By Christopher A. Griffin and Henry S. Cohn

(c) Connecticut Explored, Spring 2016

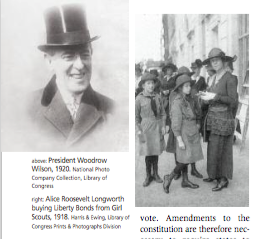

Frank B. Brandegee of New London served in the United States Senate from 1905 until his suicide in 1924. During his time in the nation’s capital, Brandegee developed close friendships with many national political figures and even some of Washington’s more notable residents at the time, including Alice Roosevelt Longworth, the oldest daughter of President Theodore Roosevelt and wife of Congressman Nicholas Longworth. Although Brandegee was relatively quiet politically during his early years in the U.S. Senate, he eventually grew into an outspoken and conservative opponent of the major progressive legislative movements of the 1910s and 1920s. His fights against the League of Nations and the 19th Amendment are the most prominent aspects of his political career.

Brandegee was born on July 8, 1864 into an established New London family. In a memorial address in honor Brandegee given after his death, college classmate and fellow Senator George McLean described Brandegee’s mother, Nancy Brandegee, as a “good New England mother,” and his father, Augustus Brandegee, as a popular lawyer and politician. At the time of Frank’s birth, his father was serving Connecticut in the U.S. House of Representatives, and he was a friend of President Lincoln.

As a child, Frank Brandegee enjoyed all that the southern New England countryside had to offer. He spent much of his free time in the woods. A lover of animals, he found a curious hobby in trying to make pets of wild creatures, including, according to McLean one “very affectionate but utterly untrustworthy raccoon.” Although as a senator Brandegee would serve as chair of the Committee on Forest Reservations and Protection of Game and helped to pass legislation protecting the Appalachian Mountain Reservation, he expressed regret later in life that his political career prevented him from spending more time outdoors.

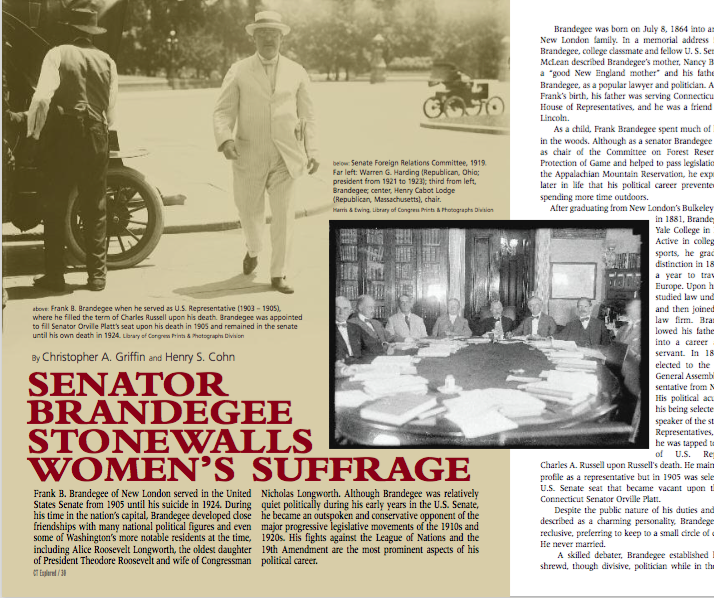

After graduating from New London’s Bulkeley High School in 1881, Brandegee attended Yale College in New Haven. Active in college clubs and sports, he graduated with distinction in 1885 and took a year to travel through Europe. Upon his return, he studied law under his father and then joined his father’s law firm. Brandegee followed his father’s footsteps into a career as a public servant. In 1888 he was elected to the Connecticut General Assembly as a representative from New London. His political acumen led to his being selected to serve as speaker of the state House of Representatives, and in 1903 he was tapped to fill the seat of U.S. Representative Charles A. Russell upon Russell’s death. He maintained a low profile as a representative but in 1905 was selected to fill a U.S. Senate seat that became vacant upon the death of Connecticut Senator Orville Platt.

After graduating from New London’s Bulkeley High School in 1881, Brandegee attended Yale College in New Haven. Active in college clubs and sports, he graduated with distinction in 1885 and took a year to travel through Europe. Upon his return, he studied law under his father and then joined his father’s law firm. Brandegee followed his father’s footsteps into a career as a public servant. In 1888 he was elected to the Connecticut General Assembly as a representative from New London. His political acumen led to his being selected to serve as speaker of the state House of Representatives, and in 1903 he was tapped to fill the seat of U.S. Representative Charles A. Russell upon Russell’s death. He maintained a low profile as a representative but in 1905 was selected to fill a U.S. Senate seat that became vacant upon the death of Connecticut Senator Orville Platt.

Despite the public nature of his duties and what some described as a charming personality, Brandegee was fairly reclusive, preferring to keep to a small circle of close friends. He never married. Asked once by McLean why he chose not to marry, Brandegee, horrified at the thought of marriage, replied, “Young frogs would best keep out of wells.” Brandegee apparently never changed his view on marriage.

A skilled debater, Brandegee established himself as a shrewd, though divisive, politician while in the senate. He was “devastating in impromptu debate,” according to Professor and historian Herbert Janick. Fellow senator McLean remarked that he had “flashes of genius rather hard to describe.” A fierce opponent of progressive legislation, Brandegee often found himself in opposition, running against the tide of reform (perhaps unsurprising for a senator representing “the land of steady habits”).

His views regarding international affairs were informed by a fierce nationalism. As a conservative leader in the U.S. Senate, Brandegee helped direct a successful campaign to derail President Wilson’s signature foreign policy initiative—U.S. participation in the League of Nations—principally because Brandegee feared it would dilute national sovereignty. Brandegee banded together with other Republican and Democratic senators opposed to participation to form a group that became known as the “irreconcilables.” Working closely with Alice Roosevelt Longworth (who was actively involved behind the scenes in Republican politics), Brandegee and the irreconcilables maneuvered to block attempts at compromise, preventing supporters from attaining the votes needed to ratify the Treaty of Versailles and join the League of Nations. The efforts of Brandegee and the irreconcilables are memorialized in Longworth’s memoir Crowded Hours (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1933) and are featured in Gore Vidal’s fictional account of the 1920’s, Hollywood.

In domestic affairs, Brandegee was decidedly anti-nationalist and in favor of local control, fearing that federal bureaucracies were gaining too much power and were becoming a menace to the people. He opposed federal anti-child-labor legislation on the ground that it unconstitutionally interfered with the states’ power to regulate labor. (The Supreme Court agreed with Brandegee’s position on the validity of the legislation and struck it down, though the court reversed itself decades later.) As the prohibition wave swept the nation, Brandegee—who suffered from alcoholism, according Lewis Gould, author of The Most Exclusive Club: A History of the Modern United States Senate—opposed any federal interference with state liquor regulation. And Brandegee staunchly opposed the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote.

In domestic affairs, Brandegee was decidedly anti-nationalist and in favor of local control, fearing that federal bureaucracies were gaining too much power and were becoming a menace to the people. He opposed federal anti-child-labor legislation on the ground that it unconstitutionally interfered with the states’ power to regulate labor. (The Supreme Court agreed with Brandegee’s position on the validity of the legislation and struck it down, though the court reversed itself decades later.) As the prohibition wave swept the nation, Brandegee—who suffered from alcoholism, according Lewis Gould, author of The Most Exclusive Club: A History of the Modern United States Senate—opposed any federal interference with state liquor regulation. And Brandegee staunchly opposed the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote.

The women’s suffrage movement in the United States began to take hold shortly before the Civil War and reached a peak in the 1910s. [See “The Long and Bumpy Road to Women’s Suffrage,” page 24,] The United States Constitution generally leaves to the states the power to decide who may vote. Amendments to the constitution are therefore necessary to require states to guarantee the right to vote to those disenfranchised under state law. The 15th Amendment, passed by the U.S. Congress in the final days of the Civil War and ratified by the states in 1870, guaranteed the right to all citizens regardless of their race, but it did not address gender. By the time of the passage and ratification of the 15th Amendment the women’s suffrage movement was gaining national steam. Advocates tried to add to the amendment a guarantee to women of the right to vote, but the effort failed. Women’s suffrage advocates then took their fight to the states.

Two advocacy organizations were formed in 1869, and advocates persuaded new states joining the union from the western frontier to grant women the right to vote. Still short of achieving the goal of ensuring that every woman the United States could cast a ballot, advocacy groups aimed their efforts in the 1900s at an amendment to the United States Constitution. The progressive movement added to the momentum, with Theodore Roosevelt’s Progressive Party formally endorsing women’s suffrage in its 1912 platform. When the United States entered World War I, women took a greater role on the home front, including taking on employment traditionally reserved for men. Their more prominent role in affairs outside the home brought the suffrage issue to the forefront of national politics. Advocacy groups convinced the United States House of Representatives in 1918 to adopt an amendment to the constitution, and the battle for the vote moved to the United States Senate.

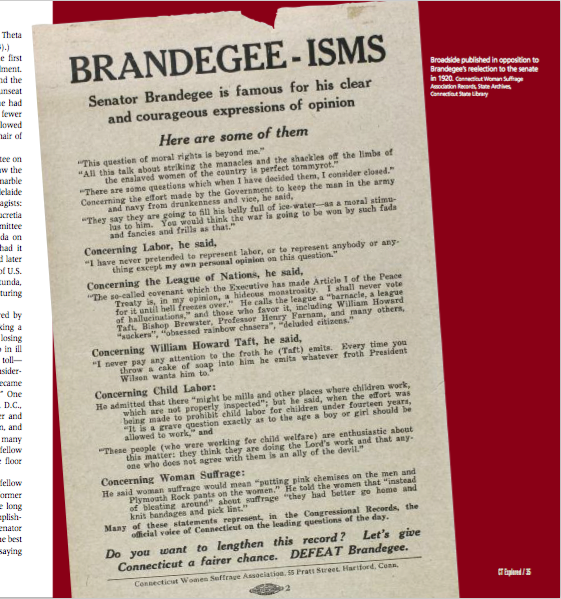

During the senate’s debates on the suffrage amendment, Brandegee was an outspoken opponent. In his anti-federalist opinion, matters of suffrage were for the states, not the federal government, to regulate. Widely condemned by suffrage organizations for his opposition to a federal amendment, he refused for years even to meet with suffrage supporters from his home state of Connecticut, telling them his mind was closed on the issue.

During the senate’s debates on the suffrage amendment, Brandegee was an outspoken opponent. In his anti-federalist opinion, matters of suffrage were for the states, not the federal government, to regulate. Widely condemned by suffrage organizations for his opposition to a federal amendment, he refused for years even to meet with suffrage supporters from his home state of Connecticut, telling them his mind was closed on the issue.

In May 1918, as World War I raged in Europe, Brandegee took to the floor of the senate to express his belief that prohibition and women’s suffrage were distractions from the war effort. According to the Congressional Record (Volume LVI), he said:

You cannot win this war by talking about woman suffrage and prohibition. We won every war we ever were in without woman suffrage and prohibition. We won the Wars of 1776 and 1812 and the Mexican War and the War of 1860 and the Spanish-American war, and there were no pink-tea parties talking about putting pink chemises on the men and Plymouth Rock pants on the women. The women do not propose to go over in the trenches abroad and do the fighting. It is the men who have got to do that. Instead of bleating around here about their saving democracy by forcing their way into caucuses and conventions, they had better go home and knit bandages and pick lint and get ready to take care of their brothers and sons and fathers who are going to be shot to pieces in the trenches abroad.

When fellow Republican Senator Jacob Gallinger of New Hampshire interrupted Brandegee to remind him that the nation’s women were already doing “that very thing to an extent that they ought to be congratulated upon,” Brandegee replied, “I do congratulate them to the extent they are doing it; but if they would get out of this lobby and go back and do more of it, I should be better pleased with them.” One wonders what Alice Longworth might have thought about statements like these from Brandegee. According to her biographer, Stacy A. Cordery, Longworth was active in the Republic Women’s National Committee, and she noted in her memoir that she had “always believed that women should have the vote.”

Not intimidated by Brandegee’s acerbic rhetoric, local suffrage supporters countered with harsh criticism of their own. According to a July 13, 1918 Hartford Courant article, suffrage supporters held a pro-suffrage rally in Hartford the day before, taking the occasion to hurl personal jabs at Senator Brandegee. One speaker, Lillian Ascough, chairwoman of the National Women’s Party in Connecticut, compared Brandegee’s mind to an antique from an earlier era: “interesting to observe, but not for present day use.”

Despite growing national support for the proposed amendment, the U.S. Senate rejected it in September 1918 and again in February 1919, when it fell only one vote shy of passage. Undeterred, supporters in the senate brought the proposed amendment up for a third vote and, finally, on June 4, 1919, the senate decisively approved the measure by a vote of 56 to 25. Brandegee consistently voted against it. Congress sent the amendment to the states for ratification or rejection, with the approval of 36 states (or three-fourths of the then-48 states) required to make the proposed amendment part of the constitution. Suffragists took their fight back to the states once more and quickly began persuading their states to adopt the amendment with hopes that it would be approved in time for women to vote in the 1920 presidential election.

Brandegee sensed that political momentum had begun to favor the amendment. Up for reelection in 1920, he also recognized the potential effect that a new voting constituency of women might have on his chances for keeping his senate seat. On March 10, 1920—less than one year after the senate’s approval—West Virginia became the 34th state to ratify the amendment, with many states, including Connecticut, having yet to consider it. The following day, March 11, 1920, Brandegee’s harsh resolve against the amendment began to show signs of weakening. He acknowledged to Helena Hill Weed, a representative from the National Women’s Party from Norwalk, that ratification was inevitable and that further resistance to the suffrage movement was likely futile. The State of Washington gave its approbation to the amendment a few days later, and on August 18, 1920 Tennessee became the 36th state to ratify the amendment. Connecticut’s legislature had adjourned in May 1919 and was not due to reconvene until January 1921.

Political maneuvering in Tennessee concerning its ratification vote cast doubt on its validity, giving new importance to Connecticut’s vote. Governor Marcus Holcombe had resisted calling a special session but relented in September 1920. With women inevitably about to become part of Brandegee’s voting constituency in time for the 1920 election, Brandegee grasped for an opportunity to reconcile with his former opponents. The Connecticut General Assembly convened in special session on September 14 and proceeded to consider the amendment. On the eve of the session, Brandegee dispatched a letter to Colonel Isaac Ullman, chair of the Connecticut Men’s Ratification League, urging ratification. In what The New York Times labeled an “argument of expediency,” Brandegee wrote:

In view of the fact that the validity of the ratification of the amendment by the State of Tennessee has been questioned and that the result of the entire election throughout the country may be imperiled thereby, and in consideration of the fact that the amendment is certain to be ratified by more than the required number of States as soon as their Legislatures assemble in 1921, I earnestly hope that the Legislature of Connecticut will ratify it.

The Connecticut General Assembly ratified the amendment. Because of some questions about the validity of the special session, the governor called another session, and Connecticut ratified the amendment again on September 21. Tennessee’s original vote was also deemed valid, though, providing more than enough support needed to make the 19th Amendment officially part of the United States Constitution in time for women to vote in the 1920 elections. Although the fight for a women’s suffrage amendment was over, the fight for Brandegee’s senate seat was just beginning.

Brandegee’s concern about a backlash from women voters proved well founded. Local suffrage associations shifted their attention from gaining women the right to vote to influencing how newly enfranchised women should exercise that right. Largely supporting Warren Harding and the Republican ticket, suffrage associations nevertheless turned against Brandegee, also a Republican. The Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association made removing Brandegee from office its last official mission. Painting him as backward and out of touch with Connecticut voters, anti-Brandegee groups lambasted him for his opposition to federal anti-child labor legislation, his fight against the League of Nations, and his refusal to support legislation that would bar serving liquor to soldiers and sailors during war. Opposing Brandegee but not wanting to erode support for other Republican candidates, including Harding, election flyers expressly urged voters to split the Republican ticket by voting for all of the Republican candidates except Brandegee, with the admonishment “Don’t be Afraid . . . Split it!”

Brandegee’s concern about a backlash from women voters proved well founded. Local suffrage associations shifted their attention from gaining women the right to vote to influencing how newly enfranchised women should exercise that right. Largely supporting Warren Harding and the Republican ticket, suffrage associations nevertheless turned against Brandegee, also a Republican. The Connecticut Women’s Suffrage Association made removing Brandegee from office its last official mission. Painting him as backward and out of touch with Connecticut voters, anti-Brandegee groups lambasted him for his opposition to federal anti-child labor legislation, his fight against the League of Nations, and his refusal to support legislation that would bar serving liquor to soldiers and sailors during war. Opposing Brandegee but not wanting to erode support for other Republican candidates, including Harding, election flyers expressly urged voters to split the Republican ticket by voting for all of the Republican candidates except Brandegee, with the admonishment “Don’t be Afraid . . . Split it!”

The Republican establishment, firmly supporting Brandegee, responded forcefully to keep the Republican vote behind Brandegee (and the rest of the Republican ticket, for that matter). Reaching out directly to women voters, flyers warned them not to be swayed by “Unfair and Unprincipled Attacks” on Brandegee and reminded them of the usefulness of Brandegee’s seniority in the U.S. Senate (which can lead to more powerful leadership positions, and thus more influence for Connecticut). (A detailed description of Brandegee’s reelection fight by historian and professor Herbert Janick appears in The Historian (Phi Alpha Theta National History Honor Society, Vol. 35, # 3, May 1973).)

On election day in November 1920, women nationwide voted in the first national election after the passage of the 19th amendment. Connecticut voters overwhelmingly backed Harding and the Republicans, and despite the suffragists’ campaign to unseat Brandegee, he won another term in office. Though he had ridden a pro-Harding wave to victory, he received far fewer votes than Harding in Connecticut. Yet his seniority allowed him to occupy powerful positions, including that of chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

Brandegee also served as chair of the Joint Committee on the Library in 1921 when, in an ironic twist, he oversaw the disposition of a gift to the U.S. Capitol building: a marble tribute to the suffrage movement. The sculpture by Adelaide Johnson featured busts of three prominent suffragists: Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Lucretia Mott. Brandegee and the rest of the all-male committee accepted the gift in a ceremony in the capitol rotunda on February 15, 1921. Two days later, the committee had it removed to a storage area in the capitol basement, and later to the crypt. It remained there until 1997 when an act of U.S. Congress returned the monument to the capitol rotunda, where it is now on display alongside monuments featuring Abraham Lincoln and Martin Luther King.

Brandegee’s final years in the senate were marred by personal troubles. Although skilled at political maneuvering, Brandegee proved a failure in managing his personal finances. He fell deeply into debt after making a number of bad real estate investments. His creditors, losing patience with him, pushed for payment. He was also in ill health. Years of depression and drink had taken their toll—McLean remarked that Brandegee was “suffering considerable physical and mental distress,” and as his ailments became more severe, felt that he “had gone never to return.” One evening in October 1924, at his home in Washington, D.C., Brandegee left a note and some money for his driver and house servants, locked himself in his upstairs bathroom, and ended his life by inhaling toxic heating gas. Although aware of his suffering, some of his fellow senators and representatives expressed on the senate floor that his premature death caught them by surprise. An anonymous source later suggested to a U.S. Senate committee that his death was a murder, though those allegations were never proven.

In a poignant series of memorial addresses, his fellow senators and representatives, including some of his former opponents, put aside their differences with Brandegee long enough to laude his skills as a legislator and his accomplishments for his causes. Brandegee’s fellow senator from Connecticut, George McLean, provided perhaps the best and most succinct explanation for Brandegee’s politics, saying simply that Brandegee “loved the word ‘no.’”

Christopher A. Griffin is an attorney and serves as a judicial clerk for the Justices of the Connecticut Supreme Court. Henry S. Cohn is a former judge of the Connecticut Superior Court and presently serves as a Judge Trial Referee.

Read more about women’s suffrage here.

Listen to a Grating the Nutmeg podcast segment: “Theodate’s Suffrage Journey” with Melanie Anderson Bourbeau of Hill-Stead Museum here.