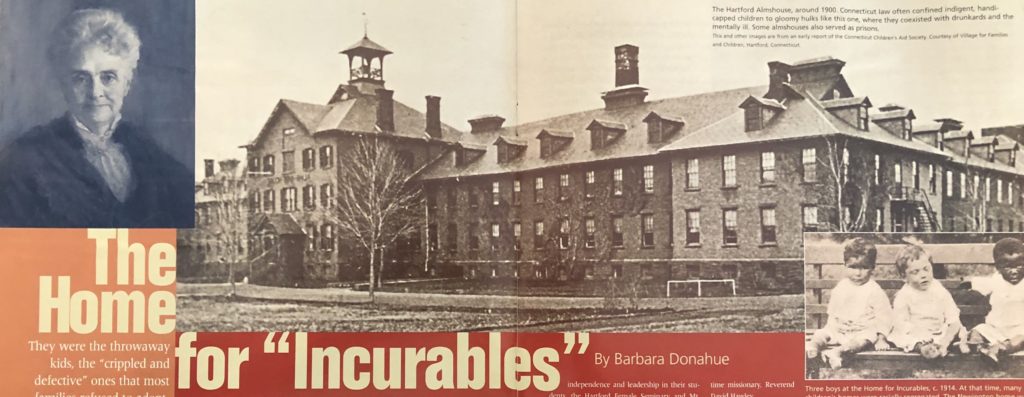

above left: Julia Thrall Smith, portrait by Charles Noel Flagg, private collection. photo: David Stansbury. Center: The Hartford Almshouse, c. 1900, from an early report of the Connecticut Children’s Aid Society. Courtesy of the Village for Families and Children. Below right: Three boys at the Home for Incurables, c. 1914. Courtesy of Village for Families and Children

By Barbara Donahue

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Feb/Mar/Apr 2004

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

They were the throwaway kids, the “crippled and defective” ones that most families refused to adopt, the ones left stranded in town farms and almshouses. But Hartford activist and social reformer Virginia Thrall Smith was passionately determined to give them a home. They appealed, she said “to one’s deepest sympathies with a more than human power.” It took her 16 years of concentrated effort to reach her goal, but she succeeded and in 1898 she opened a “Home for Incurables” in an old farmhouse in Newington. The institution eventually became the Newington Children’s Hospital and now, more than a century later, it is known as Connecticut Children’s Medical Center. It has been a haven, and often a home, for thousands of children.

By New England tradition, each town in 19th-century Connecticut was responsible for its own poor and had to find some way of housing and feeding them. The cheapest solution was to put them in town-run almshouses (also called “town farms” or “poor farms”) whose populations included abandoned old people, habitual drunkards, indigent mothers and their children, and the mentally ill. Some almshouses even did double duty as prisons. They were cheaply run, scant on food and heat, and devoid of comfort. If abandoned or parentless children could not be placed with a local family or sent to a perhaps-distant orphanage, they went to an almshouse. There they were left to bring themselves up as best they could, surrounded by strangers burdened by their own problems. The chances of their reaching adulthood physically and psychologically healthy were slim.

Virginia Thrall Smith was aware of their need. Born in Bloomfield, Connecticut in 1836, she attended two schools that focused on developing independence and leadership in their students, the Hartford Female Seminary and Mt. Holyoke Seminary, later Mt. Holyoke College. Many Victorian schools prepared girls to be little more than ornaments for their husbands’ parlors, but these two institutions offered more intellectual substance and Virginia feasted on it.

At 21 she married William B. Smith, a tailor and clothing merchant, and moved to Hartford. The couple had six children, three of whom died of diphtheria in infancy. Perhaps it was the loss of half her family that compelled her to take on the cause of children who needed an advocate. Whatever her inspiration, she became an energetic social activist as soon as her surviving children were grown. In 1876 she was appointed Hartford City Missionary, succeeding the long time missionary, Reverend David Hawley.

The City Mission, founded in 1859 by the Congregational Churches of Hartford to offer comfort and spiritual guidance to the city’s poor, dispensed material aid as well, and Mrs. Smith quickly expanded the limits of the mission’s work. As expected, she visited and nursed the sick poor and comforted the dying. As not expected, she expanded the mission’s education and recreational work, and by 1878 she had recruited 33 enthusiastic volunteers to manage these projects and help her visit the homebound sick. In the winter of 1880-1881 she opened a free kindergarten and enlisted a board of well-to-do women to support it. Five years later, these women persuaded the Connecticut General Assembly to enact a law establishing kindergartens in public schools throughout the state. It passed without a dissenting vote.

CHILD SAVING

These achievements might have satisfied some reformers, but not Smith. Seeing the environment of poverty as a threat to children’s development, she was determined to take neglected children from their surroundings and place them in clean, wholesome homes. “Child-saving,” as this form of complete removal was termed, became Smith’s passion. In her first three years a city missionary she found new homes for 122 children. Then in 1882, she was appointed to the Connecticut State Board of Charities, assigned to tour the state, inspecting almshouses and poor farms. Smith quickly reported finding more than 2,500 abandoned and neglected children in these dismal shelters. Appalled by her discovery, she went before the Connecticut State Legislature and asked for a law forbidding the commitment of indigent children to such places. A fact-finding commission established that the number of children confined was actually double the number Smith had reported, and in 1883 the state legislature passed “an act to provide temporary homes for the care of dependent and neglected children.” Under this law, each country was required to establish a residence where children would be sheltered until they could be placed with families.

A boon to healthy, adoptable children, the new law specifically excluded from its protection: “Children, demented, idiotic, or suffering from incurable or contagious diseases are not included in this act.” So-called demented and idiotic children were sent to the Connecticut School for the Feeble Minded in Lakeville, but those with physical disabilities were left behind on the poor farms, out of sight and presumably out of mind.

It was a common belief at the time that a disability was a mark of evil, perhaps something inherited from sin buried deep in a family’s past. Children with disabilities were routinely hidden from public view. Virginia Smith vowed to keep them in focus, however. For the next few years, as she and her volunteers continued “child-saving,” she talked constantly of establishing a home for the “incurables,” where children considered ineligible for adoption could find a safe and lasting haven.

In 1891, eight years after passage of the law dictating removal of healthy children from almshouses and poor farms, Smith declared that she herself knew of more than 100 disabled children still confined in these places and increased her efforts to find them a home. However by this time at least one Hartford official was tired of her meddling in what he considered the city’s business. In 1892 First Selectman George W. Fowler publicly accused Smith of “baby farming,” that is, of encouraging young women to have babies whom she could profitably place for adoption. Fowler’s accusation was never proven, but Hartford selectmen were properly shocked, and they let the press know it.

The scandal might have blown away, but the City Mission Board had by then grown weary of supervising charitable works it considered beyond its scope and the tainting of one of these works with a charge of immorality offered a way to return to basics. In December 1892, the Board accepted Virginia Smith’s resignation.

Fortunately, Smith had the friends and the funds to continue. Earlier, some of her supporters had organized as the City Mission Association. Their purpose was to raise funds for the City Mission, and they functioned as its female auxiliary. The Mission accepted the Association’s money but never officially recognized it as part of the organization. Thus, when Virginia severed her connection with the Mission the Association did the same. Its members simply changed the name to The Connecticut Children’s Aid Society and stood ready to assist Smith in “child-saving” and other benevolent work.

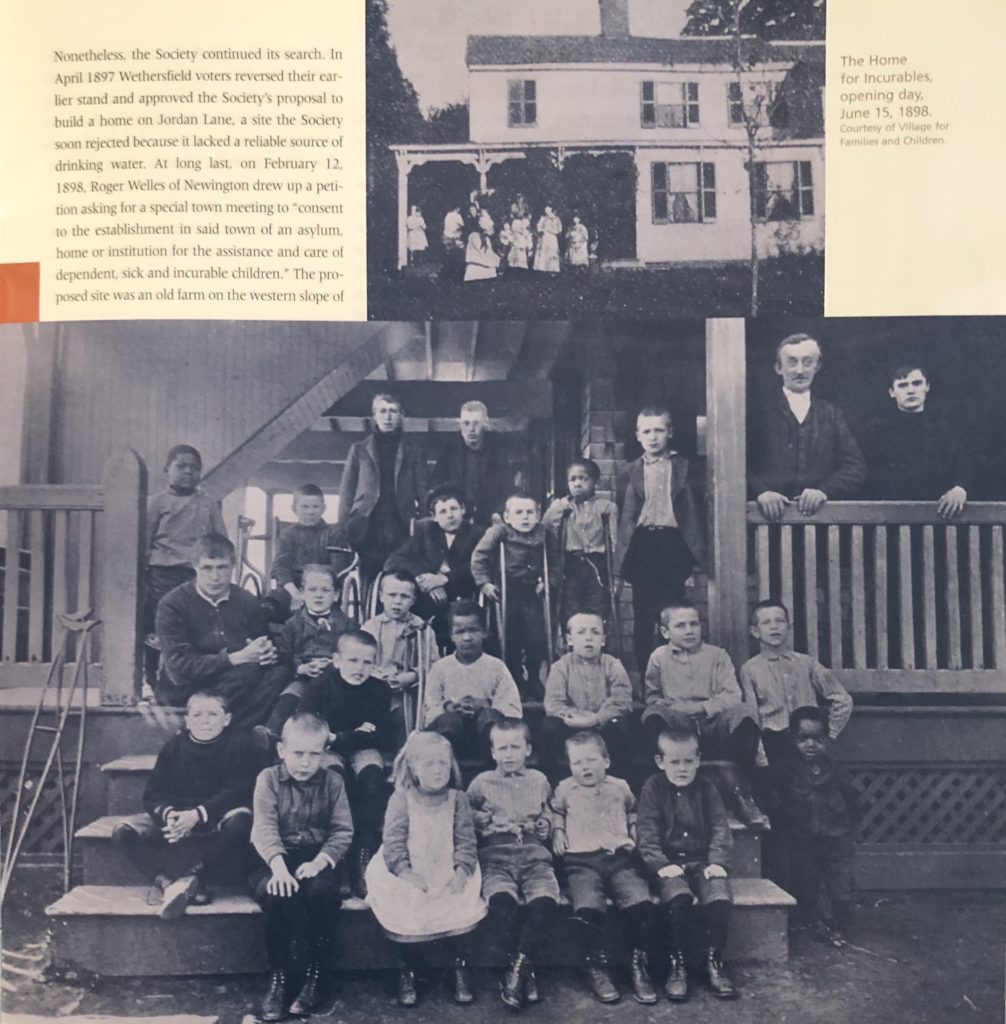

top: The Home for Incurables on opening day, June 15, 1898. Below: Patients on the porch of the Boys’ House, built in 1900, Home for Incurables. Courtesy of Village for Families and Children

OPPOSITION AND SUCCESS

In late 1894 or early 1895 – the records are unclear on the date – Smith and her supporters found a house in Wethersfield, equipped it, and took in three “incurable” children. Wethersfield voters promptly appealed to the state legislature and secured an act that required town approval for the home’s continued presence. At a town meeting held February 28, 1895, they voted to “oppose any and all measures which would allow the establishment of a home for incurable children in the said Town of Wethersfield.” The home closed “at a considerable loss,” and the three children living there were “dismissed,” the Society stated in its 1896 report. (There is no record of where they went.) A year later Plainville voters defeated two successive attempts to establish a home in that town.

The view of such potential neighbors was expressed in a Hartford Daily Times article on January 26, 1897, reporting on the rejection of a third site, this one located on a trolley route in Hartford. “Many persons who use the [trolley]cars,” said the Times, “have a strong objection to this, and their feeling should be respected. Prisoners, drunken men and all whose appearance or condition is painful should be kept off the cars, as far as possible.” The proposed home was to have served only disabled children, but the general public, which found the children’s “appearance or condition” to be “painful,” equated them with prisoners and drunks. This was bigotry with brass knuckles.

Nonetheless, the society continued its search. In April 1897 Wethersfield voters reversed their earlier stand and approved the Society’s proposal to build a home on Jordan Lane, a site the Society soon rejected because it lacked a reliable source of drinking water. At long last, on February 12, 1898, Roger Welles of Newington drew up a petition asking for a special town meeting to “consent to the establishment in said town of an asylum, home or institution for the assistance and care of dependent, sick and incurable children.” The proposed site was an old farm on the western slope of Cedar Mountain. The Newington town meeting approved his proposal and the “incurable” children finally had a home.

The Home for Incurables opened on June 15, 1898 and ten children moved in, with a matron to care for them. In spring 1900, the U.S. Census listed 19 young people as “inmates” in the Home: 8 girls and 11 boys, ranging in age from 2 to 16. Eighteen were white and one was black. All had been born in the United States. Later that year, when representatives of the state Board of Charities visited the home, the “inmate” population had grown to 29. The Board of Charities report noted that the majority of the children were “crippled and defective,” that six had tuberculosis (most likely, non-contagious tuberculosis of the bone) or scrofula (a form of noncontagious tuberculosis located in the lymph glands) and that four suffered from epilepsy. Several youngsters, the investigators stated, would have been better off at the state School for the Feeble Minded in Lakeville. Not all children at the home were homeless. Some of the youngsters, Virginia Smith noted in 1901, “have parents who love them and conscientiously entrust them to our care, paying their support and visiting them frequently, realizing that the home can do better for them considering its advantages of home and school, than could be done in their own homes.” This was not unusual. Even in turn-of-the-century orphanages, less than 20 percent of the children were full orphans. The remainder were children of impoverished parents or of deserted or unmarried mothers, who might reclaim them once they had the means to do so.

Boy in a wheelchair made from a kitchen chair and bicycle parts, c. 1905. Courtesy of Village for Families and Children

From the beginning the home had a board of physicians who served, without pay, as medical advisors. There were eight doctors on the board in 1900. Their involvement must have been largely honorary, as one or another of them visited the home only every other week or so. The doctors’ principal task was to identify “inmates” with infectious diseases and isolate them as needed. The children were, after all, “incurable.”

Occasionally a doctor recommended sending a child to Hartford or New Haven hospitals for surgery or specialized treatment. In 1899 one Newington boy had a leg so badly infected that it required amputation. After surgery, the matron reported that he was “saving his pennies in a bright new bank for a new leg, which has been promised him some day.” A teacher from the home took him to New York, where he was fitted with an artificial leg, apparently there being no source of artificial legs in Hartford. The leg may not have been properly fitted; a month after the child received it, the teacher noticed that it “had not yet begun to feel comfortable.”

A second child described in early records, a 10 year-old boy named Daniel, was badly injured in a train accident. One leg was amputated just below the hip, the other above the ankle. The 1899 report of the Connecticut Children’s Aid Society describes how the society “decided to take up his case, provide him with artificial limbs, and find him some work to do.” Soliciting neighbors in his native Bloomfield, Daniel raised 50 dollars towards the expense; then the Newington staff escorted him to a New York-bound boat, “Free passage having been secured.” When the boat sailed, “He was sitting on deck with his supper in a paper bag, seven dollars in his pocket a note to the doctor.”

Equipped with prostheses, crude as they might have been, Daniel was eventually able to walk, using only a cane. He found work in a restaurant kitchen, attended night school, and looked forward to an office job. Without the society’s assistance he would have remained dependent at his parents’ home.

DAILY LIFE AT THE HOME

Although the children could not hope for cures, they could at least enjoy an environment that was far richer than anything they would have experienced in the almshouses and poor farms from which they had been rescued. There were picnics on Cedar Mountain, occasional trolley rides, and perhaps a summer week or two at the shore. At first, volunteers visited the home twice a week to give what the home’s report described only as “lessons.” Later, full-time teachers joined the staff, set up regular school hours, and supplemented instruction in reading, writing, and arithmetic with nature studies, music, and typing lessons.

The farm on which the home was located was essential to its development, providing clean milk, eggs, potatoes, turnips, beets, apples, and peaches. The children received instruction in house and garden work. Besides providing food for the table and useful work for the children, the farm was a refuge from the dense and dirty city. Since it was located on a steep hillside on the edge of a rural village, there were no close neighbors who might object to the presence of “defective” children.

Some children stayed at the home only a short time. Eight youngsters left in the summer of 1900. Two went to families that voluntarily took them in, four to paid foster homes, and two to their “former caretakers,” whether parents or foster parents is not clear. There is no record of any child being sent back to a poor farm or almshouse. In 1901 Virginia Smith declared, “It is the intention of this Society to give every child in the State, who needs it, a place on this Hillside.” Although the home was open to children throughout the state, no law required town officials to remove handicapped children from almshouses and poor farms and place them, at higher cost, in the Home for Incurables. In August 1903 such a law took effect, enabling local probate courts to order removal and placement in the home. The state pledged $2.50 a week per child; and parent, guardian or town, whichever was responsible for the committed child, paid $1.00 each. Unfortunately Virginia Smith did not live to see this part of her dream enacted as law; she died in January 1903.

Despite state and local aid, expenses consistently outstripped income and each year the home diverted hefty sums from the chief purpose of the Connecticut Children’s Aid Society – placing healthy children for adoption. In time, the diversion caused a rift between the Society and the Home. In 1918 the Home dropped the dispiriting word “incurable” from its name and in 1921 incorporated as the Newington Home for Crippled Children, an organization distinct from the Connecticut Children’s Aid Society. The assets of the Children’s Aid Society were divided, with roughly one third going to the Newington Home. Directors most concerned with the Home resigned amicably from the Children’s Aid Society board and formed a new board. Edith Albin Buck, who had chaired the “home committee of the Children’s Aid Society, became president of the new organization.

As medicines and methods of treatment improved, the one-time “home for incurables” evolved into a full-fledged children’s hospital. Newington became world-famous, particularly for its treatment of orthopedic cases. In 1986 the board of what by then was called Newington Children’s Hospital voted to move to a site adjoining Hartford Hospital, to take advantage of the specialized skills and equipment that proximity to a major hospital could provide. Ten years later the move from the Newington campus was accomplished, and the hospital became Connecticut Children’s Medical Center, an institution where young people are helped in ways Virginia Smith could never have envisioned.

NEWINGTON’S NAMES

Over the years, the hospital has had many names. Each one captured the public view of the institution at the time.

1898: The Home for Incurables

1902: The Virginia Thrall Smith Home for Incurables

1921: The Newington Home for Crippled Children

1947: The Newington Home and Hospital for Crippled Children

1958: The Newington Hospital for Crippled Children

1968: Newington Children’s Hospital

1996: Connecticut Children’s Medical Center

This article is adapted from They Called It “the Home for Incurables,” by Barbara Donahue, published in 2004 by the Connecticut Children’s Medical Center. Unless otherwise noted, all quotations are taken from early annual reports of the Connecticut Children’s Aid Society (now known as the Village for Families and Children).

Barbara Donahue has written histories of the town of Farmington, Miss Porter’s School, the Hospital for Special Care (New Britain), the Amistad rebellion, and other local topics.

EXPLORE!

Read more stories about Childhood and Health & Medical history on our TOPICS pages.

Subscribe to receive every issue!