(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2014-2015

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The 1960s was one of the most turbulent decades of the 20th century—and one whose legacy historians continue to debate. Ghosts of the decade are everywhere, perhaps most powerfully in the experience of war. The Vietnam War—before Afghanistan our longest—reshaped American politics and society, bequeathing us traditions of massive protest and policymakers’ desires to vanquish “Vietnam syndrome,” our collective reluctance to fight unpopular wars. The social movements of that era led to considerably more political equality in the United States today, for women, for African Americans, for Latinos, for gays and lesbians. The national celebration this year of the 50th anniversary of the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 is an important reminder of that crucial legacy.

That said, the flood tide of American liberalism reached in the late 1960s has done little but recede since then, as a newly resurgent American conservatism, reborn after its stinging defeat in 1964, not only carried most presidential elections from 1968 to 2012 but, during the Reagan years in particular, shifted political discourse (and the tax code) in the United States profoundly to the right. Still, whoever looks closely at the era finds an undeniable excitement, a political, emotional, and moral energy coursing through public and private life, containing euphoric highs and unbearably painful lows. One individual who lived at the heart of the 1960s storms was the subject of my 2004 biography, William Sloane Coffin, Jr.: A Holy Impatience (Yale University Press).

Aside from Martin Luther King Jr., William Sloane Coffin Jr. was the most influential voice of liberal Protestantism in the latter half of the 20th century. He became a national figure in 1961 and held a spot on the national and international stage until his death in 2006 at 82. That national reputation was forged in his years as Yale University chaplain from 1958 to 1975.

Coffin was born in 1924 in New York City and raised as Presbyterian royalty at the pinnacle of metropolitan society. He was educated at Phillips Academy, Andover (1942), Yale (1949), and Yale Divinity School (1956). In May 1961, three years into his Yale chaplaincy, the 36-year-old minister garnered national headlines as the “Bus-Riding Chaplain” who led the first Freedom Ride that included Northern whites and African Americans. The Northerners were an all-Connecticut group: John Maguire, just beginning his career teaching religion at Wesleyan University, Maguire’s religion department chair David Swift, Yale Divinity School professor Gaylord Noyce, and an African American Yale Law School student, George Smith, later a longtime judge in New York City and state.

After a tense arrival in Montgomery, Alabama, Coffin spent an anxious night at the Rev. Ralph Abernathy’s house, ringed by National Guardsmen. Martin Luther King tried, unsuccessfully, to convince Attorney General Robert Kennedy to guarantee the riders’ safety if they pushed on the next day, and then led the group in prayer. The next morning, the group voted—by secret ballot—to continue the ride, but its members were arrested soon after reaching the bus terminal.

Coffin was on his way home after his release when LIFE magazine invited him to write about his experiences for its big spread on the Freedom Rides, later published as “Why Yale Chaplain Rode: Christians Can’t be Outsiders” (June 2, 1961). The article catapulted Coffin into the national consciousness. He suddenly became the most prominent Northern religious advocate for civil rights.

His national notoriety forced the cause of civil rights upon the relatively staid Yale community as never before. Older alumni called for his head; students and faculty debated his actions, while many contributed to his bail and legal defense; students packed Battell Chapel to hear him preach; speaking invitations poured into his office; and the Yale Daily News covered his speeches, sermons, and subsequent demonstrations and arrests.

His national notoriety forced the cause of civil rights upon the relatively staid Yale community as never before. Older alumni called for his head; students and faculty debated his actions, while many contributed to his bail and legal defense; students packed Battell Chapel to hear him preach; speaking invitations poured into his office; and the Yale Daily News covered his speeches, sermons, and subsequent demonstrations and arrests.

His hate mail also bore witness to the nerve he had touched. “Do you want your girl raped by a filthy, lousy Negro who would probably leave her with her throat cut?” asked one correspondent. Another, who claimed to be a Yale alum, wrote, “you have lowered yourself beneath the level of a ‘Nigger’ to disgrace the University which hired you to preach the Christian religion.”

As university chaplain, Coffin reported to Yale’s president. Lacking tenure, he kept his job for 17 more years by carefully cultivating his bosses, but also because both presidents he served under, the historian A. Whitney Griswold and the law professor Kingman Brewster, Jr., were personally committed to the chaplain’s right to act on his Christian convictions and to Yale’s character as an institution supporting freedom of expression.

While Coffin had demonstrated physical bravery and a certain tactical recklessness in undertaking the Freedom Ride, it posed no moral dilemma for him. He stood for liberal values and Christian courage, and mob violence directed at young people demanding equality—and refusing to fight back—was in his view simply un-American.

Opposition to the Vietnam War came more slowly, as it did for many, like Coffin, who had served in World War II. After he got out of the service, he went to Yale, graduating in 1949, and then served in the Central Intelligence Agency from 1950 to 1953. In the CIA he trained prospective spies to infiltrate the Soviet Union. From the CIA, he entered Yale Divinity School.

In the early 1960s, Coffin could not make up his mind about Vietnam. He kept his distance from the war’s opponents, some of whom struck him as naïve about Communism and needlessly anti-American. In spring 1965, however, Paul Jordan, a Yale music student (and later eminent musician), “accosted him with the audacity of youth”—as Jordan described it in my interview with him—and gave Coffin a “bulging manila folder,” as Coffin would later recall in his memoir, full of information about Vietnam and the war. Coffin read it, increasingly appalled, and came off the fence.

In the early 1960s, Coffin could not make up his mind about Vietnam. He kept his distance from the war’s opponents, some of whom struck him as naïve about Communism and needlessly anti-American. In spring 1965, however, Paul Jordan, a Yale music student (and later eminent musician), “accosted him with the audacity of youth”—as Jordan described it in my interview with him—and gave Coffin a “bulging manila folder,” as Coffin would later recall in his memoir, full of information about Vietnam and the war. Coffin read it, increasingly appalled, and came off the fence.

With the assistance of the legendary student organizer Allard Lowenstein, Coffin first put together a now-forgotten group called Americans for Reappraisal of Far Eastern Policy (ARFEP) to raise questions indirectly about Vietnam. With chapters on a couple of dozen college campuses, and a roster of some big academic and religious names, ARFEP held one well-regarded national teach-in in October 1965, then quickly died when Lowenstein decided to run for Congress in November.

By late November 1965, an ecumenical group of eminent and activist liberal clergy and academics had founded Clergy Concerned about Vietnam (CCAV) and invited Coffin to speak at a New York City conference that attracted 400 people and significant press coverage. Finally in his true element, among other clergy and religious people, Coffin organized a network of national chapters during Christmas break, traveled the country speaking and holding press conferences, and hoping with his colleagues that President Lyndon Johnson would extend the U.S.’s month-long bombing halt. When those hopes were dashed on January 30 with the resumption of bombing, Coffin and CCAV (later Clergy and Laity Concerned about Vietnam, or CALCAV, and finally just Clergy and Laity Concerned, or CALC), never again put faith in any administration.

Coffin remained endlessly inventive in his strategies to gain publicity for an antiwar message. In fall 1966 he hatched a plan he called Vietnam Relief to send medical supplies to the victims of war throughout Vietnam, in the Communist north as well as in the south. “All men have more in common than in conflict,” he declared. Even though a Canadian organization would deliver the cargo, such an effort needed a U.S. Treasury Department permit. The media jumped on the story, vilifying Coffin’s group as sending aid to “Reds,” while U.S. Representative Robert Giaimo (D-New Haven) and U.S. Senator Thomas Dodd (D-Connecticut) made hay by demanding to know why the treasury had granted the permit.

But Coffin and his colleagues in CALC found that no matter how hard they worked, grew their organization, hosted national conferences, and gave sermons, press conferences, and speeches, they could not budge administration policy on Vietnam. President Johnson had famously dug in his heels.

Along with an increasing number of antiwar activists, they decided to target the selective service system, more commonly known as the draft. CALC leadership, all men of post-draft age, decided to put themselves in legal jeopardy. They pledged to violate the section of draft law that punished anyone “who knowingly counsels, aids, or abets another to refuse or evade registration or service in the armed forces.”

By fall 1967, the effort coalesced around support for a statement originating with an anti-draft, antiwar group called The Resistance, “A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority.” In October Coffin traveled to Boston, where he collected draft cards at a packed service at the Arlington Street Church, and at the end of the month to Washington, where the antiwar movement had planned large demonstrations. At a press conference on the steps of the U.S. Department of Justice building, Coffin spoke, concluding, “Nor can we educate young men to be conscientious only to desert them in their hour of conscience. So we are resolved, as they are resolved, to speak out clearly and to pay up personally.” His group of 11 luminaries and draft resisters then met with Assistant Deputy Attorney General John McDonough, who refused to accept their briefcase full of draft cards. They left it anyway.

Coffin was delighted and proud that Yale was the single largest source of draft cards turned in that day to the justice department: 25 divinity school students, 16 other students, and 6 faculty members. That probably accounted for FBI agents’ showing up on campus a couple of days later and interrogating students. According to student George Stroup, it “soon became apparent that they had no interest in me whatever. They were after Bill [Coffin]. They wanted me to say that Bill had influence me or persuaded me to return my selective service card. . . . I refused.”

Yale University and its Chaplain’s Office became the center of student draft resistance in the northeastern U.S. Coffin influenced young men—and their families—across the country, often without knowing them. While researching my biography, I read hundreds of letters from young men, their fathers and mothers, their wives and girlfriends, all deeply concerned about the war, the draft, and the choices confronting them. Coffin answered all of these letters, often at some length. One hit particularly close to home as it involved a student at the University of Hartford, where I currently teach.

In November 1968, Coffin spoke at an antiwar rally on the New Haven Green and ended with St. Francis of Assisi’s prayer, “Lord make me an instrument of thy peace.” A young man—as he later related to me—stood and offered his draft card, saying, “My name is Gordon Coburn and I’m a sophomore at the University of Hartford and I’m doing this because I’m a Christian.” Three friends, and approximately a dozen others, joined him.

Coburn’s father Ralph, a Harvard-educated lawyer, veteran, and an admiral in the U.S. Naval Reserve, wrote a furious letter to Coffin insisting that “you must bear the major responsibility” for any consequences of Gordon’s “foolhardy act.” I reached Gordon by phone in fall 2000, and he immediately recalled the incident that had occurred 32 years earlier. “The whole experience changed my life,” he told me. “I hadn’t planned to turn my draft card in. None of us had. . . . Bill was inspiring. It seemed at the time I could do no other.” (A former seminarian, he was quoting Martin Luther here.) “I remember walking back to the car and the wind whistling through the trees and the tall buildings and feeling the entire weight of the U.S. government about to fall on me, and also knowing that I’d done the right thing. It was very powerful, and also very, very scary; all of a sudden I was on the other side.”

Coburn was never drafted, though he was reclassified 1-A (immediately eligible for the draft, as opposed to the 2-S student deferment he had had). He began building a file to apply for conscientious objector status, but then “flunked the physical” in his senior year. His decision to object “was a crossroad,” he explained, leading him to choose “a different route, a road dictated by conscience, by a sense of ministry.” Currently chair of the alcohol and drug counseling department at Santa Barbara City College, Coburn met Coffin in 1992 and thanked him for his speech that day nearly a quarter century earlier. Coffin, who was rarely known for his modesty, protested: “I didn’t do anything. I just spoke my conscience.” Coburn persisted: “You recited the prayer.” “Well, let’s give St. Francis credit then,” Coffin replied.

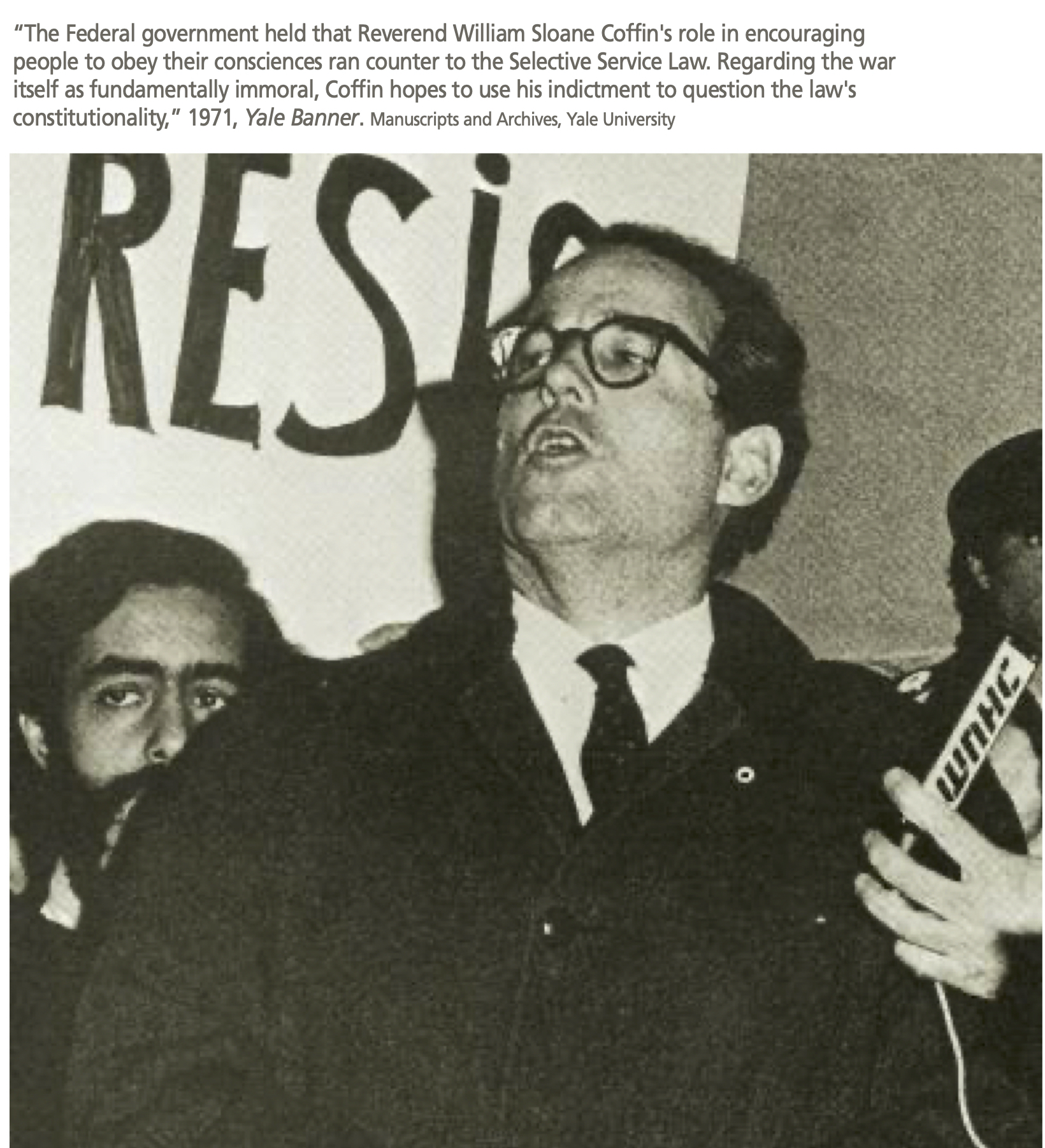

The federal government caught up with Coffin in January 1968. The justice department indicted him and four others— Dr. Benjamin Spock, Mitchell Goodman, Marcus Raskin, and Michael Ferber—with conspiracy to violate the selective service law. The irony of the conspiracy charge was that the defendants, quickly dubbed the Boston Five, met for the first time when they gathered together with their lawyers.

It was the first big trial of the antiwar movement. The government’s strategy completely backfired in the realm of public opinion. Spock was the most famous pediatrician in America, Coffin the best-known college chaplain, and all became bigger celebrities. Coffin recalled, “at universities, where before I had addressed hundreds, now there were thousands.” The immense press attention was frequently sympathetic; after all, Spock was an American institution, while Coffin’s elite credentials, his CIA service, and his extraordinary charm played extremely well against the demeanor of the judge, an 85-year-old authoritarian former prosecutor who clearly sided with the prosecution.

The Yale community stood behind Coffin, including, most importantly, President Brewster. The case cemented Coffin’s centrality in the peace movement, inspiring students, colleagues, and Americans across the country to discuss, argue, and express their opinions about the war and the draft. Coffin was convicted, but he successfully appealed. He could have been retried; instead, the government dropped the charges.

Coffin’s willingness to risk substantial jail time on behalf of antiwar activity drew support from unexpected sources all over the country. After his conviction, he heard from Louis “Bo” Polk (Yale 1954), a General Mills vice president, who offered to contribute to his defense. “I just want to tell you how much I deeply admire your willingness to search deep within yourself as to what you really believe in and then commit yourself to a course of action in terms of that belief. . . . I don’t feel I would have gone as far as you have gone, but by God we need Bill Coffins in this world.”

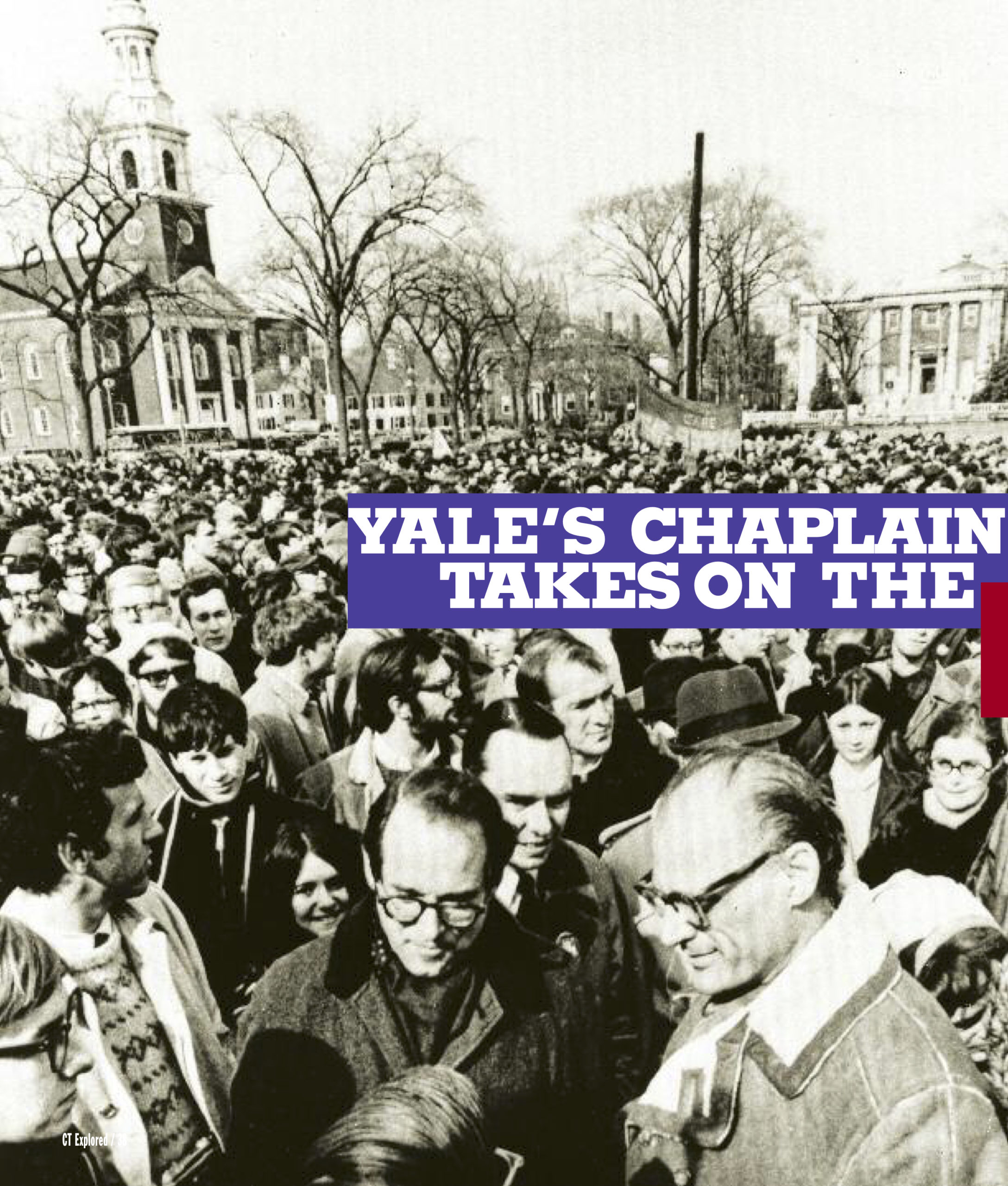

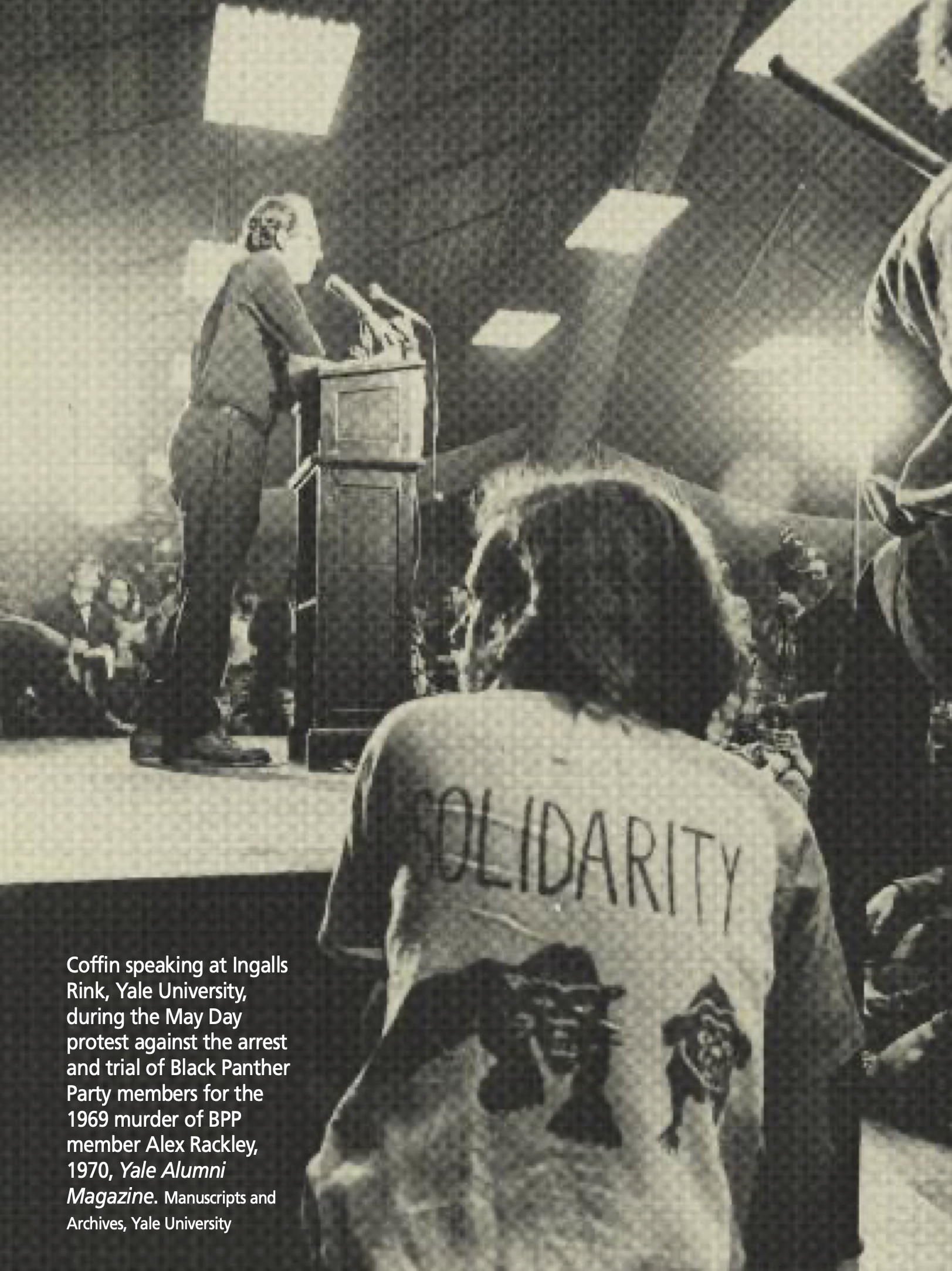

Coffin remained a powerful voice within the movement and continued to have immense stature at Yale, where he played a critical calming role during the events around the New Haven Black Panther trial, known collectively as May Day 1970. But as the war ended, and Coffin lost his principal antagonist for the previous decade, he also lost focus and drive. He decided to leave Yale and his miserable second marriage at the same time, at the end of 1975, drifted for a couple of years, living with family and friends, and published his memoir Once to Every Man (Atheneum) in 1977. Late that year he became senior minister at Riverside Church in New York City, the flagship, if somewhat staid, church of American mainline Protestantism. He transformed that pulpit too in the next decade, making it into a national and international center for peace and social justice ministry. Though he was born in New York City and died in Strafford, Vermont, it was during his years in Connecticut that he made himself into one of the most eloquent, passionate, and influential ministers in the country.

Warren Goldstein is professor of history and chair of the history department at the University of Hartford, where he also serves as the university’s Distinguished Teaching Humanist. He is the author, among other books, of William Sloane Coffin, Jr.: A Holy Impatience (Yale, 2004).