(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2006-2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Upon receiving financier J.P. Morgan’s 1917 gift of his father’s collection of 1,600 European decorative art objects to the Wadsworth Atheneum, a gift that would help fill the cavernous new galleries of the recently opened Morgan Memorial wing, the museum’s trustees hired the institution’s first professional to take charge of the now-substantial gallery and collection.

In a highly unusual move for the times, and from a national field of candidates, they hired a woman: Florence Paull Berger.

The exploits of legendary Atheneum director Chick Austin, the flamboyant champion of modernism and the avante garde whom Berger both preceded and succeeded, have long overshadowed her considerable contributions. Berger was a 20-year veteran of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston when she arrived at the Atheneum in 1918. It was she who transformed the Atheneum’s art holdings from a hodgepodge of collections of varying quality into a modern-day art museum.

To appreciate how different the institution Berger encountered in 1918 was from that of today, one need look no further than the word “Atheneum” in its name. For its first 100 years, the Atheneum was truly an atheneum—more library than art museum. Along with Daniel Wadsworth’s picture gallery, it housed the Watkinson Library (now at Trinity College), the Hartford Public Library, and the Connecticut Historical Society until well into the mid-20th century.

Berger wasn’t the first woman to influence the Atheneum’s transformation into an art museum. In the late 1880s, a group of illustrious and ambitious women led by gun-maker Elizabeth Colt paid to repair a leaky skylight in the original 1842 Atheneum building. In 1886, they also reopened the gallery—which the trustees had closed two years earlier because nobody bothered to visit—to the public. In exchange for their largesse, these women of the Art Society of Hartford convinced the trustees to let them use the gallery for their fledgling art school (later to become the Hartford Art School at the University of Hartford). [See An Art School Forged in the Gilded Age, HRJ Summer 2003.]

The re-opened gallery was an instant success, drawing regular crowds, and the Art Society’s efforts showed the trustees that the exhibition of art had potential. For its trouble, though, the society was kicked out of the gallery three years later for, under the firm guidance of Reverend Francis Goodwin, the Atheneum’s president, and the generous financing of Goodwin’s uncle Junius Spencer Morgan and his family, big changes were afoot. Over the next 25 years, the Morgan family—father, son, and grandson—poured nearly $1 million into the museum, erecting a wing in its own name that more than doubled the Atheneum’s size. Connecting the original Atheneum building and the Morgan Memorial was the Colt Memorial, funded with a $50,000 gift by bequest of Elizabeth Colt, who died in 1905. But still, even by the time of Berger’s arrival, the Atheneum could not properly be called an art museum, for its art collection was largely a dusty, uneven accumulation of old stuff.

As the Atheneum struggled with its identity, Florence Paull Berger found herself hitting a glass ceiling at Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts. A young, single, working woman from Albany, New York with no significant family connections and no college education, she started out as assistant to museum director Charles G. Loring in 1896 and proved to be a quick study. She was appointed assistant registrar after helping to perfect and put into practice the system of inventorying museum objects that became the standard for museums until the advent of computerized systems. She was later put in charge of the American and European decorative arts collections and was sent to Europe in 1905, 1908, 1910, and 1914 to study art and museums abroad. The purpose of the 1908 trip was to study how other museums displayed their collections in preparation for installing the galleries of Western art in the new Museum of Fine Arts building on Huntington Avenue that opened the following year. On this trip, she viewed more than 100 galleries and collections.

While at the MFA, however, she was also deeply involved in the exploding interest in America’s own decorative arts as the Colonial Revival gained momentum. Collecting antiques was becoming fashionable, a trend that would reach its apex in the 1920s. As a museum curator, Berger was at the forefront of the national movement, bringing objects from relatively new private collections into public view in the galleries of the MFA. Involved in several of the earliest exhibitions of American decorative arts in this country, she played a pivotal role in “canonizing” these objects as worthy of inclusion in America’s art museums.

Florence Berger and her husband, Boston Symphony Violinist Henri Berger, date and location unknown. Wadsworth Atheneum Archives

By 1918, with her work under-appreciated by the MFA’s trustees, a war on, and a major influenza epidemic closing down public buildings all over the Northeast, Berger was ready to make a move. Likely through her contacts in the antiques collecting world, she was offered a position with great potential at the Wadsworth Atheneum. With the title of general curator, a title she had been denied at the MFA, she was charged with taking the raw materials of the Atheneum’s collections, housed in the Morgan and Colt buildings, and transforming the gallery into a full-fledged art museum. But before leaving Boston, at the age of 47, she married Henri Berger (he was 52), a French-born violinist for the Boston Symphony, beginning what may be one of the earliest long-distance marriages on modern record. (Three years later, after a 31-year career with the Boston Symphony, Henri moved to Hartford and joined the faculty of the Hartt School and Hartford School of Music.)

Berger arrived in June 1918 to a museum that had, once again, been closed for months. She reported to the Atheneum’s first director Frank Gay, the librarian of the Watkinson Library, who oversaw all the Atheneum’s tenants. Berger found a painting collection that filled only two galleries; the other 18 were dominated by Morgan’s collection of European decorative arts, including bronze sculpture, pottery, porcelain, ivory, enamel, and silver.

top: Wadsworth Atheneum showing the building funded by Elizabeth Colt’s bequest (center), and the Morgan Memorial (right) which opened to the public in stages from 1910 to 1913. middle: Morgan Great Hall, Wadsworth Atheneum, 1924, as reinstalled by curator Florence Berger. bottom: The George Dudley Seymour furniture collection in the Atheneum’s Morgan Memorial in the 1920s. The bulk of Seymour’s collection went to the Connecticut Historical Society after Seymour’s death, except the corner cupboard which remains in the Atheneum’s collection. Wadsworth Atheneum Archives

What Berger did over the next 33 years would make any 21st-century museum trustee proud. Never simply a curator, Berger was a cultural entrepreneur. She instituted a regular series of changing exhibitions and public programs, inventoried the collection for the first time in the Atheneum’s 75-year history (a task that took 5 years and the assistance of another longtime, loyal, and female employee, Marjorie Ellis), solicited loans and gifts to fill major gaps in the collection and galleries, reinstalled the entire first floor of the Morgan Memorial, launched the museum’s first membership program, and instituted the museum’s first members’ bulletin. Berger transformed what had been in large part a static repository of objects to an active and lively place with a strong educational mission. On top of all that, she balanced the budget.

Perhaps most importantly, she brought a keen and educated eye to her curatorial duties. Berger instituted a higher standard of connoisseurship than the Atheneum had previously applied, initially causing some internal grumbling. When she introduced the idea that an exhibition would not be a broad compendium of objects but would be edited for quality, though, colleagues in the museum world responded enthusiastically to the marked improvement in the gallery installations.

Armed only with a typewriter, carbon paper, index cards, and her wits, Berger organized a dizzying array of exhibitions. Because museums simply did not have the comprehensive collections they do today, Berger mined her extensive network of private collectors for each show, often borrowing objects from 50 lenders or more.

Berger often collaborated with groups—and frequently these were women’s organizations. Her very first special exhibition was a textiles show, organized with the aid of the Art Society of Hartford, on whose board of managers she later served. Costumes and textiles became a major interest of Berger’s, and with this exhibition, she launched the Atheneum’s costume and textiles collection and the museum’s first special purchase fund, amassed largely by female donors. Years later, in semi-retirement in the 1950s, Berger would serve as the museum’s first curator of costume and textiles.

Among Berger’s earliest exhibitions was one that featured the collection of Connecticut’s insurance commissioner, Burton Mansfield of New Haven. Reputed to be the finest private collection in the state, it featured late 19th-century American paintings by James MacNeil Whistler, John Singer Sargent, Henry Ward Ranger, and Winslow Homer, along with works by Connecticut Impressionists John Twachtman, Willard Metcalf, J. Alden Weir, and Childe Hassam. Also on view from Mansfield’s collection was Persian pottery and glass from 800 A.D. to the 14th century.

Even as Berger mounted such shows as the Mansfield collection, which represented her more traditional exhibition leanings, she organized a far less traditional exhibition of handcrafts from 18 nationalities titled Native Arts of our New Americans in collaboration with the Daughters of the American Revolution. By 1920, only an estimated 29 per cent of Hartford’s residents were native-born whites. The city was bustling with immigrants, and Berger sought to open the Atheneum’s doors to Hartford’s residents. The theme of “Americanizing” these immigrants by assimilating them to “our” ways was then a prevalent concern of Hartford’s—and the nation’s— ruling class. This impulse to preserve American culture (as defined largely by persons of Anglo Saxon descent) had fueled the Colonial Revival since the late 1800s. The exhibition and an accompanying pageant drew capacity crowds.

A pageant staged at the Wadsworth Atheneum in 1920 to accompany the exhibition “Native Arts of our New Americans.” Though seemingly celebrating the immigrant cultures of Hartford’s newest residents, the subtext was Americanization. Wadsworth Atheneum Archives

Berger also created closer connections with the antiques-collecting movement and thereby continued to raise the Atheneum’s profile. For her first American decorative arts exhibition, The Early Plate in Connecticut Churches Prior to 1850, she recruited the Colonial Dames to canvas churches for loans of their church silver. Of the exhibition, Atheneum director Frank Gay remarked, “Probably nothing we have ever done has made the Museum so well known through the State.”

Although Berger’s tastes were largely conservative and consistent with the museum’s customary ban on showing the work of living artists, Berger organized an exhibition of modern American paintings loaned by nine New York art dealers. Although far from cutting edge, this exhibition, coming a decade after the famous 1913 New York Armory Show, marked the first time the French Impressionists were shown at the Atheneum. Berger secured loans of works by Pissarro, Sisley, and Monet from the famous New York dealer Durand-Ruel.

In an article she wrote for The Hartford Courant, Berger remarked, “Still, when Monet, Sisley, Pissarro and the other so-called Impressionists, whose work now looks so sane and moderate to us, first exhibited in Paris, it was spoken of as a ‘tragedy’ that such pictures should be shown and called ‘art.’… But the last ten or fifteen years have produced infinitely greater horrors in paint on canvas than these men have ever imagined.” Still, of her next exhibition, a watercolor and drawing show with works by Cezanne, Mary Cassatt, Cecelia Beaux, and John Marin, The New York Tribune remarked, “We wish the loan exhibition … being held in the Museum in Hartford might be seen here. … It has an uncommonly interesting range. … That is the kind of courageous diversity that makes a show entertaining.”

After years of such successes, Berger’s singular reign over the Atheneum’s art museum began to erode in 1924. The precipitating event was the death of Hartford banker Frank C. Sumner, who left more than $1 million to the Atheneum for the acquisition of paintings to be realized by the museum upon the death of his wife (the bequest would be realized just three years later). The museum suddenly found itself in an entirely new position: it had money to purchase works of art. A lot of money. Berger had been hamstrung by miniscule funds, but this bequest promised that the dreary days of relying on the fickle whims of donors to make gifts to the collection of questionable quality were over.

With an earlier bequest by art dealer and trustee Samuel Avery for a building addition, the trustees found themselves with the resources to take the museum to another level. The focus of the Atheneum shifted away from its tenant organizations and toward creating a world-class art museum.

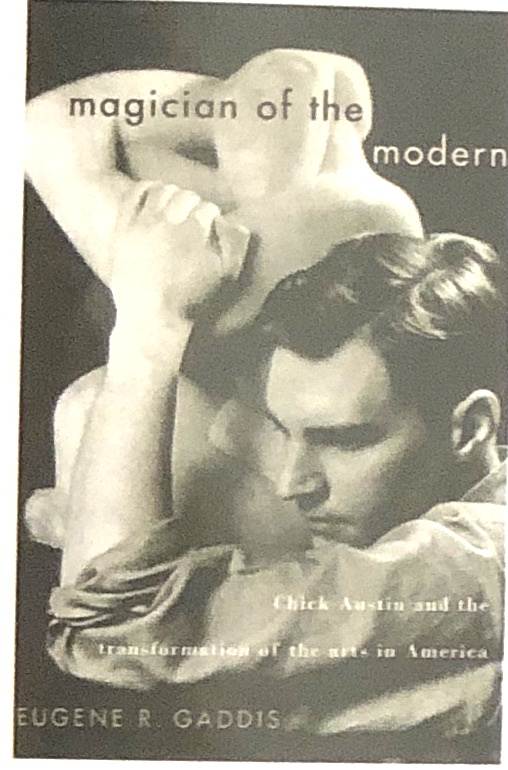

Chick Austin, shown here on the cover of Eugene Gaddis’s biography Magician of the Modern: Chick Austin and the Transformation of the Arts in American (Random House, 2000), brought modern art to Hartford as the director of the Atheneum, building on the foundation laid by general curator Florence Berger.

These heady prospects before them, the trustees brought in a new director over Berger’s head. Having inherited his post from his father, Atheneum president Charles Goodwin sought advice from an old acquaintance, Edward Forbes, director of the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University. Forbes hand-picked 26-year-old, Harvard-trained Arthur Everett “Chick” Austin, Jr. for the job. Thirty years younger than Berger, Austin, an aesthete—with top-notch academic credentials and the social network to match—was the polar opposite of the pragmatic, pulled-up-by-her-bootstraps Berger.

While perhaps Berger’s most influential period came to a close with Austin’s hiring, she persevered, achieving the position of acting director for a three-year period, 1943 to 1946, after Austin, whose championship of the modern ultimately proved too much for the trustees, departed. She continued as general curator until 1951, just shy of her 80th birthday. She produced several important exhibitions later in her career, including The Nude in Art and This Was Hartford: Victorian Silks and Settings, both in 1946. In 1951 the Atheneum honored Berger upon her retirement with a gala event attended by museum dignitaries from around the world. Jacques Dupont, Inspecteur General des Monuments Historiques de France, and Fillippo Magi of the Vatican attended from abroad. Museum directors from across the U.S. attended, including Henry Francis Taylor of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Adelyn Breeskin of the Baltimore Museum of Art, and Dr. Esther I. Seaver of the Dayton Art Institute—the latter two of the earliest women to attain the title of director.

Florence Paull Berger at her desk at the Wadsworth Atheneum, 1940. She retired as general curator in 1951 at age 80, and became the Atheneum’s first curator of costumes and textiles. Berger died in 1967, just shy of her 96th birthday. Wadsworth Atheneum Archives.

Berger’s tenure aside, the Atheneum has been slow to allow women to attain high rank. It wasn’t until 1955, for instance, that women were appointed to the Atheneum’s board of trustees—and even then, the first appointees were the current and immediate past presidents of the museum’s Women’s Committee, rewarded for their volunteer work with a seat at the board table but assigned to the House Committee, far from the power centers of finance and curatorial matters. (By contrast, women had served on the board of the Philadelphia Museum of Art since 1915 and were founders of the Museum of Modern Art and the Whitney Museum of Art in the 1920s.) It was another 40-odd years before the first female president, Nancy Grover, was elected in the late 1990s, and the museum’s first female director, Kate Sellers, wasn’t hired until late 2000.

Berger was among the first generation of professional curators of either gender. Had she been among the next generation, she may have attained a full directorship. Her successor as general curator, Dr. Evan Turner, left the Atheneum to become the director of the Philadelphia Museum of Art and later the Cleveland Museum of Art. Despite the glass ceilings she encountered at both the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston and the Wadsworth Atheneum, over the course of a museum career that spanned 55 years, she contributed mightily to defining both what it meant to be a curator and what it mean to be an art museum in America. At the time of Berger’s death, The Hartford Courant acknowledged her tremendous contribution, “Bringing the Wadsworth into its first line maturity as one of the great art institutions of the country was Mrs. Berger’s great contribution.”

Elizabeth Normen is publisher of Connecticut Explored. The story is based on her final project for her MA in American Studies at Trinity College.

Explore!

“An Art School Forged in the Gilded Age: The Hartford Art School”, Summer 2003

Read more stories about Connecticut’s Art History on our TOPICS pages.