(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2018

During the War of 1812 Captain Richard Coote of the British brig Borer reported to the admiralty that his marines had rowed up the Connecticut River to Essex Harbor and burned merchantmen, privateers, and one pleasure boat. That pleasure boat, then a rarity, was owned by Ebenezer Hayden, one of the wealthiest merchants in Connecticut.

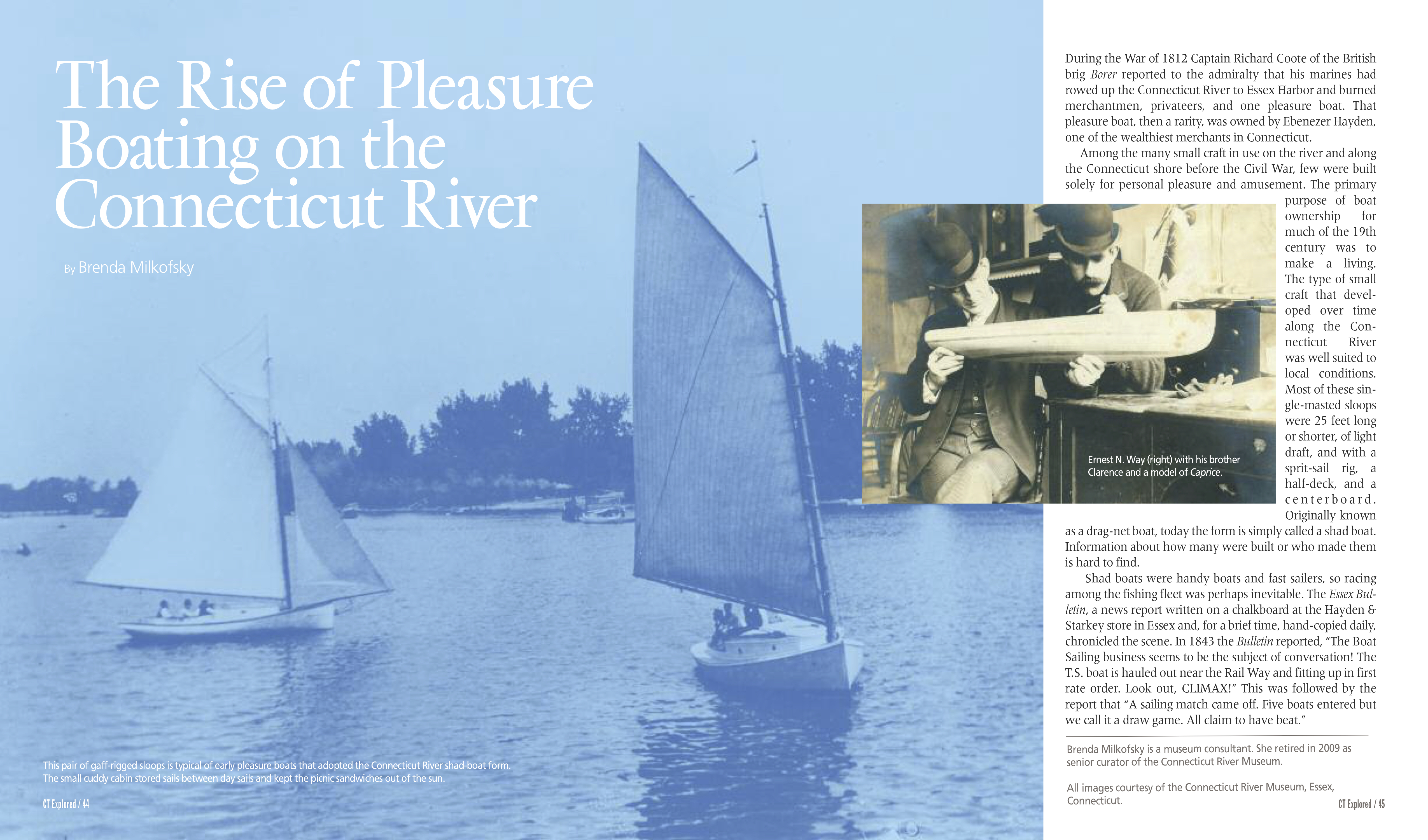

Among the many small craft in use on the river and along the Connecticut shore before the Civil War, few were built solely for personal pleasure and amusement. The primary purpose of boat ownership for much of the 19th century was to make a living. The type of small craft that developed over time along the Connecticut River was well suited to local conditions. Most of these single-masted sloops were 25 feet long or shorter, of light draft, and with a sprit-sail rig, a half-deck, and a centerboard. Originally known as a drag-net boat, today the form is simply called a shad boat. Information about how many were built or who made them is hard to find.

Shad boats were handy boats and fast sailers, so racing among the fishing fleet was perhaps inevitable. The Essex Bulletin, a news report written on a chalkboard at the Hayden & Starkey store in Essex and, for a brief time, hand-copied daily, chronicled the scene. In 1843 the Bulletin reported, “The Boat Sailing business seems to be the subject of conversation! The T.S. boat is hauled out near the Rail Way and fitting up in first rate order. Look out, CLIMAX!” This was followed by the report that “A sailing match came off. Five boats entered but we call it a draw game. All claim to have beat.”

Boating for Recreation Catches On

Boating for Recreation Catches On

In the years following the Civil War, as more people left farming for jobs in shops and factories, boating for recreation was discovered by a new population. The workweek contracted from six to five-and-a-half days, and by 1915 the two-day weekend was becoming standard. National magazines such as Outing encouraged people to get outside for their health, and the popularity of the canoe floated in on the wave of this outdoor movement.

A display of canoes at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876 spurred a new, large audience of enthusiasts. Canoes were portable and affordable, and paddling skills could be quickly learned. The Hartford Canoe Club formed in 1881, and its members were frequent visitors to the Springfield club for races. They put their boats aboard a special car of the New York & New England Railroad and later paddled home downstream.

Well into the 1930s small boats had no place along working waterfronts. Several clubhouses were built on barges where small craft could tie up out of harm’s way. The Hartford Barge Club, founded in 1927, was home to 51 single-man rowing shells stored on racks around the lower floor, according to Hartford Yacht Club historian Fred Dayton in his informal club history. The Mattabesett Canoe Club, founded in 1896 in Middletown, allowed owners of other types of boats to join as associate members, and it wasn’t long before boat owners of deeper-draft sailboats and large steam yachts began to organize their own clubs and to build clubhouses and docks for tying up.

In the 1920s and 1930s a pleasure boating industry developed quickly along the Connecticut River, and technology changed the game. The successful use of the internal combustion engine for boat motors, both inboard and outboard, invited to yachting numbers of people with no previous boating experience.

Powerboats captured the attention and pocketbooks of some of the same people who were buying the new automobile. Insurance executives, attorneys, and business owners, many of whom owned large motor yachts, were on the founding boards of yacht clubs in Hartford (1892), New Haven (1899), Middletown (1901), and Meriden (1909; this club had an anchorage in Middletown harbor). These businessmen provided potent leadership for yacht clubs such as Wethersfield Cove Yacht Club, whose minutes show that the club lobbied for dredging and for lights and channel markers along the Connecticut River.

At an unknown date, the Hartford Yacht Club moved from a blacksmith shop at the foot of State Street to rented quarters next to a coal dock at the foot of Grove Street. Later it moved to a large houseboat tied up to the west bank near the Bulkeley Bridge. When Thomas O. Enders, president of Aetna, was commodore of the club, he used Hartford Fire Insurance executive William Watrous’s steam yacht Agnes as the committee boat for races in Hartford and Essex Harbor, where the club later had a station upstairs in the Steamboat Dock.

Albert L. Pope, son of Hartford bicycle and automobile maker Colonel Albert Pope, was a HYC founding member. In 1906 Ernest N. Way designed and built a fast commuter-type boat for him named Columbia, after the bicycle that made the Pope name famous. Way and his father owned the Henry R. Way Tobacco Co. and had a warehouse on Wethersfield Cove, where Ernest designed and built his first boats. He tested hull forms on Wethersfield Cove by towing small, carved models behind a boat with a fishing rod, adding pennies to change the weight. He developed a theory of hull design that he adhered to for the rest of his career. He told The Hartford Times in 1930, “The logical under-water cross-section of the hull should form the arc of a circle if the owner is seeking a combination of speed, strength, lightness, smoothness and safety.”

In 1917 Hartford attorney and former HYC commodore Charles A. Goodwin purchased a boatyard in Essex with a plan to contribute to the war effort. He named it the Dauntless Shipyard after Caldwell Colt’s famous schooner yacht that, in the late 1880s, Colt brought to Essex for the hunting season and over-wintering. Goodwin invited Way to apply his knowledge of motor-boats to design a fast torpedo-patrol boat for use by the U.S. Navy off the New England coast. Governor Marcus Holcomb spoke at the launching amid some fanfare on July 7, 1917, and Way soon became the shipyard’s superintendent, overseeing boat construction and continuing to experiment with boat designs.

Way designed small craft, too. In 1920 Director R.C. Peck of the United States National Museum (later the Smithsonian) accepted a model of Way’s Essex for what would become the National Watercraft Collection. In October 1920 Yachting magazine reported that in accepting it Peck said, “it perpetuates the fine points of the celebrated old time Connecticut River dragnet boats, fast-sailing and weatherly.”

The Dauntless Shipyard quickly became the largest on the river, and it turned out small-class boats adopted by sailing clubs and large yachts from the drawing boards of national designers such as John Alden. Way continued to experiment and perfect lightweight designs for the new sport of speedboat racing.

Speed Racing on the River

“Toy,” designed by Ernest Way in 1930, broke records on the Connecticut River. It’s now in the collection of Mystic Seaport. Image courtesy of Connecticut River Museum

In 1930 Middletown won out over four other east-coast cities—including Boston and Charleston—to host the two-day National Outboard Championships that October. Way had designed two boats in the race. Toy, driven by Elliott Spencer of Westbrook, had shattered records at a race the previous Memorial Day in Worcester, Massachusetts. Now in the collection at Mystic Seaport, Toy entered that race weighing 63 pounds without a motor, a real featherweight compared to the average boat in its class. Toy broke four world records in Class B, speeding 40 miles per hour on the straightaway. Stunned by the vessel’s combination of weight and speed, the national racing commission passed a new weight rule requiring all boats to weigh at least 150 pounds.

Way worked with Toy’s builder, W. F. Harrison of Essex, to bring the speedboat up to the new weight rule for the national championship. Rather than simply adding ballast, he replaced the planking with “1/2 inch stuff, it nearly broke my heart,” he told The Hartford Times. Toy weighed 160 pounds at race time.

The Middletown Press reported, “With 22 world records broken in two days of racing here the marks were ready for further assaults as two more records tumbled in the first races of the day. Elliott A. Spencer of Westbrook thrice record-setter in Class B Division 1 set a still higher mark of 41.002 mph and incidentally won the world’s championship in that class. He set two records on Saturday and those were superseded by today’s mark. The original record was set in Worcester last May.”

Way died in 1939, three years after the 1936 flood that ruined boat-houses, docks, and buildings along the shoreline and a year after the Hurricane of 1938. The hurricane dashed yachts in the water to bits as the river rose six feet in three hours and winds recorded as high as 88 miles per hour lashed the region. With World War II on the horizon, yachting did not fully recover until after the war, when new materials and changing technologies invigorated new regional designers and boat builders.

Brenda Milkofsky is a museum consultant. She retired in 2009 as senior curator of the Connecticut River Museum.

Explore!

Connecticut River Museum

67 Main Street, Essex

ctrivermuseum.org