By Barbara Donahue

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2005

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Dozens of Connecticut towns played some part in the mid-19th-century drama of the Underground Railroad, but Farmington claims a starring role, with a wealth of authenticated “Railroad” sites and stories. An autumn walk through Farmington’s old village section leads you past several of these, evoking the spirits of brave fugitives and the friends who helped them in their fight. Except for the First Church of Christ, Congregational, all sites are private property and are not open to the public. However, each site is marked with a granite post placed by the Farmington Historical Society, and each post bears a metal plaque with the symbols of the “Railroad,” the North Star and a lantern.

127 Main Street holds a cluster of sites. On the right is the then-home of Austin and Jennet Cowles Williams, abolitionists and “stationmasters” on the Railroad. At some personal risk, they publicly welcomed runaways. On the left is a grey carriage house; it was built as a safe home for the survivors of the Amistad mutiny. Concealed beneath its floor is a windowless cellar, a possible “Railroad” hiding place. Though it’s no longer standing, a third important building was the modest home of Henry Davis, a farmer and fugitive from slavery himself.

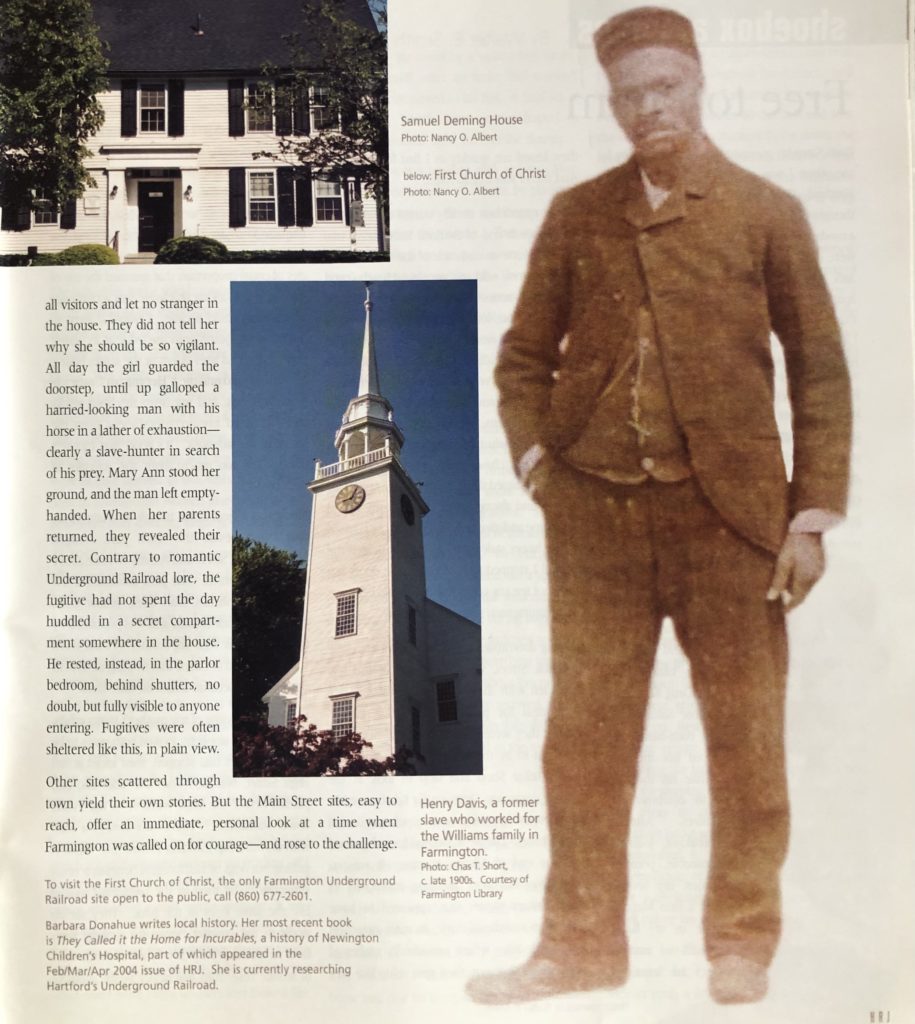

In his autobiography, Some Reminiscences of a Long Life, John Hooker, abolitionist and brother-in-law of Harriet Beecher Stowe, told Davis’s story: Henry Davis, born in Virginia, escaped bondage in South Carolina and eventually reached Farmington, where he found refuge and a job on the Williams place. After he had been in Farmington a few months, another fugitive from South Carolina came through town and reported that Davis’s former master had charged his aged mother with aiding in her son’s escape and flogged her violently.

Infuriated, Davis dared the long trip back to the South, despite its threat of capture and cruel punishment. He visited his mother and then took revenge on her oppressor by gathering eight other enslaved people and leading them north. They moved slowly because one young woman in the party was heavily pregnant and soon became unable to walk. Her husband and Davis took turns carrying her. Still, “worn out with weariness and anxiety,” as Hooker wrote, she collapsed and died. Her friends “buried her in the darkness in a secluded spot, and went on their anxious and perilous way.” Davis returned to Farmington, where he lived until his death in 1930; the others went on safely to Canada.

top: Samuel Deming House, Farmington, 2005. photo: Nancy O. Albert. below: First Church of Christ, Farmington, 2005. photo: Nancy O. Albert. right: Henry Davis, a former enslaved man who worked for the Williams family in Farmington, c. late 1900s. photo: Chas. T. Short, Farmington Library

Further up Main Street, at 116, is the home of Rev. Noah Porter, minister of the Congregational Church. He once invited a “contraband,” or fugitive, to lecture in his church. His daughter Sarah Porter, who shared her father’s abhorrence of slavery, made sure her entire school turned out to hear the man.

Further north, at 75 Main Street, is the First Church of Christ, built in 1752 and still home to an active congregation. Rev. J. W. C. Pennington, a Hartford minister and former slave, preached here at Noah Porter’s request, and Farmington’s abolitionists worshipped in this church. The spare, elegant building is open for services and can visited at other times by request.

Across from the church, at 66 Main Street, is the home of abolitionists Samuel and Catherine Deming. Catherine was among the many Farmington women who raised money and signed petitions to help the abolitionists. Because both she and her husband Samuel were so outspoken, their house has traditionally been considered a “stop” on the “Railroad,” though no individual, named fugitive is connected with it.

The last stop on Main Street is No. 27, home of Horace and Mary Ann Cowles. Once, while they were housing a fugitive, they had to leave home unexpectedly. They put their young daughter, also named Mary Ann, in charge, with strict instructions to turn away all visitors and let no stranger in the house. They did not tell her why she should be so vigilant. All day the girl guarded the doorstep, until up galloped a harried-looking man with his horse in a lather of exhaustion—clearly a slave-hunter in search of his prey. Mary Ann stood her ground, and the man left empty-handed. When her parents returned, they revealed their secret. Contrary to romantic Underground Railroad lore, the fugitive had not spent the day huddled in a secret compartment somewhere in the house. He rested, instead, in the parlor bedroom, behind shutters, no doubt, but fairly visible to anyone entering. Fugitives were often sheltered like this, in plain view.

Other sites scattered through town yield their own stories. But the Main Street sites, easy to reach, offer an immediate, personal look at a time when Farmington was called on for courage—and rose to the challenge.

To visit the First Church of Christ, the only Farmington Underground Railroad site open to the public, call (860) 677-2601.

Barbara Donahue writes local history. Her most recent book is They Called it the Home for Incurables, a history of Newington Children’s Hospital, part of which appeared in the Feb/Mar/Apr 2004 issue of HRJ. She is currently researching Hartford’s Underground Railroad.

Explore!

Rev. James Pennington: A Voice for Freedom, Winter 2012/2013

Real all of our stories about the African American experience in CT on our TOPICS page.