples of the Southern African American diet such as black-eyed peas, “side meat,” chicken, Argo starch, and vegetables. In addition, African American women operated salons where they pressed hair and provided nail care.

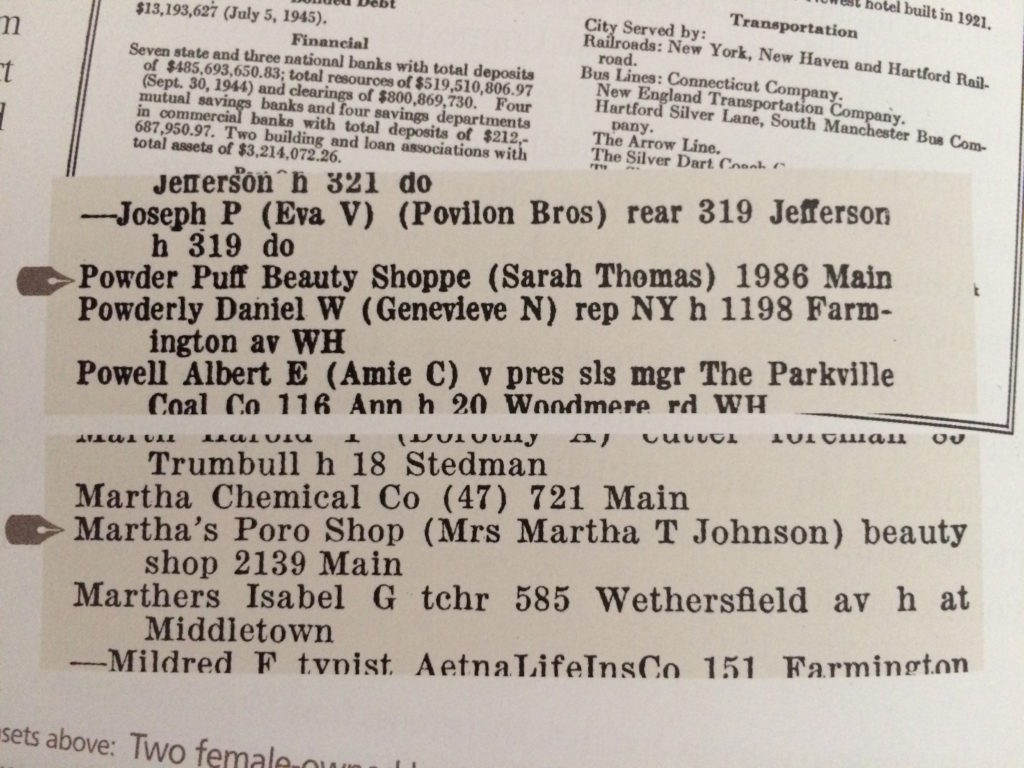

Hartford City Directory listings for female-owned African American businesses in Hartford, 1930 and 1940

In Hartford, the owners of Richardson’s Beauty Shop, Martha’s Poro Shop, and Powder Puff Beauty Shoppe were African American, and they provided important social, psychological, and economic benefits to their African American clients. For African American women, who were often ridiculed for their looks and features, a salon visit both affirmed their sense of their own beauty and strengthened their social network. In salons, women vividly and openly discussed community news, just as African American men did in barbershops throughout Connecticut. Because the owners owed their livelihood to African American customers and patrons, not the white establishment, those customers felt free to express their political views. In addition to these black-owned hair-care facilities, cities such as New Haven, Hartford, and Bridgeport had a small and respected contingent of dentists and physicians of African descent. Throughout Connecticut, African American undertakers conducted solid business enterprisesin embalming and burials. In hair care, medicine, and undertaking, African Americans typically chose to deliberately patronize African American merchants.

Connecticut’s African American population of this period believed in keeping itself economically and politically aware. In 1938 African Americans from throughout the state attended the Connecticut Negro and Occupational Conference. John E. Rogers set the tone by articulating the beliefs of African American attendees, arguing that although whites had long held paternalistic attitudes toward African Americans, increased education would empower African Americans to look after their own affairs.

As the 1930s drew to a close, Connecticut’s African American community huddled primarily in the state’s largest cities, clustering together for strength and survival. Rev. John Jackson met with Governor Raymond Baldwin to highlight the lack of economic opportunity for Connecticut’s African American workers, and demanded that the governor provide better treatment of African Americans in the state. As a result, African Americans received appointments working at state tollbooths and in clerical positions.

(l-r) Rabbi Morris Silverman, chair of Connecticut’s Inter-Racial Commission, Dr. John C. Jackson, member, and Hartford Public Library librarian Magnus Kristofferson, February 25, 1950. The Hartford Times, Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Greater changes would come in the 1940s, and in the process, Jackson and indeed all African Americans in the state would feel the brunt of Southern injustice and bring the civil rights crusade home to Connecticut. Connecticut of the 1940s had a hand in shaping the ideas of a young Martin Luther King, Jr. During the summer of 1944, King, as a young Morehouse College student working on a Simsbury tobacco farm, experienced life in a non-segregated society for the first time. In My Life with Martin Luther King, Jr., Coretta Scott King recalled that her eventual husband experienced an incredible sense of “freedom” while in Connecticut. She argued that the opportunity to lead devotional services with other students that summer started King on the road to becoming a minister. Later efforts by Connecticans working closely with King, one of the world’s greatest human rights ambassadors and breakers of racial barriers, would make important contributions to the non-violent civil rights movement he led in the South.

Explore!

Read more about African Americans in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.