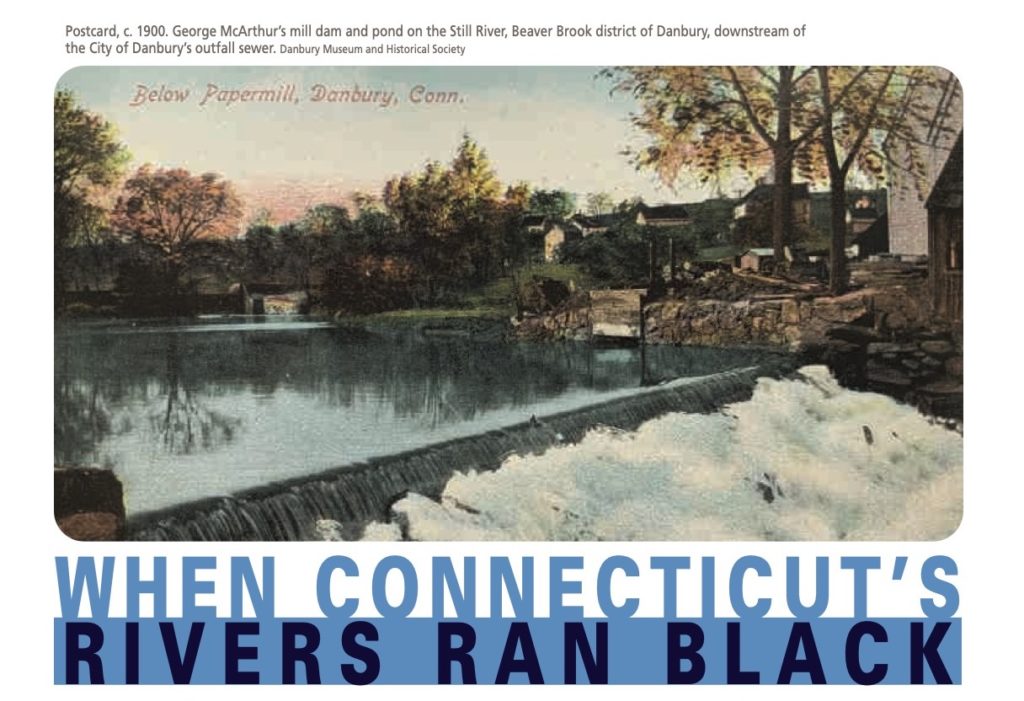

Postcard, c. 1900. George McArthur’s mill dam and pond on the Still River, Beaver Brook district of Danbury, downstream of the City of Danbury’s outfall sewer. Danbury Museum and Historical Society

By William Devlin

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc Spring 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

George McArthur could tell the day of the week by the shade of black presented by the water of Danbury’s Still River flowing over his milldam in 1893. McArthur made wrapping paper there, but at the time, Danbury produced most of the country’s derby hats, and at the end of every week, its factories emptied their dye vats into the sluggish stream. Earlier each week, the river’s color was tainted by raw sewage pouring from the City of Danbury’s outfall sewer, a mile and a half upstream. The smell from the untreated effluent made his workmen sick. Cows developed rashes after wading in the river, and families fell sick after eating fish caught in it. “What next from the stream,” asked The Danbury News, “is the question of the day.”

Danbury papermill owner George McArthur joined lawsuits challenging both industrial and sewage pollution. From Commemorative Biographic Record of Fairfield County, Connecticut, vol. II (Chicago, J.H. Beers, 1899). Danbury Museum and Historical Society

McArthur had complained to the city’s hat manufacturers association about the dye pollution seven years earlier, and as a result the association had paid him $1,800 and identified a new source of water, a member of the group would later testify in court in February 1895. But, disgusted by the raw sewage, McArthur was now ready to join another lawsuit—one that was instigated by his neighbor and fellow mill owner George Morgan, whose millpond was filling up with raw sewage and who was asking the state courts for compensation and for an injunction against the city to stop dumping its waste into the Still River.

In the 1890s riverside property owners and farmers across the state turned to the courts to force city governments to stop polluting streams. Their fights are recorded in detail in court documents, in the annual reports of the state board of health, in the reports of the state supreme court, which upheld every lower court decision, and in the press, particularly The Hartford Courant and newspapers in the cities where the trials were held. (Newspaper accounts often demonized the litigants and their attorneys as trying to extort the cities). Though the courts always decided in the plaintiffs’ favor and against the cities, the decisions did not end stream pollution. It took a mobilized public to begin a march toward state and federal clean water statutes that have finally brought our state’s rivers back to life, a march that nevertheless began with the disgusted farmers and millowners of the 1890s.

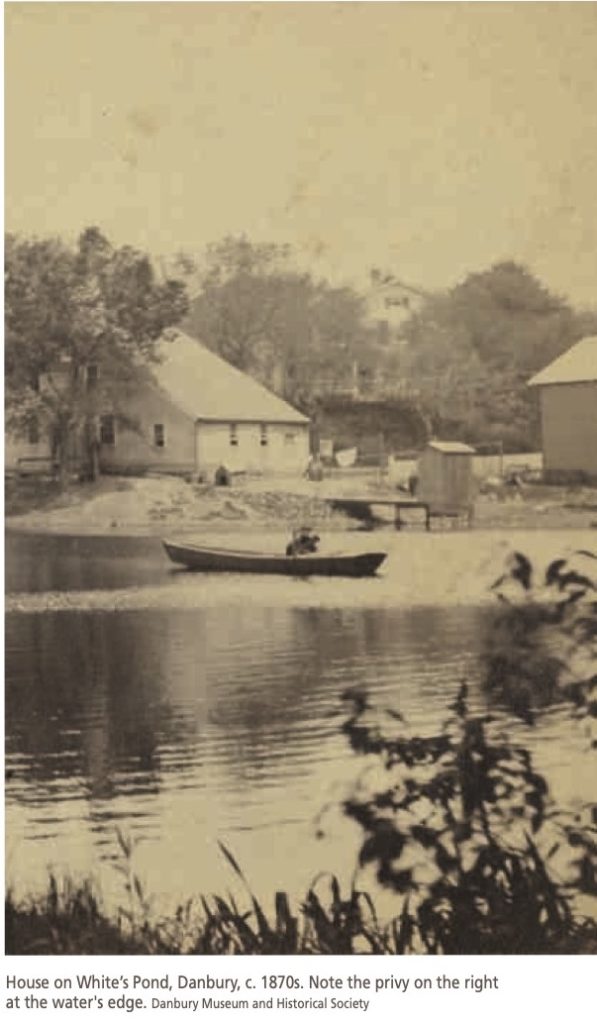

House on White’s Pond, Danbury, c. 1870s. Note the privy on the right at the water’s edge. Danbury Museum and Historical Society

The Origins of Stream Pollution

The industrial revolution brought prosperity to Connecticut, but at a high cost to its waters. By 1886 City of New Haven health officer S.W. Williston reported to the Connecticut General Assembly that, “Nearly every stream adapted to manufacturing requirements in the state is contaminated.”

People had flocked to Connecticut’s manufacturing cities in the years after the Civil War; by 1900 more than half of the state’s nearly one million people lived in just 13 cities. Factories, sited along watercourses for manufacturing processes or for power sources, also used them to get rid of industrial and human waste. In an era before septic systems and sewers, factories perched water closets over streams. Most town and city dwellers relied on simple cesspools and outhouses that shared their tiny urban lots with their wells or simply used the nearest stream or pond to dispose of waste.

Despite scientific acceptance of the germ theory by the 1880s, many still held the traditional belief that “miasmas,” or bad odors, caused many infectious diseases. Therefore, standing water was a health threat. Cesspools were known colloquially as “fever breeders,” a term that was partially accurate. Typhoid fever, a bacterial intestinal infection spread by contact with the fecal matter of an infected person, regularly killed more than 400 to 500 Connecticut residents every year and sickened 10 times that number, most of them of working age, according to statistics compiled by the state board of health in 1901. Among the causes of outbreaks the board reported were polluted streams used for water supply, tainted milk, oysters harvested in Long Island Sound, and, in one case, water from a polluted pond used in a factory washroom.

Public water, piped in from distant ponds, streams and reservoirs, seemed the answer to these health threats. But advances in plumbing—faucets replaced laborious hand pumps, and traps and vents helped eliminate odors and made indoor water closets popular—caused domestic water use to increase exponentially. The state board of health warned in 1903 that “cesspools thus become overtaxed,” causing wells to become polluted and producing disease-causing pools of stagnant water.

Flawed Solutions

Cities embraced sewers as the answer to this public health problem. Leading citizens such as Stamford industrialist Lockwood Towne of Yale & Towne and the Manchester Cheney brothers of the Cheney Brothers Company championed sewer systems as a hallmark of progress. Such systems were expensive, though. Early sewage treatment was limited to sand filter beds, which required large tracts of acreage, a challenge to city budgets. The Connecticut General Assembly regularly granted cities the right to use their rivers for untreated sewage instead. “The rule now as to sewage is simply to pass it along and let the law of gravity prevail over the law of health,” quipped The Hartford Courant in 1886. But this approach defied the common-law legal doctrine of riparian rights that held that a user of a stream had a right to its use unimpeded by the actions of users farther upstream.

Inland manufacturing cities experiencing explosive population growth in the late 19th century were, like Danbury, typically located in bowl-shaped valleys in hill country along sluggish or shallow rivers already polluted by industrial wastes. Williston warned in his 1886 report that “no less than eight cities and boroughs, varying in population from ten to thirty thousand, are projecting and laying down sewers to discharge into streams of moderate or small size…. The state is unprepared for summary action (while) the towns themselves resent imputations upon their right to sewer into natural watercourses.”

Concerned agencies began raising the alarm in the early 1880s. The state’s fish and game commission lamented the dwindling fish catch in the Connecticut River, musing whether “waters, so foul that fish placed in them die in fifteen minutes, can be wholesome to human lungs. …” James Bradford Olcott, a scientific farmer who developed strains of turf grass used in golf courses and who was one of the founders of the University of Connecticut, issued a call to political action in an address in Hartford to a committee of the state board of agriculture in 1886. Connecticut’s polluted rivers had become, he told his audience, “fountains of disease and death.” He blamed pollution for the state’s outflow of residents. He urged others to “Agitate! Agitate!”

These warnings fell on deaf ears in a rural-dominated state legislature that ran the state on a tight budget. Milon Pratt, a representative from rural Old Saybrook quoted in The Courant in 1896, summed up a prevailing attitude: “…the cities have drained the population from the towns, … (and) now they would drain their filth and make the towns pay for it. The cities are rich enough to find ways and means.”

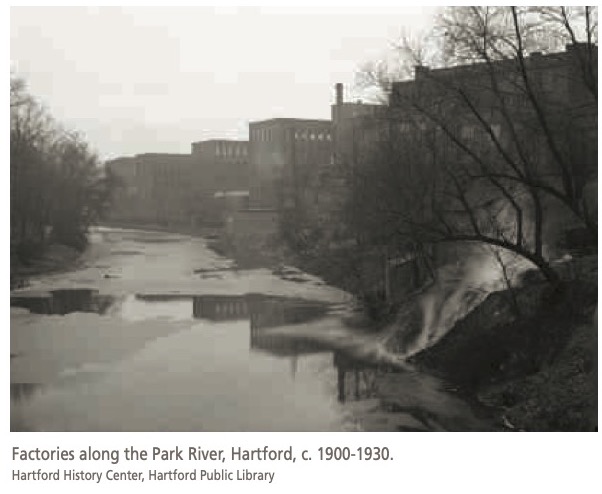

Factories along the Park River, Hartford, c. 1900-1930. Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

New Britain Faces First Suit

For McArthur and others whose livelihoods were threatened by this pollution, the only recourse was civil action in the state’s courts. New Britain faced the first of these suits, filed in 1891 by Henry Kellogg of Newington. The Hardware City had built a system of sewers that emptied into Piper’s Brook. New Britain’s sewage tripled Piper’s Brook’s volume and added a trail of sulfurous fumes as the stream flowed through Newington, into the Park River in Hartford, by the State Capitol, and ultimately into the Connecticut River.

Kellogg contended that the City of New Britain had de-valued his property without compensation, while the city argued that the general assembly had granted it that right and that the stream was already polluted by industry. Kellogg won his case, but backed away from asking for an injunction. The state supreme court upheld the decision in 1892. New Britain would eventually pay settlements to 27 property owners in Newington and New Britain. After the City of Hartford in 1899 and citizens of Middletown in 1902 sued New Britain over sewage pollution, the city cast about for a treatment site, finally settling on a field purchased in the neighboring town of Berlin. Between settlements, land acquisition, and construction costs for a treatment plant, by 1901 New Britain had spent more than a million dollars to solve its sewage problem, a small fortune for that time.

Danbury’s Case

top: Judge George Wakeman Wheeler was new to the Superior Court bench when he issued the Morgan v. Danbury decision in 1895. He served 20 years on Con- necticut’s Supreme Court, including 10 as chief jus- tice, and was considered by President Woodrow Wilson for the U.S. Supreme Court. Bridgeport Public Library bottom: Danbury News announcing the Morgan v. Danbury decision, August 3, 1895.

Encouraged by the Kellogg case, a pair of lawyers, Leonard McMahon of New Milford and Charles Murphy of Danbury, organized a group of property owners that they called an “alliance” downstream of Danbury’s sewage outfall pipe to sue the City of Danbury in 1893. Danbury had boomed in the 1880s, doubling its population, its water supply, and its number of hat factories. Its infectious-disease rate also exploded. Primitive attempts to drain crowded working-class neighborhoods through long ditches resulted in “an uncovered mass of filth and corruption … a veritable river of death to our homes,” the sewer committee of the Danbury Board of Aldermen claimed in its 1890 report. The city’s Village Improvement Society promoted sewers and paid for consulting experts. Its efforts came to fruition when the newly-chartered city government began construction of a system in 1889.

But rather than pay for the expensive measures recommended by experts, Danbury opted to wait for complaints before actually spending money on treatment. The sewers’ outfall pipe was moved to just above Beaver Brook in 1893, and a deodorizing system was installed in 1894 to tamp down odors during the summer months.

Mill owners Morgan and McArthur from Danbury’s rural Beaver Brook district joined the suit, along with 40 farmers. The Town of Brookfield kicked in $600 toward legal costs. One of the cash-strapped farmers offered to pay the attorneys with a cow, according to an 1895 story in The Danbury News. Judge George Wakeman Wheeler presided over the Morgan v. Danbury case. The trial began in early 1895, a dramatic David-versus-Goliath battle reported in extensive detail by Danbury’s press. Wheeler was especially influenced by the testimony of the many farmers who he believed were “not inclined toward litigation.” He shocked the City of Danbury and the state by issuing a sweeping injunction that ordered the city to build an adequate sewage treatment plant within two years. The ruling became a frequently-cited precedent in favor of the riparian rights of downstream property owners, even over something done ostensibly for the public good.

Extending the Danbury sewer line as a result of the Morgan v. Danbury decision, 1896. Danbury Museum and Historical Society

The City of Danbury bought a farm in the Beaver Brook section of the city and built a filtration plant there, completed in 1897. It remains the site of the city’s sewage treatment plant, the subject of a Summer 2020 stunt involving comedian John Oliver. Unfortunately, the city’s troubles were not over. Beaver Brook and Brookfield residents found the plant’s odors unbearable and filed suits again in 1902, 1933, and 1947. In one of the latter cases, local lore has it that a Beaver Brook farmer lodged a protest by dumping a load of cow manure on the steps of Danbury’s City Hall.

The Connecticut Supreme Court upheld the Morgan decision and that in a similar case involving New Britain in 1896, finally prodding the state legislature into action. In 1897 newly-elected Governor Lorrin A. Cook called for a state sewage commission to assist cities in planning sewage treatment. The commission worked until 1902, by which time 16 Connecticut cities and towns had begun to treat their sewage and others were working on plans. Cook served on the commission after his term as governor ended.

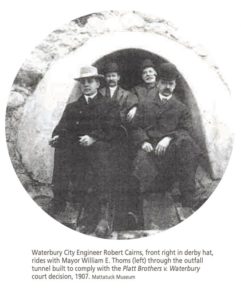

Waterbury City Engineer Robert Cairns, front right in derby hat, rides with Mayor William E. Thoms (left) through the outfall tunnel built to comply with the Platt Brothers v. Waterbury court decision, 1907. Mattatuck Museum

Waterbury Fails to Act

But all was not smooth sailing. Waterbury, after a decade of litigation in the 1890s, quietly defied the courts again and again. Waterbury presented a perfect storm of challenges to dealing with pollution, starting with hilly terrain and the Naugatuck River, a fast-running but shallow tributary of the Housatonic River that had low summer flow. By the 1890s the river was the most egregious example of stream pollution in the state, running a gauntlet of dams and burgeoning industrial cities for over forty miles to its confluence with the Housatonic in Shelton.

A typhoid outbreak in 1882 had frightened Waterbury’s parsimonious voters into building sewers emptying into the Naugatuck River. The Platt Brothers & Company, manufacturers of brass eyelets, purchased a mill site on the Naugatuck just above the city’s southern line to relocate their factory in the early 1890s. After one brother died of typhoid and the city ignored pleas to deal with sewage pollution in the river, the surviving brothers sued the city in 1891. Reportedly backed by Naugatuck millionaire Robert H. Whittemore, according to the Waterbury Herald, the Platts fought the city in the courts for 12 years. No fewer than three state supreme court decisions ruled on different aspects of the case. The city filed novel defenses that were dismissed by Judge George Wheeler and at one point attempted to seize the Platts’ land through eminent domain. Judge William Hamersley, who presided over the main part of the case, issued a less-sweeping decision than Wheeler had in the Morgan case. Waterbury was ordered to pay annual damages to the Platts and refrain from polluting the Naugatuck River during the months of low flow between June and December.

Meanwhile, Waterbury grew into the state’s fourth largest city by the turn of the 20th century, according to the U.S. Census. Ideas for massive trunk sewers stretching for miles to the south were rejected as too costly. Waterbury City Engineer Robert Cairns, who’d been secretary and technical expert for the short-lived state sewage commission, tried to comply with the court order by designing an ambitious filtration plant near the Platt Brothers site. Construction began, but an appropriation for the treatment plant itself was never authorized. Platt Brothers continued to receive annual payments from the city, and Waterbury continued to dodge treating its sewage until 1951. Other cities, like Torrington to its north, also settled pollution lawsuits rather than build treatment plants.

The Public Demands Action

The issue came roaring back in the Progressive Era. “The Connecticut public have been in a Rip Van Winkle sleep upon the subject of these great natural privileges of the people, …” wrote Stratford State Representative Stiles Judson in a letter to the Bridgeport Farmer on May 6, 1913. As John Cumbler explains in Reasonable Use: The People, the Environment, and the State, New England 1790-1930 (Oxford University Press, 2001), an expanded middle class began to look to nearby waters for recreation. The press and public officials began talking about clean streams as a natural right. In 1913 backers of Judson’s anti-pollution bill marshaled widespread public support for the first time, from state fish and game clubs to the National Grange, in an abortive (it was watered down and failed) effort to fulfill the state board of health’s long campaign for full jurisdiction over the state’s waters.

After further surveys of the state’s rivers found them polluted and lifeless, in 1925 the Connecticut General Assembly finally established a water board (later renamed the Water Resources Commission and a forerunner of today’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection, or DEEP) that had the power to issue permits for discharges into the state’s waters, including both municipal sewage and industrial waste. Federal and state aid eased the financial burden on municipalities, and—over time—increasingly sophisticated levels of treatment became available.

By 1963 Connecticut Life magazine reported that 90 percent of the state’s sewage and 40 percent of its industrial waste was being treated. A state clean water act passed in 1967 established a rating system for uses permissible in waters based on their level of pollution. This system, and the act in general, became a model for the federal Clean Water Act passed in 1972, a fact proudly touted on the DEEP website.

The water pollution crisis of the 1880s and 1890s was arguably the state’s first modern environmental issue. The episode brought home for the first time to lawmakers, public officials, and citizens that natural systems like rivers were interconnected and transcended political boundaries. The idea that there were legal limits to cities’ ability to act with impunity as “little republics” became widely accepted. Despite the many setbacks along the way, the state has long been proud of its progressive record on clean water. Today, once-polluted streams like the Still, the Naugatuck, and the Mattabesset are fishable and boatable. The forgotten millowners and farmers of the 1890s who fought powerful cities in the courts laid the legal foundation that made that outcome possible.

William Devlin was a history teacher, an adjunct instructor of geography at Western Connecticut State University and is the author of books and articles about Danbury area history. He has been a longtime volunteer for environmental causes. This story is based on his longer paper for the Spring 2020 issue of Connecticut History Review.