By Donald W. Rogers

Linus Yale, Jr., inventor of the modern pin-tumbler cylinder lock, History of the Trademark “Yale.” image: Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library

Henry R. Towne, professional engineer and principal owner of Yale & Towne Manufacturing Company, History of the Trademark “Yale.” image: Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library

Henry R. Towne, professional engineer and principal owner of Yale & Towne Manufacturing Company, History of the Trademark “Yale.” image: Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library

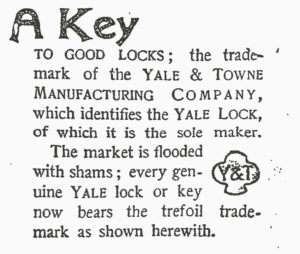

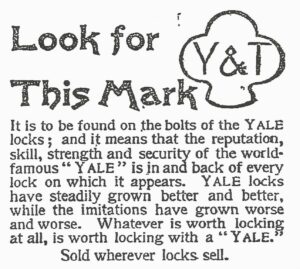

In 1892 the Yale & Towne Manufacturing Company of Stamford, Connecticut, blitzed New York and Connecticut newspapers with advertisements that announced the trademark “YALE” for the padlocks, door latches, and other hardware that the firm made and sold. Yale & Towne was the sole manufacturer of the “Yale Lock,” the ads noted, but “the market is flooded with shams” and “worthless imitations.” Consequently, the ads advised buyers to look for the distinctive “Y&T” trefoil or the word “YALE” stamped on products to ensure that they got a “genuine Yale lock or key.” “Look for This Mark,” the ads urged potential customers.

Nowadays we are plenty familiar with trademarks. They saturate our modern consumer economy, from the distinctive logos on Apple electronic devices to insignias on clothing. When Yale & Towne’s advertisements began to appear, though, trademarks were acquiring a new importance. Their growing use signaled a distinctive phase of Connecticut’s—and the nation’s—industrial growth, when mass production and mass marketing firms using trademarks came to dominate state and national economies that previously had consisted of a decentralized array of small and medium-sized firms manufacturing and selling on the local level. Yale & Towne’s trademark exemplifies the legal side of that development.

Product markings originated in antiquity with the literal branding of animals to identify ownership; they appeared later on pottery, masonry, and tile to designate creators, then proliferated as identifiers for goods shipped overseas, and eventually warrantied workmanship in crafts like baking and silversmithing. The industrial revolution ushered in the modern use of “trademarks”—names, symbols, or letters that associate goods with their makers, as opposed to patents or copyrights, which protect the intellectual creations of inventors, authors, and artists. Industrial growth shifted manufacturing into large factories, increasing the need for mass advertising to sell mass quantities of goods. Trademarks helped firms like Yale & Towne distinguish their goods in the mass-marketing process.

1892 newspaper display ads introducing Yale & Towne Manufacturing Company’s “YALE” Trademark. The New York Times, March 7, 1892 and April 29, 1892

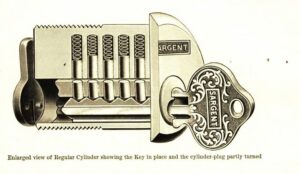

Diagram of Pin-Tumbler Cylinder Lock by Sargent Company, illustrating the device originally invented by Linus Yale Jr., but produced by many firms after his patent expired, Sargent Company Catalog, 1910, in Sargent Company Records. image: Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library

In the Anglo-American world a body of law protecting trademarks originated in the 1600s and blossomed in the late 1800s. Legal experts say it emerged from the judge-made common law tort of fraud and deceit—the fraudulent appropriation of another merchandiser’s mark to “pass off” one’s goods as those of that other. For example, in the 1872 case of Meriden Britannia Company v. Charles Parker the Connecticut Supreme Court ruled that small producer Parker infringed upon the trademark “Rogers” that Meriden Britannia had lawfully established and stamped on its plated silver spoons and forks by placing the mark “C. Rogers Brothers” on his own silver flatware. According to the court, Parker’s mark so closely resembled Meriden’s that it was “calculated to deceive” and “did deceive” unwary purchasers.

By the early 1900s trademark law had gained nuance, even as federal legislation came slowly. According to trademark legal scholar J. Thomas McCarthy in Trademarks and Unfair Competition 2nd Ed. (Lawyers Co-Operative Publishing Company, 1984), judges shifted focus from the outright theft of trademarks to the deceptive use of similar marks that “confused” buyers. Legal scholar Margreth Barrett in “Finding Trademark Use,’” Wake Forest Law Review(2008) adds that judges also began distinguishing exclusively-protected trade markings from trade names that, while not exclusive, were protected from “unfair competition” by rival firms in the same business that used similar names to mislead buyers. Federal law was sluggish in codifying these principles. The U.S. Supreme Court struck down the first national trademark legislation in 1879, and the U.S. Congress did not pass another covering both domestic and foreign trade until the Trademark Act of 1905. That measure mostly just codified common law, but it also launched national trademark registration at the U.S. Patent Office.

In this fluid context, Connecticut spawned America’s lock-making industry. According to historian Thomas Hennessy in Locks and Lockmakers of America 3rd Ed. (Locksmith Publishing Co., 1997) dozens of Connecticut lock makers spun off the state’s 19th-century clock and hardware trades to produce trunk, cabinet, bank, door, and pad locks. By the late 1800s big lock manufacturers prevailed, particularly the Eagle Lock Company (Terryville), Corbin Cabinet Lock Company (New Britain), and Sargent Company (New Haven).

In this fluid context, Connecticut spawned America’s lock-making industry. According to historian Thomas Hennessy in Locks and Lockmakers of America 3rd Ed. (Locksmith Publishing Co., 1997) dozens of Connecticut lock makers spun off the state’s 19th-century clock and hardware trades to produce trunk, cabinet, bank, door, and pad locks. By the late 1800s big lock manufacturers prevailed, particularly the Eagle Lock Company (Terryville), Corbin Cabinet Lock Company (New Britain), and Sargent Company (New Haven).

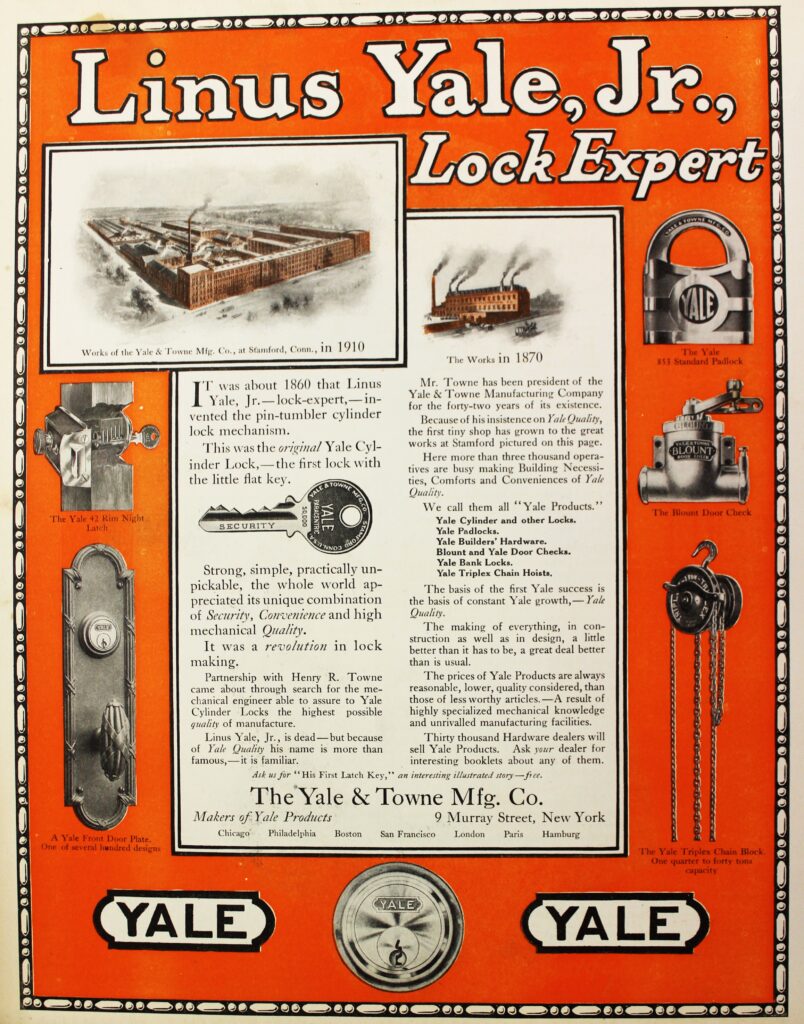

Advertisement in The Saturday Evening Post, exemplifying how Yale & Towne Manufacturing Company rooted its hardware brand name “Yale” in Linus Yale Jr.’s invention, undated, Yale & Towne records. image: Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library

Yale & Towne was another. According to company histories held in Yale & Towne records at the Archives and Special Collections department of the University of Connecticut Library , the business originated with Linus Yale Sr., a distant relation to Yale College founder Elihu Yale. He set up a small lock business in Newport, New York in the 1840s, then passed it to his son, Linus Jr., who gave up portrait painting to open his own small lock shop in Philadelphia. To meet public demand for cheaper and less easily picked devices, in 1865 Linus Jr. patented the modern “pin-tumbler” cylinder lock modeled after ancient Egyptian technology. Widely used today, this clever design was more secure, easily adaptable, and cheaply mass-produced. It needed only a small, flat, serrated key to operate. Linus Jr. introduced it in banks, then applied it to padlocks.

To mass-produce pin-tumbler locks, Linus Jr., established a factory in Shelburne Falls, Massachusetts in 1861.In 1868 he joined with Henry R. Towne of Philadelphia to found the Yale Lock Manufacturing Company in Stamford, Connecticut. Younger by two decades, Towne was not a craftsman like the Yales, father and son, but rather a professional engineer educated at the University of Pennsylvania. He is well known to business historians today as a leader of the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME) and a major exponent of managerial reform in big industry. As fate would have it, his partner Linus Yale Jr. died of heart disease just as he and Towne were about to move to Stamford. Subsequently, Towne secured total ownership of the new firm and in 1883 reorganized it as the Yale & Towne Manufacturing Company (Y&T).

Late-19th-century business conditions steered Y&T toward trademark use. Y&T grew rapidly, absorbing other firms in the process. Meanwhile, Towne rose as ASME president and promoted his own managerial improvements, many at Y&T, including the use of mass marketing. As it grew Y&T faced a cutthroat business culture wherein lock makers commonly filched each other’s designs, reflecting, as Second U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge William James Wallace put it in Yale & Towne v. Adler (1907), “a laxity of business morality among lock manufacturers.” Simultaneously, many companies introduced pin-tumbler locks of their own after Linus Yale Jr.’s patent expired 1885. In this context, lock advertisements and burglary stories in newspapers indicate that manufacturers and the public alike saw “Yale locks” as pin-tumbler devices made by any manufacturer, not as a brand. In Connecticut’s infamous 1891 “crowbar” incident, for example, newspapers such as The Press of Stafford Springs described how Democratic Comptroller of Connecticut Nicholas Staub tried to bar Republican Governor Morgan Bulkeley from the executive office during an electoral dispute by firmly securing the door with a “Yale lock,” prompting Bulkeley to obtain a crowbar to pry the door open. Newspapers did not say explicitly that the “Yale lock” deployed in this instance was a Y&T product, so they left unclear whether their use of the term “Yale lock” meant a specific brand or just any sturdy lock.

As a rising mass-production firm needing to ensure a high volume of sales in that tough economic environment, Y&T turned to trademark use as a marketing strategy. According to company histories in Y&T archives, Towne first tried stamping the word “Yale” on Y&T’s products as part of the manufacturing process to distinguish them from those made by competitors. This led to Y&T’s 1892 newspaper advertisements. With passage of the federal Trademark Act of 1905, Y&T launched a legal campaign to establish exclusive use of “Yale” in the hardware trade. The firm promptly registered the term with the U.S. Patent Office and other patent offices around the world. Y&T then dispatched attorneys to warn other companies against using the term “Yale,” and, if necessary, to take them to court, as Y&T had already done in patent infringement cases.

Company records held in the Archives and Special Collections department of the University of Connecticut libraryshow that Y&T waged its legal campaign vigorously from the start. In Yale & Towne Manufacturing Company v. Benjamin S. Alder (1907) Y&T persuaded the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals in New York State to rule that the Fraim Company of Lancaster, Pennsylvania so duplicated the “form, size, coloring, [and]lettering in details” of Y&T’s No. 805 padlock that customers were likely to buy Fraim products “supposing them to be padlocks of [Y&T].” Similarly, in Yale & Towne Manufacturing Company v. Eagle Lock Company (1910) Y&T got a New York court to declare that the Eagle Lock Company of Terryville, Connecticut so closely copied the “shape, size . . . general appearance and dressing” of Y&T’s night latch cylinder heads that buyers would be fooled into purchasing Eagle devices. In both cases, Y&T contested not outright theft of its registered markings but rather “unfair competition” through deceptive use of similar markings.

Even more vexing than competitors’ devious use of “panel marks” was continued popular reference to a “Yale lock” as any manufacturer’s pin-tumbler device. In “The Prototype of the Yale Lock,” Scientific American, August 16, 1913, for instance, Walter Schumann described a “Yale lock” as a modern lock mechanism rooted in ancient technology. Y&T attorneys apparently intervened, because just a month later the magazine issued a clarification stating that the term “Yale lock” “is used to designate not only any type of lock, but any lock of any type made by [Y&T].”

The Sargent Company of New Haven, however, did not yield so easily. A major Connecticut hardware manufacturer with large domestic and overseas padlock sales, that firm prominently engraved the word “SARGENT” on its products, but business correspondence shows that it also routinely used the term “Yale lock” with retailers and customers to refer generally to its own pin-tumbler devices. If Y&T kept the term to itself, then Sargent would lose a lot of business. Hence, Sargent’s records in Archives and Special Collections at the University of Connecticut demonstrate that when Y&T sued the firm in U.S. district court in 1911 to stop its use of the term “Yale lock” in everyday business, Sargent and its lawyers carefully researched whether to put up a fight. From old Y&T catalogues, Sargent likely found out that Y&T had genuinely been using “Yale lock” as a brand, even though it also learned from salesmen and mechanics, from sales practices in hardware stores, and from numerous patent applications not filed by Y&T, that there was broad commercial treatment of “Yale lock” as a type of lock, not a trade name. Given Y&T’s strong apparent claim, Sargent decided to settle. In 1912 it agreed to stop using the term “Yale lock” forever in return for Y&T’s agreement to drop its lawsuit.

Through the next two decades Y&T aggressively sought “corrections” from other firms, as documented by its booklet History of the Trade-Mark “Yale,” published in four editions between 1914 and 1930. In this booklet Y&T insisted that it had a legal right like all manufacturers to establish a distinctive trademark for its products and that its own registered trademark “Yale” was especially appropriate, because it originated in Linus Yale Jr.’s patent. The booklet chronicled more than a hundred “adjudications and settlements” that Y&T won from 1907 to 1929 to “warn” other companies against encroaching on the trademark “Yale.”

Cases cited in History of the Trade-Mark “Yale,” were wide-ranging. Some appeared to reveal actual abuse of Y&T’s trademark, with businesses assuming the “Yale” name or selling locks labeled “Yale.” Many involved key blanks made by other manufacturers such as Corbin Cabinet Lock that were misleadingly sold as “Yale keys,” since they fit Y&T locks. A few involved deceptive variations on the “Yale” name, such as “ELI,” “JALA” or “WALE.” Yet a good number suggested unintentional encroachment by manufacturers who produced locks based on the “Yale system,” the “Yale type,” the “Yale principle,” or, in Italy, “Tipo Yale,” a reflection of the persisting view that a “Yale lock” was a type of lock, not a brand. When Y&T’s lawyers contacted these firms, many “apologized for the oversight,” according to the booklet. In the 1910s, moreover, Y&T initially targeted domestic merchants and manufacturers, but in the 1920s it turned to companies in Europe, Latin America, Australia, and South Africa. The shift coincided with Y&T’s growth as a multinational corporation engaged in overseas markets and business acquisitions.

A crucial legal issue running through all of these cases was the exclusivity of Y&T’s “Yale” trademark. By law, it did not apply to numerous entities outside of Y&T’s line of business, like Yale University. But could Y&T bar its use by all other commercial firms? History shows that Y&T challenged many small merchandisers of quite unrelated goods such as coat hooks, handbags, sporting goods, and razors for their use of “Yale.” In Yale Electric Corporation v. Robertson(1928), however, the U.S. Second Circuit Court of Appeals drew the line. The case arose from the New York-based Yale Electric Corporation’s (YEC) unsuccessful application to register the “Yale” name to sell flashlights and batteries. A U.S. Patent Office examiner had ruled against YEC on grounds that there was enough danger of “confusion” between YEC’s and Y&T’s products to deny the request. When YEC eventually appealed that decision to the Second Circuit, Judge Learned Hand sustained the rejection but also identified a limit to Y&T’s rights. He observed that it made no sense to deny the same trade name to makers of different goods, but he added that “trade conditions” could create unfair confusion, such as here where YEC and Y&T each sold products in the same hardware stores. In that situation YEC could unfairly benefit from Y&T’s good name by using “Yale.”. Hand thus upheld the prevalence of Y&T’s trademark, but on grounds that the firm’s claim to “Yale” rested on fair business conditions needed to protect its sales and reputation.

The Depression-era Connecticut Supreme Court decision in Yale & Towne Manufacturing Co. v. Rose (1935) further clarified matters. Here Y&T objected to the name of “Yale’s Hardware Store,” founded in 1924 on Front Street in Hartford by Russian-born Jewish immigrants Yale and Charles Rose. The store’s name apparently came from its co-founder Yale Rose, but Y&T insisted formulaically that the Rose brothers deliberately adopted the name to piggyback on Y&T’s reputation. The Connecticut court firmly rejected Y&T’s claim as unproven by evidence and added that the law favored entrepreneurs registering their own proper names. Neither did the court find evidence to support Y&T’s complaint that “Yale’s Hardware Store” jeopardized its business, given that the store was an obscure little enterprise. In this case, Connecticut’s court ruled, Y&T’s trademark could not prevail, because Yale’s Hardware Store was not a commercial threat and was reasonably named after its founder.

Such a lawsuit brought by a giant multinational corporation like Y&T against a tiny urban hardware shop highlighted a modern problem with trademarks: their potential misuse as instruments of monopoly power. Trademark law historians J. Thomas McCarthy in Trademarks and Unfair Competition and Sandra Levin in “The Origins of the Lanham Act,” Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues (2010) note that corporate and legal conservatives in the 1920s had grown discontented with the 1905 Trademark Act and its lax enforcement and that liberal New Dealers in the U.S. Justice Department in the 1930s grew alarmed that trademarks might allow big firms to evade antitrust legislation. Eventuallythese concerns led to the 1946 Lanham Act, the U.S.’s modern trademark statute, including a provision that voids trademarks that violate antitrust laws. Antitrust issues were not central to Y&T’s case, but the threat the company’s trademark claims posed to many small firms reflected the growing dominance of big corporations in Connecticut’s 20th-century economy.

“Yale’s Hardware Store on Front Street, Hartford, targeted by a Yale & Towne lawsuit for unfair use of the term ‘Yale,’ circa 1935, Yale & Towne Records. image: Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library.

In hardware, the trademark “Yale” lives on, though Y&T has disappeared. Y&T had a huge Stamford plant and European subsidiaries by the 1920s, but after Henry Towne’s death in 1924, his successors dismantled the Stamford divisions in the 1950s and merged with Cleveland’s Eaton Corporation in 1963, giving way finally to Swedish ASSA ABLOY ownership in 2000. Some places like Great Britain retain “Yale lock’s” old popular meaning as a generic type of front door latch. Yet ASSAS ABLOY still maintains Y&T’s “Yale” trademark, and reference works like the Cambridge Dictionary today still define “Yale lock” as “a brand name for a type of lock, especially for doors, that is cylinder-shaped and is operated by a flat key”– that is, as a trademarked device based on Linus Yale Jr.’s invention. Even a Google search today will yield results showing that “Yale lock” is a specific brand of locks and hardware.

Donald W. Rogers is Adjunct Lecturer in History, Emeritus, at Central Connecticut State University. He thanks staff at the New Britain Industrial Museum and at Archives and Special Collections, University of Connecticut Library for their assistance.

Learn More!

William Devlin, “When Connecticut’s Rivers Ran Black,” Connecticut Explored, Spring 2021