By Alexandra Maravel

Do you remember the rush of looking out an airplane window for the first time? Perhaps a night landing made a city’s lights as breathtaking as the Milky Way in a dark sky. Now remember your first impression of a “great” work of art. Perhaps it was a Hudson River School painting at the Wadsworth Atheneum. A George Catlin portrait of a Native American man at the New Britain Museum of Art. Mary Cassatt at the Hill-Stead. A Georgia O’Keefe or Faith Ringgold print at Yale that offered a new perspective on the world that you know. Yvonne Jacquette’s aerial paintings deliver that same thrill of discovery.

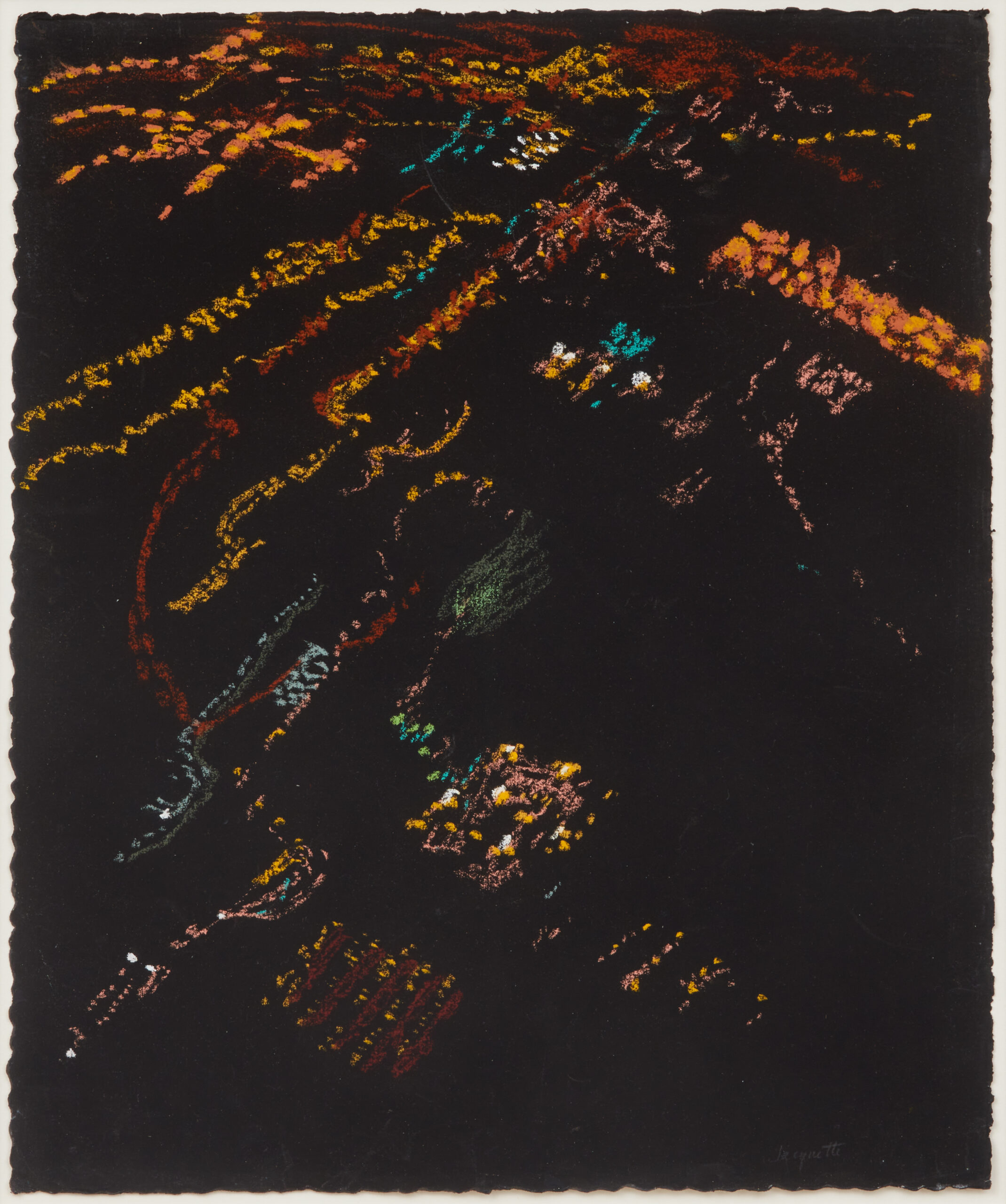

Night Lights, Reclining Plane I, 2007 Pastel on paper 17 x 14 inches. © The Estate of Yvonne Jacquette. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York.

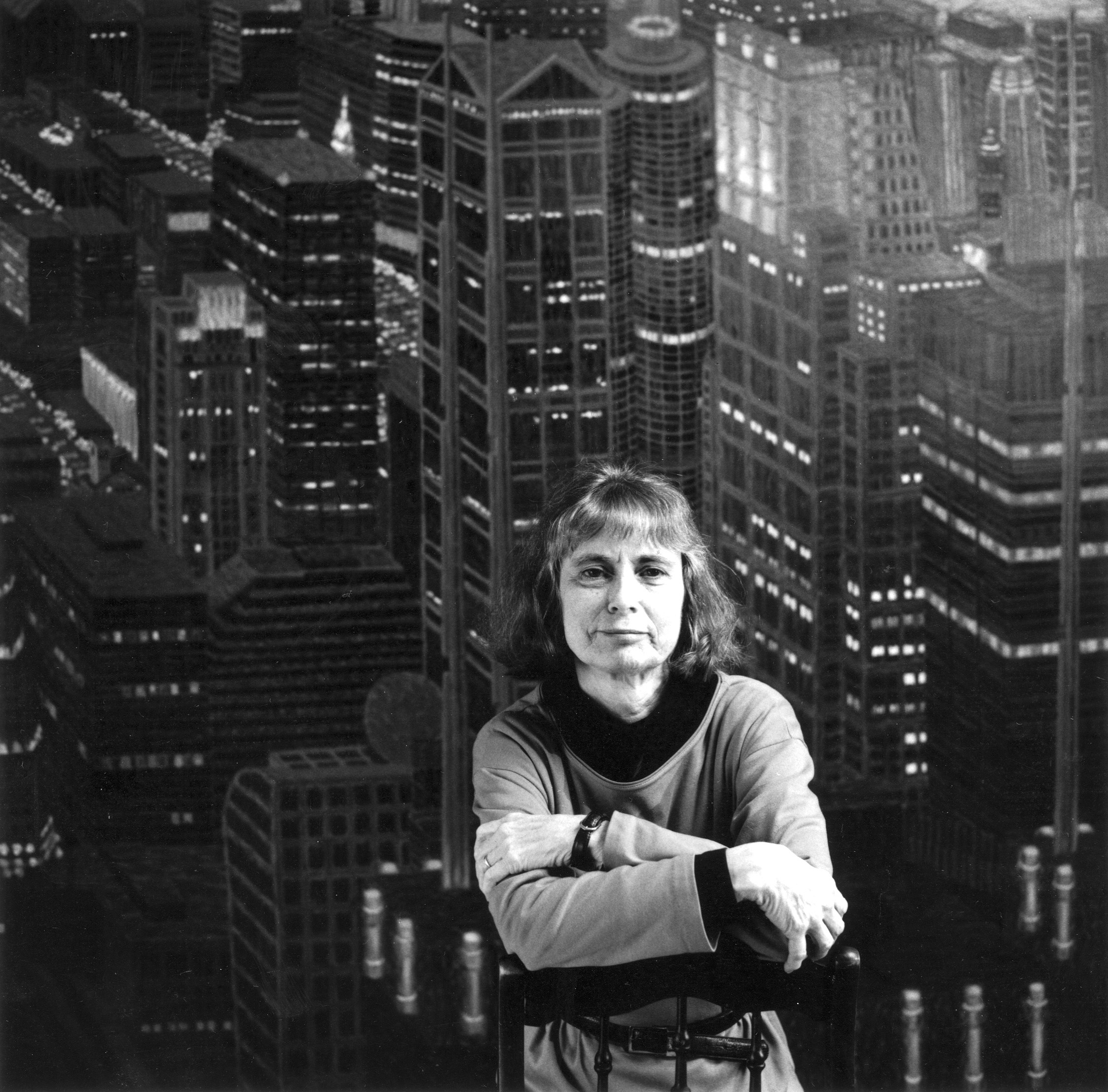

Jacquette’s path to national and even international acclaim began in Connecticut. Born in 1934 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, she was raised in Stamford. According to the 1950 US Census, William and Helen Jacquette lived on Sagamore Road with their seven children. In “Canaletto of the Skies,” a September 4, 2003, Artcritical interview with David Cohen, Jacquette said she had studied privately as a teen with Robert Roché, an art teacher at Stamford High School who had worked under John Sloan, the renowned New York artist and activist. A February 18, 1951, article in The Hartford Courant listed Jacquette and Roché among students and their teachers whose works would appear in an exhibition at the Wadsworth as part of an annual, countrywide student art contest. On May 4, 1952, The Courant reported that the 17-year-old Jacquette was a co-winner of that year’s Scholastic Art Awards competition, a national honor that helped launch the young artist’s career.

Shopping Mall, Rockland, ME II, 2003 Oil on canvas 46 x 55 1/8 inches.

© The Estate of Yvonne Jacquette. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York.

As noted on the website of DC Moore, the New York gallery that represented her, Jacquette attended the Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). It was there, she told David Cohen, that she turned away from Roché, who had wanted her to be his apprentice. She then moved to New York City, arguably the epicenter of the art world at the time. At RISD and in New York, Jacquette was exposed to a new world of 20th-century modern art. She and her husband, photographer Rudy Burckhardt, bought a summer place among artists in Maine in 1965, according to her May 3, 2023, obituary in The New York Times. There, she took to the skies to sketch, beginning a process and practice that transformed her enormous talent into a unique vision through aerial perspective.

Lawry Pond Basin, 1976 Oil on linen 60 x 44 inches.

© The Estate of Yvonne Jacquette. Courtesy of DC Moore Gallery, New York.

Consider the lovely, pointillist texture of Lawry Pond Basin. Now look at the stark, dizzying, monochromatic perspective of Vertiginous World Financial Center III. Compare the specific urban Chicago landscape of the portrait Lakeshore Drive II with the unidentifiable, abstract rivers of light and darkness in Night Lights, Reclining Plane I. Finally, take two images of Maine: Route 3 to Augusta, Maine, and Shopping Mall, Rockland, ME. The fuzzy constellation of the illuminated built environment in the former contrasts with the precise concrete substance in the latter, each piece creating its own excitement in the viewer.

Yvonne Jacquette created work that is now in the collections of over 40 museums throughout the United States, including the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Modern Art, and the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York; and the Philadelphia Museum of Art. In Connecticut, her woodcuts and other prints are found in the collections of the Yale University Art Gallery and the Davison Art Center at Wesleyan University. By the end of her long, productive life, Jacquette had turned aerial sketches of complex cities like New York, Hong Kong, Vancouver, and Chicago and rural vistas across the country into a multimedia body of work that challenged the viewer to see the world in the ever-changing ways in which she saw it.

That connection between artist and viewer is what makes art great. We can all look down from the heights of planes and tall buildings. Nowadays, we can explore satellite imagery of our planet. We can all marvel. But not everyone can take her own experience and recreate the world.

Alexandra Maravel is an adjunct professor of history at Central Connecticut State University.

Learn More!

DC Moore Gallery, New York, dcmooregallery.com/artists/yvonne-jacquette

Neil Genzlinger, “Yvonne Jacquette, 88, Who Took Her Painting to Another Level Dies,” The New York Times, May 3, 2023