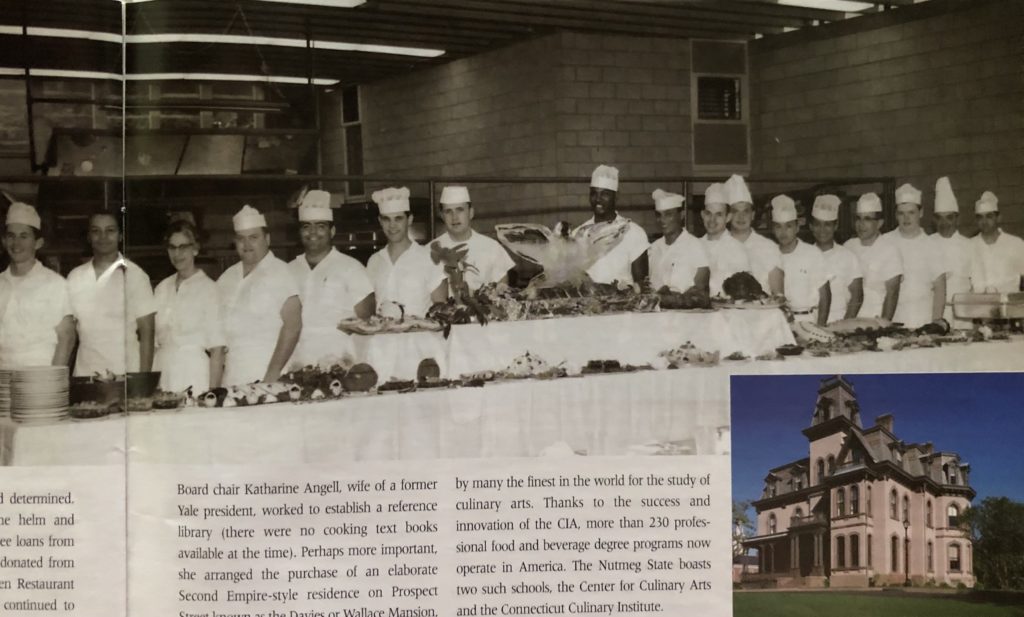

top: students in a buffet class, c. 1960 – 1963. Culinary Institute of America. right: The Betts House where the New Haven Restaurant Institute was housed from 1947 – 1972. photo: Michael Marsland, Yale University

By Susan Chandler

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2007

Every profession has its leadership institution. The performing arts have Juilliard, the military has West Point and the culinary arts has the CIA. – Craig Claiborne

If the business of making meals is not the oldest profession, then it must be the second. As soon as society developed sufficiently to allow for specialization of labor, you can be sure that whoever served up the tastiest stew was quickly singled out as “cook.” But it wasn’t until 1895 that Le Cordon Bleu was established to professionally train chefs. And while it makes perfect sense that Europe’s first internationally respected culinary school was located in Paris, it is more surprising to learn that America’s was founded not in New York, Chicago, or San Francisco, but in New Haven.

The year was 1944. With World War II still raging, M. Charles Rovetti, the executive secretary for the New Haven Restaurant Association, suggested to its president, Richard Dargan, that a cooking school was needed to address the severe shortage of trained professionals. One year later, a small storefront was secured, but someone was needed to run the school.

For director, Dargan made a somewhat startling choice. Frances Roth was the first female member of the Connecticut Bar Association, a former assistant district attorney and assistant city prosecutor, and an outspoken advocate for “decency.” she was also, as it turns out, exactly the powerhouse needed to get the ovens fired up and students cooking. Roth was well connected, enthusiastic, and determined. With a respected director at the helm and $12,700 in short-term, interest-free loans from local restaurants and appliances donated from utility companies, the New Haven Restaurant Institute was on its way. Roth continued to practice law and teach at Yale when she started as director; having made her mark in law, though, she gave that career up when leading the school became a full-time endeavor.

Frances Roth, first female member of the Connecticut Bar Association, former assistant district attorney and assistant city prosecutor, became the first director of the newly-created New Haven Restaurant Institute, later the Culinary Institute of America, c. 1957 – 1960. Culinary Institute of America

The timing could not have been more fortuitous as the war drew to a close. The passage of the Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944, better known as the G.I. Bill, changed the face of education in America. Post-secondary schools of every kind experienced unprecedented popularity. And, indeed, former soldiers seemed to know that even civilians march on their stomachs. The inaugural class of 16 at the institute was composed entirely of veterans. Faculty for the eight-month, 78-menu course was limited to a chef, a baker, and a dietician. Applications for the second class of 1946 quickly swelled to 55. The school had begun to outgrow its facility before the first finger was burned.

Board chair Katharine Angell, wife of a former Yale president, worked to establish a reference library (there were no cooking text books available at the time). Perhaps more important, she arranged the purchase of an elaborate Second Empire-style residence on Prospect Street known as the Davies or Wallace Mansion, designed by noted architect Henry Austin with 34 rooms on a five-acre site with two outbuildings. The school would move there in 1947.

Just four years after the school was established, Look magazine featured Roth as she addressed the National Restaurant Association in Chicago promoting “The Culinary Institute of America,” as it would soon be called, as the premier professional cooking center in the country. And it was.

With growing enrollment and prestige, the need for larger and more appropriately “collegiate” quarters led to the institute’s relocation to a former Jesuit seminary in Hyde Park, New York, in 1972.

From its origins as the first vocational school of its kind in the United States, the CIA has evolved into an accredited four-year college considered by many the finest in the world for the study of culinary arts. Thanks to the success and innovation of the CIA, more than 230 professional food and beverage degree programs now operate in America. Connecticut boasts two such schools, the Center for Culinary Arts and the Connecticut Culinary Institute.

The Davies Mansion suffered a severe fire in 1990. It is now fully restored (as the Betts House) and now houses the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization.

Susan Chandler is the historical architect with the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism and a food and wine enthusiast. She last wrote about the Slow Food movement in the Spring 2006 issue.

Explore!

“America’s First Cookbook,” Spring 2006

Read all of our stories about historic foodways on our TOPICS page.

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!