By Carl J. Schneider and Dorothy Schneider

By Carl J. Schneider and Dorothy Schneider

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2010

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Eighty-odd years ago Connecticut’s people responded to the Great Depression in ways that wrought miracles—not economic ones, but miracles of compassion and community action.

In Seymour, Connecticut, the Depression struck hard, for the livelihood of its 7,000 people depended on the town’s wire, cable, brass castings, and fountain-pen mills. When the Depression descended—unanticipated, inexplicable, and unmanageable—bewildered laborers and owners alike watched the mills grind to a halt.

Then something stirred. In an era before federal aid, the town of Seymour adopted a plan, developed in nearby Waterbury, called Mutual Aid. The town called on its citizens who’d kept their jobs to pledge a percentage of their wages for six months and on employers to match those funds. Together their contributions supported part-time employment for the jobless. Workers were asked to pledge on a sliding scale: Those making up to $50 a month contributed 1 percent of those wages; those who made from $50 to $75 contributed one-and-a-half percent, those in the $75 to $100 range 2 percent, and those who earned more than $100 contributed 3 percent of their earnings.

Merchants donated goods such as clothing, fuel, and food. Private citizens let Mutual Aid employees cut wood on their lots. The mills loaned their trucks to transport goods and workers. The Chamber of Commerce instituted “eatless meetings” at which the customary meal was foregone and the money saved used to buy milk for children. Service clubs offered garden plots to the unemployed. Other organizations donated money raised from concerts, dances, and bake sales to the Mutual Aid organization, and Mutual Aid itself sponsored bridge tournaments, football games, and “picture shows.” Welcoming every idea and exploring all possibilities, Seymour improvised a program of work and assistance to benefit its neediest citizens during these dark times.

Reverend Edward A. Jones, c. 1930, pastor of the Seymour Congregational Church from 1924 to 1940. Courtesy of Seymour Congregational Church

In the long run the program was doomed. As more people lost their jobs, demands for social services soared and personal income plummeted, shrinking the revenue to support those services. By winter 1932, with the Connecticut unemployment rate approaching 27 percent, the system of relief was collapsing, as private agencies and towns alike ran out of money. In early 1933 the federal government came to the rescue with national employment programs. But for a critical period early in the Depression, the Mutual Aid fed the hungry, warmed the cold, and sparked hope in the desperate.

Its memory survives in the recollections of Edward A. Jones. In 1924, some five years before the Depression hit, Jones, who was born and bred on a Missouri subsistence farm, resigned his jobs as a circuit-riding Methodist preacher and school superintendent, packed up his wife and daughter (now Dorothy Schneider, a co-author of this article), and headed his Model T Ford automobile east, riding high on his hope to earn a Yale divinity degree. In New Haven he found a furnished apartment, where, his wife sobbed one miserable night, “The sheets are so thin and the cups are so thick.”

By 1929, Jones was well established as the pastor of the Seymour Congregational Church, had completed most of his work for his divinity degree, and had sizably increased the church membership. He and his church were prospering along with the community. Then the stock market crashed.

I’ll say this for the people in Seymour. They got up on their two feet and tried to help themselves, every way they could.

Seymour was a little manufacturing town. Now I had come from a farming area where we made nothing. Everything grew. In this community they didn’t grow anything, but they made everything that you could imagine, from a 600-pound metal ingot to wire no bigger than a hair. They made an intercontinental cable to go under the Pacific Ocean [undersea intercontinental cable]that took 42 flat cars to haul. They made blanks for silver-plating, stamping out the blanks and sending them away to be plated. They made sheet copper and sheet brass. The Waterman Pen Company didn’t employ as many, but it was a big, prosperous company.

Seymour had a diverse population. During World War I, the government had drafted so many men that the factories couldn’t operate at full-scale any more, so the manufacturers agreed with the government that they would finance a shipload of men from Europe who wanted to come to this country, a whole shipload, and a representative would put so many hundred men from the ship on the train to Waterbury, and let off so many at Ansonia, so many in Derby, so many in Shelton. They didn’t have names for these men, just counted them off, then housed them in the factory attics on folding cots.

After the war, the men began to send for their wives, their sweethearts, and first thing you know we had a new family of immigrants. The cheapest houses available were some of the best houses, but the old families had run out at the heel and let the property decline until it brought hardly anything. These Polish men bought those places on credit and after the day’s work anywhere from four to a dozen of those men would work on one house until ten or ten-thirty at night. When they got one fixed, they would work on another fellow’s house. At the end the best-kept houses in town were those they fixed up for themselves.

By the time I went to Seymour, there were a great many Polish and Russian immigrants. Many Middle Europeans, Baltic peoples, Italians, Greeks. Something of a melting pot. But the people in my church were not generally recent immigrants, not the ones who worked in the mills so much as the merchants and management, the old-line Protestant families, who were relatively prosperous and well established.

Then the Depression hit. Just as big a surprise to people in Seymour as to the Wall Streeters who jumped out the windows. To begin with, nobody knew what we could do about it. It looked like we were powerless. A considerable number of families were hard-pressed to have enough food and yet they were proud, loath to ask for assistance—used to taking care of themselves.

I’ll say this for management, too: They didn’t just fire people. Instead they told them they would call them the first opportunity they had, and they lived up to that promise one thousand percent. They hired men to wash windows just to give a man a day and a half of work a month. People said that if they washed the factory windows much more, there wouldn’t be any glass left in ‘em.

And the thoughtful people of the community talked incessantly. There must be something that we could do to ameliorate the conditions.

Tingue Silk Mills and Waterman Fountain Pen Factory. Seymour entered the Depression as a factory town that had drawn immigrantsduringWWItoworkinthemills. Postcardc.1920. Museum of Connecticut History

The Evening Sentinel, the local newspaper, revealed the urgency of the situation. In an undated article, it reported that the funds of the Public Health Nurses and the American Red Cross were depleted. The town was caught in a double bind: It was difficult to collect taxes even as expenditures to provide for the poor ran double the budgeted amount.

On October 23, 1931, a community-wide meeting established a committee of church representatives, manufacturers, merchants, nurses, and the board of selectmen. Jones, a committee member, recalled:

There were eleven or twelve on the committee. That committee was as democratic as I know how a committee could be. If we had had any other resource in the community, we would have invited them, [and]been thankful to discover another resource.

The selectmen would try most any recommendation that made sense, because the situation was so desperate. Most people didn’t know what in the world to do, but if someone else suggested something, it seemed unsporty to down it without trying it.

As The Evening Sentinel reported on January 21, 1932: “. . . hardly a day . . . but introduces some project, which just as soon as it is mentioned is looked into. In almost every case reported it is found that the project is well worth while, and a record of all of these are kept so that in the mapping out of work for those who are employed by the Mutual Aid there will be no lack of places. . . .”

As Jones remembered,

We had to plan and devise everything from grass roots. Pretty soon the committee came up with the idea that we ask everyone who had a job to contribute three percent of his weekly wage. From that we hired people to do things that needed to be done—for instance, repaint school buildings. They even repainted a lot of parish halls and a few churches. There was a crying need for sidewalks, and the help-out crew leader recommended that the town advertise that anybody that wanted a sidewalk by his property could contribute a small portion of the cost of materials, and the town and this helping fund combined would put the sidewalk in for almost nothing.

The Seymour Congregational Church, where Mutual Aid held free events for the community during the Depression.

Tercentenary Pictorial and History of the Lower Naugatuck Valley, Leo Thomas Molloy, Press of the Emerson Bros., 1935.

The Mutual Aid also employed men to shovel snow, improve the library, install curbs and gutters, grade banks and repair fences, and work on roads, cemeteries, and parks. It paid for the manufacture at a local mill of the town’s first street signs and the labor to install them. Householders were asked to offer small jobs on their property. “No money is given those seeking help,” the Sentinel reported on November 10, 1931, “but orders are given for what is needed in the way of food, clothing, fuel and other things, while at the same time the . . . organization will . . . try and secure some work for the applicant.”

Jones summed up the nature and impact of Mutual Aid, saying

I never heard anyone complain that the committee was playing favorites, nor a businessman complain that his business was hurt. For instance, instead of sending a load of coal to a family, we sent a load of wood cut by men we had hired to cut the stuff, bring it into town, pile it up in the town’s lot. Now that robbed coal dealers of good cash, but I never heard a coal dealer complain.

The committee did not at first think about recreation but soon we felt need of getting groups of people together where they could all enjoy the same thing. It was a very sad community when we started, with nothing for people to do all day. People who’d been laid off work just wandered around. It was just worry, worry, worry, you know. So we conceived the idea of putting on some free entertainment, by drafting resources from the Naugatuck Valley. I said, “I don’t know these people individually, but up and down this valley there are men and women capable of entertaining an audience.”

A Pole on the committee said, “I know a bunch of people from Naugatuck and Waterbury and on up north. They’ve been meeting every once in a while for some Polish dances. Why don’t we get them down here and put on a Polish dance?” They were unemployed too, and the young fellow told us, “They’ve got plenty of time to practice! They’ll go anywhere without a fee.” Our new parish hall would seat more people than any other hall in town. I said, “Now there won’t be any charges. The church will just absorb the janitorial bills and all of that.” That night the place was jam-packed full early on, and they just kept pouring in. There was a hallway about twelve by twenty leading to the main entrance, and that was jammed from one end to the other and out to the street. It was a half-basement, so they were around all the windows looking in, and those at the window would report to people behind them what was taking place. The police said at least 850 came out for that show.

The dancers had authentic national costumes, and they knew how to do those dances that were their national inheritance. They just danced their feet and legs off until after eleven o’clock. We put on other programs after that.

I can’t recall of any opposition. As I look back, I think it’s amazing that no one objected to employing people to redecorate the church. That obviously was a violation of the separation of church and state, just as plain as ABCs, but no one wanted to even whisper about it, because if you took that work away, there was no other place that you could put them to work—just a case of do this or do worse.

When we first began a few people we employed acted smart aleck. I remember one fellow on a cold morning took a new axe and hit it broadside against a stone and broke it. The crew manager told him, “Now I’m gonna forget that this happened. But if you ever do anything like this again, you’ll be on your own, and your family will have to look after itself. Well of course he didn’t break any more axes. But there was very little of that.

No, most of the time everybody cooperated. The idea got abroad that community management wanted to help the unemployed. We sold that idea.

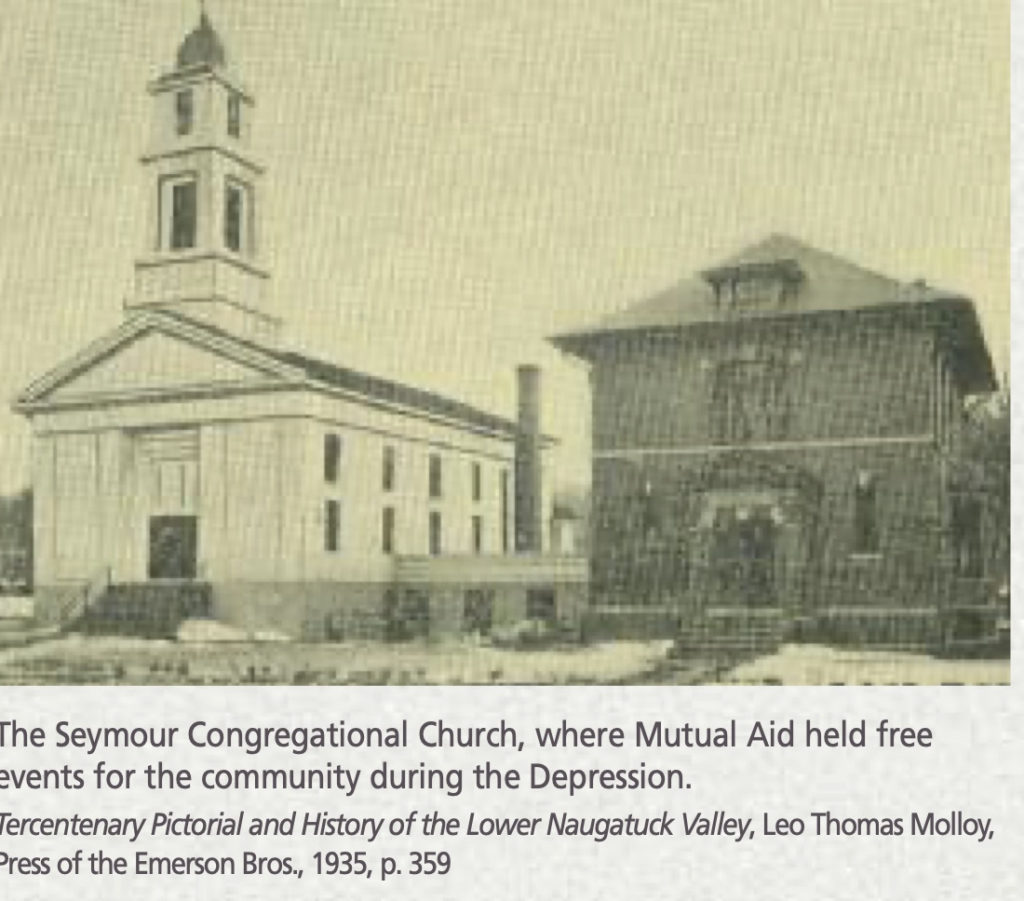

One thing amused me. The wealthiest person in town and the vice-chair of the committee was Mrs. Matthies. Once someone suggested that maybe we shouldn’t let the women whose families we were supplying with weekly food-baskets choose their own foods. Mrs. Matthies said, “Stuff and nonsense! I go shopping right along with these women, and they get a lot more for their money than I get for mine!”

The trouble was, we never figured on the Depression lasting so long. More people lost their jobs and needed help, and of course their contributions to Mutual Aid stopped. We had to stop collecting funds from them in June of 1932, but we did ask that if people couldn’t give cash they try to give work to somebody for one day. In August the money just petered out, and we had to suspend operations. We tried again in the fall, but it was uphill work.

We’d made a real difference though. For the time Mutual Aid was in operation, the town had a budget of $15,000 for its poor. It actually had to spend $50,000 just to keep people from starving or freezing, and Mutual Aid came up with $20,000 of that—in Depression dollars. We did a lot to help the unemployed. And we turned our town into a real community.

top right: Mrs. Katharine Matthies, shown here c. 1935, was “the wealthiest person in town” and vice-chair of the Mutual Aid committee. Seymour Historical Society. Bottom: The Seymour Company, postcard c. 1910 Museum of Connecticut History

Carl J. and Dorothy Schneider, after careers as college professors and administrators, in their retirement began writing about American history. Their most recent books include Slavery in America: An Eyewitness History, and First Ladies: A Biographical Dictionary (3rd edition, 2010.)

Explore!

Read more stories about how Connecticans have dealt with hard times in the Spring 2010 issue.