By Gene Leach

(c) Connecticut Explored, Summer 2013

CLICK HERE TO READ AS IT APPEARED IN THE ISSUE

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

It was fun while it lasted. For four summers a flamboyant amusement park cavorted on twelve acres of West Hartford just over the Hartford line, like a kid razzing a truant officer. Colt’s Band played, “airships” flew, riders shrieked, skaters rolled, the whole place rocked—except for the bottom line. That sank like a stone.

The strip of West Hartford along Hartford’s western edge first became a “pleasure ground” when a harness-racing track opened there in 1873-1874. This Charter Oak Park prospered. It joined the trotters’ “Grand Circuit” in 1876; the redoubtable president of Aetna Morgan Bulkeley—later mayor of Hartford, governor of Connecticut, senator, and first president of baseball’s new National League—owned it for a while.

But the fortunes of Charter Oak sagged when the state legislature cracked down on gambling in the mid-1880s and continued to sag even though its new owners, two bookies, took bets on the sly. Pressed by local police and hurting for cash, the Charter Oak proprietors sold a 12-acre parcel of their real estate to a New Haven construction company with a dream—to replicate in Hartford the nickel-minting Coney Island amusement parks Steeplechase (1897) and Luna (1903).

Other Coney imitators were popping up all over the country, including one Connecticut park that predated West Hartford’s Luna by a few years. According to an article on the Bridgeport History Center’s Web site, two entrepreneurs built “Pleasure Beach” on a 37-acre island at the mouth of Bridgeport Harbor in 1902. Three years later the owners of Coney’s Steeplechase bought the Bridgeport facility and operated it until uneven attendance prompted them to sell in 1910. West Haven’s legendary Savin Rock opened as a summer resort in the 1870s but did not acquire the trappings of an amusement park until around 1908, according to Palisades Amusement Park: A Century of Fond Memories (Vince Gargiulo, self-published, 1995). Lake Compounce, a bucolic retreat for picnickers that operated as early as 1846, added to its attractions a carousel and electric roller coaster in 1914 (see Connecticuthistory.org). Quassy, another lakeside picnic grove, first welcomed visitors in 1908 but didn’t turn itself into an amusement park until after World War II [see “Quassy Amusement Park” Summer 2006].

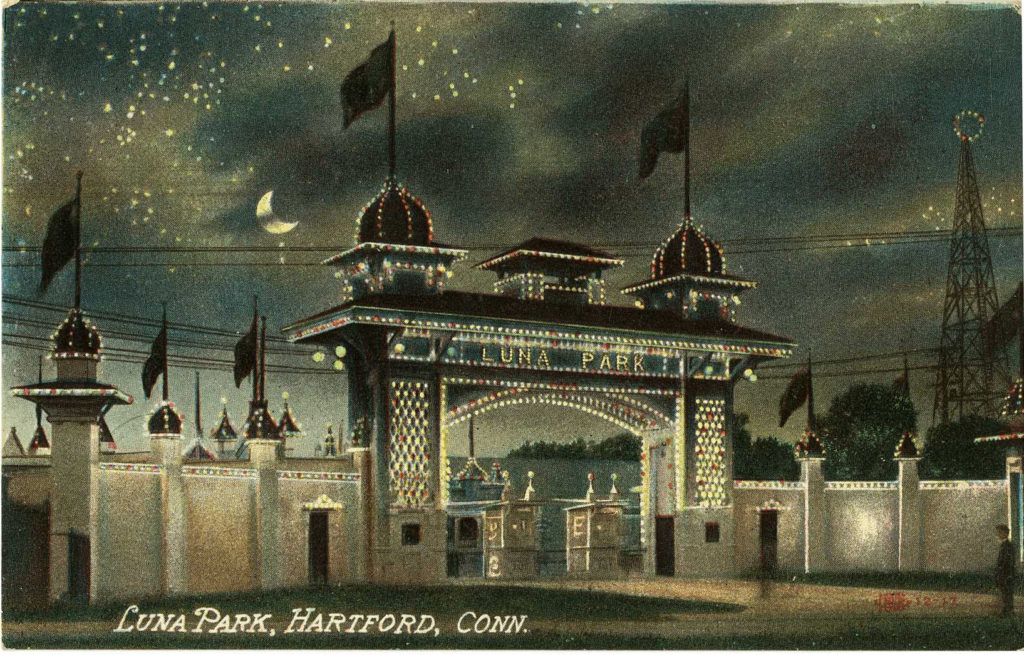

After the Luna Park groundbreaking in March 1906, hundreds of workmen took just three months to erect a garishly glamorous “White City” (inspired, as many other amusement parks were, by the White City at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago) topped with turrets, towers, and minarets. Festooned with 50,000 light bulbs, Luna Park aspired, said The Hartford Courant on March 14, “to outshine the Capitol dome.”

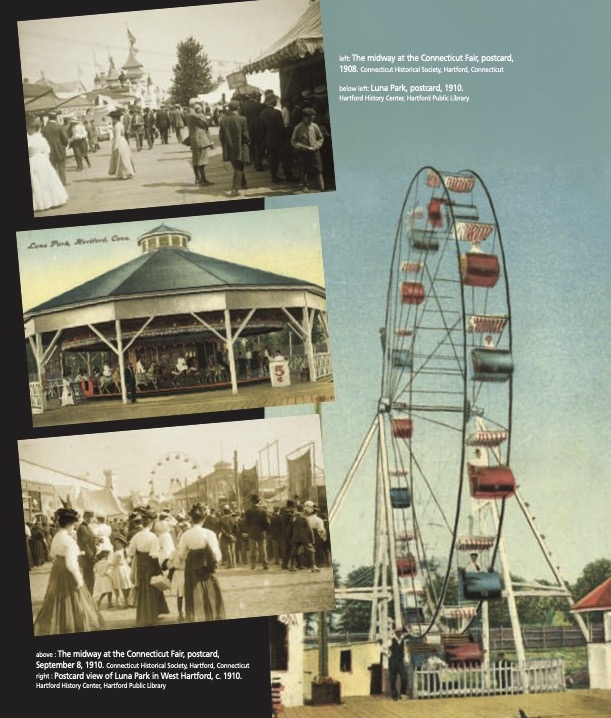

Luna’s star ride, according to The Courant (June 23, 1906), was the “scenic railway,” a “decided thriller” of a roller coaster with a mile of dips and “rush,” according to accounts published in The Courant between June and August 1906. Also popular were a Ferris wheel, a merry-go-round, an “Old Mill” tunnel of love, and a giant centrifuge called the “circle swing” that twirled daredevils high above the ground. Survivors could stroll a boardwalk jammed with food and game concessions. “San Francisco Disaster” recreated the great 1906 earthquake with films and a panorama. For the genteel there was a Japanese Tea Room and Ball Room, but most of the shows at Luna were carnival fare: “The Human Bomb” parachuting from a balloon, Mlle. Luba de Serema’s performing animals, Japanese acrobats, snake charmers, a Temple of Mirth, and cakewalk contests “by real colored people,” noted The Courant.

At the close of Luna’s first season the managers called the park “a financial success.” Sadly, it wasn’t so. Thousands of amusement-seekers visited daily, but Luna’s creditors and investors were not amused. By January 1909 The Courant was calling Luna a “lemon.”

As a business Luna Park suffered from two defects. First, from the start it was a reckless gamble. Though Luna mimicked the Coney Island amusement parks, Hartford lacked an ocean beachfront, and it was barely a 20th the size of New York. As if blinded by their own bright lights, Luna’s developers built too big for their market.

Second, Luna was too risqué, too sporty. After all, it sat adjacent to a racetrack. Young people, males in particular, loved Luna for its speed, sensualism, and exotic airs according to this author’s reading of several dozen articles in The Courant. But park proprietors struggled to attract the middle class and the middle-aged. For the park’s second season the owners added a skating rink, replaced the Ferris wheel with a theater, and planted flowers around the grounds.

In 1908 new management promised “clean, high-class amusement, catering especially to women and children.” In 1909 two Japanese entrepreneurs took over the park’s management, redecorated with lanterns, dressed waitresses in kimonos, and brought in a ladies’ orchestra. Nothing worked. Yashituro Takei and Tomosahura Tsurukai lost money just as had all their predecessors.

In September 1908 the Connecticut Fair Association leased both Luna Park and Charter Oak Park for a weeklong state fair. Luna’s attractions became sideshows to exhibits of livestock, produce, flowers, and crafts. The jamboree went off splendidly, its promoters boasted pointedly, because it offered strictly “clean” amusement.

The Fair Association decided to buy Luna for the sake of its grounds but made one last effort to open the park under its own name in the summer of 1910. A scrubbed and shrunken Luna featured music and movies a few evenings a week. But even this was too much for the West Hartford selectmen, who objected to showing movies on Sundays. Losing patrons, the park abruptly closed in mid-season.

The Luna eclipse proved to be permanent. In 1913 timbers from the dismantled scenic railway went to make cattle sheds for the Connecticut Fair.

Who killed Luna Park? Plungers who overinflated it—and prim Connecticans who popped the balloon. Financially and culturally, this venture proved just too adventurous.

Gene Leach is a professor of history and American Studies emeritus at Trinity College and a member of the Connecticut Explored editorial team.

Explore!

“Racing at Charter Oak Park,” Summer 2018