(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2018

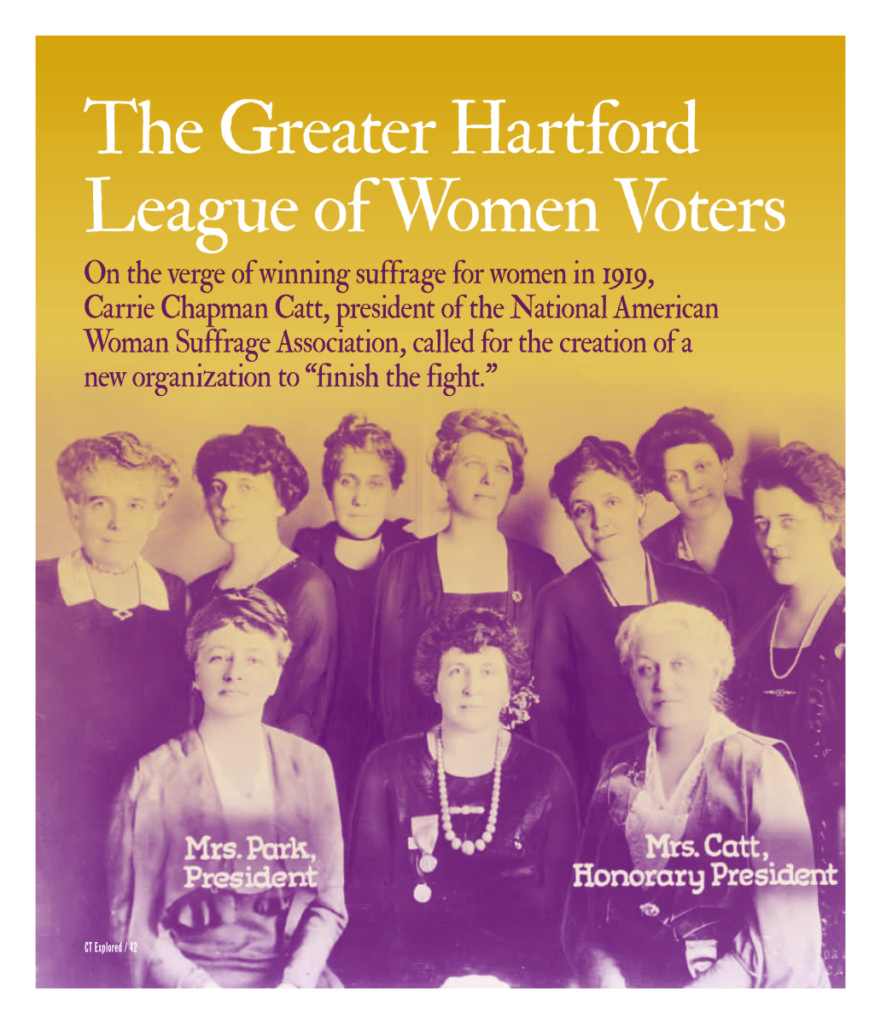

On the verge of winning suffrage for women in 1919, Carrie Chapman Catt, president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, called for the creation of a new organization to “finish the fight.” The League of Women Voters would organize at the state level to urge ratification of the 19th amendment to the U.S. Constitution, end legal discrimination against women, and help the country rebuild after World War I. In Catt’s view, the league would help women find a political voice as they finally joined men as equal citizens, learning to participate in party politics, and bringing their unique perspective to public policy. She envisioned that this would take about five years. Almost 100 years later the league still plays an important role in the world of politics in Connecticut and across the nation.

The idea of an organization for women voters seemed strange to those who wondered whose interests such a group would serve. Initially both Republicans and Democrats criticized the league as favoring the other party, while some suspected it was an effort to start a new political party just for women. The league itself insisted it was strictly nonpartisan, encouraging its members to get involved in the political party of their choice. Throughout its early years the league advanced an idealized view of what was then called “intelligent” women’s citizenship, one that would base its actions on research and expert knowledge of issues. Women—still on the outside of the political world—would lobby for the common good rather than try to exercise political muscle as a voting bloc.

The idea of an organization for women voters seemed strange to those who wondered whose interests such a group would serve. Initially both Republicans and Democrats criticized the league as favoring the other party, while some suspected it was an effort to start a new political party just for women. The league itself insisted it was strictly nonpartisan, encouraging its members to get involved in the political party of their choice. Throughout its early years the league advanced an idealized view of what was then called “intelligent” women’s citizenship, one that would base its actions on research and expert knowledge of issues. Women—still on the outside of the political world—would lobby for the common good rather than try to exercise political muscle as a voting bloc.

Connecticut was the last state to organize a League of Women Voters, perhaps because suffrage activists spent their energies immediately after the amendment was ratified opposing (unsuccessfully) the re-election of their legislative foe, Connecticut’s U.S. Senator Frank Brandegee. (See “Senator Brandegee Stonewalls Women’s Suffrage,” Spring 2016.)

Katherine Ludington of Old Lyme (top photo: back row, far left) was a leader of the effort to found a state league. She was a member of the League of Women Voters national board, had cultivated relationships with Republican lawmakers during her years advocating for suffrage in Connecticut, and moved comfortably in political circles. She was part of the league committee that presented the first “women’s platform” to Republican and Democratic convention committees in 1920, with planks representing reform causes such as banning child labor, providing federal aid to education, promoting women’s employment, and making women’s citizenship status separate from that of their husbands.

Late in organizing at the state level, the Connecticut league grew quickly. Having started in January 1921 with a meeting of 200 women in New Haven, by the end of the year there were local leagues in 32 Connecticut towns, a statewide membership of more than 3,000 women, and county-wide organizing in seven of the state’s eight counties.

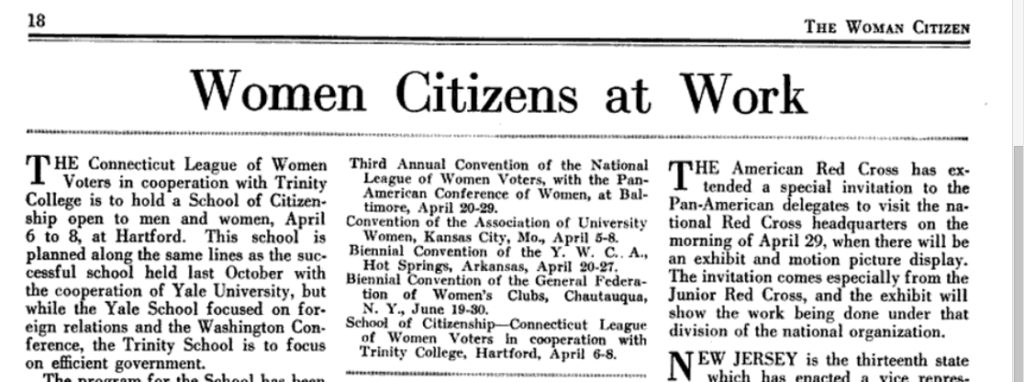

The idea that women’s intelligence and moral influence would benefit local, state, and national politics carried over from suffrage organizing into the state league’s program and mode of operation. In fact, Connecticut’s suffrage organization had placed significant emphasis on educating women for citizenship as early as the 1890s. They had created citizenship schools to teach public speaking and parliamentary law to new members, making it a training ground for emerging leaders. The Connecticut League of Women Voters continued this emphasis in the 1920s; its first initiative was conducting a series of citizenship schools in conjunction with Yale University, where (as a 1953 history of the state league recounted) “eminent men” lectured the women about the machinery of government, proposals for social reform, and international relations.

What would it mean for women to become full citizens? Nationally, the league’s early years were marked by a dual emphasis on citizenship skills and social reform. It proposed legislation on issues such as child labor, maternal and infant health, funding for education, and equalizing women’s legal status. As it became clear later in the 1920s that women were not going to vote as a bloc—and as conservatives decried some of the women’s legislative priorities as socialist—the league proceeded more cautiously, and moved toward less controversial, “good government” reforms. In Connecticut, the league’s newsletter removed the word “woman” from its name in 1939, becoming the Connecticut Voters Bulletin.

In its early years the West Hartford League of Women Voters (now known as the Greater Hartford league) was noted for its campaign to recruit new women as voters. Mrs. Ivar (first name unknown)

Emily Sophie Brown of Naugatuck was one of the first five women elected to the Connecticut legislature in 1920. The Woman Citizen, July 30, 1921

Lundgaard won a contest sponsored by Woman’s Home Companion magazine in 1924 for imaginative solutions to the problem of getting more women to use their new right to vote. The league organized a motor corps to transport women to register as voters, assigning each member a quota of the town’s 2,000 women who were eligible to become voters. They used postcards, advertising, banners, and posters to publicize the campaign, which registered 940 new voters out of West Hartford’s population of 9,000, resulting in a record-breaking vote at the town election. A 1924 article in The Hartford Courant noted, “This movement is on a purely non-partisan basis and the attempt will be made to waken the women to their civic responsibilities.”

From the beginning, the Connecticut league focused on women’s jury service, an aspect of citizenship from which women were excluded. The league doggedly pursued this issue for 16 years. The jury service bill it wrote was eventually included in the Democratic Party’s platform. League members lobbied legislators and even the wives of legislators, made plans for a test case to bring to court, and also went to observe courtrooms to determine if these proceedings were, as opponents claimed, unfit for women’s ears. They recruited women who were experts in various fields to speak before the recalcitrant Judiciary Committee and consulted with Wilbur Cross, who was dean of Yale’s graduate school. When he became governor, he proposed his own jury service bill, which finally became law in 1937.

From the 1930s through the 1950s, the Connecticut League of Women Voters advocated modernizing the state constitution and making changes to improve the administration of government. It recommended a direct primary, mandatory redistricting of the state senate, reducing the size of the general assembly to one member from each town, eliminating county government, and creating a unified district court system. In 1951 it called for a constitutional convention, which did not come about until 1965. Concern about equity in political representation was carried to court by West Hartford league member Miriam Butterworth and her husband Oliver Butterworth. The Butterworth v. Dempsey case, upheld by the U.S. Supreme Court in 1964, led to a new state constitution, with a new method of apportioning legislators, in 1965. (See “Reflections on the 1965 Constitution,” Summer 2014.)

In the years before the resurgence of the women’s movement, the league’s careful approach to politics made it a socially acceptable outlet for educated women in Connecticut. In the mid-1950s, Shelagh O’Neill, who had recently moved to West Hartford, was invited to a West Hartford league meeting. She recalled (looking back for the league’s 75th anniversary in 1998) being “dazzled” by “intelligent women saying worthwhile things,” including responses to the charge by Senator Joseph McCarthy that the league was a “pinko” organization. In response to McCarthyism, the West Hartford league had decided to study issues of civil liberties. The local newspaper commended the “ladies of the League” for tackling fundamental questions in their discussions of freedom of speech and of the press, loyalty programs, congressional investigations, and the Bill of Rights. Over the years, the West Hartford group also studied and advocated for more local issues, from town planning and school facilities to fair housing and energy conservation. In 1998 it changed its name to the Greater Hartford League of Women Voters, recognizing that its interests and members involved the whole region.

Although the league’s own activities nationally and locally were nonpartisan, a number of women found it to be a route into partisan politics—including Ella Grasso, who in 1975 became the first woman in the nation to be elected governor in her own right. Grasso called her involvement in the League of Women Voters “the best internship possible for an aspiring politician.” In fact, it was her fellow league members who, in 1943, suggested that she join a political party, spurring her to become a Democratic Party speechwriter and later a legislator. In West Hartford, all the early women elected to town offices came to public service through the league, including the first female members of the town council (1929) and the board of education (1932). League member Louise Duffy ran for the state senate in 1924, campaigning on her support for a child labor amendment. She got involved with Democratic Party politics statewide and later served on the West Hartford Board of Education and on the town’s library board. Fifty years later the league provided a similar pathway for Katie Reynolds, who was elected mayor of West Hartford in 1973. Nan Streeter, who succeeded her as mayor, noted that in her circles in West Hartford, the league was “the one place where you don’t know how many children people have.”

In recent decades, the League of Women Voters—which opened its membership to men in 1974—has been known less as a women’s organization than for its work educating all voters, promoting voter registration and knowledge about public policy issues. Its legacy of encouraging informed and active citizenship is no less important in Connecticut today than it was at the league’s founding.

Elizabeth Rose is library director for the Fairfield Museum. She last wrote “Site Lines: Birdcraft,” Fall 2017.

This is the third in a series of stories about the history of nonprofits in the Greater Hartford region, funded in part by the Hartford Foundation for Public Giving.