(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2018

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

For generations sports writers and novelists have waxed philosophical about how baseball reflects the American spirit and sense of fair play. But our nation’s history is more complicated than that. For 100 years, the baseball field was a battleground for civil rights, and black athletes were often the casualties. African American players were common in the earliest days of the game, until post-Civil War segregation took hold in every sphere of public life.

Connecticut bucked that racist trend sometimes, and the quality of baseball was better for it. The fans knew good players when they saw them. But as history tells us, and the journal Sporting Life editorialized on April 11, 1891 “Probably in no other business in America is the color line so finely drawn as in baseball. An African who attempts to put on a uniform and go among a lot of white players is taking his life in his hands.” Despite this, Connecticut fans saw many of the great black players play right here.

Ulysses Franklin Grant and Moses Fleetwood Walker

Ulysses Franklin Grant and Moses Fleetwood Walker

Before the color line hardened, two African American greats played for Connecticut teams in the Eastern League, a semi-professional group of New England and Canadian baseball clubs.Ulysses Franklin “Frank” Grant, born in Pittsfield, Massachusetts, played second base in 1886 for Meriden (known as the Maroons or Silvermen). Ohioan Moses Walker was a catcher during the 1885 – 1886 seasons for the Waterbury Brassmen.

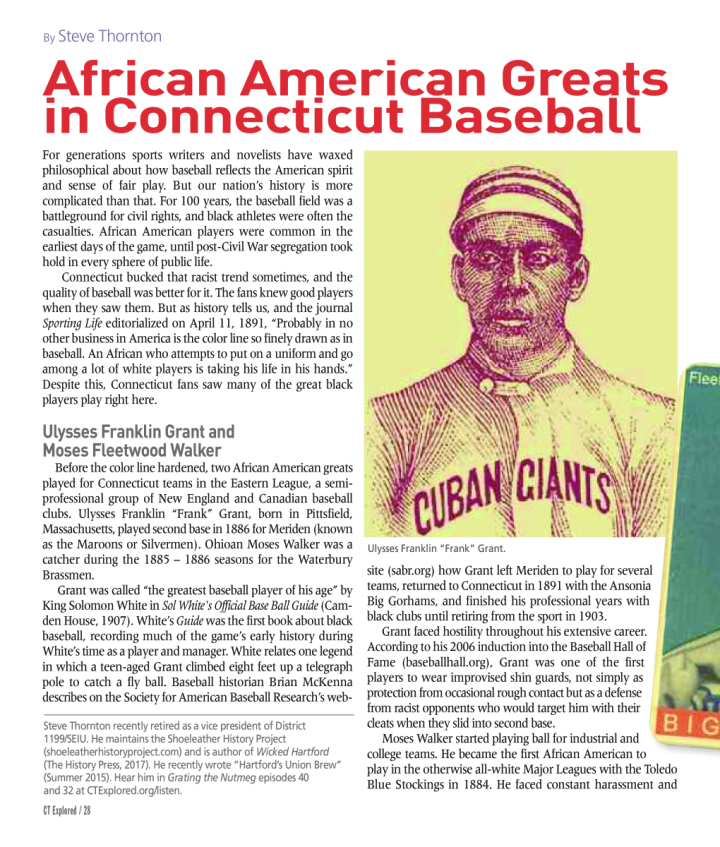

Grant was called “the greatest baseball player of his age” by King Solomon White in Sol White’s Official Base Ball Guide(Camden House, 1907). White’s Guidewas the first book about black baseball, recording much of the game’s early history during White’s time as a player and manager. White relates one legend in which a teen-aged Grant climbed eight feet up a telegraph pole to catch a fly ball. Baseball historian Brian McKenna describes on the Society for American Baseball Research’s website (sabr.org) how Grant left Meriden to play for several teams, returned to Connecticut in 1891 with the Ansonia Big Gorhams, and finished his professional years with black clubs until retiring from the sport in 1903.

Grant faced hostility throughout his extensive career. According to his 2006 induction into the Baseball Hall of Fame (baseballhall.org), Grant was one of the first players to wear improvised shin guards, not simply as protection from occasional rough contact but as a defense from racist opponents who would target him with their cleats when they slid into second base.

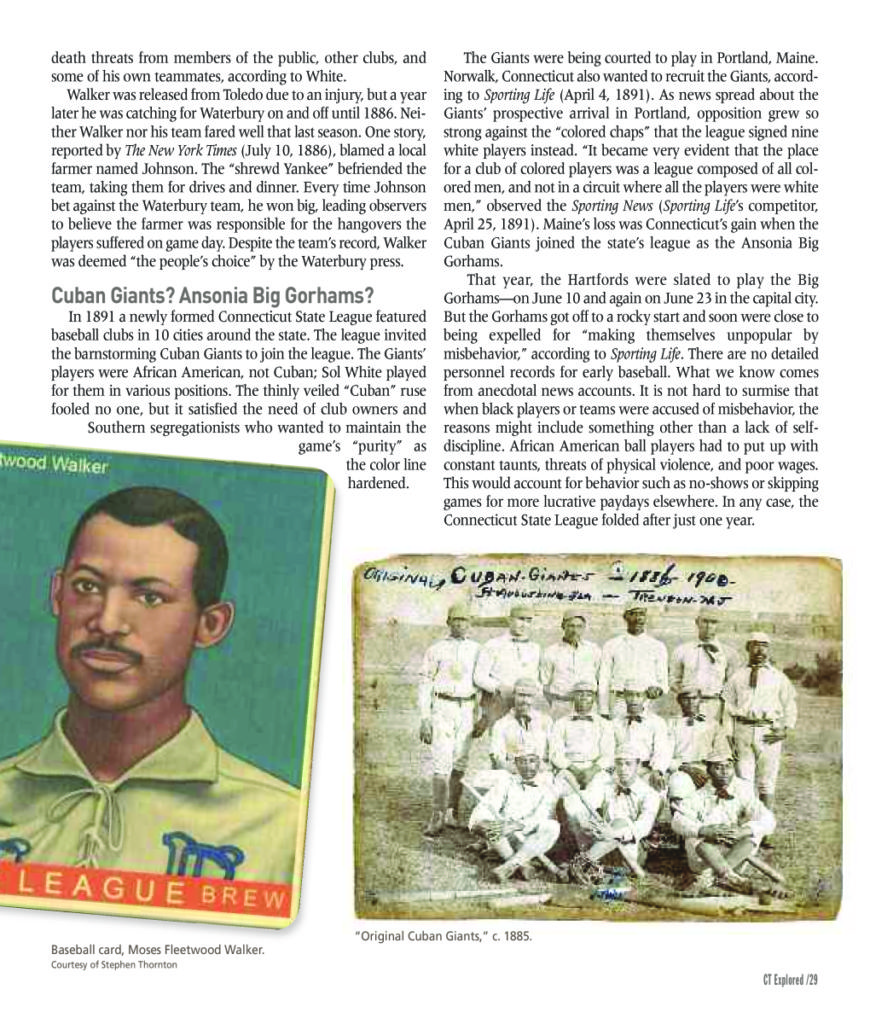

Moses Walker started playing ball for industrial and college teams. He became the first African American to play in the otherwise all-white Major Leagues with the Toledo Blue Stockings in 1884. He faced constant harassment and death threats from members of the public, other clubs, and some of his own teammates, according to White.

Walker was released from Toledo due to an injury, but a year later he was catching for Waterbury on and off until 1886. Neither Walker nor his team fared well that last season. One story, reported by TheNew York Times(July 10, 1886), blamed a local farmer named Johnson. The “shrewd Yankee” befriended the team, taking them for drives and dinner. Every time Johnson bet against the Waterbury team, he won big, leading observers to believe the farmer was responsible for the hangovers the players suffered on game day. Despite the team’s record, Walker was deemed “the people’s choice” by the Waterbury press.

Cuban Giants? Ansonia Big Gorhams?

In 1891 a newly formed Connecticut State League featured baseball clubs in 10 cities around the state. The league invited the barnstorming Cuban Giants to join the league. The Giants’ players were African American, not Cuban; Sol White played for them in various positions. The thinly veiled “Cuban” ruse fooled no one, but it satisfied the need of club owners and Southern segregationists who wanted to maintain the game’s “purity” as the color line hardened.

The Giants were being courted to play in Portland, Maine. Norwalk, Connecticut also wanted to recruit the Giants, according to Sporting Life(April 4, 1891).As news spread about the Giants’ prospective arrival in Portland, opposition grew so strong against the “colored chaps” that the league signed nine white players instead. “It became very evident that the place for a club of colored players was a league composed of all colored men, and not in a circuit where all the players were white men,” observed the Sporting News (Sporting Life’s competitor, April 25, 1891). Maine’s loss was Connecticut’s gain when the Cuban Giants joined the state’s league as the Ansonia Big Gorhams.

That year, the Hartfords were slated to play the Big Gorhams—on June 10 and again on June 23 in the capital city. But the Gorhams got off to a rocky start and soon were close to being expelled for “making themselves unpopular by misbehavior,” according toSporting Life.There are no detailed personnel records for early baseball. What we know comes from anecdotal news accounts. It is not hard to surmise that when black players or teams were accused of misbehavior, the reasons might include something other than a lack of self-discipline. African American ball players had to put up with constant taunts, threats of physical violence, and poor wages. This would account for behavior such as no-shows or skipping games for more lucrative paydays elsewhere. In any case, the Connecticut State League folded after just one year.

Louis Francis Sockalexis was a Penobscot Indian born in Old Town, Maine in 1871. He demonstrated great athletic ability as a teenager and played a variety of sports as a student at College of the Holy Cross in 1895 and 1896 and for brief time at the University of Notre Dame.

But baseball was his game, and he was recruited to the National League’s Cleveland Spiders in 1897. Sockalexis played with greats such as Cy Young and hit .338 in his first 60 games, leading Hall of Famer John McGraw to call him the greatest natural talent he had ever seen. Sockalexis spent two full seasons in the big league with Cleveland.

Separated from his home, people, and the forests of Maine, “Sox” became an early victim of hard drinking and fast living and a target of frequent hostility and racism from crowds and other players. Early in the 1899 season Sockalexis was released by the Spiders after his performance suffered, due in part to an alcohol-related injury. He was immediately picked up by the Hartford Indians while that team was in New York playing the Rochester Broncos. Both clubs were part of the Eastern League. It wasn’t the big time, but for Sockalexis, it was still baseball.

At Sockalexis’s first home game in Hartford on May 29, a local sports writer described him as “a tower of strength in left garden.” He was a “swift, accurate thrower,” TheCourantreported the next day: At bat, “‘Sox’ has no superior in the league. He has made many of the big pitchers in the National League look anxious,” TheCourantconcluded. That day, the Indians beat the Springfield Ponies 6-1.

The high point for Sockalexis came in a subsequent home game in June against Springfield. Although it was a weekday, more than 4,500 Hartford fans showed up to the south-end field, filling the bleachers and free stands, perched on the roof of the box seats, and circling the field.

In an early inning the opposing pitcher walked Sockalexis, afraid of what his bat could still do. But the next time he walked to the plate, Sox reached for the ball and connected. “With a mighty swing he pounded the sphere, sprinted off to the West, while Warriors Shindle and Kelly galloped to the plate. A yell smote the forest.” The Courantreported on June 17, 1899 that Sockalexis drove in four runs that day and was given “tumultuous applause for his work with the stick.”

The young player had not beaten his alcohol addiction when he moved to Hartford, though. Although he had promised his manager that he would reform, temptation was all around. More than 180 saloons crowded Hartford streets at the time. Within a short time, published stories circulated that Sox was “working the night-owl racket.” The last Hartford account written about him (The Hartford Courant, June 19, 1899) revealed that “the Penobscot kept bad hours, and as a result when he went after a ball his movements reminded one of a messenger boy on an errand.”

After Hartford, Sockalexis took another step down professionally, this time to a re-formed Connecticut State League. First recruited by a team in Bristol, Sox was quickly stolen away by Roger Connors’s Waterbury club, where he successfully finished out the season and helped the team reach second place. The Waterbury Republicanfeatured Sox’s outstanding exploits every game day in August 1899.

Sadly, by the spring of 1900 Louis Sockalexis was back in Hartford, not as a player but as a vagrant who frequented Front Street taverns. His biographer Brian McDonald wrote in Indian Summer: The Tragic Story of Louis Francis Sockalexis (Rodale Books, 2003) thatthe unemployed player briefly worked in some capacity for Colt Firearms. Sockalexis moved closer and closer to home, first to Massachusetts, then to Maine, still involved with baseball as a player, an umpire, or a coach for aspiring young Penobscot ball players. He died in 1913 on Christmas Eve while working as a logger in Maine.

The Cubans at Electric Field

Bonafide Cuban ball players were recruited by the New Britain Aviators in 1908, attracting great attention when they faced off against other teams in the Connecticut State League. The Aviators (also known as the Perfectos) played their home games at New Britain’s Electric Field. They recruited a number of Cubans, including shortstop Alfredo (“Pájaro”) Cabrera, left fielder Armando Marsans, and third baseman Rafael Almeida, all of whom played in New Britain for four seasons, from 1908 to 1910, the New Britain Herald reported.

Manager Dan O’Neil facilitated the sale of Marsans and Almeida to the Cincinnati Reds in 1911. By 1915 the two were back home with the National Cuban League. In 1915 Cabrera, who began his career in 1902 and played with local teams including Waterbury and Springfield, was also back in Cuba and took the Almendares team to a pennant victory as player-manager.

The Hardware City continued to recruit Cuban players and in 1908 signed Luis (“Mulo”) Padrón, a remarkable player who began his career in 1900 and came to the United States in 1905, according to baseball-reference.com.Padrón was playing in New York and had pitched a no-hit game when the Aviators found him. A fast runner with a strong arm who could play any position, Padrón was credited that year with having hit the longest homer ever at Electric Field.

Still, Padrón became a victim of American racism. The Cubans’ time in New Britain stirred up local prejudice to such an extent that after the 1908 season the Aviators’ owners traveled to Cuba to determine the race of their Latino players. According to Adrian Burgos Jr. (Latino/a Popular Culture, New York University Press, 2002), it was decided by some unspecified racial formula that Padrón was black, but that the other three were white “Spaniards.” This blocked Padrón from further employment on white teams.

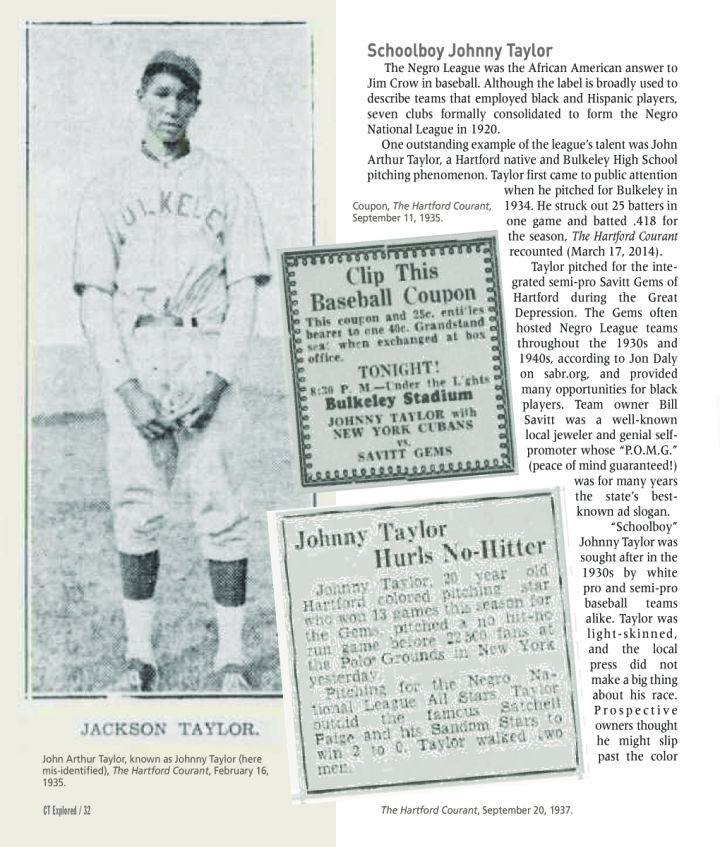

The Negro League was the African American answer to Jim Crow in baseball. Although the label is broadly used to describe teams that employed black and Hispanic players, seven clubs formally consolidated to form the Negro National League in 1920.

One outstanding example of the league’s talent was John Arthur Taylor, a Hartford native and Bulkeley High School pitching phenomenon. Taylor first came to public attention when he pitched for Bulkeley in 1934. He struck out 25 batters in one game and batted .418 for the season, as The Hartford Courantrecounted (March 17, 2014).

Taylor pitched for the integrated semi-pro Savitt Gems of Hartford during the Great Depression. The Gems often hosted Negro League teams throughout the 1930s and 1940s, according to Jon Daly on sabr.org, andprovided many opportunities for black players. Team owner Bill Savitt was a well-known local jeweler and genial self-promoter whose “P.O.M.G.” (peace of mind guaranteed!) was for many years the state’s best-known ad slogan.

“Schoolboy” Johnny Taylor was sought after in the 1930s by white pro and semi-pro baseball teams alike. Taylor was light-skinned, and the local press did not make a big thing about his race. Prospective owners thought he might slip past the color line. Taylor could have played for the New York Yankees, who made him an offer, but he refused to pose as a Cuban as a team scout suggested, according to Daly.

Taylor instead played for the Negro League Cuban Giants and the Cuban Stars. He played in Mexico and Cuba, and in Winsted and Waterbury with Casey Stengel, future manager of the New York Yankees. He was mentored by “El Maestro” (the teacher) Martin Dihigo, an extraordinary Cuban pitcher who played for the Eastern League Colored Stars and Cuban teams.

The legendary Satchel Paige met up with the young Taylor when his Paige All-Stars faced the Negro League All Stars in 1937 at the Polo Grounds in New York. Both hurlers struck out the other side’s batters, but it was Taylor who pitched a no-hitter to clinch the game. As recorded by Larry Tye in Satchel: The Life and Times of an American Legend(Random House, 2010),the loss depressed Paige. “It’s a mighty bad feeling when a young punk comes along and does better than you and you know it,” he admitted. The next day, however, Paige led his All Stars to a 9-5 victory before 25,000 fans.

Born Too Soon?

Mahlon “Duck” Duckett and John “Mule” Miles were among the last Negro League ball players to face Connecticut teams before the Major Leagues were integrated by Jackie Robinson in 1947.

They both returned to Hartford in 2007, special guests of the Hartford Stage Company. Duckett and Miles attended a performance of Fences by August Wilson, a powerful drama about a Negro League alumnus whose chance for a big-league career had passed him by. Also in attendance was Estelle Taylor, widow of Johnny Taylor.

Duckett, an infielder who played 10 years for the Philadelphia Stars (from 1940 to 1949), remembered his earliest visits to Hartford: “We would play a game in New York, against the Black Yankees or New York Cubans. Then on our off-day, we’d travel to Hartford for an exhibition game,” he told fans after the stage play. Miles told the audience that he earned his nickname because he could “hit like a mule kicks.”He described how, when playing down South, “there was nothing but segregation and the Klan. …Our bus was our hotel, our kitchen, our dressing room.” There were insults, and worse, “but nothing you could do about it,” Duckett added.

Duckett, an infielder who played 10 years for the Philadelphia Stars (from 1940 to 1949), remembered his earliest visits to Hartford: “We would play a game in New York, against the Black Yankees or New York Cubans. Then on our off-day, we’d travel to Hartford for an exhibition game,” he told fans after the stage play. Miles told the audience that he earned his nickname because he could “hit like a mule kicks.”He described how, when playing down South, “there was nothing but segregation and the Klan. …Our bus was our hotel, our kitchen, our dressing room.” There were insults, and worse, “but nothing you could do about it,” Duckett added.

Like Fences’s character Troy Maxson, real-life Johnny Taylor faced the same tribulations but came to a different conclusion. “I’ve heard about and have been asked many times about having been born too soon,” he told Hartford Courantsports writer George Smith for an article published on July 26, 1976. “But what are you going to do? You can’t live in the past. I’ve always taken things as they come. It’s no good to dwell in the past. … I like to think that what we did in the 1930s and 1940s by barnstorming with the white teams paved the way for the next generation.” Johnny Taylor died in Hartford on June 15, 1987, just three months after the premiere of Fences on Broadway.

Steve Thornton recently retired as a vice president of District 1199/SEIU. He maintains the Shoeleather History Project (shoeleatherhistoryproject.com) and is author of Wicked Hartford(The History Press, 2017). He recently wrote “Hartford’s Union Brew” (Summer 2017). Hear him in Grating the Nutmeg episodes 40 and 32 at CTExplored.org/listen.

Explore!

LISTEN: Grating the Nutmeg Episode 117: Before 42: Ballplayers of Color in Connecticut

“The McCook Boys Collect Baseball Cards,” Fall 2009

“The Hartford Dark Blues,” Spring 2003

Find more Connecticut SPORTS history stories on our TOPICS page!

Find all of our stories about African American history on our TOPICS page!