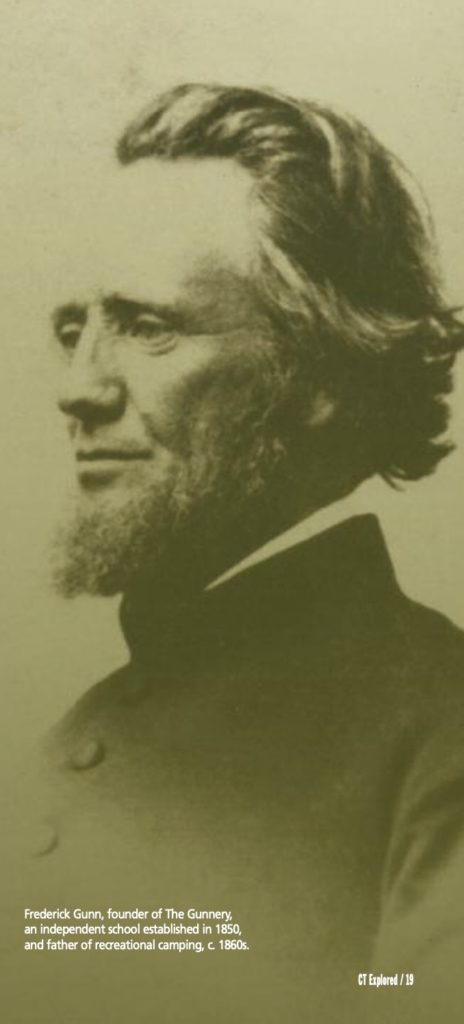

Frederick Gunn, founder of The Gunnery, now known as the Frederick Gunn School, an independent school established in 1850, and father of recreational camping, c. 1860s. Courtesy Frederick Gunn School

By Paula Gibson Krimsky

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue

Frederick Gunn, the iconoclastic founder of The Gunnery, now the Frederick Gunn School, an independent boarding and day school in Washington, Connecticut (founded in 1850), is recognized today as the “father of recreational camping” and a contributor to the phenomenon of summer camp for kids in the United States. He would probably be surprised to hear it.

For him, enjoying and managing in the outdoors was as natural as nature itself. As an educator, he believed that physical activity was inherently a wonderful teacher and an essential component for building character. Having established his school precisely in the middle of 19th century, he continued to develop his educational philosophy—a task that took on new urgency in the face of a gathering crisis: the Civil War.

As the 1850s came to a close, Gunn believed that war between the North and South was the inevitable outcome of the abolition movement, of which he was an ardent supporter. He wanted his students to be ready to fight for freedom and the Union. He led his entire student body on long treks, in effect teaching young people how to survive on bivouac.

Though living in the wilderness was part of the lore of America’s settlement and the westward migration, Washington, Connecticut was far from the wild frontier. The outings Gunn organized were in part geared toward cultivating survival skills and in part toward spiritual inspiration. Americans felt nostalgia for the rural farming culture, which had dominated the country in its early years and now seemed threatened by urbanization in the advance of the industrial age.

Influential writers such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and other Transcendentalists voiced the yearnings of humans for the spiritual healing and stimulation of the outdoors. In his essay “Nature,” published in 1836, Emerson wrote:

The lover of nature is he whose inward and outward senses are still truly adjusted to each other; who has retained the spirit of infancy even into the era of manhood. His intercourse with heaven and earth, becomes part of his daily food. In the presence of nature, a wild delight runs through the man, in spite of real sorrows.

In Walden, published in 1854, Thoreau, who was then living on Emerson’s land around Walden Pond, wrote:

I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.

In his 1861 book Walking, Thoreau wrote:

I wish to speak a word for Nature, for absolute freedom and wildness, as contrasted with a freedom and culture merely civil—to regard man as an inhabitant, or a part and parcel of Nature, rather than a member of society.

Frederick Gunn was an avid reader of both Emerson and Thoreau and frequently referred to them in his correspondence and commended their writings to his fiancée Abigail Brinsmade.

Gunn had been traditionally educated, receiving a degree from Yale University, but he resisted the familiar establishment trappings of the early Victorian period when he created his school. Three pillars upheld his vision: The importance of building character, the need to abolish the institution of slavery in this country, and a reverence for nature. They melded into a core educational philosophy.

Early History

Born on October 4, 1816 in Washington, Frederick William Gunn was the youngest of eight children. His father, a respected farmer and deputy sheriff, and his mother, a devout Christian, both died in his 10th year, leaving his oldest brother John to raise and educate him. Young Fred grew up in Washington and went to school in Cornwall. Nestled in the foothills of the Berkshires, in what was still called Judea by its inhabitants, Washington was a rural, farming community about 12 miles south of Litchfield, then a bustling center on the turnpike between Hartford and Albany. (Washington was the first town in the new country to be named after George Washington, who had passed through there in the campaigns of the Revolution. Judea took the name of Washington when it incorporated in 1779.)

Gunn entered Yale in the class of 1837 and majored in botany. New Haven was then a thriving port city, and the student yearned for the rolling hills and woods of his home town, some 40 miles north. He loved hunting and fishing and is known to have made his own hunting bow in college, “a bow which none but he could fully draw.”

In 1837, he returned to Washington. Eschewing his original plan to become a doctor because of an unavoidable queasiness in the presence of blood and suffering, he began his career as schoolmaster. His former students, in their 1887 biography Master of the Gunnery, described his classes in the period from 1837 to 1846 as very popular and his classrooms “filled to overflowing.”

An Abolitionist Out of Step with his Community

Gunn’s career path was altered by the great national reform movement against slavery. Having been influenced by Theodore Woolsey, his Greek professor at Yale, the writers Emerson and Carlyle, and his brother John’s work in the abolitionist movement, he became an outspoken leader of the antislavery movement in Litchfield County.

The Congregational church was the center of community activity and the social arbiter during this time. In Washington, those roles were personified by Parson Gordon Hayes, an unabashed supporter of slavery. Hayes justified slavery on biblical grounds and delivered sermons condemning the abolitionists. The abolitionist movement in New England of the 1840s was not popular and was regarded as radical. Under the cleric’s influence, Gunn’s teaching became anathema among Litchfield residents, and parents began withdrawing students from his classroom. Senator Orville Platt, quoted in Master of the Gunnery, said that members of the community feared social and political ostracism from the town’s citizens for sending their children to his school.

When it became virtually impossible for Gunn to earn his living as a schoolmaster, his friend Henry Booth from nearby Roxbury invited him to teach at an academy in Towanda, Pennsylvania, a place more tolerant of abolitionist views. Nature remained Gunn’s salvation during this period of exile. He wrote to Abigail, who had remained in Washington, about taking his students to lie on roofs and having them name the constellations in the starlit sky. They took spring walks to identify early flowers and bird songs and walked beside the riverbed in the winter, taking note of animal tracks and hibernation caves.

Public opinion regarding slavery began shifting in New England in anticipation of the Fugitive Slave Law (1850), and in the summer of 1849 a homesick Frederick Gunn, now married and with his first child, accepted the urging of his family and friends to come home to Washington, where they assured him he would be welcome.

A Return to Washington

In 1850 he and Abigail opened their new school in a rambling Victorian home on Washington’s hilltop green, near the Congregational Church that had ostracized him nearly a decade earlier. His teaching methods now proved to be well suited to the temper of the times, and the school grew and prospered. In a speech to educators in 1877 Gunn raised the radical notion that the ideal school would include both boys and girls, and, he added, “is set in the country, or, if in the city, the generous city fathers have afforded it liberal space with trees and flowers.” He was an early proponent of physical exercise and sport as an integral part of the curriculum and participated enthusiastically in student games of baseball, football, and shinny (a forerunner of hockey).

Fishing and hunting were as much a part of the school routines as the reciting of Latin verbs. Gunn was known to declare a holiday from class when the weather was particularly suitable and to lead his students on tramps through the woods and along the waterways, drawing their attention to the wonders of nature hidden under the leaves and behind the hillocks.

The teacher’s appreciation and love of nature and his promotion of outdoor sports led to camping opportunities for the students at the nearby Steep Rock preserve along the Shepaug River and at the four-mile-distant Lake Waramaug. In Master of the Gunnery, Clarence Deming, class of 1866, wrote, “Sometimes in the summer the whole school went for a night’s camp to Steep Rock, a name far too prosaic and tame to fit the unappreciated wonder of nature it describes.”

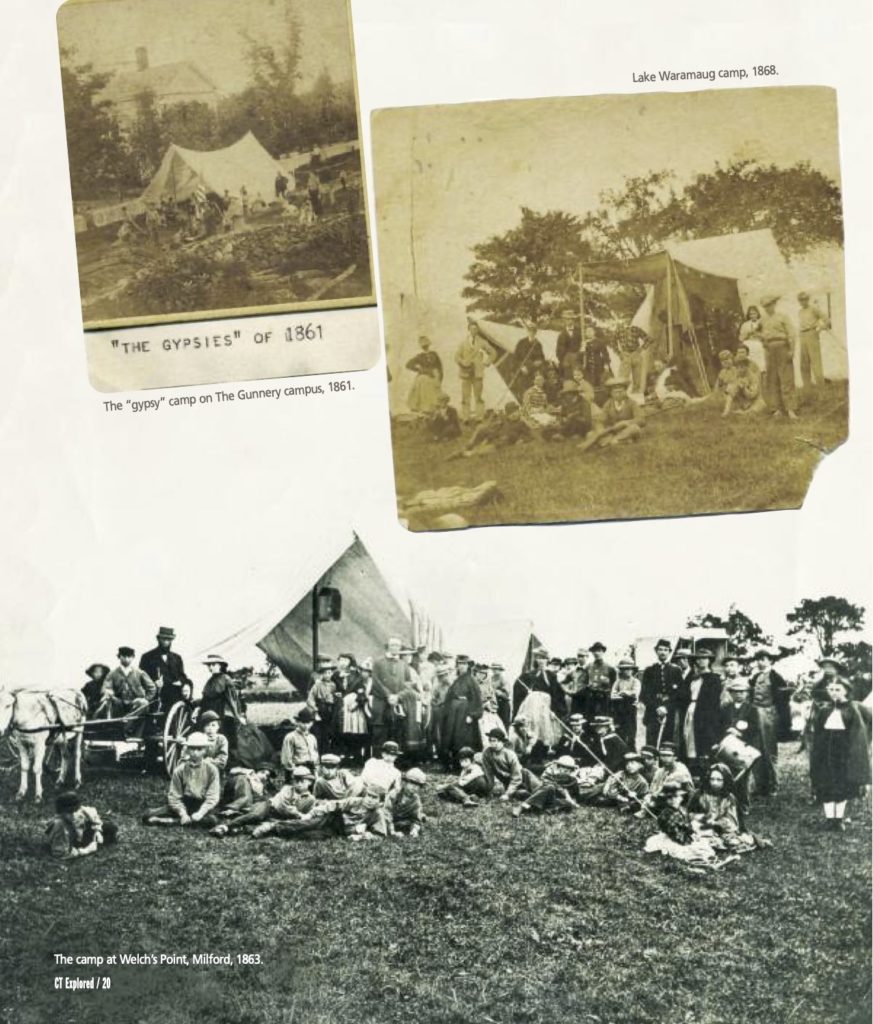

During the early 1860s, Gunn organized long marches for his students, who then numbered about 30 boys and a dozen girls. In 1861 he led his first trek 42 miles from Washington to Welch’s Point at Milford, Connecticut, on Long Island Sound. Every other summer from 1861 to 1865, they camped there for 10 days in August, and, amidst swimming and foraging, they performed military drills in preparation for service in the Union Army.

Gunn didn’t call it “bivouac,” a French word reserved for military activity and originally meaning “to post troops in the night.” The mix of drills and recreation was a hybrid, adapted for education, training, and pure enjoyment. The students called it “gypsying” and named their camp “Camp Comfort.” A Prussian officer, Lt. von Schmeideberg, led the drills. Student Frank Woodruff, class of 1875, wrote a reminiscence about the camps, saying, “Mr. Gunn believed that Gunnery boys should be trained to know themselves men and worthy of their American heritage.” In describing the trips in Master of the Gunnery, Deming wrote:

Old boys came back to join the merry troop, which, reënforced by local friends of the school, many of them young ladies made up a party of 60 or more … It was a jocund ten days that followed with its sport in the surf, its evening songs, its dances by the turf by night, its ball games and its touches of more tender sentiment in the moonlight … No one who camped by the sea with us then can ever forget the thrill as there rang upon the air of night from the throat of a sweet singer as she stood in the firelight, those inspiring words of the “Battle Hymn of the Republic.”

The success of the Civil War-era camps gave way to such school-sponsored summer camps as Point Beautiful and Camp Hawke in the 1870s at Lake Waramaug. A letter in The Gunnery’s archive, whose author and date are lost to history, spoke of the preparations, the tasks, the games, and the morning bugle call for the “Family Meeting,” wherein Gunn would give advice and “cautions” about the coming day: “no swimming alone, the big boys to care for the younger ones, etc.” In the evening, they would sing “camp songs,” with hand organ accompaniment played by Gunn. The letter continues,

Then with a few more words of caution and kindly advice from the head of the “family,” we would seek our different amusements. Some would go hunting, others would try fishing, still others a row—to see some new or attractive part of the lake, and perhaps a few would try letter writing… . No less interesting were the games of base-ball in which the ‘flower’ of the ball players would join and play against the nines which flourished thereabouts. [On Sunday] there would assemble campers, friends from Washington, and many people from the farms about, and from the several hotels on the shores of the lake, to hear a sermon telling perhaps of nature and Him who created it …after two weeks of varied interest we returned to enjoy what? I cannot tell what did not seem a treat. Even eating off china seemed to lend a pleasure to our new existence.

An August 1879 article in the Litchfield Enquirer mentions 20 tents and 50 campers, including prominent “old boys” such as William Hamilton Gibson and H.W.B. Howard (nephew of Henry Ward Beecher) and friends of the school, including author Josiah Holland (a Gunnery parent), and Col. Horatio C. King, a much decorated Civil War veteran and composer of some repute.

The camp sessions drew to a close when the educational calendar formalized in the 1880s and 1890s as compulsory education took hold. The rural custom of a spring respite for planting and a fall respite for harvest gave way to a long summer break and students went home during July and August.

Frederick Gunn died in 1881. His camping legacy was continued by his son-in-law John Brinsmade, who inherited the school, and has been supported by all nine of the subsequent headmasters. An annual commemoration takes the form of a school walk of about eight miles, which today takes place as close to Gunn’s birthday in October as possible.

The tradition continues. The Gunnery head of school Peter Becker hikes with students, 2012. photo: Phil Dutton, The Frederick Gunn School

The more permanent summer camp that became a fixture for children at the turn of the century was a natural outgrowth from the recreational bivouac of Gunn’s time, although credit cannot be assigned to Gunn alone. The next recorded camp was for young adult women of the YWCA at Sea Rest in Asbury Park, New Jersey, which was established in 1874. It was called a “vacation project.” Summer F. Dudley established a YMCA camp in Newburgh, New York in 1885. A.S. Gregg Clarke, a member of the Gunnery class of 1889 whose family’s reversal of fortune prohibited him from attending law school, founded the Keewaydin canoeing camp in Maine in 1893. He called the camp, which is still in operation, “a resurrection” of the old Gunnery camps, and many Gunnery students attended. He ran the camp in the summer and taught at The Gunnery during the school year. His camp quickly became very popular. The American Camp Association cites on its Web site a 1922 statement by Charles W. Eliot, former president of Harvard University, that “the organized summer camp is the most important step in education that America has given the world.”

Many of Gunn’s students shaped their lives around his lessons and love of the outdoors. William Hamilton Gibson, class of 1866, became a prominent naturalist, author (whose first book was called Camp Life and the Tricks of Trapping), and illustrator, known for his meticulous depiction of such natural phenomena as the bombardier beetle and the cross fertilization of plants by bees. Ehrick Rossiter, class of 1870, was a renowned architect known for his grand summer “cottages” around Washington and for setting his buildings into the landscape. Richard Burton (no relation to the 19th-century British explorer), class of 1876, became a well-known lecturer who spoke about the natural wonders of the world.

The camping movement in the United States is officially recognized as having begun in 1861, with the founding of Gunn’s camps in Milford, Connecticut. In 1986, the 125th anniversary of that founding, the American Camping Association celebrated the anniversary by replicating the walk to Milford and holding a camp on that town’s Gulf Beach for 1,500 campers from around the world. The Gunnery today continues to send its students on camping and hiking expeditions through the activities of its Outdoor Club and the “Sophomore Saunter,” in addition to the annual school walk.

Frederick Gunn was a compelling individual who developed a decidedly different view of education in the Victorian era, but he was not an egotist. The school was simply inseparable from the man; to some extent, it still is. Gunn left a lasting legacy to the institution, its students, the town of Washington, and ultimately to the country that he loved.

Paula Gibson Krimsky is the archivist and school historian at The Gunnery. She is the great-granddaughter of William Hamilton Gibson, who camped with Frederick Gunn in the 1860s, and the granddaughter of his son Hamilton, The Gunnery’s third headmaster.

Explore!

“Educated in One Room,” Summer 2007

“Jim and Jane Henson Create the Muppets and More,” Fall 2017

“Connecticut’s Historic Trails,” Summer 2008

Read all of our stories about Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS page

Read all of our stories about the Landscape & Environment on our TOPICS page