By Benjamin Foster Jr.

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Summer 2021

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

By 1940 African Americans constituted a growing segment of New Haven’s population. In response to manufacturers’ need for workers during World War II, the African American population of the city increased significantly.

To address the spiritual needs of these new city residents, in 1940 Bishop William J. Walls of the African American Methodist Episcopal Zion Church transferred the Reverend Richard A. G. Foster to New Haven’s Varick Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church, with the command “Bring them a bucket full of goodness and mercy,” as my brother, Rev. Dr. Lamont Foster, Sr., pastor of Rev. Richard Foster’s former church in North Carolina, told me.

Varick Memorial, located on Dixwell Avenue, was established in 1818, the second such congregation within the denomination. [See “Fortress of Faith, Agents of Change,” Summer 2011.] The denomination counts among its members icons Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and W.E.B. DuBois’s maternal family. Bishop Walls’s decision to bring Foster to New Haven was based on Foster’s ability to work with white ministers in the segregated South, his articulation of the plight of manual laborers, and his itinerant ministry experience, as his daughter Marianne Foster recalled in a conversation with me.

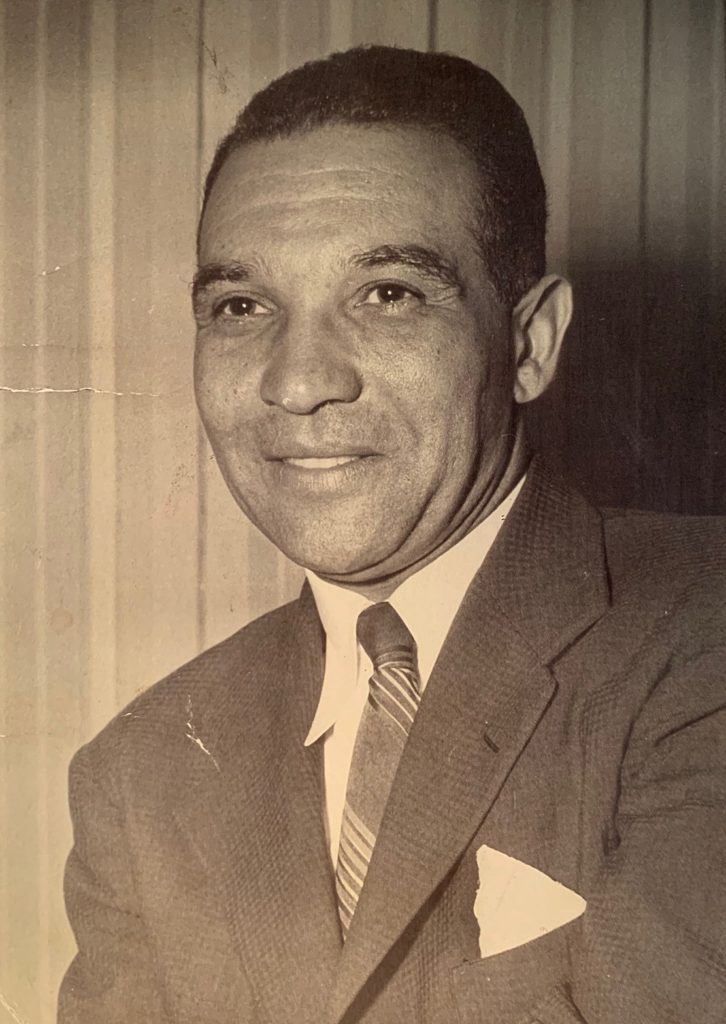

Rev. Foster came to New Haven from the St. John A.M.E. Zion Church in Wilson, North Carolina. That area’s economy was based on the production of tobacco. Many of his congregants in New Haven were from the North Carolina counties that Foster knew well. According to “The Preacher Who Batted .1400” (Negro Digest, Vol. III, No. 4, 1945), he would use the skills he gained as a scholar-athlete at Livingstone College and Hood Theological Seminary in Salisbury, North Carolina to guide his new flock and assist them in navigating the transition from rural to urban life. Handsome, affable, with a winning smile, and fiercely believing in the equality of all people, Foster took the pulpit of Varick with a membership of 40 active members.

Rev. Foster set about growing his church. Surveying the African American population’s status in New Haven, he regularly recited the mantra he had been taught in his segregated elementary school: “There is no such word as can’t, you try, and try again.”

Being the son of a preacher, Rev. Foster fully comprehended that text without context is pretext, a well-known concept in the African American preaching tradition. He immersed himself in the social and political life of New Haven. In 1943 Foster became the second African American elected to New Haven’s board of alders. A Republican, he served three terms representing the 19th ward, the area in which Varick is located, according to the April 1951 issue of Color magazine.

Using his considerable influence as an alderman, with a growing church and frequent interaction with politicians such as Mayor William C. Celentano, Republican State Chairman Clarence F. Baldwin, U. S. congressmen James T. Patterson and John Davis Lodge, and Connecticut Attorney General William L. Hadden, Foster helped domestic workers obtain better pay, as Color magazine reported. He secured more than 2,700 jobs for African Americans in the city’s factories and plants, which had not previously hired Black people. He was responsible for the city’s hiring the first African Americans as court clerks and in the police department.

Rev. Foster’s starting salary was $35 a week. He and his wife, Thelma Brooks Foster, raised five daughters, three born in New Haven, including Dr. Ellen Foster Randel, who recalled in conversation with me that the church parsonage was frequented by Bishop Walls, actor Paul Robeson, Reverend Fulton J. Sheen, Congressman Lodge and his wife Francesca Lodge, civil rights activist A. Phillip Randolph, Yale University professors Andrew Morehouse and Noni Gopal Dev Joardar, Livingston College President William Trent, boxer Jersey Joe Walcott, and others.

With seemingly boundless energy, according to Negro Digest, Rev. Foster found time to serve as secretary of the National Council of the A.M.E. Zion Church, secretary-treasurer of the Ministers’ Association of Greater New Haven (of which he was the only African American member), officer in the local NAACP chapter, and member of the city’s rent control commission. He mentored Levi Jackson, star running back and first African American captain of Yale’s football team.

After 12 years in New Haven, Rev. Foster was appointed to Greater Cooper A.M.E. Zion Church in Oakland, California, where he continued his path-breaking work. He gave the invocation at the 1964 Republican National Convention in San Francisco, as his daughter Rev. Lillian Foster-Hilliard recalled.

Foster died in Oakland in 1973. Much has occurred in New Haven since Foster’s time, but the contributions of this largely forgotten African American minister, politician, and humanist, who believed that “there was no such word as can’t,” are still being actualized.

Dr. Benjamin Foster Jr. is Richard A. G. Foster’s cousin. He is an adjunct faculty member at Central Connecticut State University and convener for the Institute for Cross-Cultural Awareness and Transformative Education. He led the effort to pass the 2019 law requiring that an elective course in African American studies be offered in Connecticut’s high schools.

Explore!

“Site Lines: The Black Church in Connecticut — Fortresses of Faith, Agents of Change,” Summer 2011

“Faith Congregational Church: 185 Years–Same People, Same Purpose,” Summer 2005

GO TO NEXT STORY

GO BACK TO SUMMER 2021 CONTENTS

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Sign up for our bi-weekly e-newsletter