By Steve Thornton

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2017

SUBSCRIBE/Buy the Issue!

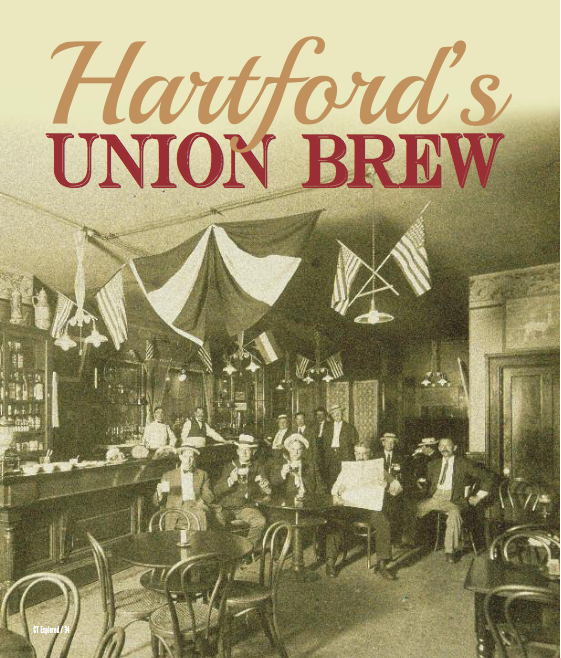

At the start of the 20th century, more than 180 saloons and taverns crowded Hartford streets. Two dozen were located on Front Street alone. There were twice as many bars in the city as there were churches and temperance groups combined, according to the listings in the 1901 Geer’s Hartford City Directory.

The Bartenders Union Local 200 organized in 1900, fighting for and winning a standard 62-hour work week. They improved bartenders’ wages as well, from an average of $9 to $15 a week.

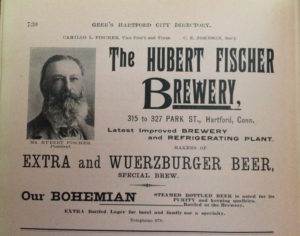

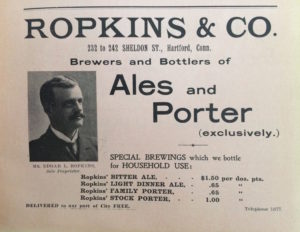

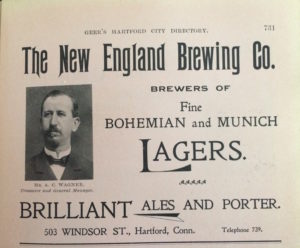

Brewery workers—the men who made the popular product the bartenders served—hoped to make similar gains. Four breweries operated in Hartford in 1902: Hubert Fischer Brewery (founded in 1886), Ropkins & Company (founded 1893), The New England Brewing Co. (founded 1897), and Aetna Brewing Company (founded 1900). It was a period of widespread labor agitation. In an effort to put pressure on the beer companies, in 1901 all Hartford saloons sold a glass of beer for a nickel. But if a thirsty man bought the same beer from a shop without a union card hanging behind the counter, it would cost him two dollars. The local Hotel, Restaurant and Bartenders’ Union, in solidarity with

the Local 35 of the Brewery Workmen, posted warnings in every union hall that the penalty for drinking a “scab” beer would cost union men roughly a day’s pay.

How such a fine was enforced is not known, but the point was clear: Hartford was a union town. The beer penalty reminded thoughtless workers that union solidarity was their only weapon against exploitation. An injury to one was an injury to all.

Local 35 was seeking the eight-hour day and better job security during slow production times in winter. As The

Hartford Courant reported (“The Beer Situation,” April 7, 1902), they bargained for more than a month, and several times the workers postponed the one final action that would force the bosses to settle—a strike.

In the meantime, company owners were making plans of their own. They began to work together to resist the demands of Local 35. The companies decided they would no longer choose their new employees from the Brewers’ Union hiring hall. The owners believed that the closed shop, as it came to be known, was a further restriction on management rights. If they needed a skilled “stationary

engineer,” they argued, they should be able to hire one even if he wasn’t a Brewer’s Union member. Another major sticking point was how to handle the termination of a brewery worker. Owners wanted an outside arbitrator, mutually agreed-upon with the union, to make the final decision. The workers wanted a say in the dismissal.

In a real sense, this was not the traditional labor fight over wages and hours. It was about power. The owners had reportedly agreed to wage increases but were holding out for concessions on hiring and firing practices. For the union, who was on the job was as important as how much he was paid.

In no other trade were such rules in effect, the owners complained. They claimed in The Courant on April 11 that brewery unions in Boston, Springfield, and Buffalo had tried and failed to win these demands. That same day, workers struck all the Hartford breweries. Beer that had just been produced stayed in the plants. “We believed that the bosses had broken their word” on demands already settled, union spokesman Richard Merchenz told The Courant.

On Strike!

Workers at two of the firms were so anxious to show their commitment to the cause that they walked out at noon ahead of the strike’s designated start time of 1:30 p.m. Production immediately went from 400 barrels a week to zero, affecting 75 percent of all the beer consumed in Hartford’s establishments. Only beer brewed out of state remained available.

Eighty-five brewery workers went on strike. Most of them were German immigrants, some had been brewing beer for 20 years. Members of the engineers, firemen, and drivers unions who also worked at the breweries walked out with the brewers in solidarity. Wages for these other workers ranged from $15 to $20 a week depending on the job, with 50 cents an hour for overtime. For the hard-working, hard-drinking members of Hartford’s working class, supporting this strike was difficult, but it was also a significant act of solidarity.

The union went to bars all over the city to make sure owners were not buying scab beer from out of town. They also went to other unions and asked them to pledge not to drink beer until the strike was settled.

The brewers’ walkout was cause for Hartford workers to re-examine their commitment to unionism in general and to union-made goods in particular. According to a Courant report on April 12, men checked each other’s suits for union labels and chastised those who smoked non-union tobacco. Some began to drink ginger ale instead of beer.

The strike posed other dilemmas. At least one teamster, as beer delivery wagon drivers were known, was upset that a scab would now be handling his horses. And the brewers decided that any pre-strike beer should not be bought or sold. This put union bartenders such as Timothy J. Sullivan in a quandary, since they had been serving union brew produced before the strike. As The Courant reported (“Union or Non-Union, April 12, 1902), he and other saloon operators had built up their supplies in anticipation of a job action, and if the beer couldn’t be sold, it would spoil. While Hartford bars such as Sutters Hall threw out the beer in question, Local 35 made allowances for stockpiled brew in the other outlets.

The owners were not idle. Needing transportation for their product, they tried to hire two different local hauling companies. Both were union, and both refused. Then the bosses went to the Connecticut Free Employment Bureau to seek job applicants. Within a few days of the walkout, the owners were hoping to start production with a scab labor force.

But after six days (including one Saturday night), the strike was over—and the workers had won. Bartenders’ Union leaders Sullivan and J.J. Murphy helped mediate a settlement. The result was impressive by any standard, as The Courant reported (“Brewers Back at Work,” April 16, 1902). The Brewers’ Union won the eight-hour day, new workers would only be hired from the union’s ranks, and fired workers could have their cases heard by an arbitration panel composed of Central Labor Union officials.

The working men of Hartford could go back to drinking their union brew. And as part of their new agreement, the brewery workers won five minutes off each hour to drink beer.

Steve Thornton recently retired as a vice president of District 1199/SEIU. He created the Shoeleather History Project (shoeleatherhistoryproject.com), and is author of A Shoeleather History of the Wobblies; Stories of the Industrial Workers of the World (Red Sun Press, 2013) and the forthcoming Wicked Hartford (The History Press).

Explored!

Read about hops growing in Connecticut: Connecticut’s Hopyards

Listen to our podcast about hops, beer, and Hartford’s brewery strike, and more! Grating the Nutmeg Episode 32.

More stories from the Summer 2017 issue