by Clarissa J. Ceglio, Janice Matthews, & Elizabeth Normen

by Clarissa J. Ceglio, Janice Matthews, & Elizabeth Normen

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. SUMMER 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

If a town is lucky enough to still have a one-room schoolhouse, the community invariably has a soft spot for it. In celebration of these symbols of hometown pride, we’ve selected a handful from around the state that are still interpreted as schoolhouses.

If a town is lucky enough to still have a one-room schoolhouse, the community invariably has a soft spot for it. In celebration of these symbols of hometown pride, we’ve selected a handful from around the state that are still interpreted as schoolhouses.

Though they were the norm for educating town children for more than 100 years, one-room schoolhouses, especially those that remain intact and on their original site, are now fairly rare. In 1899, there were 1,110 active single-teacher schools, according to state historian emeritus Christopher Collier’s research for his book-in-progress, “The Connecticut Public Schools: A History.” The first such schools opened as early as the 1740s (the secretary of the state board of education noted in 1921 that some were “quite as old as the nation”), and the last one did not close until 1967.

Because children usually walked to school, most towns had several one-room schoolhouses, each serving its own portion of the town. Some towns had more than a dozen. The shift to larger schools serving more children began in the late 19 th century and gained momentum after the Consolidation Act of 1909, which required towns to establish a board of education and consolidate schools for better quality delivery of education. By 1949, Collier notes, only 55 one-room schoolhouses remained in operation, most accommodating fewer grades than the customary 1 through 8. Once they closed, they often reverted to the owner of the property on which they stood; today, while a town might have one or two fairly intact schoolhouses, many more still dot the landscape, long ago adapted for private use.

The quality of the education provided in one-room schoolhouses, especially early on, varied tremendously. An 1837 report to the Connecticut legislature summarized the shocking results of a statewide survey:

1) parents exhibited very little interest in the public schools; 2) teachers were poorly qualified and received only an average of $14.50 monthly for men and $5.75 monthly for women (exclusive of board); 3) many school committees and visitors failed to perform their duties; 4) a hodgepodge of books was used; 5) many schoolhouses were poorly constructed and equipped; [and]6) many school-age children were not in school….

As a result, the legislature established a board of commissioners to oversee the local school boards (then called societies) and appointed Henry Barnard (1811-1900) as its first secretary. He is credited with reforming Connecticut’s public schools and gained a national reputation in the field of public school education.

A one-room schoolhouse that no longer exists but that is worth noting is the Colchester Colored School (c. 1803-1840). The fragments of its story that survive are a reminder of the largely unrecorded struggles of African Americans, beginning in colonial times, for access to a quality education in Connecticut’s towns and cities. When Bacon Academy was built on the site of the town’s First District School in 1803, the schoolhouse was moved behind the Colchester Federated Church on South Main Street and reopened as a publicly funded segregated school for black children—though black and white children had formerly attended Colchester’s one-room schoolhouses together, according to research conducted by Gail Joslin. As African Americans sought access to a decent education, the Colchester Colored School reportedly attracted students from across Connecticut and other states, at one point reaching a peak enrollment of between 30 and 40 students. Though it did not close until 1840, it was likely affected by the 1833 law preventing schools from educating out-of-state African Americans without a town’s permission. The law was passed in response to Prudence Crandall’s school and, although it was repealed in 1838, opposition to improving education for African Americans remained widespread.

If there’s a one-room schoolhouse in your town, chances are there are folks still around who remember attending since several remained in use well into the mid-1900s. Its restoration has likely been undertaken by volunteers with donated materials or money collected by local schoolchildren; the restoration may even have been an Eagle Scout project. Many are still educating school children, at least part time. One thing is certain: it’s a point of local pride.

Photos courtesy of the respective historical societies. HRJ thanks the participating historical societies for their assistance with this piece.

Still Educating

The Quasset School, Woodstock

Each spring for the past 30 years, a short walk has taken third graders at Woodstock Elementary School back 100 years—to the Quasset School next door. There they learn about local history by being immersed in the experience of being educated in a one-room schoolhouse. According to teacher Irene Wheeler, girls dress in mob caps, skirts, and aprons, the boys in vests and kerchiefs, and they learn their lessons on slates, by rote memorization, and by making copy books with quill pens. If the weather is chilly, the old woodstove is fired up as the only source of heat. Parent volunteers offer lessons in carding wool, weaving, or making butter. Though not all the furnishings are authentic to the Quasset School, most come from one of the 17 one-room schoolhouses the town once had. The school is also taller than it was originally. When it was moved from an old apple orchard on West Quasset Road, it was taken apart brick by brick. The bricks were numbered and put back in their original order, but every few rows an additional course of bricks was added for strength.

Opened c. 1738-1748, possibly replacing an earlier school; closed 1943. Moved in 1953 to present site adjacent to the Woodstock Elementary School.

Open Sundays 1-4, July and August. Free admission. Information: (860) 928-1035; www.woodstockhistoricalsociety.org

A Time Capsule

Pine Grove School, Avon

By Nora Howard, historian of the Town of Avon

Pine Grove Schoolhouse No. 7 is a Gothic Revival design by Rhode Island architect Thomas Tefft, whose work was praised by Connecticut school supervisor Henry Barnard as “among the best specimens of school architecture.” The Avon Historical Society restored the site during the Bicentennial using surviving photographs of the school’s interior. A mix of original and donated artifacts illustrates how the one-room schoolhouse evolved over its 84 years as community needs and technologies changed. Original features include an iron sink, umbrella stands, coat hooks, chalkboards, and an enclosed bookcase behind the teacher’s desk. Visitors may sit at the desks—original to this or other Avon schoolhouses—and imagine how it felt to be a student in days gone by.

Opened 1865; closed 1949. On its original site.

Open Sundays 2-4, June-September and by appointment October-May. Donation suggested. Information: Avon Historical Society president Ed Borkoski, (860) 677-7086.

New Life at New Location

The Cooley School, Granby

By Carol Laun, archivist/genealogist, Salmon Brook Historical Society

Children who attended Cooley School on East Street enjoyed the dubious distinction of trudging several yards across the state line to visit the outhouse, which was located in Massachusetts. After its closing, the school, which like many of its day was located on private property, was boarded up until the farm’s owner Merrill Clark, whose mother had been a Cooley teacher, donated the building to the Salmon Brook Historical Society in 1972. In 1980, the Society moved the school and outhouse nearly 5 miles to its complex on Salmon Brook Street. Volunteers restored the school and furnished it with desks, books, and maps rescued by residents when Granby’s one-room schoolhouses were closed. Original fixtures include a chinning bar in the boy’s doorway (installed in the 1920s to meet the state’s physical education requirements) and a blackboard displaying arithmetic problems from the last class in 1948. Fate provided the final touch of authenticity when a snowplow broke the state-line marker at the original site. The Society acquired the granite marker and installed it as a reminder that the outhouse originally stood in Massachusetts. Today, Granby second graders again sit at desks with inkwells and slates to learn about schooling 130 years ago—and to wonder who carved the initials in the desks.

Opened c. 1878; closed 1948. Moved in 1980 to the grounds of the Salmon Brook Historical Society.

Open Sunday 2-4, June-September. Admission: $2; $1 for those under 12 or over 65. Information: (860) 653-9713; www.salmonbrookhistorical.org.

More Than 200 Years of Service

The Little Red Schoolhouse, Gaylordsville

For 227 years, Gaylordsville’s Little Red Schoolhouse operated as a public school and was the last active one-room schoolhouse in the state when it closed in 1967. It’s also one of the oldest still standing. It was built in 1740, moved a short distance and repaired in 1858, and enlarged and renovated again in 1872. Electricity was installed and an oil heater replaced the coal stove in 1935, but running water wasn’t added until 1952. Over the years, as the town grew, fewer and fewer grades were taught at the Little Red Schoolhouse until, in its final years, only children in grades 1 and 2 were educated there. Upon its closing, a group of residents formed to assure its preservation, and today it serves as the Museum of Gaylordsville and the home of the Gaylordsville Historical Society.

Opened 1740; closed 1967. On its original site. Open Sunday 2-5, July and August. Free admission; donations accepted. Information: (860) 350-0300; www.gaylordsville.org.

Undergoing Restoration

The Green School, Canterbury

In the mid-1800s Canterbury boasted 14 one-room schoolhouses. Gradual consolidation of the districts during the 20 th century culminated with the opening of the Dr. Helen Baldwin School in 1947. For a short period afterward, the Green School hosted kindergarten classes and then served as the town’s library building until 2001. Soon after, the Canterbury Historical Society began restoring the structure to its early 20 th-century appearance. Individuals who attended Canterbury’s district schools in the 1930s and ‘40s have aided the all-volunteer effort by providing memories, photos, and memorabilia. The Yankee tendency to save things has also proven valuable: the original globe ceiling lights were found in the attic, and the school’s chalkboards were revealed when the library shelves were pulled from the walls. Photos of the restoration work can be seen on the society’s Web site.

Opened c. 1850; closed c. 1947. On its original site.

Open by appointment during the renovation; future open house events, including “District School Reunion Day” in September 2007, are planned. Information: www.canterburyhistorical.org.

Famous Schoolteacher

Nathan Hale Schoolhouses, East Haddam and New London

In October 1773, 18-year-old Nathan Hale, newly graduated from Yale College, assumed his first teaching post in East Haddam, where he oversaw 33 students ages 6 to 18. The town must have seemed isolated in comparison to urbane New Haven, for Hale wrote it seemed “inaccessible, either by friends, acquaintance or letters.” Within 5 months he secured a new position at Union School in bustling New London. He found the schoolhouse “very convenient,” further noting that his male pupils consisted of “about 30 Scholars; ten of whom, are Latiners and all but six of the rest are writers.” In the summer, he also instructed a class of girls. Hale’s tenure in New London proved brief. In July 1775, having accepted a commission as 1 st Lieutenant in the 7 th Connecticut Regiment, Hale tendered his resignation, noting, “Schoolkeeping is a business of which I was always fond; …but at present there seems an opportunity for more extensive public service.” Prophetic words from a man who just 14 months later would die a national hero. Today, the Connecticut Society of the Sons of the American Revolution (CTSSAR) operates both schools as museums. Aided by a planning grant from the Connecticut Humanities Council, CTSSAR is currently raising funds to implement permanent exhibits at both sites, add an interpretive center at East Haddam, and continue restoration work in New London. [Source for Hale’s letters: George Dudley Seymour, Documentary Life of Nathan Hale ( New Haven: private press), 1941.]

East Haddam School

lOpened 1750; closed 1799. Moved in 1800 (a bust of Hale at Goodspeed Plaza marks the original school site) and again in 1900. Open Saturday and Sunday noon-4, Memorial Day-Labor Day. Admission: $2 for adults, free for children.

New London ( Union) School

Opened 1773; closed 1834. Moved five times between 1834 and 1988. Open Wednesday-Sunday 11-4, May 1-October 31. Admission: $2 for adults, free for children. Information for both sites: (860) 873-3399 or www.ConnecticutSAR.org.

A Day in the Life…

The Carter Street School and the Rock School, New Canaan

While teaching at a one-room schoolhouse in New Canaan, Margaret Mary Corrigan (1880-1959) recorded her experience as a teacher in a diary (available at the New Canaan Historical Society). Following are excerpts (with her punctuation retained).

Thursday December 1-1898

We have had a heavy snow storm-quite a blizzard I think! This morning I waded through snow 6 feet deep on my way to school. A pathway had been dug part of the way thru the rest I had to struggle the best I could. … The fire was out. No pupil had arrived, so there was nothing to do but start a fresh fire. Our heater has a good draught so it was not long before the school room was warm and comfortable.

At last I received a lesson paper from the Nat. Correspondence Institute. I took the course in algebra. In this first course there are 10 different problems. I can work only 7.

Wednesday-January 3-1899

…The past 6 years have brought a great change in my life. 6 years ago I was a pupil in this very school. The teacher then a Miss Raymond was such a tyrant that she suppressed any natural talent that I had and in her presence I felt and acted stupid. …

One day she gave me a problem in mental arithmetic. It consisted of adding, subtracting, multiplying & dividing in fractions. When I gave her a hopeless look, showing that I did not know the answer she told me that I should be ashamed of my stupidity!

How little did she or I then think that when she was in her grave a year or two I should be presiding at her desk and enjoying my authority.

The Carter Street School

Opened 1868; closed 1957. On its original site.

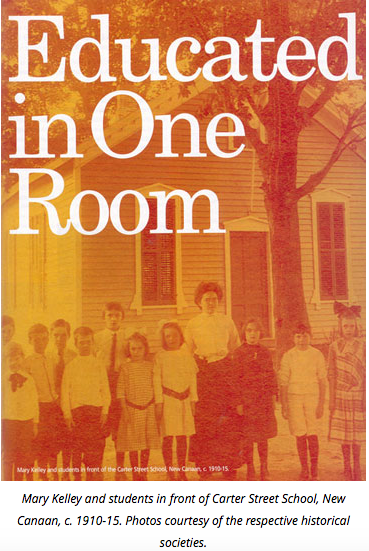

Owned by the New Canaan Historical Society. Open only on special occasions, including an open house and annual ice cream social on Sunday, June 10, 1-4 p.m. Visitors see the schoolhouse as it was left when the last school teacher, Mary Kelley (a former student who began teaching there in 1910) closed the doors in 1957. Unique feature: charming original paintings illustrating Aesop’s Fables by Justin Gruelle (1889-1978), brother of Raggedy Ann creator Johnny Gruelle.

The Rock School

Opened 1799; closed 1930. Moved in1973 to the Historical Society’s campus.

Call for open hours: (203) 966-1776; www.nchistory.org.