The Stratford Civil War monument, cast by Monumental Bronze Company in Bridgeport, 1889. The monument, which is more than 35 feet tall, began to lean; stress caused seams to separate. An internal steel framework was installed in 1986 – 1987 to support the monument. photo: Carolyn Ivanoff

By Carolyn Ivanoff

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The great age of American monumentation began after the Civil War and continued into the early 20th century, as Matthew Warshauer and Mary Donohue note in “Memorials to a Nation Preserved” (CT Explored, Spring 2011). During this period the national demand for personal and public monuments seemed endless. There was a robust American market for monuments to famous people and citizen soldiers and for public and private funerary memorials. In response to this demand, as George C. Waldo Jr. notes in History of Bridgeport and Vicinity (S. J. Clarke Publishing, 1917), Bridgeport’s Monumental Bronze Company, founded in 1874, became a distinctive and exclusive purveyor of cast monuments and tombstones. Often affectionately called “zinkies” by cemetery aficionados today, these metal markers were a remarkable example of American manufacturing and ingenuity. Monumental Bronze Company was a true American original. Its legacy is preserved and readily visible in cemeteries and statues nationwide.

The industrial powerhouse that was Bridgeport, Connecticut during the 19th and 20th centuries made its mark internationally with many, many products. Bridgeport factories manufactured everything from sewing machines, cars, phonographs, typewriters, and corsets to submarines, machine tools, and munitions, and more. Among these factories, the Monumental Bronze Company, on the corner of Howard and Cherry streets, filled an exclusive and distinctive place in American manufacturing. It was the only company in the nation that cast metal tombstones and memorials from a substance it called “White Bronze.” Every marker was made to order and, therefore, was one of a kind. The company also cast numerous Civil War monuments that can be seen in cemeteries, on town greens, and on courthouse squares of many states, North and South.

Samuel Orcutt, in his 1886 A History of the Old Town of Stratford and the City of Bridgeport Connecticut, Part II, tells of the founding of the company. In 1868 M. A. Richardson, superintendent of a cemetery in Chautauqua County, New York, began searching for a substance more durable than stone for monument use. He experimented with various materials including stained glass and galvanized iron, none of which he found suitable. He stumbled upon and was struck by the qualities of cast or molded zinc. After several attempts, partners, and failed investments, he sold his interests to Wilson, Parsons and Company of Bridgeport in 1874. In 1879 the company was formed into a stock company and renamed the Monumental Bronze Company.

Monumental Bronze Company advertised products made of “White Bronze”—but in fact, the metal contained no bronze at all. The material was almost pure zinc alloyed with tin, but as Barbara Rotundo discusses in her essay about the company in Cemeteries and Grave Markers: Voices of American Culture (UMI Research Press, 1989), “White Bronze” sounded so much more elegant and sophisticated than zinc and the name made monuments more marketable.

John Benson, 29th Colored Regiment Volunteers, marker (front and back), Putney Cemetery, Stratford. The marker was chosen directly from the 1882 Monumental Bronze sales catalog. photo: Carolyn Ivanoff

Monuments could measure a few inches, a few feet, or be quite imposing in height. The monument casts were made from wax and plaster pressed into sand molds. Molten zinc was poured into the molds. The process created panels that were fused together and assembled into a finished monument. More molten zinc sealed the seams, and decorative screws held the panels onto the monument. The completed monument was then sandblasted to fashion a granular stone-like look and lacquered with a secret formula that chemically oxidized the metal to create a distinct blue-gray patina. White bronze does not rust or wear and never needs painting. For these reasons white bronze monuments are a genealogist’s dream. Their cast panels, letters, and dates are easily read, as they remain as crisp and clear as on the day of their installation.

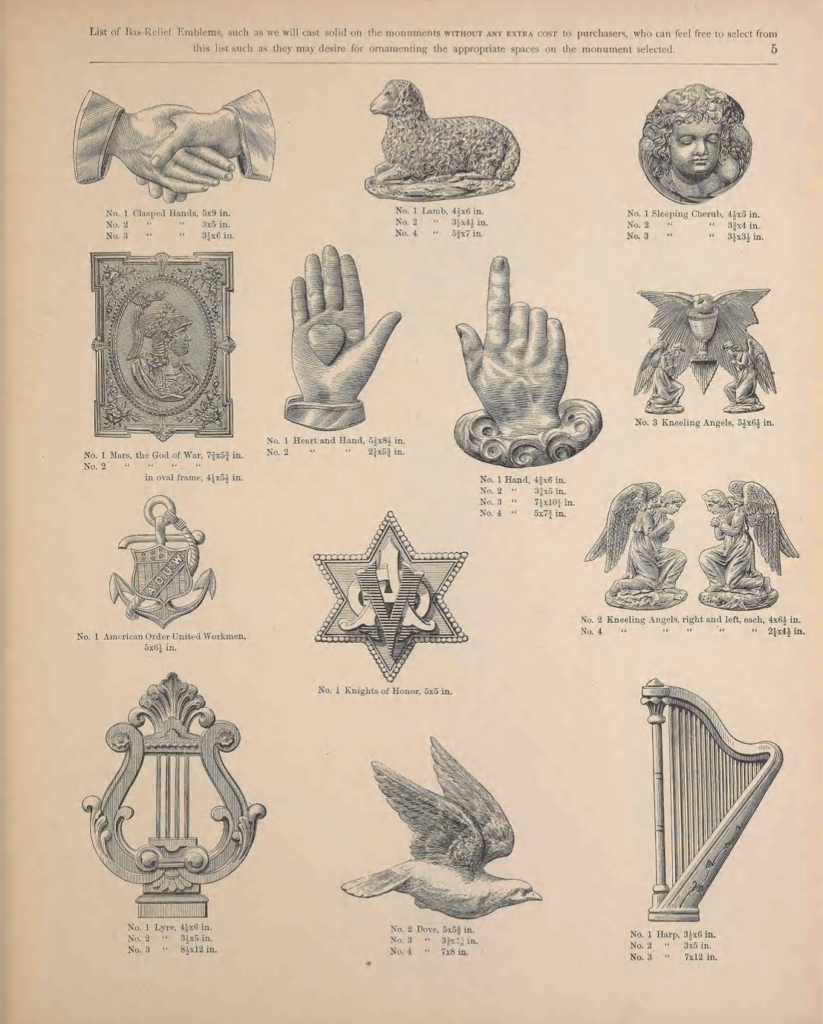

Page showing bas relief designs available to customers to customize a monument, Catalogue of the Monumental Bronze Co., October 1882.

Rotundo described the sales process. The company had no showroom. Monuments were sold by traveling salesmen from extensive catalogs and could be ordered from anywhere in the nation. The castings were all made in Bridgeport and shipped to the desired location where they were assembled. To facilitate the process the company founded subsidiaries in Chicago, Des Moines, New Orleans, and Canada.

The company’s promotional materials were compelling, as its pamphlets, catalogs, and newspaper advertisements attest. Consumers could save money, the materials asserted, and get a more artistic design and a more enduring monument than they would with any type of stone. The advertising also claimed white bronze was maintenance free. The company claimed that no cracking or crumbling would occur.

Buyers could design the base, central monument, a topper, and a statue, or they could mix and match many of the standard catalog pieces, choosing among a variety of shapes, sizes, medallions, portraits, busts, and symbolic images. Words, names, dates, sayings, and prayers could be cast in infinite variety.

This level of customization and personalization got the company into at least one public relations mess. On May 14, 1890, The Meriden Journal blasted Monumental Bronze for accepting a private commission. Under the headline “Monumental Blasphemy,” the paper wrote:

The Monumental Bronze Company of Bridgeport is making for an ex-liquor dealer in Kenosha, Wisconsin, a monument on which is placed numerous inscriptions, many of which are absolutely blasphemous, the mildest among them being: ‘Erected by L. Knapp, an unwavering adherent to science, philosophy, history, and sound logic; discarding all ancient and modern humbug religions; a truly died-in-the-wool[sic]infidel to all priestly orthodoxy. I am a bold, champion sinner, compete with me anyone who will, I will lie, cheat, steal, rob and murder and do all damnable deeds—that I will. Only ceasing in time to get sorry and will settle the bill.’

The Monumental Bronze Company advertised opposite stone and granite companies in newspapers. The company and its local competitor, Chas. J. Hughes Stratford Granite and Marble Works, often ran advertisements side by side in Fairfield County papers. Sometimes the Monumental Bronze ad was on top, and sometimes Stratford Granite and Stone’s ad was on top. Often the ads appear to be conjoined. Monumental Bronze never missed the opportunity to remind prospective customers that they could save money with its product and that white bronze was more enduring than any stone. Its ads emphasized its longevity with advertising copy such as “monuments are not erected for a generation but for all time,” “White Bronze is as enduring as the pyramids,” “When stone has crumbled into dust, White Bronze will stand intact,” and “More artistic and expressive than stone and less expensive.”

4th Ohio Monument, Gettysburg National Battlefield, Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. photo: Carolyn Ivanoff

A significant and public part of the Monumental Bronze Company’s business went to memorializing the Civil War. Many of the memorials were not to great men but honored the sacrifices of the common soldier. Many of these men, and their loss, were remembered personally by families and neighbors in small towns across the reunited nation. A company catalog promoted statuary that was suitable for both North and South. One brochure featured the elaborate Civil War memorial erected by the company in Stratford, Connecticut in 1889. The figure of a standard bearer with a drawn sword, protecting the flag, is 35 feet tall. The base, pedestal, and figure are all cast white bronze. The Stratford monument is the only large-scale white bronze monument in Connecticut. Smaller funerary monuments to individual soldiers can also be found in cemeteries around the state.

The stock-in-trade Monumental Bronze Civil War memorial featured the figure sometimes referred to as the “Silent Sentinel,” or what the company catalog called simply “an American Soldier,” a mustached soldier in a greatcoat at parade rest with both hands around the barrel of his rifle. The bluish-gray color of the white bronze could conveniently represent the uniform of either North or South. By 1898, though, memorials for the South began to be cast with a slouch hat and a short shell jacket rather than the Union soldier’s kepi, great coat, and knapsack.

To commemorate its sacrifice on the battlefield at Gettysburg, the 4th Ohio Volunteer Regiment ordered a monument from Monumental Bronze, installed on September 14, 1887. The company provided the regiment with the “Silent Sentinel” figure at the top of an ornate, custom white bronze pedestal. Pedestals could also be of granite or marble, but the Ohio veterans went all in for a complete white bronze monument. The 4th Ohio also chose to have the Monumental Bronze Company cast flank markers and a smaller monument to Companies G and I along Gettysburg’s Emmitsburg Road. The smaller monument was chosen from the standard monument catalog.

The company’s monuments weathered well over the years, but they did not prove to be quite as “enduring as the pyramids.” Zinc is brittle, and after more than 100 years the most common problem for many monuments is breakage, especially on surface castings. Thinner castings are also easily dented.

Smaller monuments have proven to be quite stable and durable, though. The biggest threat to smaller funerary monuments is vandals smashing in or detaching the panels. Stories abounded of cemetery grounds keepers unscrewing panels to larger monuments to store landscaping tools. Urban legend holds that bootleggers and criminals would enter cemeteries at night to stash their illegal booze or ill-gotten gains inside the hollow white bronze monuments by unscrewing the panels, as Rotundo reported.

Over time the larger, more elaborate monuments are subject to “metal creep,” especially if the pedestals were also cast white bronze and not stone, as Rotundo documents. The Stratford Civil War memorial and the 4th Ohio monument at Gettysburg are prime examples. These tall monuments required extensive restoration after they began to lean, or “creep.” This condition is caused by the weight of the monument bearing down on the base, which then begins to bow and bulge, list and lean. Ultimately the seams of the base crack and separate due to stress. This slow aging process requires that the hollow monuments undergo extensive restoration by placing a steel support structure inside to support the weight. One of the biggest threats to white bronze memorials was that early restorations involved filling the hollow monuments with cement, which only caused more damage to the structure.

At the beginning of the 20th century the demand for white bronze monuments began to diminish. Stone companies became more aggressive in their marketing against “white bronze.” “Metal creep,” evident in larger monuments, provided them with marketing ammunition to exploit a major weaknesses of white bronze. Granite and stone companies were successful in influencing cemeteries to ban white bronze monuments due to this occurrence of “metal creep.” After the installation of the 4th Ohio monument at Gettysburg, white bronze monuments were banned there for that reason, as noted on Gettysburg.stonesentinels.com. The New Milford Center Cemetery Association, in a letter to the editor in the Newtown Bee on September 18, 1908, announced that “memorial work of monumental bronze or similar materials” was banned from the new Treadwell cemetery addition.

Monumental Bronze Company manufactured made-to-order monuments and markers from 1873 until 1914. In 1914, as World War I got underway in Europe, the U.S. Government began to take control of metal markets, including zinc, to put the nation on a wartime production footing. It took over the Monumental Bronze Company to manufacture gun mounts. Though it no longer produced monuments, the company continued to manufacture custom cast panels to update existing grave markers until it went out of business in 1939. Though World War I disruptions were a factor, Rotundo believed it was ultimately decreasing consumer demand in the early 20th century that led to the demise of the remarkable, and uniquely American, Monumental Bronze Company.

As I proceed into my post-middle-age years, I begin to feel like the monumental bronze monuments I adore. I am experiencing “the creep.” The settling and spreading of age is apparent as my weight bears down and I begin to bow and bulge. I often contemplate what, if anything, will mark my former existence when I am gone. I am sorry I cannot order a Monumental Bronze marker for myself. I would dearly love a unique artifact from the city of my birth that I could have cast and assembled to my taste to mark the last place on earth for me. I would dearly love to be ever remembered in monumental bronze. I would so dearly love a zinkie!

Carolyn Ivanoff is an independent historian. This story is based on “Monuments Everlasting – Bridgeport’s Monumental Bronze Company,” bportlibrary.org. She last wrote “Fame and Infamy for the Hulls of Derby,” Summer 2012. Her book, We Fought at Gettysburg, is forthcoming in Spring 2022.

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SPRING 2022 CONTENTS

LISTEN!

135. Zinc Gravestones – Bridgeport’s Monumental Bronze Company

Assistant Publisher Mary Donohue explores the history of the Monumental Bronze Company with our author Carolyn Ivanoff.