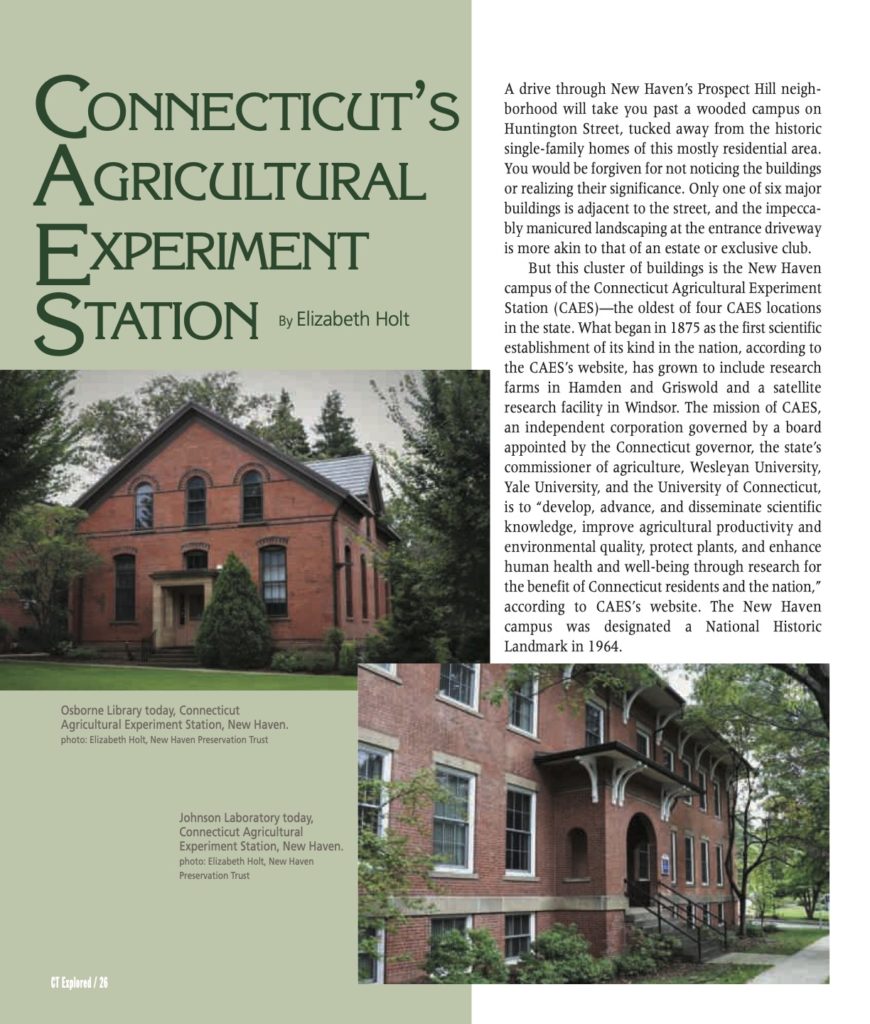

top: Osborne Library today, Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, New Haven. photo: Elizabeth Holt, New Haven Preservation Trust; below: ohnson Laboratory today, Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, New Haven. photo: Elizabeth Holt, New Haven Preservation Trust

By Elizabeth Holt

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

A drive through New Haven’s Prospect Hill neighborhood will take you past a wooded campus on Huntington Street, tucked away from the historic single-family homes of this mostly residential area. You would be forgiven for not noticing the buildings or realizing their significance. Only one of six major buildings is adjacent to the street, and the impeccably manicured landscaping at the entrance driveway is more akin to that of an estate or exclusive club.

But this cluster of buildings is the New Haven campus of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station (CAES)—the oldest of four CAES locations in the state. What began in 1875 as the first scientific establishment of its kind in the nation, according to the CAES’s website, has grown to include research farms in Hamden and Griswold and a satellite research facility in Windsor. The mission of CAES, an independent corporation governed by a board appointed by the governor, the state’s commissioner of agriculture, Wesleyan University, Yale University, and the University of Connecticut, is to “develop, advance, and disseminate scientific knowledge, improve agricultural productivity and environmental quality, protect plants, and enhance human health and well-being through research for the benefit of Connecticut residents and the nation,” according to CAES’s website. The New Haven campus was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1964.

The Station’s Founding

top: Wilbur O. Atwater, Semi-Centennial of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 1875 – 1925, 1925. below: Samuel Johnson, Popular Science Monthly, Volume 43.

The founding of CAES is attributed to Wilbur Olin Atwater and his mentor, Yale College professor of agricultural chemistry Samuel W. Johnson, both visionaries in the application of chemistry to agriculture. According to fellow scientist Thomas B. Osborne in his 1911 biography of Johnson for the National Academy of Sciences, Johnson grew up on a farm in Kingsboro, New York, where at an early age he developed an interest in the scientific side of plant and animal life. Determined to apply the use of chemical analysis to the field of agriculture and to further his education, in 1849 Johnson sought out the instruction of J.P. Norton, professor of scientific agriculture at Yale College. He was also influenced by the work of Benjamin Silliman and James Dwight Dana. After time spent studying organic and physiological chemistry in Europe, Johnson returned to Yale in 1855 invigorated and ready to develop an institution in the United States for the advancement of scientific agricultural studies.

During the next 10 years, according to Osborne, Johnson worked diligently to develop broader interest in a scientific approach to agriculture and advocated for the benefit to the agricultural community of an experiment station. He contributed papers to agricultural journals and to the American Journal of Science and Arts, gave lectures throughout New England and at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., and attended meetings of agricultural societies and farmers’ clubs.

Meanwhile, according to the National Park Service’s National Register nomination for the CAES buildings, Wilbur Olin Atwater, also of New York and a former student and assistant of Johnson’s, “helped to found the science of agricultural chemistry in America” with his doctoral thesis in 1869 for Yale about the chemical composition of maize. In his thesis Atwater discussed the possibilities of applying advances in chemistry to agriculture. He became a professor of chemistry at Wesleyan University in 1873 and worked to stimulate widespread interest in agricultural chemistry. He joined others concerned with farming at a convention in 1872 in Washington, D.C., to advocate for the creation of agricultural experiment stations across the United States.

The advocacy of Atwater, Johnson, and others paid off when, in 1875, the Connecticut General Assembly passed a bill to appropriate funds for two years for the creation of an agricultural research institution at Wesleyan. The location was chosen because Wesleyan offered free quarters in Orange Judd Hall of Chemistry and $1,000 from Orange Judd, an American agricultural publisher and columnist. Atwater was named the station’s first director.

Atwater continued Johnson’s work concerning the standards of commercially manufactured fertilizers. This research was made freely available to the public so that, for the first time, consumers could make their own judgments and comparisons of fertilizers on the open market. A report presented to the State Agricultural Society in January 1877 stated that the work of the station had saved farmers $50,000 in the cost of fertilizer. These astonishing results convinced the general assembly to establish the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station on a permanent basis. The station was moved to New Haven, temporarily housed at Yale’s Sheffield Scientific School, and Johnson was appointed director, a position in which he would remain for 23 years, according to CAES’s Semi-Centennial of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station(1925).

Atwater went on to direct the separate experiment station established at Storrs Agricultural School (now UConn) in 1887 with federal funding from the Hatch Act. The station’s fifth director, James G. Horsfall, in The Pioneer Experiment Station, 1875 to 1975, A History (Antoca Press, 1992), describes the “curious situation” of Connecticut’s two agriculture experiment stations. In 1880 farmers Charles and Augustus Storrs offered 170 acres of land, a former orphanage, and $6,000 to the Connecticut Board of Agriculture to establish a school of agriculture. Storrs Agricultural School began offering classes the following year. In 1888 a committee was appointed to assure a “harmony of work” between the two stations.

The Research

CAES’s research was groundbreaking from its earliest days. The agency reached out to Connecticut’s farmers with a message: “have nothing to do with any dealer in fertilizers who refuses to place his articles under [the station’s]supervision. In buying, endeavor to select those [fertilizers]which furnish, in the best forms and at the lowest cost, the plant-food which your crops need, and your soils fail to supply.”

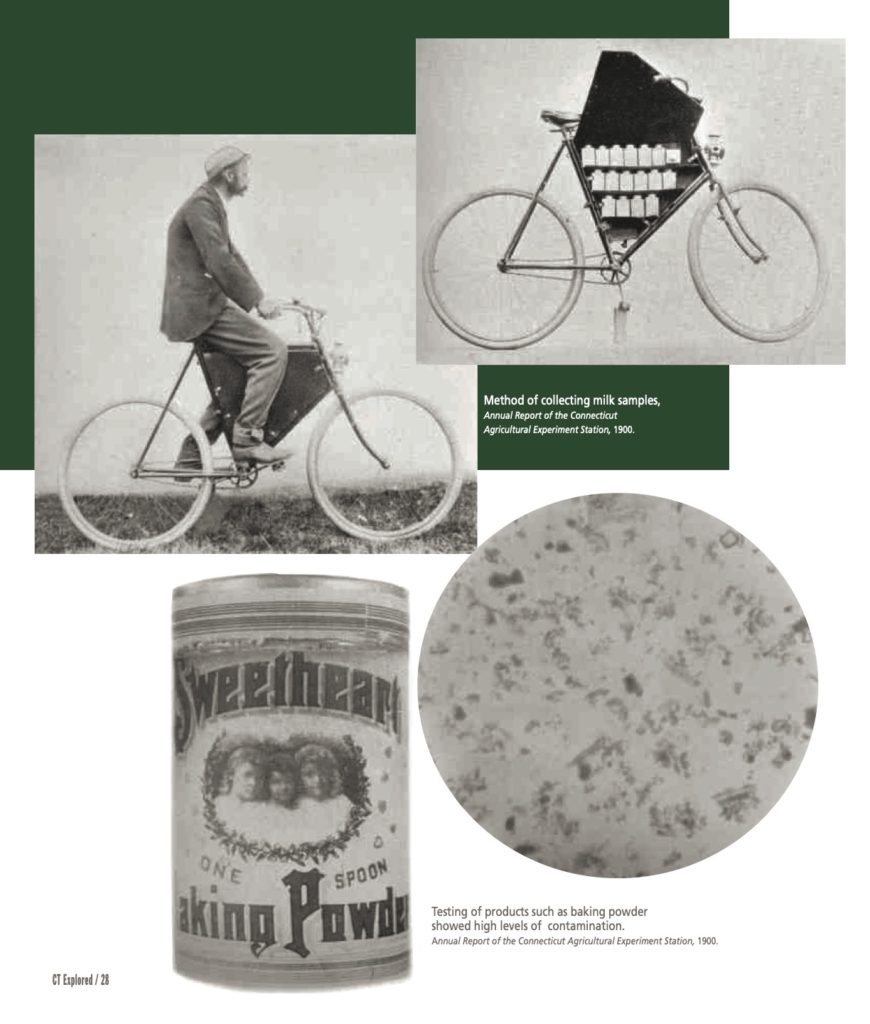

Transparency and availability of information remained a keystone of CAES’s operations. The station’s scientists soon branched into other areas of research such as analysis of animal feed, food, drugs, and toxic substances. According to Horsfall, as early as 1882 milk and butter came under scrutiny when chemists reported the frequency of the adulteration of milk. In 1895 the state legislature passed a food-quality law after the station’s analysis of pepper, coffee, maple syrup, and 10 other foods showed that 30 percent of the samples tested were adulterated. The new law had an impact. Reports from years following its passage showed a marked decline in the adulteration of coffee, for instance, from 63 percent in 1893 to just 10 percent in 1899.

top: Method of collecting milk samples, Annual Report of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, 1900; below: Testing of products such as baking powder showedhighlevelsof contamination. Annual Report of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station, 1900.

With the passage of the federal Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, the station’s chemists began to examine drugs, as Horsfall notes. The station’s analysis determined two headache medications then in use, acetanilide and acetaphenetidin, were dangerous. The station’s 1912 report described the use of heroin at “an alarming extent as a substitute for cocaine and similar habit-forming drugs” and noted that “the abuse of these drugs has become so great that New Haven has passed an ordinance prohibiting its use except on prescription.” In 1914 the station’s annual report said that its chemical department was frequently called upon to identify drugs that had been confiscated by the police.

Horsfall asserts that perhaps the most valuable contribution ever made by the station was the method of producing hybrid corn. Corn quickly exhausts the soil, reducing crop yields in fields year over year. A 1906 bulletin published by the station, “The Improvement of Corn in Connecticut,” described the development of the hybridization of corn. Station scientists Edward M. East and Herbert K. Hayes had begun attempts to increase the quality and yield of corn through selective breeding. Because corn is a self-fertilizing plant, East realized that preventing self-fertilization made it easier to breed for selective desirable traits. Hayes and East then discovered that crossbreeding two inbred varieties produced hardier crops, though they also learned that those improvements were lost over successive generations.

Donald F. Jones, then 25, joined the station in 1914. He built upon the work of East and Hayes and within his first few years on staff explained the increased vigor and yield found in hybrid corn. He successfully created a double-cross hybrid variety, though improvements in this strain were also lost in later generations. Nevertheless, Jones began actively promoting the technique in 1919. It would be another 30 years, after collaborating with Paul Mangelsdorf of Harvard University, before Jones would develop a way to prevent self-fertilization and thus increase the practicality and cost efficiency for farmers of hybrid corn breeding.

For this breakthrough in corn production to have happened in Connecticut makes it even more remarkable. As Horsfall reports, Henry Wallace, founder of the first company to produce commercial hybrid seed corn, expressed his reverence for Jones’s accomplishment in a speech at the Station Summer Field Day in 1955. Wallace cited the relatively small size of CAES and the relatively small acreage of Connecticut’s corn fields compared to the experiment stations and acreage of the Corn Belt states, and yet, he said, “No state agricultural experiment station has ever accomplished so much with so little land, money, and salaries.”

The Station Expands

For a few years the station conducted its work in Sheffield Hall at the corner of Grove and Prospect streets, but soon Yale needed that space for students. The CAES board selected a site on Suburban Street (now Huntington Street) for the station’s next home, funded by a $25,000 appropriation by the state legislature, according to the National Register nomination. The five-acre tract of land was purchased from Eli Whitney Jr., with several buildings on it, including a large wood-frame house and barn, an ice house, and a well. A brick two-story chemical building, now the Osborne Library, was constructed in 1882, the year the station moved to the site.

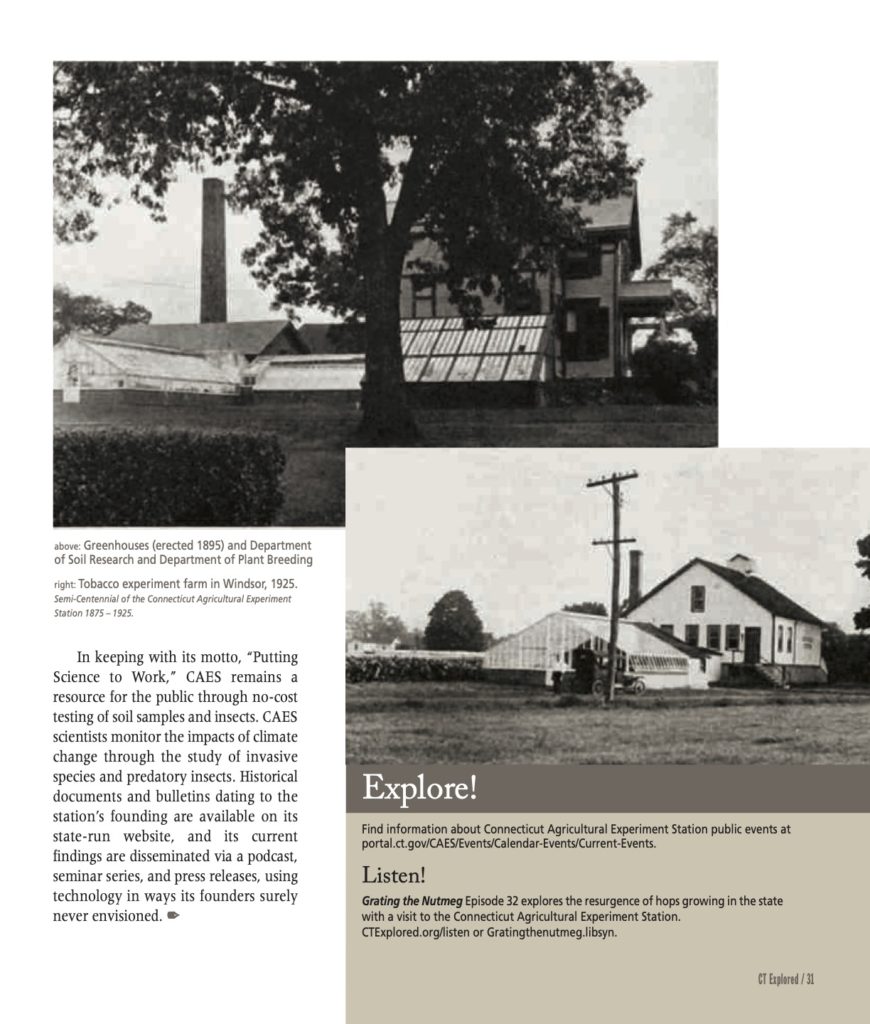

The Hatch Act, passed by the U.S. Congress in 1887, provided federal funding for an experiment station in each state. These were usually connected with an agricultural college, which in Connecticut’s case was, by then, the Storrs Agricultural School. Connecticut’s senators worked to ensure CAES was not excluded from funding under the act. Expansion continued with a forage garden to experiment with food for grazing animals.

Around the turn of the 20th century William Raymond Lockwood, a resident of Norwalk, bequeathed his estate to the station, which was subsequently sold. Proceeds went toward the purchase of 20 acres in Hamden in 1909. Now called Lockwood Farm, the land has been used to test organically-derived fungicides, and since 1931 farm managers have taken daily weather measurements used to study Connecticut’s climate.

top: Greenhouses (erected 1895) and Department of Soil Research and Department of Plant Breeding; below: Tobacco experiment farm in Windsor, 1925. Semi-Centennial of the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station 1875 – 1925.

The Valley Laboratory in Windsor was added in 1921. Originally referred to as the Tobacco Substation, the Windsor facility was used to improve the quality of tobacco leaves for use as fine cigar wrappers. Today, research conducted there involves invasive-plant management, integrated pest management, and management of the exotic hemlock woolly adelgid.

The most recent addition to CAES is the Griswold Research Center, which encompasses 14 acres of farmland in Griswold and Voluntown. Acquired from the Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection in 2008, the center has focused on activities such as the study of cold-hardy grape vines and the production of biofuel from rapeseed. The state bee inspector keeps an office there.

It’s the original New Haven location, though, that holds the distinction of being a National Historic Landmark, designated in 1964. The station’s oldest building on the campus, the Osborne Library, is generally believed to be the country’s oldest built for the purpose of agricultural experimentation. First used as a laboratory and later converted to the station’s library, its exterior has remained relatively unchanged, except for the removal of several chimneys along the roofline. The Johnson Laboratory is the second-oldest building on the campus, constructed circa 1890. The Jones Auditorium, built in the 1930s, was a project of the Works Progress Administration.

While several buildings are significant, contributing to the site’s National Historic Landmark des

ignation, it’s the advancements in science and agriculture for which the station is most notable. In addition to the development of hybrid corn and advances in food safety, in 1909 Thomas B. Osborne and Lafayette Mendel’s experiments with amino acids led to the discovery of vitamins. In 1945 M.F. Morgan developed the first widely accepted method of effectively testing soil fertility. And in 1975, when a string of juvenile patients presented with symptoms of arthritis in Lyme and Old Lyme, scientists at the station discovered they had a disease carried by ticks.

The Station Today

CAES has had only 10 directors in its almost 150-year history. Dr. Jason White was appointed on April 1, 2020. He joined the research staff of the station in 1997 and was most recently the chief scientist for the CAES department of analytical chemistry. In this role he directed state- and federally-funded research and surveillance that focused on the environment, consumer products, and food.

In keeping with its motto, “Putting Science to Work,” CAES remains a resource for the public through no-cost testing of soil samples and insects. CAES scientists monitor the impacts of climate change through the study of invasive species and predatory insects. Historical documents and bulletins dating to the station’s fo

unding are available on its state-run website, and its current findings are disseminated via a podcast, seminar series, and press releases, using technology in ways its founders surely never envisioned.

Elizabeth Holt is director of preservation services for New Haven Preservation Trust. She last wrote “Site Lines: Coy Takes the Telephone to the Masses,” Winter 2020-2021.

Explore!

Find information about Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station public events at portal.ct.gov/CAES/Events/Calendar-Events/Current-Events.

Listen

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 32 explores the resurgence of hops growing in the state with a visit to the Connecticut Agricultural Experiment Station.