by Jennifer LaRue SPRING 2006

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

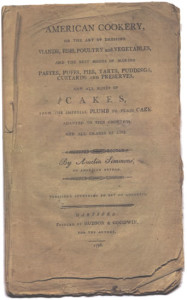

Two centuries before Jacques Pepin became Connecticut’s most famous chef, Amelia Simmons made culinary history by publishing, in Hartford, what is now widely regarded as the first American cookbook. Her ground-breaking publication has become an exceedingly rare museum piece: accounts vary as to how many copies of the first edition remain extant, but the number is well under 10, and perhaps as low as four. And one of those is in the library of the Connecticut Historical Society in Hartford.

The first American cookbook, published in Hartford in 1796.

Photo: Connecticut Historical Society, Hartford

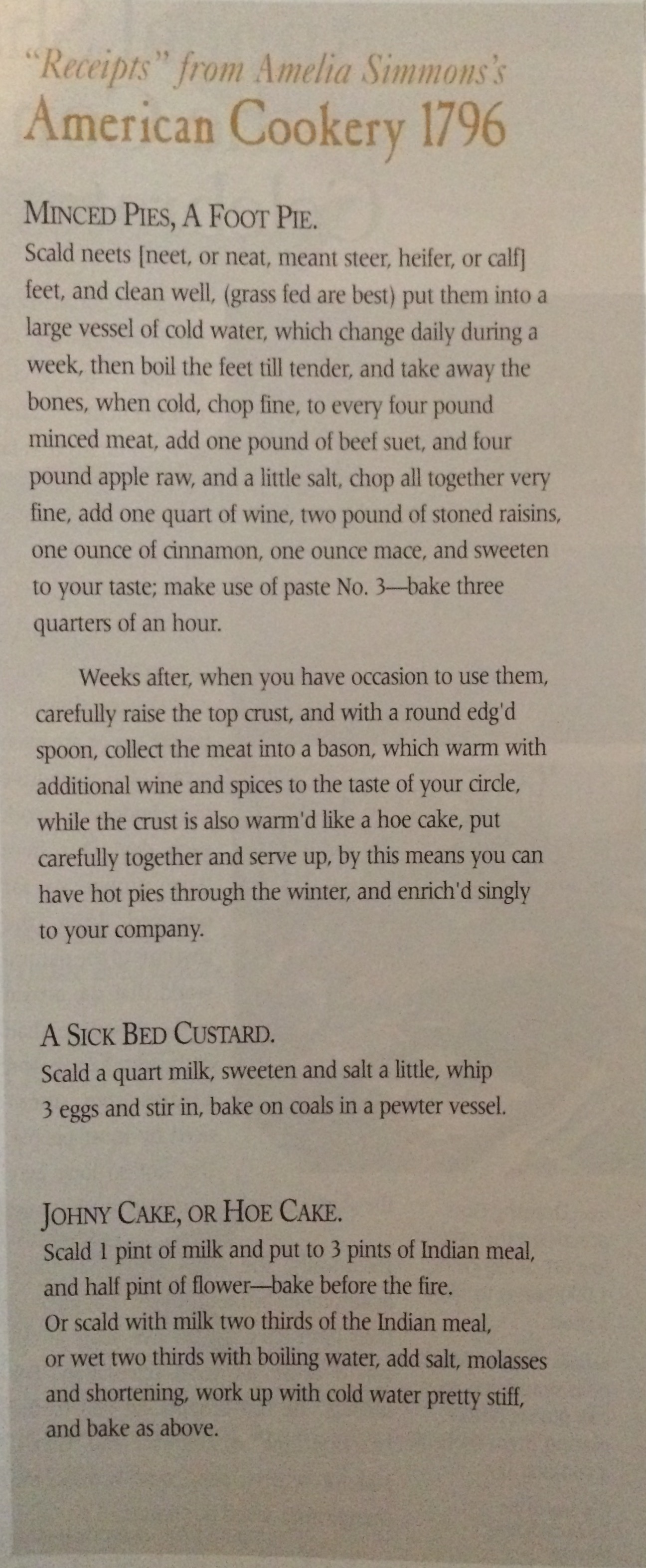

American Cookery, printed in 1796 by Hudson & Goodwin, is the first cookbook to be written by an American and published here; other popular cookbooks of the day were reprints of European cooking guides. According to culinary historian Kathleen Fitzgerald, co-author of America’s Founding Food: The Story of New England Cooking (University of North Carolina Press, 2004), Simmons was the first to incorporate uniquely American ingredients, such as cornmeal, in her “receipts.” She was the first to substitute certain American words for English terms (using “molasses” instead of “treacle,” for instance.) She was the first to use the word “squash” in a cookbook, and her custardy version of “pumpkin pie” was a departure from the English version (which featured pumpkin slices piled between the crusts, apple-pie style) and the progenitor of an American holiday staple. Simmons further altered the course of American cooking by introducing in print the practice of using pearl ash as a chemical leavener (taking over a job previously requiring yeast or egg), an innovation that led to the development of quick breads.

Widely copied and pirated in its day (the contents were routinely plagiarized, despite the fact that the book was among the first to be covered by the U.S.’s 1790 copyright law) and reprinted several times (the first edition, Fitzgerald notes, was republished twice, and the second edition appeared within a year of the original edition), American Cookery remained popular through the early 1800s.

Its author remained somewhat more obscure, though. Fitzgerald says Simmons was probably “a domestic in some family home.” Amelia Simmons identifies herself as “An American Orphan” and directs her advice toward young women similarly situated:

As this treatise is calculated for the improvement of the rising generation of Females in America, the Lady of fashion and fortune will not be displeased, if many hints are suggested for the more general and universal knowledge of those females in this country, who by the loss of their parents, or other unfortunate circumstances, are reduced to the necessity of going into families in the line of domestics, or taking refuge with their friends or relations, and doing those things which are really essential to the perfecting them as good wives, and useful members of society.

The book itself looks more like a pamphlet: its 48 pages are bound with thread, and there’s no “cover” to speak of. It has no illustrations, though the colorful language brings clear images to mind, particularly when Simmons discusses methods for preparing turtle (“about 9 o’clock hang up your Turtle by the hind fins, cut of[f]the head and save the blood..”). Its first dozen pages are devoted to selecting quality ingredients at market (“How to Choose Flesh”). In choosing beef, Simmons advises, ” The large stall fed ox beef is the best, it has a coarse open grain, and oily smoothness; dent it with your finger and it will immediately rise again; if old, it will be rough and spungy, and the dent remain.”

For her part, Simmons, whose book’s full title is American Cookery, or the Art of Dressing Viands, Fish, Poultry and Vegetables, and the Best Modes of Making Pastes, Puffs, Pies, Tarts, Puddings, Custards and Preserves, and All Kinds of Cakes, From the Imperial Plumb to Plain Cake. Adapted to This Country, and All Grades of Life, was not above borrowing material from earlier authors. (What we would consider plagiarism today was common practice 200 years ago, Fitzgerald notes.) But in some instances she distances herself from her European predecessors: ” Garlicks, tho’ used by the French, are better adapted to the uses of medicine than cookery,” she proclaims.

Jennifer LaRue is editor of Connecticut Explored.