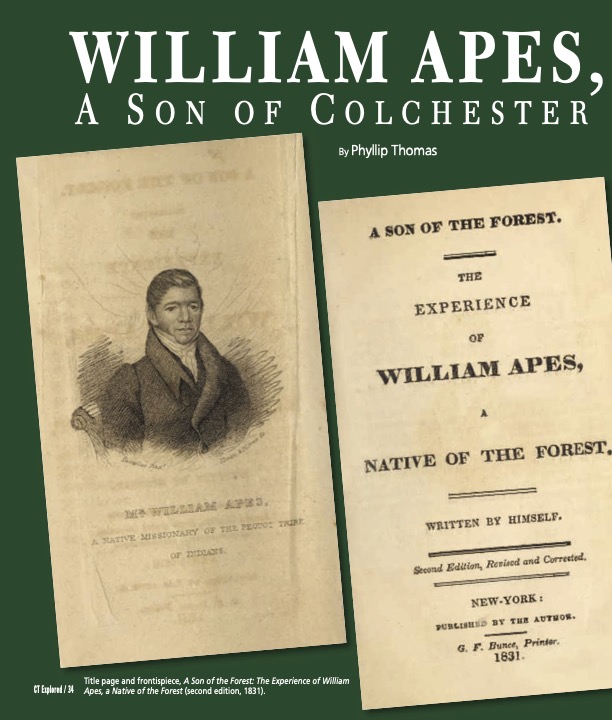

Title page and frontispiece, A Son of the Forest: The Experience of William Apes, a Native of the Forest (second edition, 1831).

By Phyllip Thomas

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2021-2022

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

My reading selection is from A Son of the Forest. The Experience of William Apes, A Native of the Forest. Comprising a Notice of the Pequod Tribe of Indians. Written By Himself (1829).

Three things to know about Apes: he is the first-ever published Pequot, he is a public example of forced cultural assimilation, and one of his descendants is a court officer in The Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Court system today. Apes was born in 1798 in Colrain, Massachusetts, and as an adult became an itinerant Methodist minister and activist for Native American rights.

…I was born—January 31st, 1798. Our next remove was to Colchester, Conn., near the sea board; …[We] then lived with my grand-father and his family, in which dwelt my uncle. … My father and mother made baskets which they would sell to the whites, or exchange for those articles only, which were absolutely necessary to keep soul and body in a state of unity. Our fare was of the poorest kind, and even of this we had not enough, and our clothing also was of the poorest description, literally speaking we were clothed with rags, so far as rags would suffice to cover our nakedness. We were always happy to get a cold potatoe for our dinner, and many a night have we gone supperless, to rest, if stretching our wearied limbs on a bundle of straw without any covering against the weather, may be called rest. We were in a most distressing situation. Too young to obtain subsistence for ourselves by the labor of our hands, and our wants disregarded by those who should have made exertions to supply them. Some of our white neighbors however taking pity on us, frequently brought us frozen milk, which my mother would make into porridge, and we would all lap it down like so many hungry dogs, and thought ourselves well off when the calls of hunger were thus satisfied. And we lived in this way suffering from cold and hunger for some time.

… My father and mother fell out, that is, they quarrelled, parted, went off a great distance, leaving us with grandfather and [grand]mother to shift for ourselves. …My grandmother went out one day; she got too much rum from the whites, and on returning she not only began to scold me, but to beat me shamefully with a club (the reason of her doing so I never could tell.) … and so she continued until she had broken my arm in three places. I was only four years of age, and of course could not take care of myself. But my uncle, who lived in the other part of the house, came down to take me away, when my grandfather made towards him with a fire-brand; but he succeeded in rescuing me, and thus saved my life, for had he not come at the time he did to my relief, I would certainly have been killed. …My uncle took and hid me away from them, and secreted me until the next day. When they found me, and discovered how dangerously I had been injured, they were compelled to have recourse to the whites.

My uncle went to the person who had often sent us milk, and as soon as he learned what had happened, he came straight off to see me and when he reached the place he found a poor little indian boy, all bruised and mangled to pieces. He was anxious that something should be done for us, and especially for me. He therefore applied in our behalf to the selectmen of the town, who after considering the application, adjudged that we should be taken and bound out. As for my part, I was a town charge for about a year, as the wounds inflicted by my grandmother entirely disabled me for that length of time. … The surgeon was sent for, who called in another doctor, and down they came to Mr. Furman’s house, where the selectmen had ordered me to be carried.

Now this dear man and family were sad on my account. Mrs. Furman was a tender-hearted lady, and nursed me, and had it not been that they took the best possible care of me, I think I should have died. … If I remember right, it was four or five days before the doctor set my arm, which was consequently very sore. I was afterwards, told that during the painful operation I never murmured.

… I suppose that the reader will naturally say, ‘What savage creatures my grandparents were to treat unoffending or helpless children in this manner.’ But this treatment was the effect of some cause. I attribute it in part to the whites, because they introduced among my countrymen ardent spirits; seduced them into a love for it, and when under its baleful influence, wronged them out of their lawful possessions—that land where reposed the ashes of their sires—and not only so, but they committed violence of the most revolting and basest kind upon the persons of the female portion of the tribe, who until the arts, and vices, and debauchery of the whites were introduced among them, were as happy, and peaceable, and cheerful, as they roamed over their goodly possessions, as any people on whom the sun of heaven hath ever shone. The consequence was, that they were scattered abroad. Now, many of them were seen reeling about intoxicated with liquor, neglecting to provide for themselves or families, who before were assiduously engaged in supplying the necessities of those depending upon them.

After I had been nursed up about a year, I had so far recovered, that it was thought proper to bind me out, until I should attain the age of twenty-one years. As I was then only five years old, Mr. Furman thought he could not keep me, as he was a poor man, and obtained his living by the work of his hands. He was a cooper by trade, and employed himself in his business when he was not engaged in working on his farm. They had become very fond of me, and … as I loved them with the strength of filial love, he at last concluded to keep me until I was of age. According to the spirit of the indentures, if I mistake not, I was to have so much instruction as to be able to read and write, and at the expiration of the term of my apprenticeship they were to furnish me with two suits of clothes. … According to their agreement, when I had reached my sixth year, they sent me to school—this they continued to do for six successive winters, in which time I learned to read and write, so that I might be understood. This was all the instruction of the kind I ever received. But I desire to be truly thankful to God for this – I cannot make you sensible of the amount of benefit I have received from it.

My father introduced me to William Apes and there are many reasons to agree with him about this reading selection’s being a compelling narrative. Significant levels of empathy would be felt by almost any person who read this excerpt. A deeper level of understanding of Apes’s childhood will magnify and broaden emotional impacts upon the reader.

My most difficult task is choosing the thoughts to share with readers since each of the dominant topics deserve a book of their own from a Pequot perspective. One overarching topic is inter-generational trauma and its impacts—old and new—upon the Pequot families that make up our Tribe. The very nature of such trauma produces certain outcomes, one of which is the creation of self-imposed trauma over time by my own Pequot people. All original trauma-based impacts upon us therefore become magnified creating dual waves of generational impact upon the same core group of Pequot families.

Another overarching concept is that our entire Pequot world-view, spirituality, self-image, and personal fulfillment are all traditionally based upon a single thing: relationships. Relationships to our Creator, our ancestors, living relatives (not just people), to future generations, the Earth and skies, and the passage of time are among the things that ground us culturally. The greatest impacts upon traumatized Pequot people come from generations of shattered relationships and our reduced ability to nurture them. Children have often been a powerless piece of America society. The most fragile relatives could not and cannot defend themselves against the adults in charge of their lives.

The fact that Apes’s parents made baskets tells us that they knew the land and traditional cultivation methods as well as traditional crafts. This knowledge base tells us that their family relationships were intact: traditional learning requires contact among groups of our people. For his parents to have that cultural resilience, though, actually gave them lesser chances of earning money and feeding their children within a capitalist society. Selling baskets to a market not inclined to value and appreciate this work as highly as their own community was an alternative to having to assimilate to a colonial job for the same audience. Apes did not get as much of the benefit of such broad and deep Pequot family contact or the cultural knowledge and resilience that it creates.

Parents deserting children and grandparents (in this case, who are alcoholics) stuck with those responsibilities is a typical “home” child-abuse scenario. Apes was impacted deeply, as were many thousands of other Native children. The typical “away” child-abuse scenario for Tribal kids involved forced attendance at Indian boarding schools and the ongoing rampant abuse of Tribal people by state foster-care systems.

Shattered family bonds and extreme poverty contributed to hundreds of years of hidden indentured servitude for Pequot people and many others. My great-great-grandfather was a victim of such weak family bonds and poverty. His name was Clifford Sebastian Sr. and he was “farmed out” to farmers in Stonington, where he fought for his life while his Pequot relatives back at Mashantucket got most of his “earnings.” Please pay attention to how happy Apes was to be with the Furmans. When successive generations see all of their most precious resources raped and pillaged, they often become desperate and dangerous people. Perhaps my great-great-grandfather was better off with the farmers in Stonington.

Phyllip Thomas is Youth Council Chairman, Mashantucket Pequot Tribal Nation. He is pursuing a Masters Degree in American Indian Studies with a focus in Tribal Governance and Leadership.

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO WINTER 2021-2022 CONTENTS