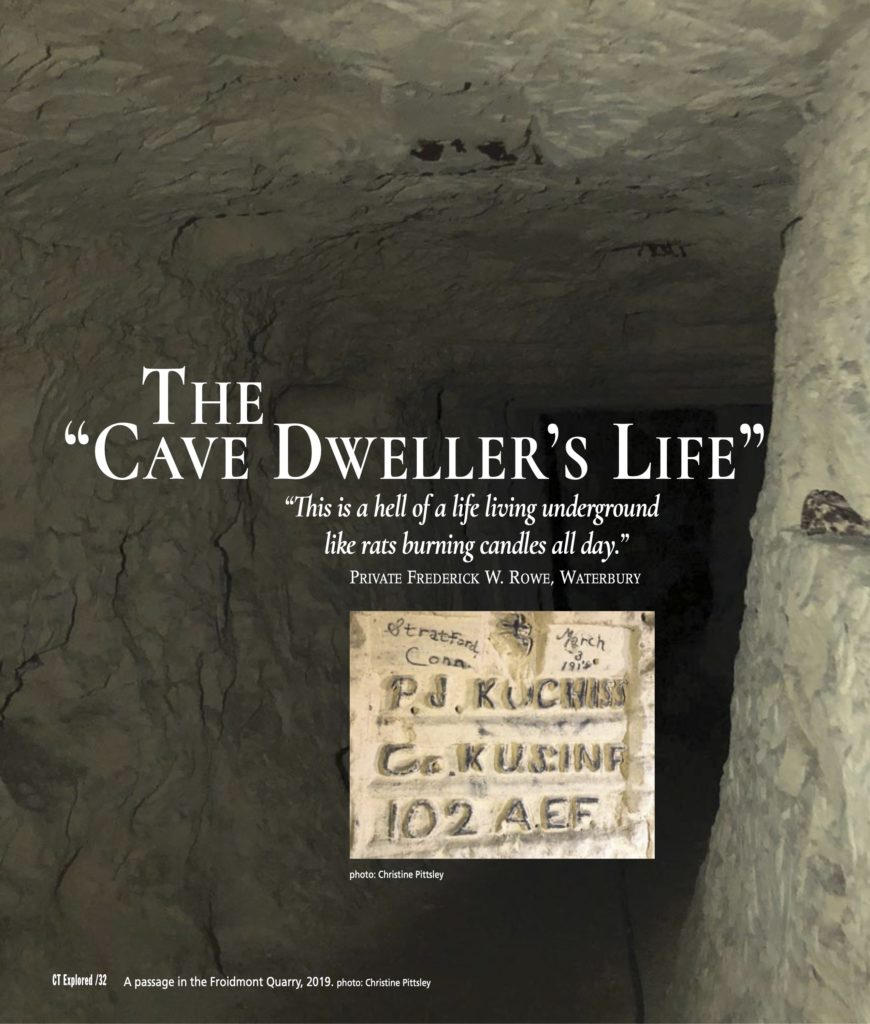

A passage in the Froidmont Quarry, 2019. photo: Christine Pittsley; (inset) photo: Christine Pittsley

by Christine Pittsley

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2020-2021

“This is a hell of a life living underground like rats burning candles all day.”

Private Frederick W. Rowe, Waterbury

A few hours northeast of Paris, in the Picardy region, is the Chemin des Dames, or Road of the Ladies. This 30-kilometer road runs along an east-west ridge between two valleys and, during World War I, was captured by the Germans in September 1914. Fighting was heavy here, and the French retook the sector three years later, in October 1917, before losing it again in May 1918. During this brief window, members of the 26th “Yankee” Division, made up of U.S. National Guard troops from around New England, became the only American soldiers to occupy the sector. And their accommodations were unlike any they had lived in before.

In newspapers, letters, and diaries in the Connecticut State Archives, Connecticut soldiers described what life was like on the Western Front. In a letter to his mother printed in the April 7, 1918 Hartford Courant, Private Max Haley of Bloomfield wrote:

We passed through villages completely in ruins, and I mean by this not a house left standing, trees blown to pieces, roads demolished, only a home for rats. As buildings are things of the past up in this war region, we were compelled to get acquainted with the Cave Dweller’s life.

Captain Albert H. Griswold of New Britain found an ingenious way to depict his surroundings to people at home while getting past the censors. In a letter to New Britain Mayor G.A. Quigley, printed in the New Britain Herald, March 23, 1918, he wrote:

Go down into the darkest corner of your cellar take a fine mahogany parlor table with two or three candles to see by, stick these on the table with their own grease, then take a cracker box to sit on. Just imagine yourself about 35 or 40 feet underground and you will come pretty near to imagining the conditions under which I am writing. If you want to make it a little more realistic just set a trap the night before and catch three or four fat rats and set them under the table.

Connecticut soldiers with a French citizen at the entrance to Froidmont Quarry, c. February or March 1918, France. photo: Corporal Merritt E. Learned

Connecticut’s 102nd Infantry Regiment learned about the realities of war along this ridge. They experienced their first gas attacks, heard the nonstop artillery barrages, and watched the daily aerial battles, forcing them to turn to the earth below them for shelter. Dugouts were carved into the sides of hills and quarries cut deep underground in the chalk-and-limestone bedrock. Private William J. Scanlon of Newington saw distinct advantages in their subterranean barracks. Writing to his parents on March 3, 1918,

From what we can learn from the Frenchmen, [the caves] were quarries, but not like ours at home. They are more like our mines. When you fit them up with electric lights and bunks arranged like those on a ship they make great quarters. The best thing about them is they are absolutely shell-proof, being a good many feet underground.

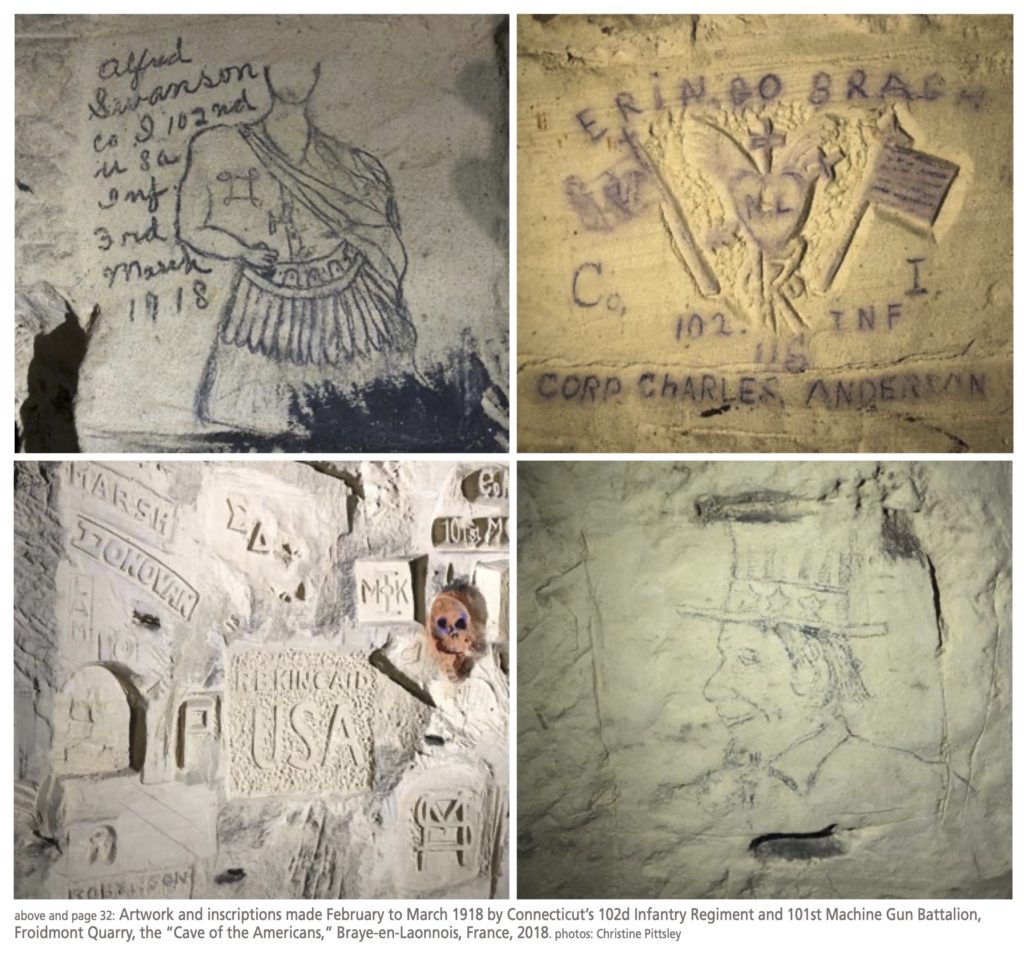

The soft chalk and limestone proved an excellent canvas for recording soldiers’ thoughts and experiences. One of the largest quarries was at Froidmont. It is known today as “Creüte des Américains” or “Cave of the Americans” for the New Englanders who left hundreds of inscriptions and graffiti behind on the walls. Soldiers drew images in pencil of Uncle Sam, carved their names into the walls, and used the smoke from their candles to write their names on the ceilings. For many soldiers this was one of the last marks they would leave on the world.

Froidmont encompassed nearly 100 acres of rooms and tunnels more than 30 feet below ground. “It was just like a large underground city, and would hold probably 10,000 men; … In this cave was our main dressing station, eating quarters for the men and a canteen where you could purchase food, chocolate, wine etc.,” wrote Lieutenant William P.S. Keating of Willimantic to friends in Hartford in April 1918. Chapels, like the one at Rouge Maison quarry, were hewn into the stone to meet the spiritual needs of soldiers.

Artwork and inscriptions made February to March 1918 by members of Connecticut’s 102nd Infantry Regiment and 101st Machine Gun Battalion on the walls of the Froidmont Quarry, Braye-en-Laonnois, France, 2018. photos: Christine Pittsley

A few quarries are still accessible and, under the care of vigilant guardians, have become protected historic monuments. Some are lost to time, have been looted, or are too dangerous to visit. Exploring these places today you begin to understand the world that those Connecticut doughboys inhabited and why they felt the need to let someone know they were there.

Christine Pittsley was project director for the Connecticut State Library’s award-winning World War One centennial programs. “Digging Into History” brought 15 Connecticut high school students to France in 2019 to restore a section of WWI trenches once occupied by Connecticut troops. She last wrote, “Remembering World War I,” Spring 2017.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut in World War I in Spring 2017, Winter 2014/2015, and on our Connecticut at War TOPICS page.

GO TO NEXT STORY