By Henry S. Cohn

(c) Connecticut Explored Winter 2017-2018

In the 1630s the Connecticut colony had little precedent for addressing the issue of divorce. England granted divorce in its ecclesiastical courts as a religious matter. Marriage for the Puritans was a civil—not religious—matter. Ministers could not perform marriages in Connecticut until British law was imposed on the colony under the Dominion of New England in 1686. As a result Connecticut initially developed a divorce mechanism that differed entirely from English practice. The Connecticut position, liberal for its time, also broke with most other colonies (and later most states) that relied on the Bible’s Matthew 19:7 to guide its divorce laws. Matthew 19:7 famously says that what God has joined together, no man may put asunder.

What was behind the Connecticut colony’s approach to divorce? The settlers of Connecticut considered preservation of the family unit part of their social policy. Unrestrained family disruptions had to be kept to a minimum. The colonial leaders were determined to adopt a progressive approach to divorce and find a place for this action in civil society as a means of eliminating community strife. At the same time, these officials required that divorce occur under strict controls, with court review of proof and fault. Through this, not only did Connecticut throw off the shackles of the English ecclesiastical court, it also chose to avoid the complete bar to divorce that stood in some colonies and the total lack of control over the husband and wife in other colonies.

In the towns of Windsor, Hartford, and Wethersfield (which made up the early colony of Connecticut) divorces were first granted solely by the general court. This body possessed the legislative power and much of the judicial power of the community. (Those powers were separated later on.) At the general court evidence for the divorce (by deposition, in large measure) would be collected. The members of the general court would then consider the case and reach a decision. The hearings were highly informal. There were no set procedure or enumerated grounds. And often there was an attempt made to avoid the divorce by attempting to reconcile the parties.

While taking place before a primarily legislative body, these early divorces had judicial aspects. They were not the same as the legislative divorces of other colonies, which involved the passing of a special act of divorcement. Justice William Hamersley (writing in 1905) has termed the Connecticut colony’s divorces as ‟judicial” in form and lacking in the elements of legislative divorce. He gives as an example the general court’s use of local magistrates to take evidence before the divorce was allowed. In the earliest recorded divorce case—that of Goody Beckwith in 1655—Goody presented to the general court evidence of her husband’s ‟departure and discontinuance.” The court decided that she must then testify further to magistrates at ‟Strattford.” The magistrates would then be empowered to issue a bill of divorce.

The colony of New Haven also developed a divorce mechanism during this period. (See Jon Blue, The Case of the Piglet’s Paternity, 2015.) The Laws of New Haven of 1655 include an article devoted to divorce. The court of magistrates (the lowest of the local courts) was to be the exclusive body for the granting of divorces. Divorce was to be granted ‟upon complaint, proof, and prosecution” showing that the spouse had committed adultery and fled punishment, or that the husband had failed in his conjugal duties to the wife, or that one spouse had willfully deserted the other, refusing all matrimonial society. The statute cites Bible verses Matthew 19:9 and I Corinthians 7:15 in support of its provisions. In 1663 the ground of seven years’ absence was added by the New Haven General Court, the members of the legislature finding ‟the law for divorce already provided and in force, to be short in some cases. . . .”

It is to be noted that the New Haven colony’s law of divorce tended more toward present practice than did that of the colony of Connecticut. After the two colonies merged in 1665 and the establishment of the court of assistants in 1666, the Connecticut General Assembly in 1667 decreed that the court of assistants would hear certain divorce cases. The court of assistants was renamed the ‟superior court” in 1711. The court of assistants (hereinafter the superior court) was to grant divorces on certain grounds: adultery, desertion, fraudulent contract, and seven years’ absence (much like the New Haven laws of 1655.) When a party had one of these specified grounds to claim, he or she went to the county superior court. When that lower court couldn’t find sufficient grounds to grant the divorce, the case went to the Connecticut General Assembly as it still was the body of original jurisdiction. The Connecticut Superior Court also referred difficult petitions to the general assembly, requesting guidance as to what their legal options were.

Though more liberal than in other places, divorce in Connecticut was still a complicated matter. A good example is the 1713 case of John Merriman against his wife, Hannah. In 1713 Hannah deserted John, leaving Wallingford and going to live with her relatives in Windsor. John, almost at once, sought relief through the general assembly but was refused. He also was refused while seeking divorce in the Hartford Superior Court because his allegations were not proven. Meanwhile John wrote reconciliation letters to his wife, saving a witnessed copy of each for his records. He also collected sworn statements from Windsor citizens that he had asked his wife to return. John tried again, this time in New Haven. He tendered his ‟accusation” to the New Haven Superior Court in September 1716 on the grounds of three years’ willful desertion.

Hannah was notified in Windsor of the complaint, and she answered and submitted a list of grievances. She said that ‟John Merriman has broken the most if not all the essential articles in his covenant of marriage with me.”

The trial took place in March 1717, with both parties testifying before judges John Hamlin, Samuel Eells, and Jonathan Law. John Merriman’s depositions were presented. The deponents included his sons, his servants, and his friends. His niece swore in writing that her uncle ‟lived in a kind of slavish fear of her [his wife].” John finally introduced into evidence a copy of an unrelated 1683 judgment of divorce in the court of assistants where the grounds had been willful desertion, as proof that he had legal grounds for the divorce.

Hannah had little to present. She testified that ‟she had rather be obliged to live in the jail all her days than to be obliged to live with her husband.” She tried to justify her strong dislike for her husband and pleaded for her position. Her daughters also took her side and told of John’s cruel mistreatment.

John then asked the court to call in the ministers of the churches of Hartford and New Haven to consider the ground of willful desertion from a religious vantage point. The use of divines—or ministers—to assist the court was common during this period. On July 17, 1717 the divines answered, approving of divorce in the case of a wife’s desertion. The Reverend Joseph Mose stated for the divines that while Jesus had disapproved of divorce, His opposition was solely based on overly liberal Old Testament law (Deuteronomy Chapter 24:1); the civil authorities of Connecticut could grant divorces for desertion and not violate Jesus’ limited animosity. Mose’s letter concluded: ‟And it is supposed in the letter and question that the husband be not so to blame, as may justify such separation.” Later in 1717 the court found that John was partially at fault and therefore refused his divorce.

John then appealed his case to the general assembly again—the body of last resort at this time. He stated that the superior court erred in failing to grant him a divorce because while he had proved the ground of desertion, Hannah had lied about his alleged cruelty. In May 1718 a bill was prepared giving John the right to a rehearing in the New Haven Superior Court. The bill passed both lower and upper houses after discussion. Notice was given to the superior court to reconsider the case in the court’s fall term. This hearing was held in October1718 in Hartford. Even though Hannah was not present, the divorce was finally granted by the court.

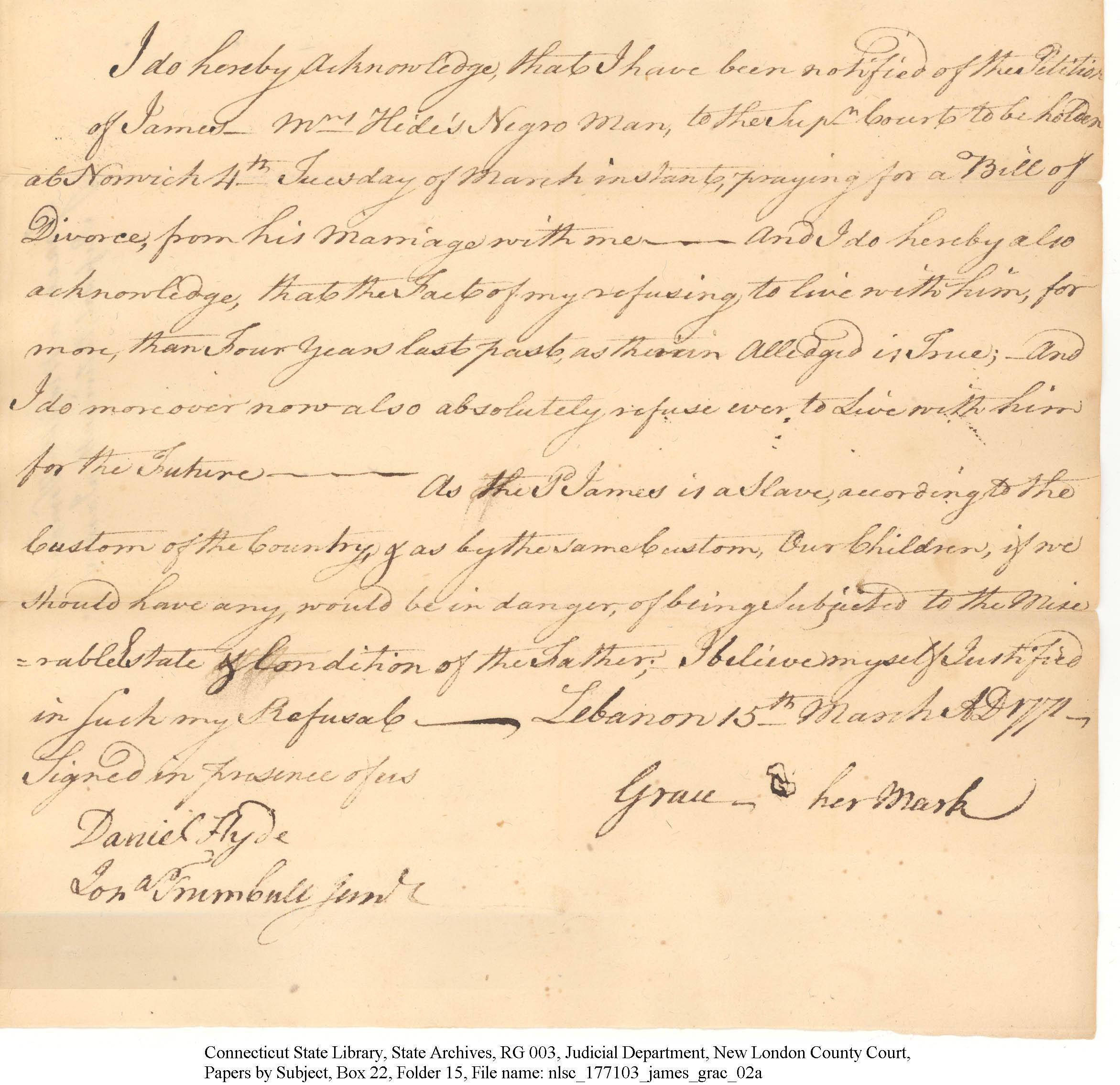

In what may be, according to the Connecticut State Archives, the earliest divorce case in the state involving African Americans, in 1771 James, an enslaved man owned by Abigail Hide of Norwich, petitioned the state legislature for divorce from his wife Grace on the grounds of abandonment. Grace was a free woman. She worked for Gov. Jonathan Trumbull in Lebanon. This is her deposition. She feared any children resulting from the marriage would be enslaved. The petition for divorce was granted.

There were those in the general community who were displeased by the liberality of Connecticut’s divorce procedures. In 1788 Benjamin Trumbull, a Congregational minister, published An Appeal to the Public, Especially to the Learned, with Respect to the Unlawfulness of Divorces. He charged that 390 couples had been divorced in Connecticut in the preceding half century and called for a change. When Bostonian Sara Knight traveled to New Haven in 1704, she reported in a diary and subsequent travel article that divorces ‟are too much in vogue among the English in this Indulgent Colony as their Records plentifully prove.”

Coming to the rescue was Zephaniah Swift, a lawyer and later Connecticut’s chief justice, who wrote a defense of divorce in his System of the Laws of the State of Connecticut (1795):

In this state the legislature has wisely steered between the two extremes. We neither admit that marriage is indissoluble, so as to involve a person in wretchedness for life, who is unfortunate in forming a matrimonial connection; nor do we allow it to be dissolved upon such slight pretenses, as give the parties the power of releasing themselves from it, when whim, caprice, or a relish for variety shall dictate. Substantial reasons only, which shew that the design of marriage is defeated, will have influence, and the validity of these reasons must be judged of by a court of law, and not by the party themselves. . . . The wisdom and good policy of this law, is evidenced by the consideration that in no country, is a greater share of domestic felicity enjoyed, than in this state.

No legal writer had greater influence on Connecticut law than Swift in 1795—and even into the 21st century.

In 1796 and 1797, under the direction of Elizur Goodrich, the general assembly reformed the divorce laws of the state. A new statute added a concrete requirement of notice with the possibility of postponement in any case in which the judge deemed it advisable. A three-year residency requirement was also added; presently it is one year.

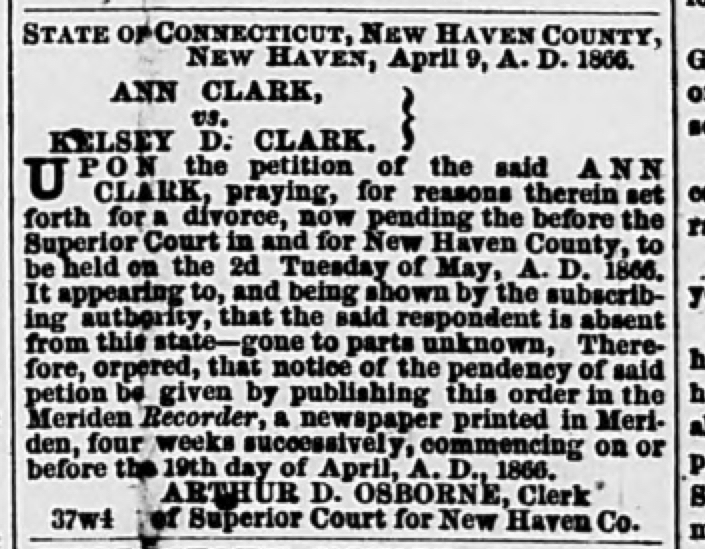

Meriden Recorder, May 9, 1866. The clear of the Superior Court for New Haven County placed this official notice four weeks running in advance of Ann Clark’s May court date.

After the Civil War, the divorce rate began to rise considerably, as Glenda Riley notes in Divorce, an American Tradition (Oxford University Press, 1991).While the increase was somewhat attributable to the war itself (as after World War I and World War II), the rate also grew throughout the later 1800s due to the increasing use of the action by the working classes of society. Dislike of divorce procedure grew in Connecticut even as the trend toward divorce continued.

In 1867 a bill was proposed, but not adopted, that would have provided for tighter controls on divorce. Among the bill’s provisions were: the requirement of two witnesses at ‟default” divorce hearings; all hearings were to be in open court, including committee hearings; a one-year waiting period before divorce would be granted on certain grounds; a six-month interlocutory period; and an optional provision to prevent the remarriage of the parties.

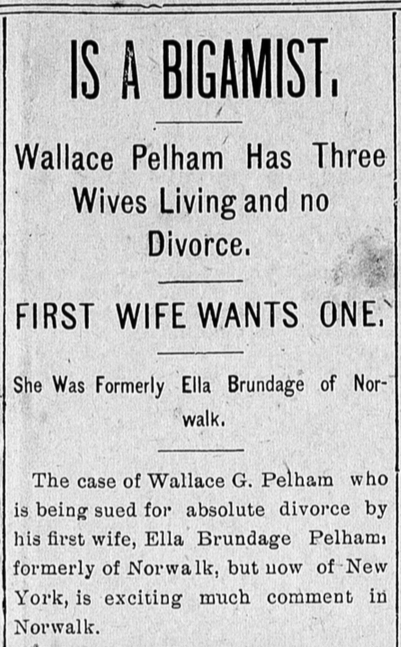

In 1868 Dwight Loomis, a Connecticut legal historian, felt grounds for divorce needed tightening, charging in the New Englander that, “By the operation of our divorce laws, bigamy and polygamy have been erected into an institution which retains all their vicious attractiveness, and without some of the restraints which in Oriental communities [presumably those that had harams]mitigate the practical operation of the system.” And in 1883 Dr. Morgan Dix, the rector of Hartford’s Trinity College, heavily criticized the allowance of divorce, stating that the action led to a breakup of the family and ultimately to what was feared most of all, Communism.

The Connecticut legal community’s reaction was once again one of moderation. After 1879 quicker procedures developed first to the growing number of cases where there was no appearance or answer by the respondent, and then in those cases where the parties stipulated for early determination.

The Hartford Courant was quick to respond to the anti-divorce movement. Its owners were Joseph Roswell Hawley and his best friend from Hamilton College, Charles Dudley Warner. Hawley, who wrote the newspaper’s editorials, was a cousin by marriage to Harriet Beecher Stowe and Isabella Beecher Hooker. He had been a law partner with Isabella Hooker’s husband John until the pull of the Civil War and post-war politics led him to give up his law practice. He shared the liberal Protestant values of the Hartford literary community. His July 23, 1881 editorial defended the status of divorce in Connecticut. It quoted from Swift’s System, in which Swift approved of divorce “when it is evident that the parties cannot derive from [marriage]the benefits for which it was instituted, and when instead of being a source of the highest pleasure and most enduring felicity, it becomes the source of the deepest woe and misery.” Hawley concluded: “That [Swift’s] statement is true and of fundamental importance is overlooked by many intelligent and respectable people, who being fortunate and happy in their own married relations, look upon divorce as an unmixed evil, and in the statistics of increasing divorce find proof that the world is growing worse.”

Hawley’s strong support for divorce carried the day, and the action survived. Court procedure became more refined over the years, eventually developing into the present system of uncontested or “no-fault” divorce. The ground ‟irretrievable breakdown” was added in the early 1970s. More recently, non-adversarial divorce that omits court presence is available under certain circumstances.

The action for divorce in Connecticut began as a concept in search of a means. The founders believed that Jesus did not completely reject divorce but had merely put restrictions on what was freely allowed by the Old Testament codes. The Puritans, disagreeing with the British restrictions of the time, saw divorce as an evil, necessary to quiet community discontent, In Connecticut, the legislature was used as the chosen forum early in the development of divorce, until the court system came to be viewed as the better jurisdiction.

The divorce system developed from concept that the state must have a role in every marriage. The religion of the Puritans also produced the concept of fault, which led to an adversary system, requiring a complaint, proof, and the right to appeal. But divorce was also affected by the desire for the possibility of reconciliation. This mediation required cooperation and privacy between the parties. Ease in obtaining the divorce without long waiting periods was also a factor. Thus a balance was struck over time. Divorce was to be granted by the state, but it moved from its beginnings in the legislature to the courts. Now the more personal and equitable facets are even pushed out of the courtroom into pre-trial stages, often handled by non-governmental means. Connecticut’s approach has gradually become a model for other jurisdictions throughout our country and indeed the English-speaking world.

Henry S. Cohn is a former judge of the Connecticut Superior Court and presently serves as a Judge Trial Referee. This article is based on two essays by the author: ‟Connecticut’s Divorce Mechanism,” (American Journal of Legal History, 1970), and ‟Zephaniah Swift and Divorce,” (Connecticut Supreme Court History, 2009). He co-wrote with Christopher A. Griffin “Senator Brandegee Stonewalls Women’s Suffrage” (Spring 2016.)