By Sarah J. Morin

Court records are a treasure trove of information. People from all rungs of society have appeared in court throughout history, and a court case may be the only documented record of a person’s existence—especially if they were poor or marginalized. Recognizing the value of court records in enriching our understanding of history, the National Historical Publications & Records Commission (NHPRC) awarded the Connecticut State Library a grant in 2020 to preserve and enhance public access to the New Haven County Court records in the Connecticut State Archives. The majority of these records date from 1700 to 1855, with a few going back to 1666.

These records document a broad range of groups and socioeconomic levels, so one of our major goals is to identify and digitize all cases relating to African American, Black, and Indigenous persons, along with selected cases involving women, prominent people, and other research topics of interest. Our goal is to uncover the stories of traditionally marginalized groups so they are documented as fully and accurately as possible in the historical record. As of April 2023 we have preserved the New Haven County Court records from 1700 to 1810. In more than a century of cases, we discovered many that shed important light on the lives of women, African-descended, and Indigenous persons from the colonial era to the age of industry. While several of these court cases sadly confirm the marginalization of these groups—and the tantalizing details in the records often raise more questions about particular women, African-descended, and Indigenous persons than they answer—there are a few triumphs of justice and even subversions of popular historical myths.

Cases Involving African-descended, African American, and Black Persons

During the early 1700s African-descended persons were almost always subjects of cases, rather than plaintiffs or defendants. A frequent subject of the lawsuits between Euro-descended enslavers was the ownership of and liability for the illnesses or deaths of enslaved persons. In 1727 Joseph Rogers of Milford sued Isaac Gorham of New Haven for selling him a 9-year-old boy named Harry, whose consumption (the disease we now call tuberculosis) rendered him unfit for labor and therefore “wors[e]than nothing” in the eyes of his enslaver. In 1753 Samuell Bellomy of New Haven sued Samuell Talcott of Hartford for selling him a 14-year-old boy named Dick who could not work due to “[epileptic]fits, Intirely good for nothing.” Elnathan Taylor of New Haven sued Shadreuk Seegar of Wallingford in 1754 when Fortune, a 2-year-old boy Taylor had bought from Seegar, died six weeks after his purchase. And Abraham Dunyee and Abraham Shenk of Fishkill, New York sued Benjamin Richard of Waterbury in 1764 for selling them a 17-year-old girl named Hanah who could not work due to a “Confirmed Pox or Vener[e]al diseas[e].” While the record does not reveal where or how Hanah contracted this “pox,” the implications of her condition are disturbing. As Wendy Warren wrote in New England Bound: Slavery and Colonization in Early America (W. W. Norton, 2016), “for all the apparently consensual couplings made visible by those fornication cases, we might consider how many nonconsensual relations must have occurred, if New England’s version of chattel slavery was anything like that in the rest of the Atlantic world.”

Colonial Connecticut law rendered enslaved people property, or chattel, and listed them in estate inventories alongside household goods. New Haven County Court records document several instances in which sheriffs seized enslaved persons as collateral in debt cases. For example, in 1792 a girl named Susan and a boy named Sharper were taken as “property” in a lawsuit between Sheldon and William Clark of Derby. The court recorded no additional particulars about Susan or Sharper or explained why the constable chose to seize them instead of livestock or household goods. But this lack of information tells a story of its own. Court clerks only recorded details the judge or justice of the peace deemed important, which indicates that Susan and Sharper’s perceived financial value was the only detail they found relevant to this case. Because of this callous denigration of human life, all too often we can only glean small glimpses into the lives of those who were enslaved in 18th-century Connecticut. Yet it is still important to share these scant clues, as researchers may be able to someday connect Susan and Sharper to a larger story.

The population of free people in Connecticut grew after the American Revolution and the state’s adoption of a gradual emancipation policy in 1784, which decreed that all children of enslaved people who were born after March 1 of that year were to be freed when they reached age 25. In 1797 the age was reduced to 21. However, enslaved individuals born before 1784 were not automatically granted freedom, and the last enslaved persons in Connecticut weren’t fully freed until 1848, according to David Menschel’s article “Abolition Without Deliverance: The Law of Connecticut Slavery 1784-1848” in the Yale Law Journal 111, no. 1, October 2001. After 1784 African American and Black persons started appearing more often as plaintiffs and defendants in cases commonly involving debt, trespass, theft, and assault.

There were also several cases where freemen and freewomen fought against illegal enslavement and mistreatment during servitude contracts. In 1788 Philip of Cheshire (also identified as Philip Negro, Philip Negroe, and Philip Mollatto in the court records) sued Moses Blakesley of Cheshire for “caus[ing]him to work in confinement & servitude as his slave” after he entered the man’s service at age 10. In a satisfying turn of events, the court awarded Philip full damages of £500. Unfortunately, Philip was not so successful in his 1789 lawsuit against Samuel Merriam of Cheshire. Even after emancipation, Black and African American freepersons were often forced by economic circumstance to bind themselves in servitude under white masters. Philip worked as a servant for Merriam from February to April 1788 and objected to Merriam’s harsh treatment—Philip was “in every respect subject to him as tho[ugh]he had been Slave for life & the absolute property of the Def[endan]t.” The court adjudged Philip’s plea “insufficient,” since the contract had ended and he was ostensibly not subject to such treatment at present, and ordered him to pay Merriam’s court costs.

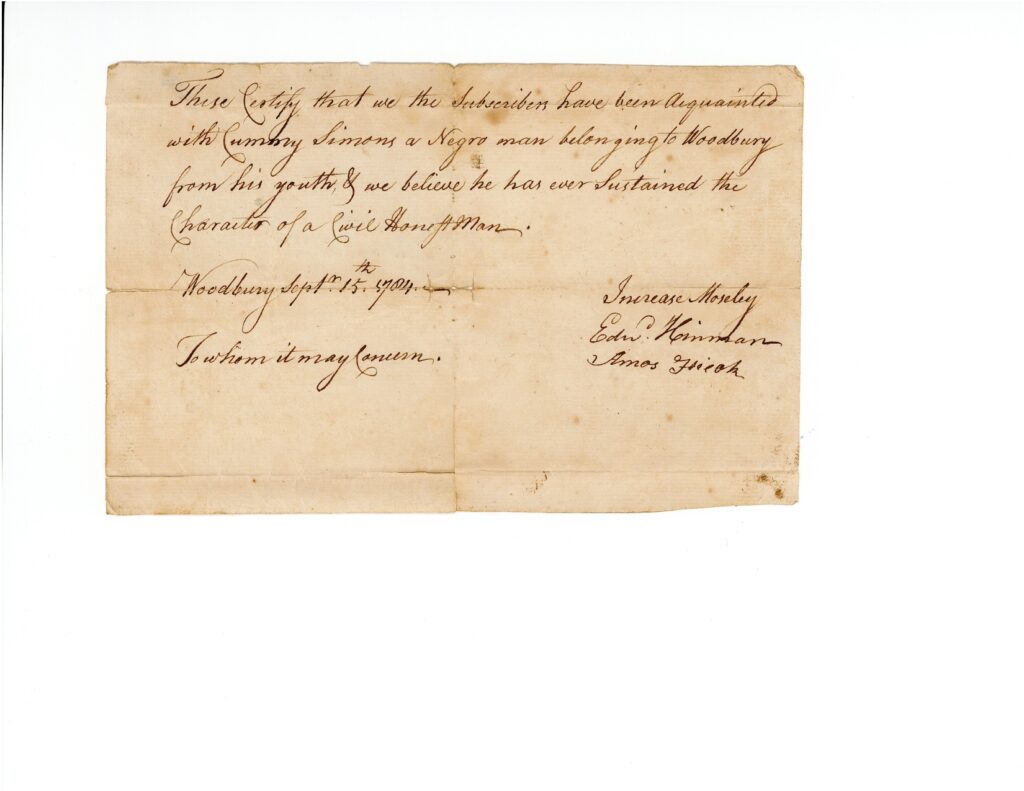

Another notable case was the 1784 debt lawsuit of Comme Simons vs. James Shop. The court sentenced Shop, a Black freeman of New Haven, to be bound in servitude to Simons, a Black freeman of Woodbury, for a period of four-and-a-half months in order to work off his debt. While it was not uncommon for debtors to be sentenced to a term of indenture to fulfill their debts, Simons vs. Shop is the only case we have discovered in the New Haven County Court records of a Black debtor’s being bound to a Black creditor.

Cases Involving Indigenous Persons

Indigenous individuals were identified in the court records as “Indian.” This designation makes pinpointing a particular tribe or nation difficult, as it could mean they were native to Connecticut, New England, the southeastern United States, or the West Indies. In addition to cases involving “Indian” persons, we are also scanning those with “Indian” place names in order to track inhabitancy and territories. These place names are often frustratingly vague, but many still provide important clues for researchers. In 1731, for instance, Joseph Tuttle of East Haven sued Peter Woodward of New Haven, claiming that Woodward “Demolish[ed]and Destroy[ed]three certain heaps of Stones Lawfully Landmarks Erected in three Several places which were part of ye bound or Land Marks of a tract of Land belonging to him s[ai]d Tuttle Lying at a place Called ye old indian field in East Haven.” In 1752 Edward Allen of Milford sued Peter and David Prudden of Milford for defaulting on a land purchase at “a place called the Indian Side in s[ai]d Milford.”

Character witness statement for Comme Simons v. James Shop, 1785. In this unusual case, Comme Simons (also spelled Cummy and Comma), a Black freeman of Woodbury, sued James Shop, a Black freeman of New Haven, for debt. In recompense, the court sentenced Shop to be bound in servitude to Simons for a period of four and a half months. Three (presumably English-descended) men acted as character witnesses for Simons.

Indigenous peoples were not enslaved as widely as Africans were, but individuals were often forced into servitude through debt or war. Indigenous slavery is poignantly demonstrated by the case of Nelle, a girl of Indigenous and African heritage whose enslavers went to court in 1745. Samuel Tyler of Wallingford sued Mathew McCure of Killingworth for fraud, alleging that because Nelle’s mother was an Indigenous freewoman from Long Island, Nelle was eligible to be freed at age 18. McCure had sold Nelle to Tyler with the promise that she was “A Negro, and Slave for life and that he had good right to sell her for life.”

Although the court found in favor of Tyler and awarded him the £160 he demanded in damages—which meant that Nelle was presumably eligible to be emancipated at 18—little information is given about the girl whose freedom was at stake. We cannot even pinpoint exactly how old she was because the court records described her as being “of about 8 or Nine Years of Age”—which raises the question of when she would legally be deemed 18. As in the majority of legal disputes we discovered regarding enslaved persons, Nelle was not a plaintiff or defendant, nor does she appear to have given testimony. While this case was purportedly about her, her voice is completely absent from the record. To compound this injustice, the favorable verdict Tyler received was by no means a guarantee of eventual freedom for Nelle, as McCure appealed to the New Haven County Superior Court.

Cases Involving Women

While enslaved persons were treated as chattel, women were treated as children. Under the legal principle of coverture, husbands were answerable for their wives, and fathers were answerable for their under-18, unmarried daughters. Only single women past the age of majority could represent themselves in court as “feme soles.” However, the stereotype of women as “virtuous ornament[s]… [of]gentility and leisured motherhood,” as Cornelia Hughes Dayton wrote in Women Before the Bar: Gender, Law, & Society in Connecticut, 1639-1789 (University of North Carolina Press, 1995), was a newer trope that didn’t gain popularity until later in the 18th century. Instead, women were expected to be capable and competent “helpmeets” of their husbands, representing their interests in business and court as well as the home.Indeed, women were often estate executors until the late 1700s, as demonstrated by the 1771 case of Anna Painter vs. Sarah Gorham in which two widows were embroiled in a debt lawsuit on behalf of their deceased husbands. Some women even served as their husband’s attorneys. For example, John Guy of Branford was a prolific debt plaintiff in the 1710s, and his wife Anna acted as his attorney in 5 of his 31 debt cases. As Laurel Thatcher Ulrich explains in her book Good Wives: Image and Reality in the Lives of Women in Northern New England, 1650-1750 (Vintage, 1991), the use of the word “attorney” in this specific circumstance did not suggest membership in the bar, as we use that word today, but that the woman was a “deputy husband” in court in her husband’s stead.

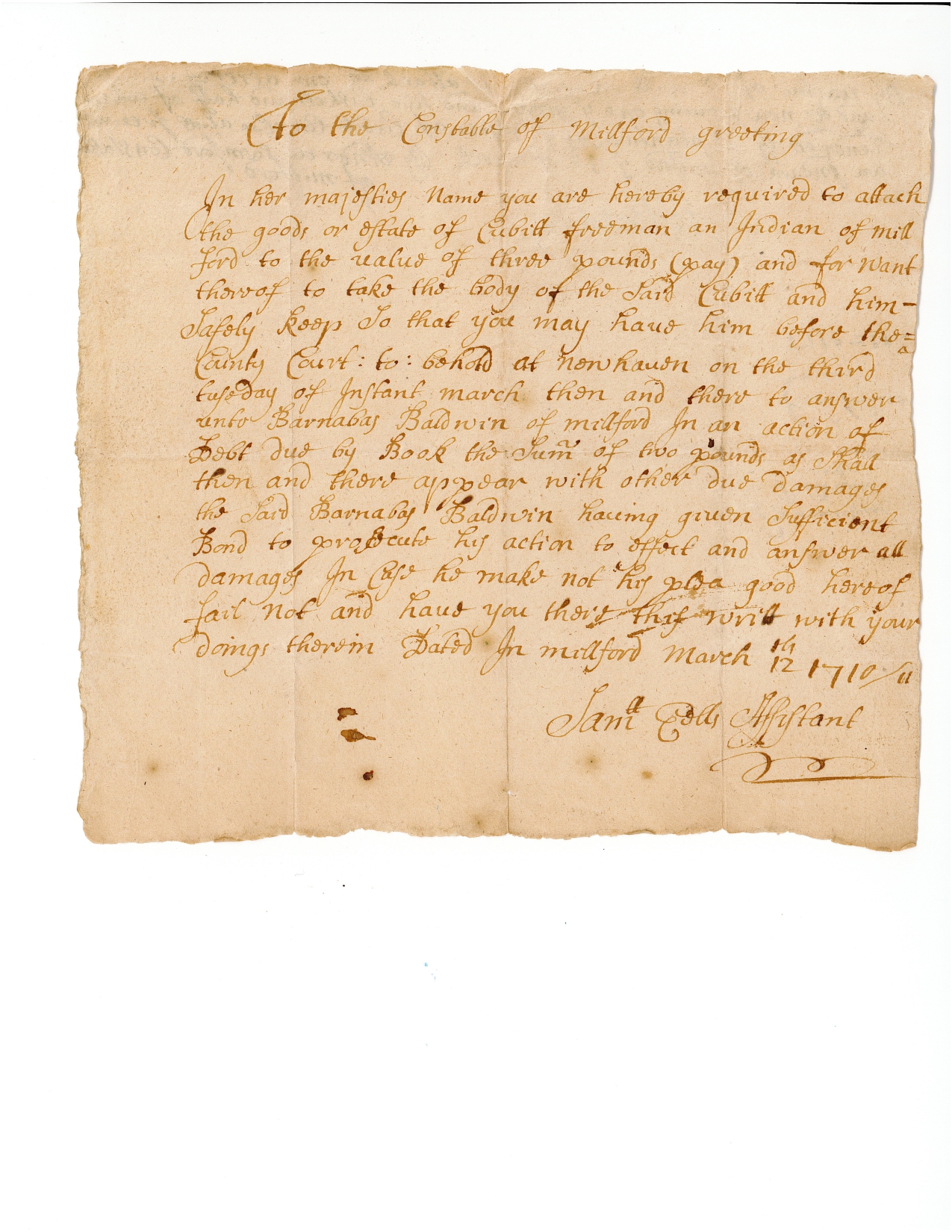

Writ for Barnabas Baldwin v. Cubitt Freeman, 1711. Baldwin sued Freeman, also known as Cubitt Carrbee or Cubit Carribe and described as “an Indian of Milford,” for debt. But Freeman failed to appear, “this Court being informed that he is out of this government” (County Court Records, New Haven County, Vol. 2, 1699-1712/13, p. 456).

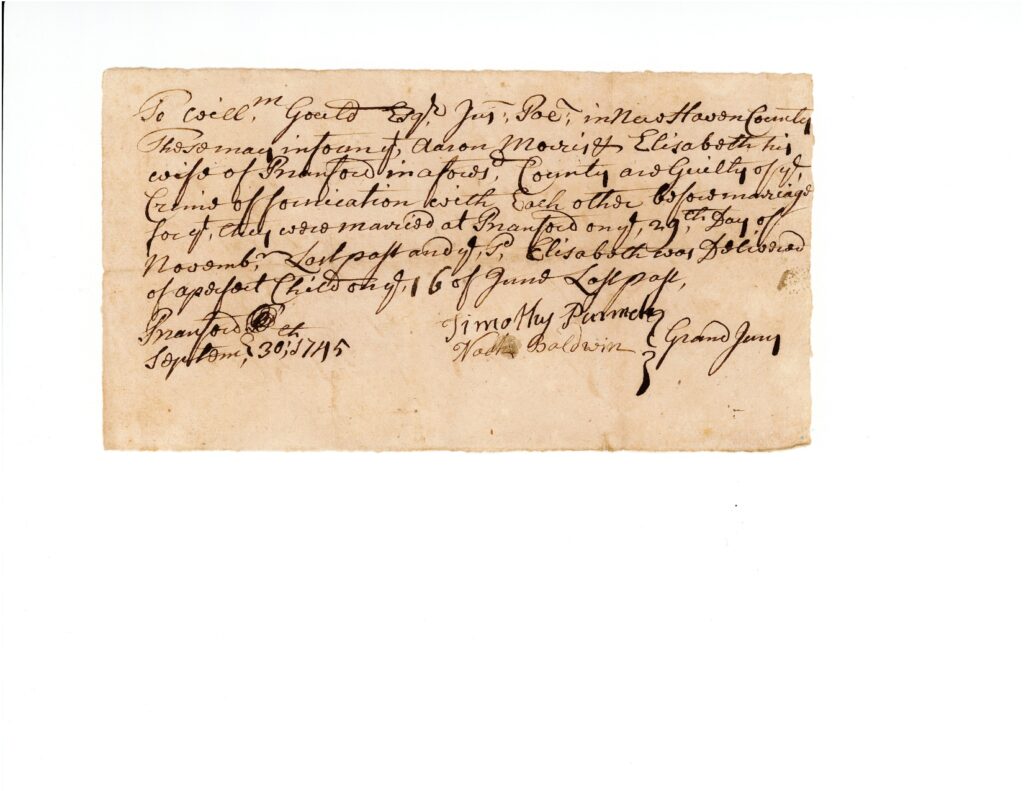

Verdict for Rex (the Crown) v. Aaron and Elisabeth Morris, 1745. The grand jury deemed the Morrises “guilty of ye crime of fornication with each other before marriage for yet they were married at Branford on ye 29th day of November last past and ye said Elisabeth was delivered of a perfect child on ye 16 of June last past”—only six-and-a-half months later!

Common types of cases involving women include those involving fornication, illegitimacy, and other sexual crimes; debt, trespass, and slander; assault and domestic violence; and inheritance disputes. Although many women were hampered by coverture, a few had notable triumphs. In 1765 Phillis, a freewoman of New Haven, won £200 in damages against John Clark of Colchester, who assaulted and falsely imprisoned her. In 1716 Mehittabel Whitehead of Branford submitted a written rebuttal to a slander charge made against her by fellow townsman Micah Palmer that resulted in a favorable verdict and the recovery of her court costs.

The specter of witchcraft also continued to haunt women into the 18th century. While the last known criminal trial occurred in 1697 and the last known executions for witchcraft in Connecticut took place in 1662-1663, according to Chief Attorney Sandra Norman-Eady and Librarian Jennifer Bernier’s December 18, 2006 report to the Connecticut General Assembly (Connecticut Witch Trials and Posthumous Pardons), people continued to fear witches. In 1742 a widow named Elizabeth Gould sued Benjamin Chittenden for slander for claiming she was a witch. Both the plaintiff and defendant resided in the North Parish of Guilford. Chittenden’s accusation was stunning and lurid: “he did believe She… was a Witch and had Reason to believe it because She… rode down here… & came in & got upon my Breast… & Lay upon me so hard as to make the Blood flie out at my Mouth & Nose.” Gould alleged that Chittenden was “Envious at the Happy Estate of the Plaintiff & minding to vex & grieve her unjustly, & her to Slander,” and she poignantly described how his accusation rendered her an outcast in their community, bringing her into “Disgrace Contempt, & Abhorrence, as well as [depriving]her of the Society Traffick & both Pleasant & Necessary Converse of her Neighbours.”

Unfortunately, the court found Gould’s plea “insufficient” and awarded Chittenden the recovery of his court costs. Although the reasoning for this verdict was not given, it is likely that Gould’s status as a widow damaged her credibility. As Allegra di Bonaventura observed in her book For Adam’s Sake: A Family Saga in Colonial New England (W.W. Norton, 2013), “a lone woman, widowed or unmarried, was an inherently suspect figure—particularly vulnerable to charges of immorality, or even witchcraft.”

What We’ve Learned

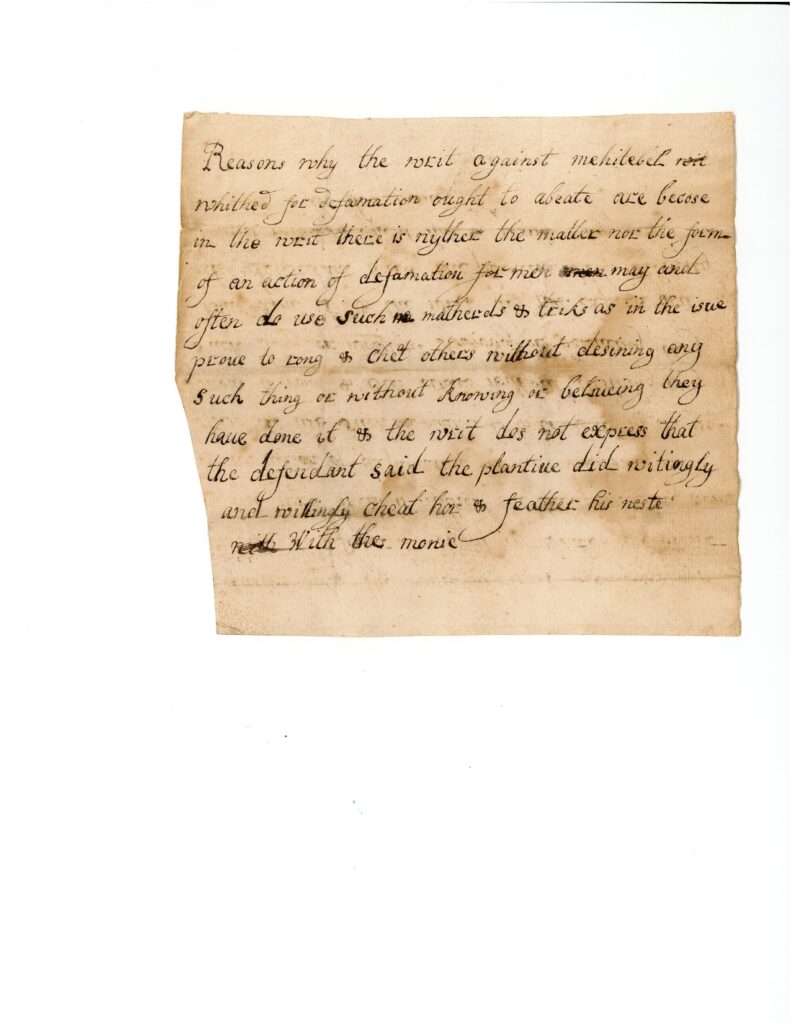

Mehittabel Whitehead’s written rebuttal to the slander lawsuit brought by Micah Palmer, 1716. Palmer claimed that she falsely defamed him for abusing his role as administrator of an estate. Whitehead argued “there is nyther the matter nor the form of an action of defamation for men may and often do use such [methods]& triks” and she insisted that “the planti[ff]did witingly and willingly cheat her & feather his neste With the monie.”

While the court records often raise more questions than answers about the lives of specific individuals such as Elizabeth Gould, Nelle, Hanah, Susan, and Sharper, we can make some general observations about the lives of women, African-descended, and Indigenous persons in colonial and early American Connecticut—with the caveat that it is difficult to ascertain what these groups truly thought or felt about their circumstances, as their voices were often omitted from the official record. In the majority of court cases the narrative voice is that of the court clerk or justice of the peace. Though there are a few direct transcriptions of witness testimonies, the situations of women, African-descended, and Indigenous persons were most often summarized, spoken about, and described through the perspective of white, elite, Euro-descended men. The nature of these legal disputes and the narrative structure of these records demonstrate a society that adhered to a strict hierarchy of power in which white women were dependent, free Black and Indigenous persons were subordinate, and enslaved Black and Indigenous persons were property. However, individuals in these groups still used the courts to fight for justice whenever they feasibly could—and sometimes they even triumphed.

Sarah J. Morin is a project archivist at the Connecticut State Library. She has processed institutional and manuscript collections at the Connecticut State Library, University of Connecticut, and two historical societies in Massachusetts.

Learn More!

To aid researchers the Connecticut State Library has published a subject guide about the eras in which these cases occurred. A CSL blog chronicles noteworthy cases and discoveries in the court records. Find both at libguides.ctstatelibrary.org/archives/uncoveringnewhaven.

Follow the project’s progress on Instagram @ctstatelibrary, Facebook @CTStateLibrary, and Twitter@LibraryofCT.

Records digitized to date and a discussion of the digitization process and scanning criteria are viewable on the Connecticut Digital Archive (CTDA) at ctdigitalarchive.org/.