(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Summer 2018

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

This story is adapted from Goldstein’s “Walter Camp and the Bureaucratization of the Strenuous Life,” in A Brief History of Sports (with Elliot J. Gorn, University of Illinois Press, 1993).

Celebrated for more than a century as “the father of American football,” Connecticut’s own Walter Camp was the most important sports figure in Connecticut’s history and was more responsible than anyone else for the institutional success of college football. During his nearly 50 years of service to the game, Camp revolutionized its rules and scoring, led his beloved Yale to still-unmatched records, invented and promoted the All-America teams (with sportswriter Casper Whitney), and became the game’s grand old man. He earned his historical honors: his name on the Walter Camp Memorial Gate leading to the Yale Bowl, his name on a postage stamp, and his name on a foundation that gives the annual Walter Camp Award to the college football player of the year.

As he nurtured the game, however, Camp shrewdly maneuvered to protect football’s corrupt and brutal side from public condemnation through the invention of noble, sentimental, and patently ridiculous myths of gentlemanly sportsmanship—even as he was complicit in establishing and promoting some of the worst aspects of the game. When we commemorate Camp as the “father of American football,” we also need to probe behind and underneath Camp’s treacly public posturing to acknowledge the full measure of his paternity.

In these early days there were only a handful of African-American college players, mainly because white colleges and universities admitted very few black students. Camp did not recruit any black players to the squads he coached in nearly 50 years, during which time some of his opponents, such as Harvard, did have the rare African-American player. He and Whitney did name Harvard’s center William H. Lewis to the All-America Team in 1892 and 1893 (the first black player so honored) and as the center on his All-Time All-America Team in 1900. Yale didn’t have a black player until Levi Jackson, who also served as team captain in the 1949 season.

The Early Game

Football was initially a college game. In the 1870s and 1880s college football teams, like other student activities, were run by students, who selected, coached, trained, organized, and financed the squads. Football quickly became the centerpiece of the new “extra-curriculum,” the array of activities including clubs, fraternities, debating and literary societies, and athletic teams designed to supplement the admittedly dreary curriculum of mid-19th-century college life. A student captain, often the school’s most gifted athlete, trained and disciplined his men, while other undergraduates held fund drives and raised subscriptions to support the team. As football grew in popularity, and brutality increased unchecked by the rules of the game, however, faculty and administration committees began in the 1880s to intervene in the organization and oversight of the game, while leaving direction of on-field play in student hands.

A student captain, often the school’s most gifted athlete, trained and disciplined his men, while other undergraduates held fund drives and raised subscriptions to support the team. As football grew in popularity, and brutality increased unchecked by the rules of the game, however, faculty and administration committees began in the 1880s to intervene in the organization and oversight of the game, while leaving direction of on-field play in student hands.

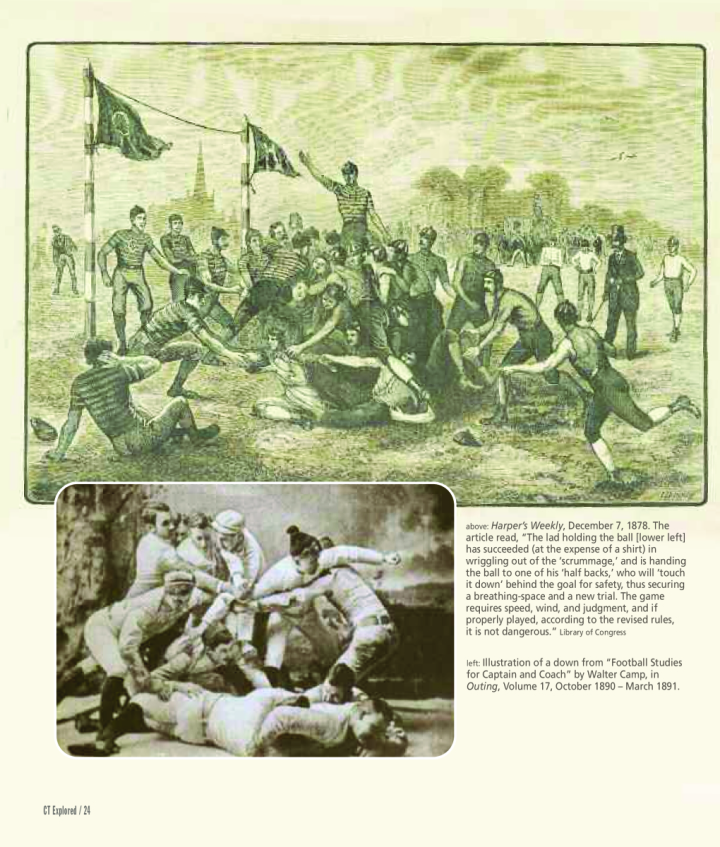

Before 1880 football resembled English rugby. Play was more or less continuous unless the ball went out of bounds, and almost any physical means of stopping the ball carrier was not only permitted but encouraged. There was no line of scrimmage, no series of downs, and no forward passing. Touchdowns were scored only by running.

The game became exceptionally popular, especially among the middle and upper classes, first in the Northeast and then across the country. The annual Thanksgiving Day championship played in New York City between the two best college teams, usually Yale and Princeton, kicked off the winter social season and by the early 1890s drew as many as 40,000 spectators. Wealthy patrons paid up to $150 (more than $3,500 in today’s dollars) for boxes with several seats, drove up Fifth Avenue in elegant liveries in their jewels and finery, and wagered the equivalent of millions on the game’s outcome.

Still, the game provoked enormous controversy throughout the late 19th century, on and off campuses. Some schools fought about whether to field a team each year. Readers will recognize the terms of the debate: then, as today, fundamental patterns and tensions persisted over time and erupted occasionally into full-blown conflicts.

First, the game was extremely violent, routinely causing series injuries and at least a handful of player deaths each year. In the early 1880s, well before helmets were introduced, rules allowed players to hit their opponents with closed fists three times.

Second, many schools, including the most prestigious, adopted a win-at-any-cost attitude that commentators and especially college faculties found troubling. Dishonest recruiting practices verged on the laughable, as prized players “matriculated” at a number of schools during the same season, sometimes “transferring” from week to week! The 1932 Marx Brothers romp Horsefeathers, set in 1890, in which college president Groucho mistakenly hires Harpo and Chico (instead of a couple of local ringers) to play in his “big game,” only slightly exaggerates well-known real-life football shenanigans.

Finally, the sheer hoopla surrounding intercollegiate football led educational traditionalists to lament the transformation of their campuses into sites centered on social life and extracurricular activities, where students spent as little effort as possible on their studies. As Williams College alum Sanborn Gove Tenney wrote in Outing in 1890, “You do not remember whether Thorpwright was valedictorian or not, but you can never forget that glorious run of his in the football game of 18—, when, with his adversaries left behind, he made the touchdown that gave your college the championship and added another silk flag to the trophy room.” That was the world that Walter Camp first entered as a Yale undergraduate in 1875 and then helped to nurture into full flower.

Walter Camp Enters the Game

Camp joined the football team in 1876, just seven years after the first intercollegiate game was played in 1869 between Rutgers and Princeton. He served as captain his junior and senior years and played for two more years as a medical student after graduating in 1880. In addition to starring at football, he crewed, ran track, played tennis and baseball, and while in medical school coached both the football and baseball teams.

As a combination player, strategist, tactician, and innovator, Camp was unique. He first represented Yale at the second annual inter-collegiate rules convention in 1877 in which players from a handful of colleges met to try to agree on a common set of rules. The game began evolving away from rugby and toward a new, distinctly American game. In 1880 Camp offered one of the most far-reaching rules changes in the history of the sport: establishing the line of scrimmage. Two years later he proposed the series of downs to gain a set number of yards (initially five), new styles of blocking, tackles below the waist, and the modern scoring system.

Camp left medical school in 1882 and went to work for the New Haven Clock Company, first in sales in New York City. In 1888 he returned to New Haven, where he began a steady climb to the top of the company, serving as president and treasurer from 1903 to 1923 and chairman until he died in 1925.

He married Alice Graham Sumner, sister of Yale’s famous social Darwinist William Graham Sumner, in 1888, and for the next two decades they ran Yale football together. Alice attended practices, taking careful notes. Each evening the student coaches would huddle with the Camps to analyze the team’s work, and Walter would dispense advice and directions.

Camp was the unofficial czar of Yale’s football powerhouse in the late 19th and early 20th centuries—all while working at New Haven Clock. From 1876 to 1909 Yale lost exactly 14 games, fewer than one every other year. Camp compiled an astonishing, never-equaled record. Eventually former players, rivals, and admirers across the country copied his methods of factory-like, even military, organization and training.

Camp’s Dark Side

But for all of his rock-ribbed Victorian moral pronouncements, such as those he professed in his 1893 Walter Camp’s Book of College Sports (The Century Company) —“Be each, pray God, a gentleman!” ran one refrain (lifted from a dreadful Thackeray poem)—Camp had a less known, and far darker, role. Even as he worked to establish many aspects of the game that fans continue to enjoy today, he became the father of the corrupt edifice of big-time college sports and fostered the brutality that has damaged the brains and lives of literally countless men over the past century and a quarter.

“A gentleman never competes for money, directly or indirectly,” he intoned in his book, all the while controlling a reputed $100,000 (about $2.5 million in today’s dollars) slush fund for athletic “tutoring.” Yale, like all other competitive football programs, shamelessly imported ringers for key games—ringers who then found themselves playing for different teams weeks or months later.

One of Camp’s team captains in 1904, Torrington’s James J. Hogan, an Irish immigrant, entered Yale at age 27 (directly from Andover, where he also played football), paid no tuition, and lived in a suite in Vanderbilt Hall, then understood to be Yale’s most luxurious dorm. With two teammates, Hogan held the scorecard franchise at Yale baseball games (meaning that he retained all proceeds from selling the scorecards) and enjoyed the exclusive campus cigarette franchise for the American Tobacco Company, earning a commission on every box of “Egyptian Deities” and “Turkish Moguls” sold at Yale’s famous watering hole, Mory’s—where they were known as “Hogan’s cigarettes.” But he did graduate, probably in 1905, and went on to Columbia Law School.

One of Camp’s team captains in 1904, Torrington’s James J. Hogan, an Irish immigrant, entered Yale at age 27 (directly from Andover, where he also played football), paid no tuition, and lived in a suite in Vanderbilt Hall, then understood to be Yale’s most luxurious dorm. With two teammates, Hogan held the scorecard franchise at Yale baseball games (meaning that he retained all proceeds from selling the scorecards) and enjoyed the exclusive campus cigarette franchise for the American Tobacco Company, earning a commission on every box of “Egyptian Deities” and “Turkish Moguls” sold at Yale’s famous watering hole, Mory’s—where they were known as “Hogan’s cigarettes.” But he did graduate, probably in 1905, and went on to Columbia Law School.

When Hogan died in 1910 at 37 from Bright’s disease, a Yale athlete eulogized him in a Yale alumni obituary: “His rugged honesty, unflinching morality, universal good nature, unselfish generosity, and manly demeanor made him one of the strongest and most lovable of Yale men.” Hogan may well have been good-natured, generous, and manly, but it took a massive exercise in denial to convince anyone of Hogan’s—or Camp’s—“rugged honesty and unflinching morality.” Despite its official image as a non-commercial, thoroughly amateur collegiate pursuit, the reality of the “game” has been otherwise from the get-go.

Camp’s biographers pay little attention to his acceptance of dangerous violence on the playing field. Recall the three-punch rule, for instance. Camp’s “reforms” led to yet more violent play. The low tackles he introduced reduced the effectiveness of open-field running with the football. The offense responded by developing “mass plays”—large numbers of players driving into the defense to gain the five yards.

In 1892 the introduction of the “flying wedge,” in which an entire offensive line smashed into just one defensive player, so appalled critics that Camp saw the need to defend his reputation. He joined a blue-ribbon commission “investigating” football brutality. The self-appointed commission of six men, including James Alexander, president of the University Club (of New York), Hartford’s Reverend Joseph Twichell representing Yale, and Robert Bacon representing Harvard, published their defense of the game in Football Facts and Figures (1894). As the commission’s key member, Camp decided which data to publish in the report. Not surprisingly, he asserted, “Harvard, Yale, and Princeton players during the previous 18 years had an ‘almost unanimous opinion’ that football has been a ‘marked benefit,’ both physically and mentally.” Of course, this did not address the key questions raised by critics. As the new secretary of the intercollegiate game’s rules committee, Camp outlawed the flying wedge and some other dangerous mass plays, and the game returned to its previous level of violence.

Football in Crisis

In 1905 the game faced its most serious crisis when 18 football players ranging in age from 13 to 27 died. Three died in college play, the majority in high-school play (including an 18-year-old Maryland girl), and one in a club game.

Even the sport’s most prestigious supporters knew they had to do something. Booster-in-chief (and Harvard graduate) President Theodore Roosevelt called head coaches and officials from the Big Three—Harvard, Yale, and Princeton—to the White House to “persuade them to play football honestly.” In response, Camp helped write the schools’ joint statement, reported in The Washington Post October 12, 1905, promising to “eliminate unnecessary roughness, holding, and foul play.”

In 1906 a reconstituted rules committee under Camp’s leadership—which became the NCAA—legalized the forward pass and doubled the yards to be gained on three downs to the current 10—representing a major shift designed to avoid major pileups of players. It was not enough. In 1909, four years after Roosevelt “saved football,” 26 players died, 10 in the college game.

The new organization called the Intercollegiate Athletic Association of the United States in 1910 became the National Collegiate Athletic Association (better known today as the NCAA). This history helps to explain the real purpose of the NCAA—to protect the reputation of collegiate athletics from those who think its games too brutal, too commercial, or too destructive of academic integrity. Whenever you read about the next “scandal” in top-flight collegiate sports, look back to the organization’s origins and you will understand why scandals are simply baked into the activity of the NCAA—which has always been most loyal to the colleges and universities hosting the games, not the well-being or academic success of the athletes themselves.

What is also usually missed in discussions of Camp is the way he built the modern successful college football team on the model of industrial and, to an extent, military organization. In fact, Camp ought to be well known as the man who brought bureaucracy to Roosevelt’s “strenuous life,” institutionalizing regular practice, training, and an athletic version of Frederick Winslow Taylor’s “scientific management.”

Owen Johnson, in his popular novel of 1890s Ivy League student life Stover at Yale(1912), captured this development perfectly. “What has become of the natural, spontaneous, joy of the contest?” one of his characters laments. “Instead you have the most perfectly organized business systems for achieving the required result—success. Football is riving slavish work.” Johnson likened Yale’s teams to the beef trust, which also had “every by-product organized, down to the last possibility.”

Camp himself liked to make the analogy to business.

Finding a weak spot through which a play can be made, feeling out the line with experimental attempts, concealing the real strength till everything is right for the big push, then letting drive where least expected, what is this—an outline of football or business tactics? Both of course.

The late-19th-century workplace saw complex manufacturing processes reorganized into a multitude of small repetitive tasks in the execution of which workers saw only a tiny piece of the whole. Employers increasingly arrogated to themselves the task of managing, measuring, organizing, and timing the production processes as a whole. This was precisely the pattern Camp employed in organizing Yale football. Generations of Yale men, trained in bureaucratic production on the gridiron, went on to leadership positions in American corporate life.

The late-19th-century workplace saw complex manufacturing processes reorganized into a multitude of small repetitive tasks in the execution of which workers saw only a tiny piece of the whole. Employers increasingly arrogated to themselves the task of managing, measuring, organizing, and timing the production processes as a whole. This was precisely the pattern Camp employed in organizing Yale football. Generations of Yale men, trained in bureaucratic production on the gridiron, went on to leadership positions in American corporate life.

Not only was Camp’s system the most effective, it was the most widely copied. After decades of being thrashed by Yale, Harvard hired coach Percy Haughton in 1908 to reorganize its slapdash football program. Haughton instituted a thoroughly military system of command and drills and lost only one game to Yale in eight years. Camp’s vision of the future—for better or worse—had triumphed.

Warren Goldstein, chair of the history department at the University of Hartford, is the author of Playing for Keeps: A History of Early Baseball (20thAnniversary Edition, Cornell University Press, 2009) and (with Elliott Gorn) A Brief History of American Sports(University of Illinois Press, 2013). He has written widely on the history of American sports.