(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2019

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

From the moment European colonists set foot on New England’s stony shores, they reshaped its ecosystems. Forests were consumed for firewood, wolves and cougars succumbed to bounty hunters, and mazes of dirt roads fragmented the land. One of the most profound transformations, however, was also among the subtlest: the destruction of Castor canadensis, the North American beaver.

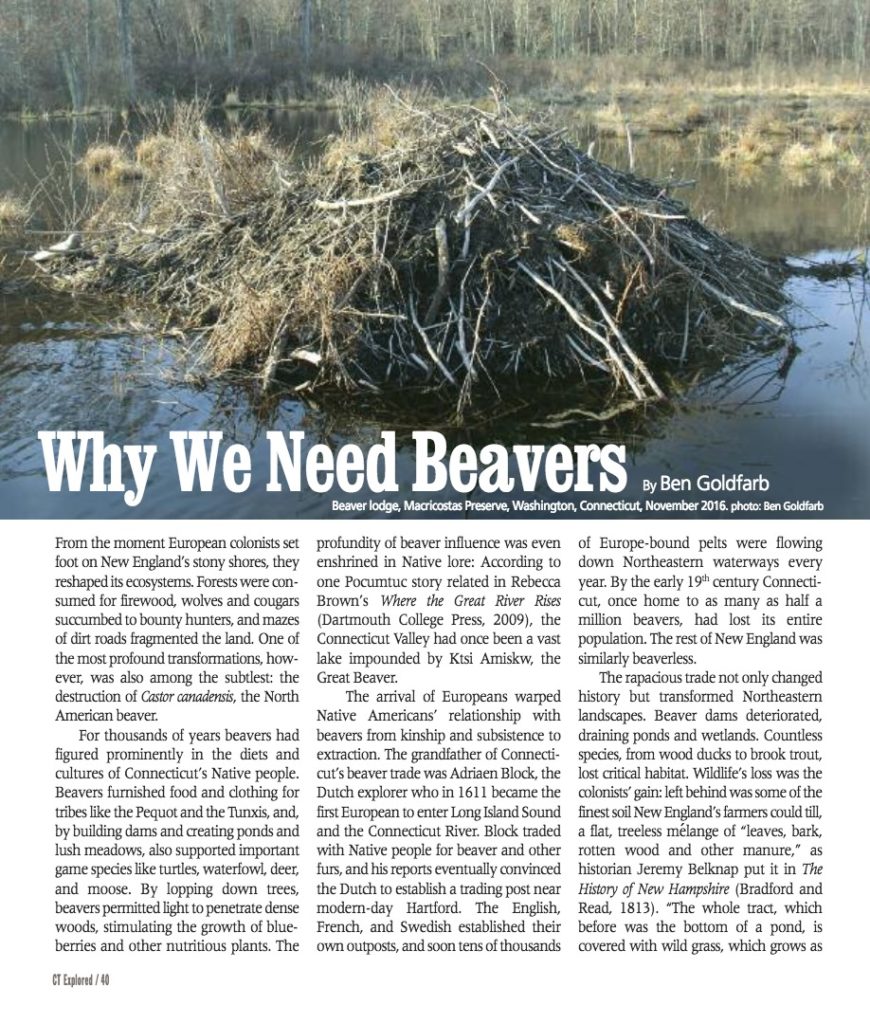

For thousands of years, beavers had figured prominently in the diets and cultures of Connecticut’s Native people. Beavers furnished food and clothing for tribes like the Pequot and the Tunxis, and, by building dams and creating ponds and lush meadows, also supported important game species like turtles, waterfowl, deer, and moose. By lopping down trees, beavers permitted light to penetrate dense woods, stimulating the growth of blueberries and other nutritious plants. The profundity of beaver influence was even enshrined in Native lore: According to one Pocumtuc story related in Rebecca Brown’s Where the Great River Rises (Dartmouth College Press, 2009), the Connecticut Valley had once been a vast lake impounded by Ktsi Amiskw, the Great Beaver.

The arrival of Europeans warped Native Americans’ relationship with beavers from kinship and subsistence to extraction. The grandfather of Connecticut’s beaver trade was Adriaen Block, the Dutch explorer who in 1611 became the first European to enter Long Island Sound and the Connecticut River. Block traded with Native people for beaver and other furs, and his reports eventually convinced the Dutch to establish a trading post near modern-day Hartford. The English, French, and Swedish established their own outposts, and soon tens of thousands of Europe-bound pelts were flowing down Northeastern waterways every year. By the early 19th century Connecticut, once home to as many as half a million beavers, had lost its entire population. The rest of New England was similarly beaverless.

The rapacious trade not only changed history but transformed Northeastern landscapes. Beaver dams deteriorated, draining ponds and wetlands. Countless species, from wood ducks to brook trout, lost critical habitat. Wildlife’s loss was the colonists’ gain: left behind was some of the finest soil New England’s farmers could till, a flat, treeless mélange of “leaves, bark, rotten wood and other manure,” as historian Jeremy Belknap put it in The History of New Hampshire (Bradford and Read, 1813). “The whole tract, which before was the bottom of a pond, is covered with wild grass, which grows as high as a man’s shoulders… Without these natural meadows, many settlements could not possibly have been made.”

The rapacious trade not only changed history but transformed Northeastern landscapes. Beaver dams deteriorated, draining ponds and wetlands. Countless species, from wood ducks to brook trout, lost critical habitat. Wildlife’s loss was the colonists’ gain: left behind was some of the finest soil New England’s farmers could till, a flat, treeless mélange of “leaves, bark, rotten wood and other manure,” as historian Jeremy Belknap put it in The History of New Hampshire (Bradford and Read, 1813). “The whole tract, which before was the bottom of a pond, is covered with wild grass, which grows as high as a man’s shoulders… Without these natural meadows, many settlements could not possibly have been made.”

To understand how dramatically landscapes unraveled in beavers’ absence, consider the research of Johan Varekamp and Ellen Thomas. Varekamp is a geochemist at Wesleyan University; his wife, Ellen Thomas, is a micropaleontologist at nearby Yale. In the 1990s they organized a series of research cruises in Long Island Sound, using a bottom-penetrating tube to haul up cylindrical seafloor cores—columns of sediment layers deposited over centuries that reveal New England’s geological history.

When Varekamp and Thomas analyzed their samples, they found that diatoms, a silica-based algae, had exploded around 1800. That made sense: expanding colonies and their livestock had fouled the sound’s waterways with runoff, fertilizing the ocean with waste and birthing algal blooms. To their surprise, however, they also found an earlier spike in algae, in the late 1600s. Scouring history for an explanation, Varekamp thought about beavers. As the rodents vanished, he theorized, the same epic collapse of unmaintained dams that created peerless farmland also conveyed nutrient-rich pond sludge to the sea—a surge of fertilizer that he and Thomas termed the “beaver peak.” In other words, beavers were once so omnipresent in the Northeast that their extermination is still written in the seafloor itself.

Fortunately, Connecticut later regained its furry architects. Biologists released two beavers in Union in 1914, whose descendants gradually repopulated northern Connecticut. In the 1950s the state Board of Fisheries and Game (as it was then known) initiated a trap-and-relocate program that spread beavers throughout the rest of the state. By 2000 as many as 8,000 inhabited Connecticut, enhancing wetlands for water-dependent creatures from mergansers to mink.

Fortunately, Connecticut later regained its furry architects. Biologists released two beavers in Union in 1914, whose descendants gradually repopulated northern Connecticut. In the 1950s the state Board of Fisheries and Game (as it was then known) initiated a trap-and-relocate program that spread beavers throughout the rest of the state. By 2000 as many as 8,000 inhabited Connecticut, enhancing wetlands for water-dependent creatures from mergansers to mink.

Humans, too, benefit from beavers’ return. Just as beaver trapping once led to a slug of nutrients gushing into Long Island Sound, today their ponds act as landscape-scale kidneys, filtering out pollutants produced by farms and lawns. One 2015 study estimated that microbes found in beaver ponds are capable of breaking down nearly half the nitrates from southern New England’s rural watersheds, protecting the region’s estuaries from harmful runoff. Although beavers are still considered property-flooding, tree-felling pests in many quarters, permitting their continued return to Connecticut’s waterways could help us tackle some of our most pressing environmental problems.

Ben Goldfarb is an environmental journalist and a graduate of the Yale School of Forestry and Environmental Studies. This article is adapted from his first book, Eager: The Surprising, Secret Life of Beavers and Why They Matter (Chelsea Green Publishing, 2018).

Explore!

For more about beavers in Connecticut, see Beavers in Connecticut: Their Natural History and Management (Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, 2001) at

https://portal.ct.gov/-/media/DEEP/wildlife/pdf_files/habitat/beaverctpdf.pdf

“Fish, Game & Forest Conservation Through Time,” Spring 2021

Kids’ Page: “Hats Off to Birds and Beavers,” Spring 2021

Read all of our stories about landscape/environment on our TOPICS page.