SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE

By Karen Falk and Karen Frederick

(c) Connecticut Explored, Inc. Fall 2017

A Connecticut farmhouse with an artistic pedigree, a large leafy yard, and plenty of room for invention and play—this was the Greenwich home where Jim and Jane Henson, creators of The Muppets, chose to raise their family from 1964 to 1971. In this place, they found fertile ground to cultivate their creative expression, develop distinctive television work, and, drawing from their parenting experience, help launch educational revolutions both locally and nationwide. Their story is told in Jim and Jane Henson: Creative Work, Creative Play, a special exhibition on view at the Greenwich Historical Society through October 8, 2017.

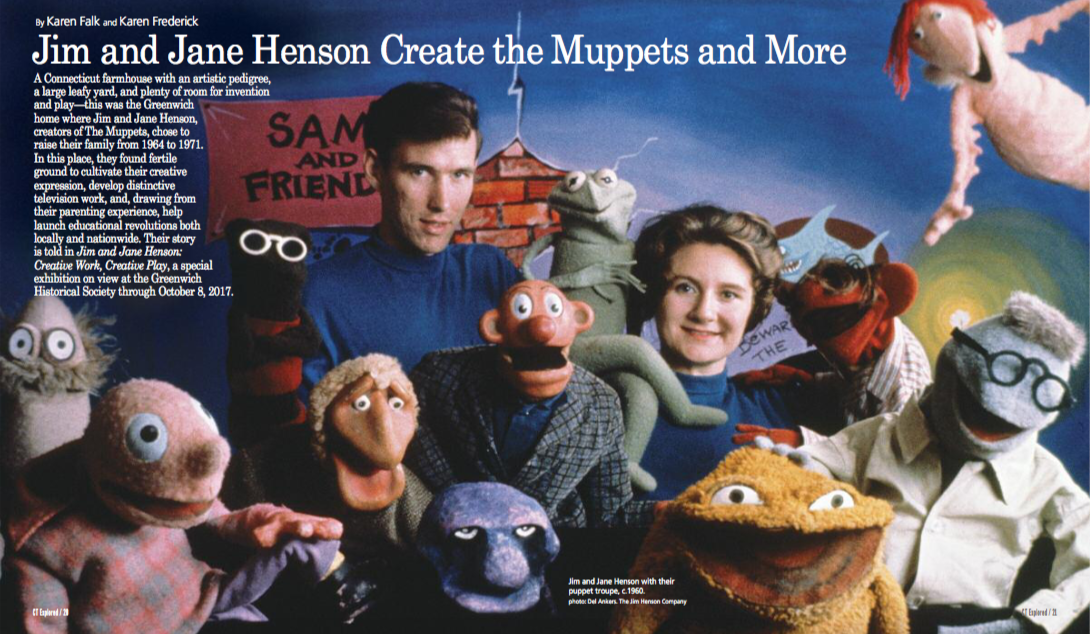

The foundation for what would be an exceptionally formative period was laid during the decade preceding the Hensons’ purchase of the house on Round Hill Road in Greenwich in 1964. Jim Henson (1936 – 1990) and Jane Nebel (1934 – 2013) met as art students at the University of Maryland in 1954. Having made his first puppets and television debut that summer, Jim recruited Jane to be his production and performing partner. By the spring, they were featuring a cast of characters, already called Muppets, in their own five-minute show, Sam and Friends, on the local Washington, D.C. airwaves, and had introduced a frog-like personality named Kermit. Jim and Jane were natural collaborators, sharing a subversive sense of humor and encouraging each other’s artistic instincts. In 1959 their partnership turned romantic, and, newly married, they initiated the seamless interplay of work and family that would be a constant throughout their lives and prove essential to their innovations and success.

top left: photo: Juliet Newman; Oscar the Grouch (c) 2017 Sesame Workshop, all rights reserved; right: The Jim Henson Company

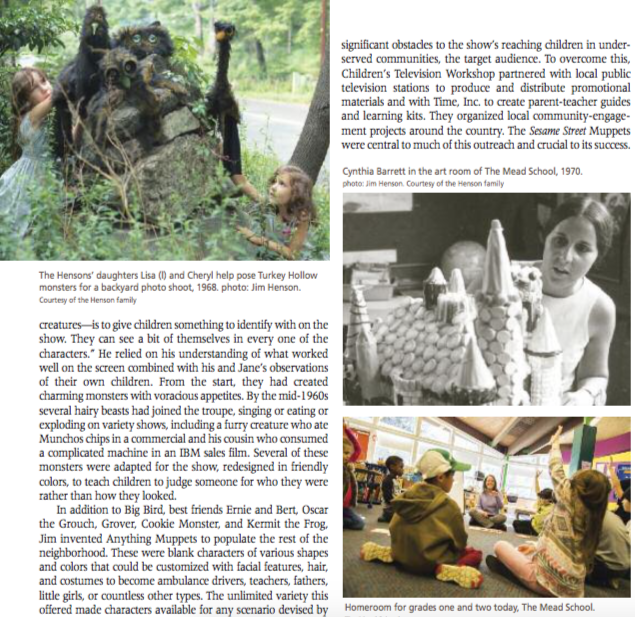

The popularity of The Muppets spread quickly, leading to performances on nationally broadcast programs and work on numerous advertising campaigns around the country. Almost weekly appearances on NBC’s Today Show prompted Jim and Jane, and their two daughters Lisa and Cheryl, to move from Washington, D.C. to New York in 1963. After a year in Manhattan and the birth of their third child, they decided to move to the suburbs. Charmed by the rural and historic feel of nearby Greenwich, they found a 19th-century farmhouse on Round Hill Road surrounded by woods—the same woods, brook, and Horseneck Falls that had provided inspiration for the impressionist painter John Henry Twachtman, who lived in the house from 1890 to 1899.

The Hensons’ new home inspired a creative project right away. In that first year Jim built a dollhouse for his daughter Cheryl modeled on the house, complete with dormers in the roof and chimney stonework cleverly made with cut and painted sandpaper. Cheryl’s dolls moved in, and over the years she and her father added roof shingles, custom-turned balusters, electric lights, and handmade furniture. A keen observer, Jim watched his children’s play and delighted in the antics of the family cats as they joined the fun. Six years later, for one of several short films for Sesame Street inspired by his family life, Jim filmed two girls and two dolls interrupted by two cats while playing with Cheryl’s dollhouse.

The ability to step outdoors into nature and be inspired to create was important to both Jim and Jane. On vacations from work they often sketched side-by-side, recording the waves energetically lapping the base of a lighthouse or the expansive quiet of a desert scene. Jim painted large canvases of light filtering through the trees, and Jane roamed the woods collecting stones with interesting shapes to incorporate into her ceramic sculptures. In a 1982 essay, Jim wrote, “I find that it’s very important for me to stop every now and then and get recharged and re-inspired. The beauty of nature has been one of the great inspirations in my life. Growing up as an artist, I’ve always been in awe of the incredible beauty of every last bit of design in nature. The wonderful color schemes of nature that always work harmoniously are particularly dazzling to me. One of my happiest moments of inspiration came to me many years ago as I lay on the grass, looking up into the leaves and branches of a big old tree in California. I remember feeling very much a part of everything and everyone.”

Along with their television work during this period, Jim pursued a parallel career as a filmmaker. He produced an array of short experimental films, both animated and live-action, including his Academy Award-nominated Time Piece (with scenes shot along Greenwich Avenue). As Twachtman had been inspired to capture the colored light in the woods more than a half century earlier with oil paints, Jim used moving images in producing the 1965 short film Run Run with his performing partner Frank Oz. Celebrating the natural playground around them, they filmed the Hensons’ young daughters, Lisa and Cheryl, joyfully running through the changing colors of the woods, shadowed and lit by the sunlight, ultimately meeting their mother Jane, who, in a red dress reflective of the autumn leaves, leads them home. Though the film was never screened commercially, Jim gained important experience in meshing filmed images with music tracks to evoke an emotional response; he would draw on this skill when making films for Sesame Street and for his fantasy feature films in the 1980s.

Indoors, family life included every kind of project imaginable. Jane remembered that, “At home, we had all kinds of things going on all the time. All kinds of creative things going on, so if there were puppets, they were made out of wooden spoons in the kitchen and Dixie cups and things like that. People were dressing up and making things all the time. A general feeling of creativity was always around the house.” Jim and Jane watched their children at play, deeply interested in the embedded learning processes. In 1967 Jim demonstrated this in a one-minute film for a competition at Expo ’67 in Montreal that he initially called Learning (but ultimately named Wheels That Go), featuring his three-year-old son Brian as he observed wheeled vehicles and then imitated what he saw with toy cars. By this time the Hensons had four small children at home, and along with noting their experience during play, Jim and Jane were keenly aware of the influence of television on this mini focus group. They saw that with an educational emphasis, television could have a tremendous impact. They were uniquely suited to play a major role in harnessing the power of television as a tool for teaching.

In July 1968 Jim and Jane, along with other artists, educators, and media professionals, were invited by the newly created Children’s Television Workshop (now Sesame Workshop) to attend a series of curriculum seminars to consider the question “Can television be used to teach young children?” CTW co-founders Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrisett sought collaborators who could bring diverse viewpoints and experience to the development process and help to exploit the methods utilized by entertainment programming and advertising to reach audiences. The Hensons’ decade working in both fields made them obvious potential contributors to what would be an hour-long television program for preschool-aged children that both entertained and educated: Sesame Street. When the program’s co-creator Jon Stone, a writer and director who had worked with Jim on several projects during the 1960s, was asked to recommend puppets to mingle with the interracial human cast to create a vibrant, diverse, child-friendly community for the show, he suggested that The Muppets were the best possible choice.

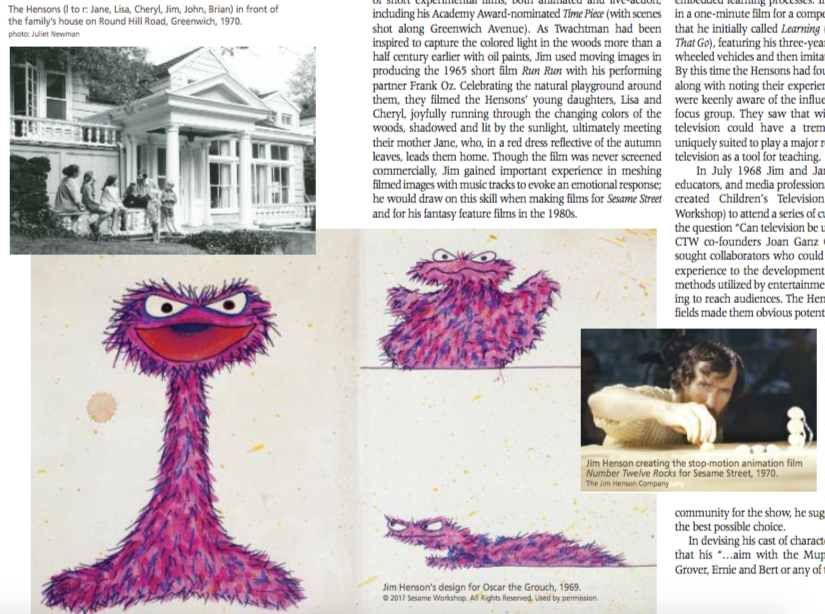

In devising his cast of characters for Sesame Street, Jim noted that his “…aim with the Muppets—whether it’s Big Bird, Grover, Ernie and Bert or any of the other assorted big and little creatures—is to give children something to identify with on the show. They can see a bit of themselves in every one of the characters.” He relied on his understanding of what worked well on the screen combined with his and Jane’s observations of their own children. From the start, they had created charming monsters with voracious appetites. By the mid-1960s several hairy beasts had joined the troupe, singing or eating or exploding on variety shows, including a hairy beast who ate Munchos chips in a commercial and his cousin who consumed a complicated machine in an IBM sales film. Several of these monsters were adapted for the show, redesigned in friendly colors, to teach children to judge someone for who they were rather than how they looked.

In addition to Big Bird, best friends Ernie and Bert, Oscar the Grouch, Grover, Cookie Monster, and Kermit the Frog, Jim invented Anything Muppets to populate the rest of the neighborhood. These were blank characters of various shapes and colors that could be customized with facial features, hair, and costumes to become ambulance drivers, teachers, fathers, little girls, or countless other types. The unlimited variety this offered made characters available for any scenario devised by the writers to teach any lesson thought worthy by the researchers behind the scenes.

The Muppet residents of Sesame Street lived among the most diverse human cast of any show gracing the airwaves in the 1960s. This was deliberate—an important method of teaching tolerance and understanding while also reflecting the varied audiences the show’s producers hoped to reach. Within a year of the November 1969 premiere, research demonstrated that children were learning from Sesame Street. There were, however, significant obstacles to the show’s reaching children in under-served communities, the target audience. To overcome this, Children’s Television Workshop partnered with local public television stations to produce and distribute promotional materials and with Time, Inc. to create parent-teacher guides and learning kits. They organized local community-engagement projects around the country. The Sesame Street Muppets were central to much of this outreach and crucial to its success.

Along with creating and performing Muppets for the program, Jim produced other material to help fill the need for 130 hours of material for each season. Relying on the tools he developed from his experimental film work, home movies, and advertising work, Jim made about two dozen short films for Sesame Street. The very first, made in early 1969 and airing as part of the third episode, was Body Parts vs. Heavy Machinery. Featuring his son Brian and a friend mimicking construction vehicles in a sandbox with spoons and ice cream, the film represents Jim’s expanded thinking about visual representations of the learning process, similar to his Wheels that Go film from two years earlier.

Most of Jim’s short Sesame Street films drew from his experience in advertising and featured snappy commercial-like lessons about counting or other concepts. He produced two series of shorts, many featuring his children. The first series, created in 1969, consisted of 10 one-minute live-action films. At the end of each film a baker carrying the appropriate number of cakes fell down the stairs. The second series, created in 1970 and 1971, consisted of 11 films (Numbers Two to Twelve) using several types of animation. These included stop-motion, cut-paper, paint, Scanimate (an early digital process), and traditional cel animation, demonstrating the breadth of Jim’s talent and his fascination with a wide variety of media. His film of Cheryl’s dollhouse was part of this series.

The Hensons’ family life and their efforts as artists and performers, combined with their interest in how children learn, provided the foundation for their essential contributions to the extraordinary cultural, educational, and media impact of Sesame Street on global audiences. Closer to home, they worked in a similar vein to enhance and support their Greenwich community, performing at school fairs and helping to found a groundbreaking institution, The Mead School for Human Development, Inc.

Lisa and Cheryl Henson were students at the local North Street School, where they met their favorite teacher, Cynthia Barrett, in the art room. At that point Barrett had been at North Street for nine years, and Dr. Elaine de Beauport approached her to join the staff at a new school, The Mead School for Human Development, Inc. De Beauport believed that each student learned differently and that humanities were as important as the standard academics of reading, writing, and math. Instead of classrooms, the school would have curriculum centers where children were free to work in their areas of interest, thereby providing a place for each child to gain self-confidence and self-esteem. The role of the teacher was more than that of instructor, incorporating the role of friend and facilitator. Barrett was intrigued both by the idea of seeing children for more than one hour a week and making art a core part of the curriculum. She was the first Mead School teacher hired and would teach there for the next 17 years.

The school was opened in 1969, the year that Sesame Street premiered, in the classroom wing of the Second Congregational Church on Putnam Avenue in Greenwich. Jim and Jane, impressed with Barrett’s approach to teaching, followed her to Mead, enrolling all four of their children there. Like Elaine de Beauport, Jim and Jane believed that art should be central to education and were enthusiastic participants in the school’s founding. Not only did the Henson children attend, but Jane Henson also became Cynthia Barrett’s first art center assistant. Cynthia found Jane’s creative mind and gentle, encouraging approach to be huge assets. In 1974, needing more space, the school moved to Byram, a section of Greenwich. What had once been two factories—one a nut-and-bolt factory and the other a button factory—was transformed into a space of light and art by Elaine de Beauport, along with architects and colleagues, whose work was funded in part by the Hensons. In 1986, again needing more space, it moved to Riverside, another section of Greenwich, before moving in 1997 to its current home in Stamford, where it continues to educate children through the eighth grade. The Henson family moved to Bedford, New York in 1971 for a larger house on a less busy road but continued to drive their fifth child, Heather, to The Mead School for four years so that she too could benefit from its arts-filled education.

The creators of Sesame Street and the founders of The Mead School took an uncharted approach to the education of children. As contributors to both experiments, the Hensons, relying on their experience with their own children, instinctively believed that learning can and should be fun. Jim and Jane Henson broke new ground during a seminal period of educational television. Their celebration of imagination and creativity continues to inspire and educate new generations around the world.

Karen Falk is archives director for The Jim Henson Company. Karen Frederick is curator for the Greenwich Historical Society. Additional research was conducted by Susie Tofte.