By Frederick A. Hesketh

Connecticut Explored Inc. SPRING 2008

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

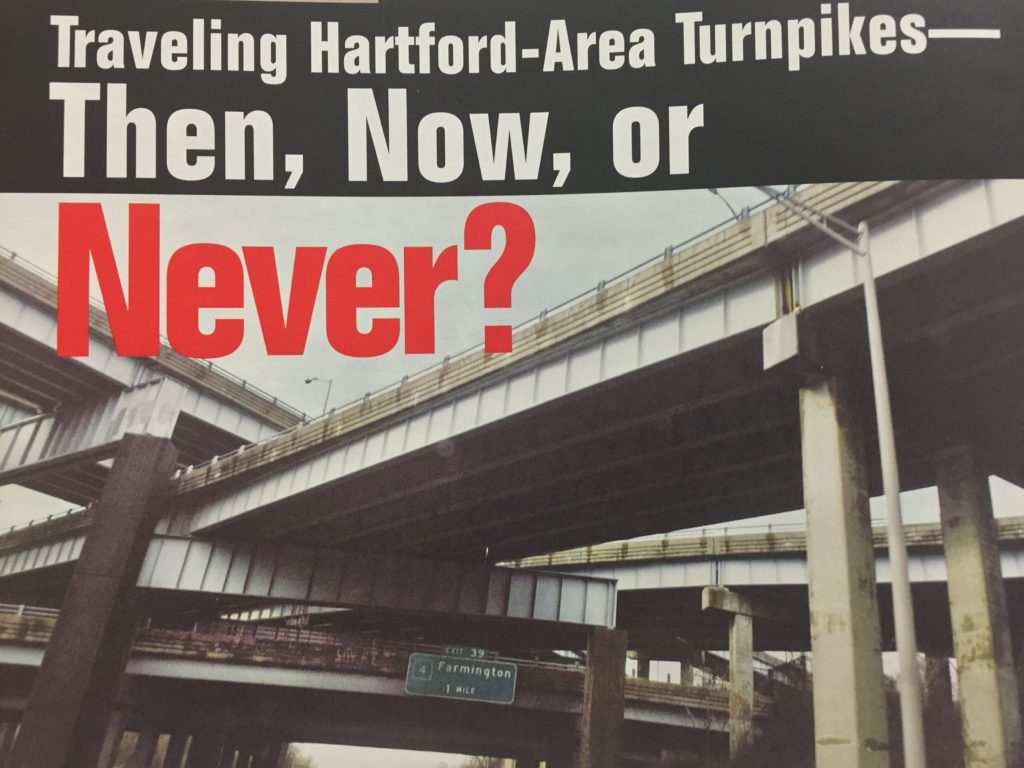

Close observation as you drive the highways in and around Hartford, particularly while sitting in rush-hour traffic on I-84 or I-91, will undoubtedly raise questions about why the highways are configured the way they are. Most puzzling perhaps are Farmington’s stacks of highway exits and entrances that lead nowhere and westbound I-291 in Windsor that leads traffic to a two-lane highway terminating at a traffic signal. Retired traffic engineer Frederick A. Hesketh offers a short history of the development of the highway system in Connecticut and unravels the mystery surrounding some of Greater Hartford’s unrealized highway plans.

Close observation as you drive the highways in and around Hartford, particularly while sitting in rush-hour traffic on I-84 or I-91, will undoubtedly raise questions about why the highways are configured the way they are. Most puzzling perhaps are Farmington’s stacks of highway exits and entrances that lead nowhere and westbound I-291 in Windsor that leads traffic to a two-lane highway terminating at a traffic signal. Retired traffic engineer Frederick A. Hesketh offers a short history of the development of the highway system in Connecticut and unravels the mystery surrounding some of Greater Hartford’s unrealized highway plans.

A Short History of the Highways

“In many New England towns will be found an old road locally known as ‘the turnpike,’ or the ‘old turnpike,’ over which are hovering romantic traditions of the glory of stage coach days,” wrote civil engineer Frederick J. Wood, author of “The turnpikes of New England” in 1919. The word “turnpike” derives from the system used to collect tolls. A pike is a long stick, usually with a point at one end. From the 16th to the 19th century, a pike was set across certain private travel ways to stop travelers from passing. Payment of a tariff, or toll, caused the operator to pivot the stick—or “turn the pike”—to allow passage. These devices became known as turnstiles, and the roads, turnpikes, of which there were several connecting Hartford to distant parts of Connecticut.

Those early toll roads were built by private corporations. An enterprising person or business would petition the state for the right to construct and/or maintain a road and be granted the right to collect tolls for their efforts. Between 1792 and 1858, 112 turnpike corporations formed in Connecticut. Many of the roads they managed still exist today (albeit much improved), connecting Hartford to New Haven and other major cities in the state and the region: US 44 and CT 21 to Boston, US 44 to Albany, US 5 to New Haven, CT 189 to Granby, CT 2 to New London, US 6 to Farmington and Bristol, and CT 30 and CT 74 to Tolland.

Decisions regarding toll roads’ location were not lightly made. State records indicate abundant controversy, most of which centered on the political clout of turnpike promoters versus private citizens who either favored or opposed a location, depending on whether they would benefit or, as some citizens feared, experience economic stagnation if the turnpike passed them by.

By the early 1900s, local governments figured out how to tax road use, largely replacing private tolls as a source of revenue for maintaining the roads. Still, in the first decade of the 20th century, of the approximately one million miles of road spread out across the country, virtually none were paved. Horses found such roads acceptable, but Henry Ford’s 1908 “motor car” often found them impassable quagmires of mud. The advent of the automobile created the impetus for the largest transformation of turnpikes in more than 100 years.

Early in the 20th century, following twenty years of posturing and lobbying by farmers, mail carriers, and members of Congress, state and federal governments began to assume responsibility for providing and maintaining highways. State taxes, supplemented by federal aid for regional highways, replaced the tolls, though some state roads were still funded with toll revenue. In 1938, just before the U.S. entered World War II, the State of Connecticut opened one of the earliest “parkways” in the nation. The Merritt Parkway won accolades for the beauty of its roadsides and the unique design of each of its overpass bridges. The less-celebrated Wilbur Cross highway soon followed.

During World War II regular highway finance programs were suspended as resources were diverted to the war effort. With the end of the war in sight, though, the Federal-Aid Highway Act of 1944 was passed in anticipation of the transition to a postwar economy and to prepare for the expected growth in automobile traffic.

Sure enough, after the war people moved from cities to the suburbs in record numbers, and people began using private automobiles to commute to work and to go shopping. Use of mass transit, which had peaked during the war, fell off. Every family wanted a car—or two.

Highway Planning Gains Momentum—and Hits a Wall

A 1945 report by the Connecticut Highway Department proposed a nine-mile expressway from the west end of the Bulkeley Bridge (built in 1908 and named for Morgan G. Bulkeley, a Hartford insurance executive, Hartford mayor from 1879 to 1887, Connecticut’s governor from 1889 to1893, and United States senator from 1905 to 1911), generally along the route that later became I-84, to Corbins Corner (near the present West Farms Mall), with improved roads extending further west to connect to Route 6 and to Route 4. The department promised that “motorists will travel in and through our cities with a freedom and degree of safety heretofore impossible” and that “Great community and business benefits will result from improved traffic conditions.”

In the next decade President Dwight D. Eisenhower promoted the National System of Interstate and Defense Highways. As a young officer following World War I, Eisenhower had traveled cross-country in one of this country’s first transcontinental motor convoys. That experience, coupled with his observations of German military movements over that country’s vast autobahn system during World War II, led Eisenhower to establish a Highway Trust Fund to construct a cross-country network of highways that would enable the rapid movement of military equipment to counter any future attack on the United States.

Eisenhower argued that the existing roads had “…appalling inadequacies to meet the demands of catastrophe or defense, should an atomic war come.” The Eisenhower highways would have almost 18 feet of vertical clearance at underpasses, 3 feet higher than previous standards dictated. Such clearance would allow the movement of heavy weapons and defensive rocket launchers.

In his communications to Congress urging support for his program Eisenhower stressed “the need to evacuate cities in the event of an atomic attack” and said the present highway system would be “the breeder of a deadly congestion within hours of an attack.” To ensure that the program was implemented, Eisenhower’s funding formula provided that 90 percent of the costs would be borne by the federal government. Previous federal-aid highway funding had been split evenly between the federal and state governments.

Many medium-sized and large cities were to be served by two or more interstate routes, typically one north-south and one east-west. Such interregional routes would intersect at the city and all would pass within a convenient reach of the large central business section. Such a pattern afforded easy access to the city and accommodated both normal egress and emergency evacuation.

By 1957 though, the Interstate Program added the concept of circumferential routes or ring road around the city to remove the “through” traffic and added congestion from the city centers. The location of these routes would be such that in no case would the distance around the city be materially greater than the distance along the through route.

In Hartford, the north-south I-91 and the east-west I-84 both run through or adjacent to the city center. The 85-mile I-84 was constructed in the 1960s and occupies the corridor envisioned in Hartford’s pre-World War II east-west expressway. I-91 follows the route of earlier highways from the 1940s and 1950s—the “Dike Highway,” North Meadows Highway, and others—that were extended to Bradley Field and Windsor Locks in the 1950s. It was first given the designation of I-91 early in 1961. Some will argue that it has been under construction or reconstruction continuously since its inception.

A circumferential, to be numbered I-291, was approved by the federal government in 1957. It was to be a 27-mile western loop around the Hartford area from I-91 in Rocky Hill, between exits 23 and 24, west through Newington and New Britain to a four-level interchange (now known as the “Stack”) near the Farmington-West Hartford town line at I-84.

From there, I-291 was to continue north through West Hartford to Simsbury Road (Route 185) with an interchange at North Main Street (Route 218) and then turning east through Bloomfield generally south of and parallel to Cottage Grove Road to Windsor, where it would rejoin I-91 at Exit 37. The section of I-291 from I-91 at Windsor east to I-84 in Manchester was not part of the original plan but was added later; ironically, it is the only section of I-291 north of I-84 that was ever built. To complete the circumferential, the 1957 federal approval also included an I-491 from Rocky Hill to East Hartford; if built, it would have completed a 360-degree circumferential of Hartford to carry interstate traffic.

Why was the planned I-291 largely abandoned?

The Federal Highway Act of 1956 introduced mandatory requirements for citizen input and a greater consideration of issues relating to air and water pollution, preservation of parkland, wetlands, and historic sites, and “the overall ecological balance in communities and their capacity to absorb disruption” early in the planning process. This requirement officially opened the process for the first time, mandating public hearings to solicit comments from those affected by the proposed roadways.

While the building of I-84 and I-91 between 1945 and 1958 stirred some controversy and emotion, the planning and design process was sufficiently well received that both were constructed and put in operation as planned. In 1959 and 1960, public hearings in towns along the “corridor” of the planned Interstate 291 in Rocky Hill, Newington, and Wethersfield were also generally positive. Most public comments were related to interchanges and suggestions for relocating certain portions.

Residents and town officials throughout the region apparently were satisfied with Highway Commissioner Howard Ives’s assurances during those early hearings that the highway “will have a positive effect (and) will relieve the traffic on existing local streets and the main arteries through the town(s).” Ives told residents at public hearings, “After completion of these expressways you will find these (local) routes freed of the congestion so that they may again adequately serve your local shopping and business needs.”

Planning and expansion continued. By 1967, the Capital Region Planning Agency (CRPA)’s projections indicated that completion of the planned interstate highway network alone would constitute only the “minimum network” required to handle traffic in the year 2000. The agency recommended several additional roadways to accommodate that anticipated traffic, including a new Route 44 alignment extending west from a junction with I-291 near the Bloomfield-West Hartford town line to Canton and beyond. Such a route would have provided an alternate for Avon Mountain truck traffic.

Meanwhile, through the 1960s, state residents increasingly adopted a “Not in my backyard” stance toward highway development. The required corridor and design public hearings provided a forum for airing such concerns. In Rocky Hill and Newington, the formerly positive public response began to dissolve. Residents opposed the construction of the southwesterly section of I-291, citing impact on neighborhoods and on developed properties in those communities.

Barbara Surwilo of Rocky Hill found that her newly acquired home would be among those surrounded by freeways. Surwilo, a biochemist, asked, “Why 291?” and led a group by that name through a decade-long battle, leading protests at public hearings and legal proceedings. The group’s protest over a ConnDot Environmental impact report caused a work stoppage on a section of road literally under construction and the eventual removal of a partially completed interchange in Rocky Hill.

Heavy opposition surfaced in West Hartford as residents expressed concern for the safety of the water supply in the MDC reservoirs and about the proposed road’s impact on residential neighborhoods in West Hartford and Bloomfield. West Hartford resident Charlotte F. Kitowski, a nurse, turned her energy to opposing the new highway, chairing the Committee to Save the Reservoir. She held countless rallies, gathered thousands of signatures on petitions, stirred anti-highway sentiment, and advocated mass-transit alternatives. Surwilo and Kitowski quickly became well known to politicians, highway officials, and reporters as they fought to save the neighborhoods and the reservoir from the I-291 encroachment.

In November 1973, local opponents cited deficiencies in the environmental-impact reports that ConnDot had developed to support the project and won a court injunction against further planning for the Newington-Rocky Hill section of I-291. The injunction was eventually lifted, though, and in the fall of 1977 the DOT held public hearings in each of the seven towns in the southwest quadrant of I-291. Surwilo, as the leader of those opposed to I-291, attended at least six of those hearings, and her comments and questions fill more than 120 pages of the hearing transcripts. Her comments indicated a complete grasp of details on the plans. Her command of the material drew praise even from the frustrated officials she was addressing.

Kitowski enjoyed a similar reputation for her opposition to the I-291 plans north of I-84. Her “Save the Reservoir” campaign led to the abandonment of the northwest quadrant of I-291.

Lewis B. Rome, the republican mayor of Bloomfield, appeared before the West Hartford town council on September 25, 1969 to report that both the Bloomfield town council and Bloomfield Planning and Zoning Commission favored the construction of I-291 and to urge West Hartford officials to join in that support. During the election that November however, six of the seven council members chose not to seek reelection that fall. Democrats won control of the council in Bloomfield and withdrew the town’s support for I-291. Governor Thomas J. Meskill succeeded John Dempsey, who had been governor for 10 years, in January 1971 and ordered studies of a route further to the west of the reservoirs and west of the Talcott Mountain ridge, but that route increased the mileage beyond that which the federal government would approve for a circumferential. Meskill could have his cake and eat it too—he publicly favored the highway, all the while knowing it would not be built because the federal authorities would not fund the longer route.

Whither I-291?

So how did it all turn out? Route 9, built with 50-percent federal funding, was completed in 1992 and serves as a sort of circumferential for traffic in the southwest quadrant, interchanging with I-91 in Cromwell south of the planned interstate route in Rocky Hill and Newington. Sections of Route 9 north of New Britain follow the original planned corridor of I-291 to join I-84 at the “Stack” near the West Hartford-Farmington line.

Traffic from the east on I-84 turning onto I-291 in Manchester can travel as far as I-91 at exit 35 in Windsor. Beyond I-91, that traffic is sent on a short two-lane freeway to Connecticut Route 218 in Windsor near the Bloomfield town line.

Today, interstate travelers and commuters regularly find themselves stuck in heavy traffic on I-84 and I-91 as they enter and exit the capital city—a situation that I-291 was designed to alleviate. The portion of that traffic that both originates in and has destinations outside of the I-291 ring would not be traveling along the interstate highways through Hartford if I-291 had been constructed as a circumferential.

A June 7, 2007 report, “Transportation in Connecticut, The Existing System,” prepared by the Connecticut Department of Transportation in cooperation with the Federal Highway Administration, estimates that by the year 2025 virtually the entire interstate highway system in Hartford, West Hartford, East Hartford, Wethersfield, and Windsor will be at or approaching capacity.

Six or eight additional lanes that were planned in the I-291 corridor west and north of Hartford and in the I-481 corridor between Wethersfield and East Hartford will not be there to relieve the congestion. The Rocky Hill and Newington parks may still exist, and the West Hartford MDC reservoirs will still produce water. But most of us on the interstates attempting to get home to take the kids to the park or to take a dip in the pool supplied by MDC water will be sitting in a traffic jam.

We have to ask ourselves today if Eisenhower’s dream has come true or if we are still in a situation where, as he described in 1954, “the annual death and injury toll, the waste of billions of dollars in detours and traffic jams, the clogging of the nation’s courts with highway-related suits, the inefficiency in the transportation of goods, and the appalling inadequacies to meet the demands of catastrophe or defense, should an atomic war (or, a 2007 threat he never anticipated, a terrorist attack) come.” Or do we take comfort in the results achieved by public protest that valued intact communities and neighborhoods over speedy transportation?

Explore!

Read more stories in the Spring 2008 issue.