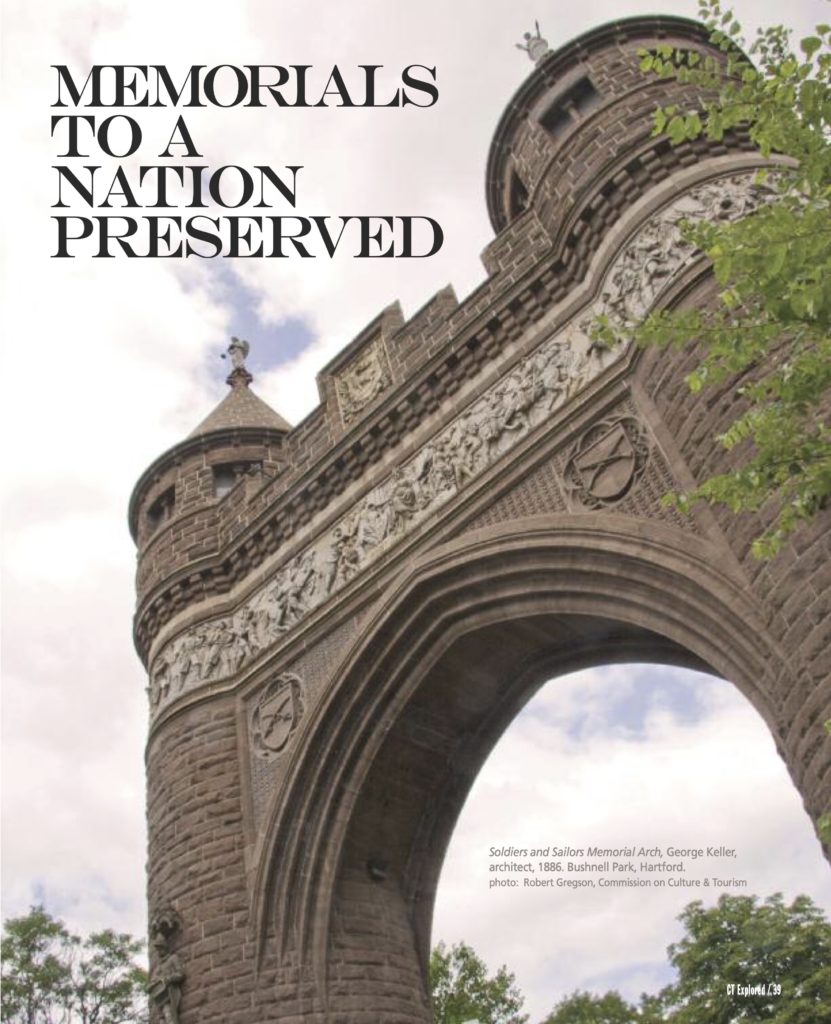

Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch, George Keller, architect, 1886. Bushnell Park, Hartford.

photo: Robert Gregson, Commission on Culture & Tourism

By Matthew Warshauer and Mary M. Donohue

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The Civil War has been memorialized more than any other conflict in America’s history. As historian Drew Gilpin Faust poignantly noted in This Republic of Suffering: Death and the American Civil War (Vintage, 2008), “The impact and meaning of the war’s death toll went beyond the sheer numbers who died. Death’s significance for the Civil War generation arose as well from its violation of prevailing assumptions about life’s proper end—about who should die, when and where, and under what circumstances.” The public was forced to mourn the dead on a massive scale, and the resulting memorializing and monument building, Faust asserts, was unrivaled in the nation’s history. This was new, as the democratic revolutionaries who won independence for this country had an initial distaste for monuments, thinking them the province of monarchies or papists.

Battlefields were among America’s first national memorials. The bloodshed, suffering, and death of warfare were so profound that the ground on which they occurred was quickly deemed hallowed. President Lincoln visited Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on November 19, 1863 in the immediate aftermath of the great battle that had taken place there and announced solemnly, “We have come to dedicate a portion of that field, as a final resting place for those who here gave their lives that the nation might live. It is altogether fitting and proper that we should do this.” Just a month later, Fred Lucas, from Litchfield and a soldier in the 2nd Connecticut Heavy Artillery, witnessed the birth of another piece of sacred ground, Arlington Cemetery in Virginia, while serving in the defenses outside of Washington, D. C. He wrote home in December 1863: “This is a beautiful ground and is kept up in elegant style by the government. It already contains thousands of graves. It will doubtless be one of the memorable places connected with this rebellion, noted as is Gettysburg; and a place to be visited by travelers as well as relatives of the brave men who sleep there.” Thus, even when the Civil War was at its height and the final outcome was unknown, people believed that the great sacrifices of the war and the men who fought deserved to be honored and remembered.

In Connecticut and other states where no battles were fought, war memorials and monuments began to spring up when the war ended. Typically erected through the commitment of a group of veterans or families of veterans, these tributes were the joint effort of donors, patrons, politicians, municipal boards, citizen commissions, veterans, artists, and architects and involved a complex process. The monument committee might contact a sculptor, manufacturer, or architect, or the committee or public body might hold a competition. Competitions had the benefit of providing the committee with a range of styles, prices, and design solutions at little or no initial cost to the committee. Sometimes, the project’s architect commissioned a sculptor directly.

As people across the nation grappled with how best to commemorate the war, the demand for public war monuments helped to create an industry in Connecticut. Connecticut’s numerous stone quarries, stone yards, and metal casting companies began to produce public monuments for sites across the country.

In Hartford, this industry was promoted by businessmen such as James G. Batterson (1823-1901). In addition to establishing, in 1864, the Travelers Insurance Company, of which he was president, he was the owner of a cemetery monument company. A dealer and importer of stone, Batterson employed Carl Conrads (1839-1920), a German sculptor, to design sculptures, and George Keller (1842-1935), an Irish-born architect, to design their bases. Their work can be seen at the national battlefield parks in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania and Antietam, Maryland.

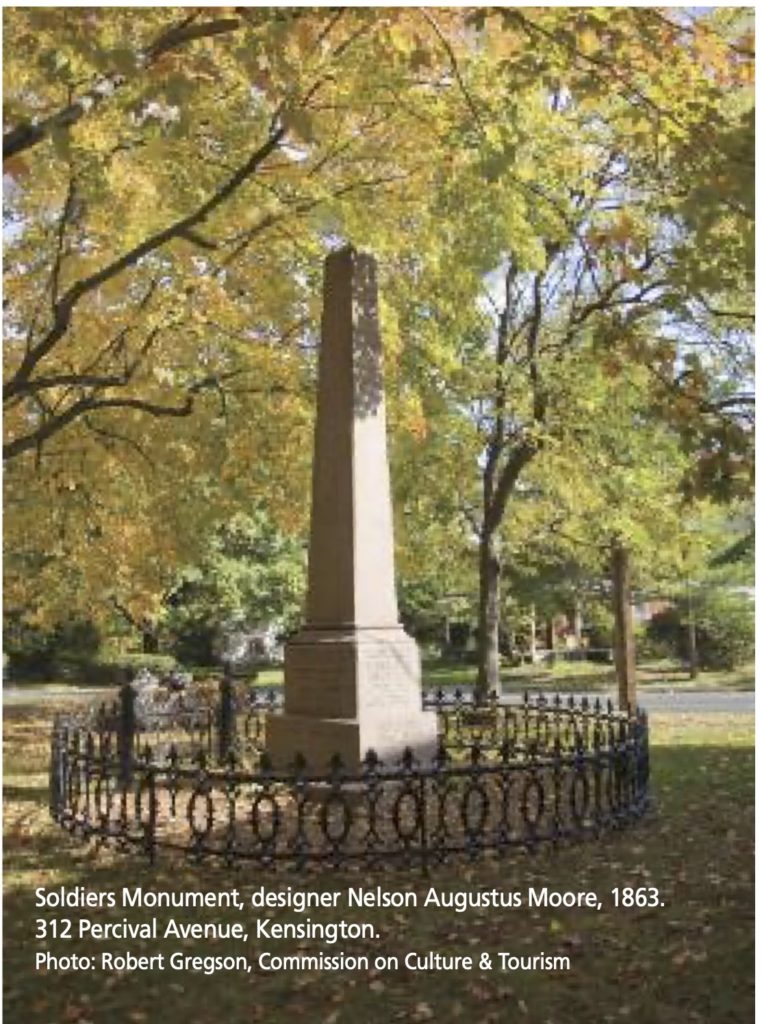

Soldiers Monument, designer Nelson Augustus Moore, 1863. 312 Percival Avenue, Kensington.

Photo: Robert Gregson, Commission on Culture & Tourism

On July 28, 1863—four months before President Lincoln dedicated the Gettysburg memorial and before the war had even ended, Kensington, Connecticut dedicated not only the state’s but the North’s first Civil War monument. The town had lost six men in the first two years of the war, and Reverend Charles B. Hilliard of the town’s Congregational Church, himself an ardent supporter of the war, initiated a movement to create the memorial. The 20-foot-high stone obelisk was carved from brownstone quarried in Portland, Connecticut. The Soldiers Monument included the seal and motto of Connecticut, “Qui Transtulit Sustinet,” (“He Who Transplants Still Sustains”). The names of the deceased soldiers and a simple message to remember those who had fallen were also inscribed in the stone:

Erected to commemorate the death

of those who perished in suppressing

the southern rebellion

“how sleep the brave who sink to rest

by all their country’s wishes bless”

left: Soldiers Monument, designer James G. Batterson, 1866, West Cemetery, Bristol. right: Civil War Monument, designer Robert W. Wright, 1866. 111 Church Drive, Cheshire. photos: Matthew Warshauer

The next monuments erected in Connecticut came in the war’s immediate aftermath. In 1866, four towns—Bristol, North Branford, Cheshire, and Northfield in Litchfield—dedicated obelisks to the memory of those who died. The Bristol Soldiers Monument, in keeping with the theme of honoring the dead, was placed on the highest hill in the West Cemetery. The monument was made of Portland brownstone supplied by Batterson; the obelisk was crowned with a large carved eagle, the traditional symbol of American nationalism. The names of the deceased solders were inscribed on the shaft, along with the battles in which they died, and an inscription noting that the monument was erected in “grateful remembrance” and that “the sacrifice was not in vain.” The Soldiers’ Monument in North Branford, located on the town green, was simpler in design, with no crowning features, though it offered more details about the memorialized soldiers, including their names, units, place of death, and ages. The Cheshire obelisk, “erected to the memory of those who enlisted,” was similarly simple in design and again located on the town green. It was unusual for early monuments in that it included the names “Lincoln” and “Foote” (Admiral Andrew Foote, born in New Haven) on the pedestal. Originally, it listed only the names of 14 men who had died, but in 1916, all town men who had served were included. The Northfield monument had a finial at the top, out of which protruded a flame. It too included Lincoln’s name, as well those of the soldiers who perished, with an inscription that read, “that the generations to come might know them.”

These early monuments represent the overarching themes of the many memorials to be built over the coming decades. David Ransom’s pioneering 1993 study published by the Connecticut Historical Society investigated some 136 monuments in the state, virtually all of which were built between the end of the war and the 1920s. Ransom notes that as early as 1867-1868, monument designers had already moved away from the traditional funeral obelisk and placement in or near cemeteries or churches to designs and locations such as near town hall, on the town green or in city parks that more pointedly honored soldiers’ service, not just their memories. The vast majority continued to use words such as “memory,” “tribute,” “honor,” and “gratitude” or “grateful recognition.” Very few of the structures, even into the 20th century, referred to the war as the “Civil War.” Rather, they mentioned “the War of Rebellion” or “the War for the Union” and noted that the men had fought in “Defense of the Union” or to “Preserve the Nation,” or, echoing Lincoln’s words in the Gettysburg Address, asserted that the “brave men who gave up their lives that the republic might live.”

“Freed Slave” from the

Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch, Albert Entress, sculptor, 1886. Bushnell Park, Hartford. photo: Robert Gregson, Commission on Culture & Tourism

Certainly the best-known monument in Connecticut is the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch in Hartford’s Bushnell Park. Designed by architect George Keller, it was completed in 1886 and was the first triumphal arch in the United States. It will celebrate its 125th anniversary on Saturday, September 17, 2011, with all the fanfare due a memorial of its significance. It is the state’s largest freestanding Civil War memorial, standing at 116 feet tall; each of the two towers is 67 feet in circumference. Keller attempted to tell the story of the war and its commemoration in terra cotta friezes by sculptors Samuel Kitson (north frieze) and Caspar Buberl (south). The friezes include almost 100 life-size figures representing the many citizens of Hartford who went to war. The structure also features six statues by Hartford sculptor Albert Entress (1846-1926) depicting a farmer, blacksmith, student, carpenter, and mason: the “common” men who dropped the tools of their trade and raised a rifle. The sixth statue, originally to represent a merchant, was changed at the last minute and replaced with a slave, his shackles broken, holding a slate on which the alphabet is written, representing the educational uplift of his race.

The inclusion of the slave makes an interesting statement, as few people in the North, and certainly in Connecticut, entered the war to emancipate slaves. The vast majority of Connecticut’s residents were not abolitionists. They supported the war to preserve the Union. The state’s Civil War monuments are instructive in this regard. Only three (the Soldiers and Sailors Memorial Arch in Hartford, the Waterbury Soldiers’ Monument (1884), and the Connecticut Twenty-Ninth Colored Regiment C.V. Memorial in New Haven (2008)) make any reference to race or slavery.

Monuments throughout the state were dedicated with solemn ceremonies at which thousands, sometimes tens of thousands, gathered. The belief that the soldiers’ sacrifice and suffering was not in vain was reiterated at dedication ceremonies and annual decoration days at which flowers were placed on the graves of the Civil War dead.

The most sought-after speaker at dedication events was war hero General Joseph R. Hawley, a man who epitomized devotion to the Union. He had marched out of the Hartford Evening Press office, where he was editor, the moment news arrived of the firing on Fort Sumter and helped organize the 1st Connecticut Regiment. He then reenlisted in the 7th once his initial term of duty ended; he served throughout the entirety of the war, sometimes coming home to enlist more troops, acquire supplies for his men, or help to rally an often dissent-ridden Republican Party. He was elected governor of Connecticut in 1866 and went on to become a U.S. representative and senator.

Hawley’s patriotism knew no limits. He once announced, “I believe in the Fourth of July all over, from the crown of my head to the sole of my feet … I believe in the flag.” He was equally devoted to his home state: “I have no sovereign but Connecticut and Uncle Sam,” he proclaimed; he felt that “Connecticut had the proudest history in the world.” In dedication speeches, such as one in Manchester in 1872, Hawley told crowds how Europeans claimed the United States “had no history,” but that the Civil War had provided an even “nobler history” than the Old World could claim. The nostalgic storyteller loved to talk about the state’s patriotic past. At Hartford’s Memorial Arch dedication, he took the crowd all the way back to Thomas Hooker and the Fundamental Orders, which he saw as Connecticut’s great contribution to free government.

Erection of memorials to the Civil War continued into the 20th century. Five monuments were created during the 50th anniversary of the war (1911-1915). The most significant was Yale University’s 1915 Memorial (Woolsey) Hall Rotunda, a marble hallway carved with the names of men who had attended the university and who had fought in the war, whether for the Confederacy or for the Union. The message reads, “that their high devotion may LIVE IN all her sons and that the bonds which now unite the land may endure.” The message was about reconciliation, as was the entirety of the 50th anniversary.

Connecticut 29th Colored Regiment Connecticut Volunteers Memorial, Ed Hamilton, sculptor, 2008. Criscuolo Park, New Haven.

photo: Robert Gregson, Commission on Culture & Tourism

African Americans and Irish Americans, groups that were economically disadvantaged and marginalized by the state’s upper classes in the 1860s, served the Union cause loyally in Connecticut regiments. The state’s newest monuments, both dedicated in 2008, memorialize the Twenty-Ninth Colored Regiment (New Haven) and Connecticut’s Ninth “Irish” Regiment (Vicksburg National Military Park, Mississippi). And new monuments are being planned. The Shelton Civil War Monument, Inc. is currently accepting donations to create a memorial in that town, a testament to the extent to which some in Connecticut remain connected to the Civil War.

Connecticut’s Civil War monuments are our most tangible legacy of a generation that dedicated itself to preservation of our nation. They were an attempt by those who lived through the nation’s greatest struggle to make sense of the death and suffering that occurred on such a massive scale. Those who lived through the war wanted future generations to understand and to remember. These memorials are spread throughout Connecticut, and once aware of them, readers will be amazed at the degree to which they now “pop” out everywhere.

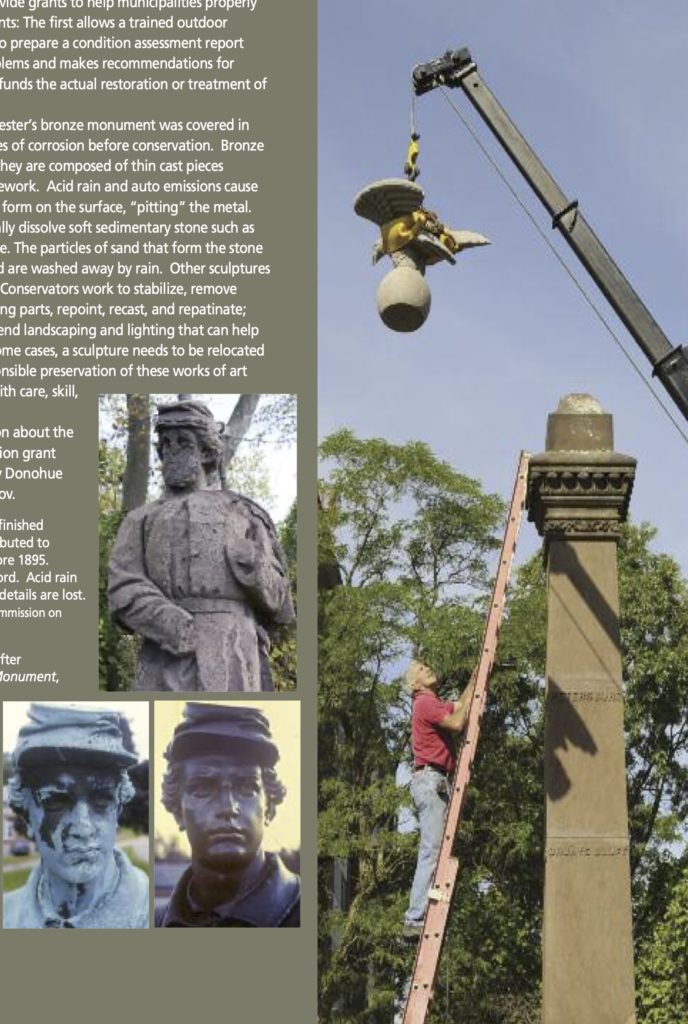

left, top: Forlorn Soldier, unfinished brownstone figure, attributed to James G. Batterson, before 1895. 119 Airport Road, Hartford. Acid rain dissolves the stone, and details are lost. photo: Robert Gregson, Commission on Culture & Tourism; below left: Before and after restoration of Soldiers Monument, James G. Batterson, Carl Conrads, sculptor, 1876. Center Park, Manchester. Surface corrosion was removed and the bronze surface repatinated and waxed, revealing the sculptor’s original artistic vision. photos: Francis Miller, Conserve Art LLC.; right: eplicated brownstone eagle being placed on top of the Soldiers Monument, attributed to James G. Batterson, 1868. Center Cemetery, East Hartford. photo: Town of East Hartford

A Monumental Legacy at Risk

Monuments’ illusion of permanence is deceptive. They are in fact threatened by weather, pollution, vandalism, and neglect, and by ill-informed attempts to clean them. Civil War monuments are pieces of art and should be restored by a trained outdoor sculpture conservator. The Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism has two programs that provide grants to help municipalities properly care for their monuments: the first allows a trained outdoor sculpture conservator to prepare a condition assessment report that identifies the problems and makes recommendations for treatment; the second funds the actual restoration or treatment of the sculpture.

The Town of Manchester’s bronze monument was covered in green and black patches of corrosion before conservation. Bronze statues are not solid—they are composed of thin cast pieces assembled over a framework. Acid rain and auto emissions cause damaging corrosion to form on the surface, “pitting” the metal. Acid rain will also literally dissolve soft sedimentary stone such as marble and brownstone. The particles of sand that form the stone become “unglued” and are washed away by rain. Other sculptures suffer from vandalism. Conservators work to stabilize, remove corrosion, replace missing parts, repoint, recast, and repatinate; they also may recommend landscaping and lighting that can help protect the piece. In some cases, a sculpture needs to be relocated if it is to survive. Responsible preservation of these works of art must be approached with care, skill, and training.

For more information about the state historic preservation grant programs contact the State Historic Preservation Office at portal.ct.gov/DECD/services/historic-preservation.

Matthew Warshauer, Ph.D., is a professor of history at Central Connecticut State University and co-chair of the Connecticut Civil War Commemoration Commission. Mary M. Donohue is the senior architectural historian and survey and grants director of the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism.

Explore!

There are approximately 140 Civil War memorials in the state. The Smithsonian Art Museum’s Inventory of American Sculpture includes all of Connecticut’s Civil War monuments in its on-line database at http://sirismm.si.edu/siris/ariquickstart.htm. Each piece is represented there with a thumbnail photo, short listing, and full description. The SIRIS database allows you sort by artist, foundry, location, and subject, so you can, for example, search for all the Connecticut brownstone monuments or all the pieces by Batterson.

Three to Visit:

Soldier’s Monument, 312 Percival Avenue at Sheldon Street, in the Kensington section of Berlin. New England’s first, constructed even before the war ended.

Soldiers & Sailors Memorial Arch, Ford Street, Bushnell Park, Hartford. For information on tours offered by the Bushnell Park Foundation Thursdays, noon – 1:30 from May to October visit www.bushnellpark.org.

Andersonville Boy and the Petersburg Express (a 13-inch mortar used in the siege of Petersburg, Virginia), Connecticut State Capitol grounds, 210 Capitol Avenue, Hartford; also see the Civil War Battle Flag Collection in the West Wing of the State Capitol.

Read more about Connecticut in the Civil War:

Spring 2011

Winter 2012/2013

our Connecticut in the Civil War TOPICS page

And more about Connecticut at war on our War Stories TOPICS page