The first independent school of law in America was founded in Litchfield, Connecticut, by Long Island native Tapping Reeve. Having completed his education at Princeton in 1774, Reeve went to Hartford to read law with Jesse Root, a respected attorney who later served as chief justice of the Connecticut Supreme Court. In 1772 Reeve married Sally Burr, a pupil he had tutored, along with her brother Aaron (yes, that Aaron Burr), while at Princeton.

The Reeves had a house built in Litchfield in 1774, and Reeve welcomed his first student–again, Aaron Burr–that same year. He spent the years of the Revolutionary War (1775-1781) as a recruiter for the Continental Army; when the war ended, Reeve began his law practice in earnest and started teaching law. His earlier students may have learned in the traditional manner of reading law in Reeve’s home office, but by 1784, he had created a 14-month course of lectures on legal topics based on Sir William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, published by Clarendon Press in Oxford, England between 1765 and 1770.

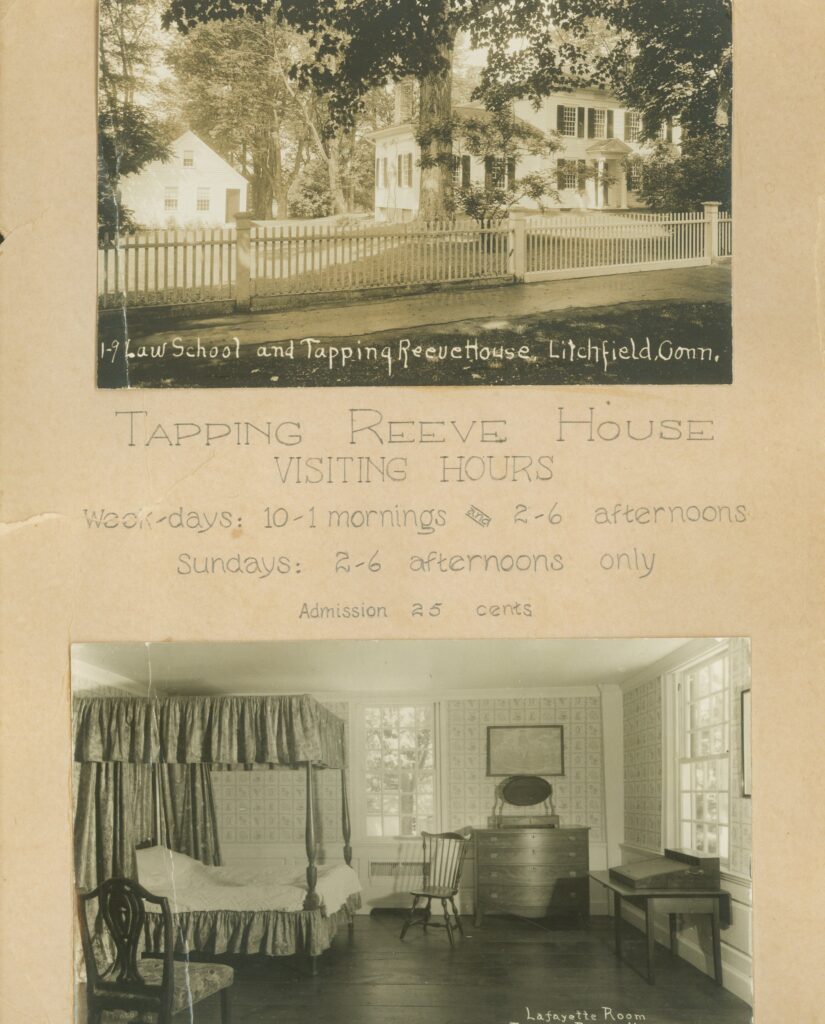

In 1784 Reeve built a separate structure to accommodate an increasing number of students. Complete enrollment records for the school do not exist, but there are only seven students documented to have studied with Reeve between 1774 and 1784, the same number documented as having attended between 1784 and 1786.

Reeve remained the sole proprietor of the Law School until he was elected to the state Supreme Court. He then hired former student James Gould, who lived on North Street, to give lectures. Gould gave his lectures in a second small structure he had constructed next to his own home. Some students participated in moot court and mock trial, and they were encouraged to attend cases at the county courthouse. Student notebooks from this era contain lectures from both instructors. The peak of enrollment was reached in 1813, when 55 students attended.

It is likely that Reeve chose Litchfield for several reasons. Its designation as the county seat meant that an active courthouse would provide him with work–and potentially students. Litchfield was easy to get to from Boston, New York, and Albany. Finally, it was fortunate for him that his neighbor on North Street, Sarah Pierce, had opened the Litchfield Female Academy in 1792, offering both academic and ornamental courses to young women who traveled from around the new nation to attend. Pierce was a proponent of what we now call Republican Motherhood, which held that women were responsible for the early intellectual and moral training of their children and that their ability to educate them was crucial to the survival of the country. The location of the two schools in the same town allowed siblings to travel together, and it provided both young women and young men with the opportunity to make good matches. More than 100 student couples were formed in Litchfield during the lifespan of the schools. State Historian Emeritus Walter Woodward has called it “the nation’s first college party town.”

Reeve’s students would go to prominent positions in the new United States government: graduates included two vice presidents, three U.S. Supreme Court justices, six members of presidential cabinets, 28 senators, and more than 100 members of Congress. Fifteen were governors of states or territories, and many others were elected to local and state positions. Those who studied law in Litchfield were later responsible for writing, interpreting, and enforcing the laws of the new nation. Alumni settled in 34 states and three territories. Some, like educator Horace Mann and artist George Catlin, became prominent in other fields. The Litchfield Law School shaped future legal education in the United States. Reeve distinguished the study of the law as based upon general principles and methods, and upon a national level, not as they pertained to specific states. The school established the formal study of law as graduate education, distinct from an undergraduate curriculum. However, the more practical or clinical aspects of learning the law were left to further apprenticeship.

For the Litchfield Historical Society, preserving and interpreting the story of Reeve was no small feat. Reeve’s only son, Aaron Burr Reeve, predeceased him. His grandson, Tapping Burr Reeve, died at age 20 in 1829. Reeve’s property was inherited by his widow, second wife Elizabeth Thompson Reeve. After she died in 1842, the house was owned by Amelia Ogden, a cousin of Reeve’s first wife, who had lived with the Reeves as Elizabeth’s companion. Various members of the Woodruff family held the property until the death of Lewis B. Woodruff in 1925. His grandfather, also named Lewis B. Woodruff, attended the law school in 1830. Woodruff bequeathed his estate Yale University. The Litchfield Historical Society bought the house in 1929.

The law school building had its own path to preservation. According to Dwight C. Kilbourn’s 1909 book The Bench and Bar of Litchfield County, Connecticut, 1709-1909, local poet and publisher Henry Ward removed it to a plot of land on West Hill and converted it into a small house in 1846. Ward later sold the house to Mrs. Mary Daniels and her son, music teacher and composer Charles F. Daniels of New York, who summered there.

Kilbourn, himself a lawyer, took it upon himself to preserve the building. He chaired a committee appointed by the Litchfield County Bar and, in 1907, went before the Connecticut General Assembly to propose the state buy and maintain the building. This proposal was rejected. According to Kilbourn, the executor was obliged to sell the property at auction. Kilbourn purchased the property for $2,700. He relocated the building to the extreme west end of the lot and restored it “inside and out.”

Interest in preserving the law school building never waned, but the structure was relocated four additional times. The records of the Litchfield Historical Society include an August 12, 1910 “Report of the Committee on Acceptance of Judge Reeve’s Law School.” The committee examined and measured the building and decided to place it on the southeast corner of the grounds of the Noyes Memorial Building, where its collections were housed. This was the law school building’s third move. Although the committee noted that the law school also needed interior restoration, the historical society’s financial situation prevented it from making funds available for the purpose. The society moved the building again in 1922, changing the orientation to face South Street and moving it closer to the street.

Interest in preserving the law school building never waned, but the structure was relocated four additional times. The records of the Litchfield Historical Society include an August 12, 1910 “Report of the Committee on Acceptance of Judge Reeve’s Law School.” The committee examined and measured the building and decided to place it on the southeast corner of the grounds of the Noyes Memorial Building, where its collections were housed. This was the law school building’s third move. Although the committee noted that the law school also needed interior restoration, the historical society’s financial situation prevented it from making funds available for the purpose. The society moved the building again in 1922, changing the orientation to face South Street and moving it closer to the street.

The Litchfield Historical Society rented the law school building to tenants as a source of revenue during the early 20th century. Arthur E. Bostwick, a Litchfield native who went on to a career as a prominent librarian and president of the American Library Association, published a pamphlet titled The Old Law School Building in Litchfield Conn. in 1928. In meticulous detail, Bostwick described the location and uses of this building from its acquisition in 1910 to the date of publication. Miss Margaret Sanford operated a shop there, followed by the Woman’s Shop of Litchfield, run by Ella Coit, who had paid a contractor to install a chimney in the law school in 1926. Her lease was renewed for two years in 1928, shortly before the building suffered a chimney fire. Though her lease was not terminated, she was provided with an electric heater.

During the same era The Village Improvement Society held regular fètes, fairs, and lectures to raise funds to “restore” Litchfield to colonial style, removing vestiges of other architectural styles. In 1929 the 1872 Gothic Congregational Church was razed to replace it with its predecessor, an 1829 structure. In the same year the Litchfield Historical Society voted to purchase the Tapping Reeve House from Yale for $21,000. The Colonial Revival, with its emphasis on Georgian and federal architecture, presented the perfect opportunity to preserve and restore structures associated with the Litchfield Law School and present its history to the public.

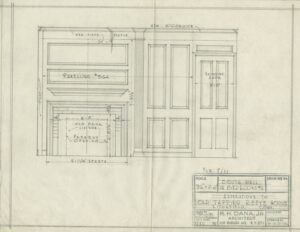

The purchase of the Tapping Reeve House coincided with the stock market crash preceding the Great Depression. Though the committee obtained letters of support from individuals as prominent as former President and then Chief Justice of the U.S. Supreme Court William Howard Taft and Connecticut Governor John H. Trumbull, the fundraising process was slow. Still, the society raised money to hire noted colonial revival architect Richard Henry Dana to restore the house, relocate the law school building to the South Street property, and construct a fireproof vault attached to the school for storing related collections.

The society had no professional staff at the time, but dedicated volunteers including Colonel Samuel Fisher sought support from those who practiced law. Board minutes from October 6, 1930 note, “Col. Fisher reported the receipt of a letter from Felix Frankfurter of Harvard College, expressing his great interest in the restoration of the Law School and saying he had a good deal of material he would be glad to donate later.”

Fisher was instrumental in educating supporters. For instance, Taft’s first letter, in August 1929, acknowledged, “I should be glad to join in a movement to restore in any proper way a Litchfield Law School Memorial. I know very little about it… If you will give me a few more details as to where I can make some inquiries, I shall prosecute them.” A few months later, in October, Taft sent a two-page document expressing why he was making a contribution to the cause. He said, “I have voluntarily made a small contribution to this purpose believing that there should be established here a shrine or memorial of the beginnings of the Law under the Constitutions of the United States and the Several States.”

Fundraising efforts were successful enough for the society to hire Dana and relocate the law school a fifth time, to the South Street property. Despite having evidence and eyewitness accounts of its original location, the committee chose the location according to aesthetics. According to minutes from an October 20, 1930 meeting of the Tapping Reeve House Restoration Committee, “A frame-work of the exact size of the Law School was moved about various locations as an aid in judging of its appearance in relation to the house. It was finally agreed that a location diagonally south-west of the house and near the copper beech tree was best.…”

Volunteers also worked to furnish the house. Some furnishings that were in the house at the time of purchase were kept, while others were donated or leant. The board voted to send celebratory notes of gratitude, singling out Francis Patrick Garvan and his wife Mabel Brady Garvan for making the “Tapping Reeve house a fitting memorial to the distinguished founder of the Litchfield Law School, and their very helpful and practical assistance in presenting the Society with the paneled room from the Gideon King House.” The Mabel Grady Garvan foundation provided “a generous loan of suitable furniture and furnishings from the Mabel Brady Garvan Foundation for exhibition in the house when completed…” The School of Fine Arts at Yale University received “the appreciative thanks of the Committee for the cooperation afforded it in the restoration of the Tapping Reeve house.”

The committee worked tirelessly to promote and raise money. Articles like “Let’s Go Places” in Connecticut Motorist encouraged visitation to the site. Others took pride in the preservation, like Princeton’s Alumni Weekly, which published “The First Law School in America: Some Facts About an Erstwhile Institution Founded by a Princeton Man” in 1930. The New York Times and the New York Herald Tribune also ran stories. Colonel Fisher continued his years-long efforts to document the students and publish a catalogue. Boxes of his correspondence with various state historical societies, libraries, and genealogists demonstrate his commitment to compiling an accurate list of those who attended the Litchfield Law School.

As part of a town initiative to preserve historic sites and establish a historic district, the Tapping Reeve House received National Landmark Designation in 1966. By the 1970s it became clear that digging a basement for and attaching a vault to the law school building had created hazardous environmental conditions that were exacerbated by a decision not to heat the building. The law school was closed to visitors in 1974 for emergency structural repairs. The historical society hired local architect Thomas C. Babbitt, the grandson of Colonel Samuel Fisher, to manage the project.

Between 1974 and 1975 the society’s director, Lockett Ford Ballard Jr., worked with a committee to determine the original location of the law school and whether it had had a foundation. The committee also addressed the interior restorations that had been put off in 1911. Partitions installed when the law school became a house, including a hearth and chimney, were to be removed. Using an 1814 map drawn by law school student Sydney E. Morse, minutes from meetings with Richard Henry Dana Jr., and an amateur archaeological dig, the committee found that the original location of the law school overlapped with a more recent community treasure: the Howe Garden. In 1935 Anne Wilson Howe, then president of the Litchfield Garden Club, donated and installed the colonial-style “Howe Garden” in front of the law school building in memory of her husband Ernest Howe, a geologist who had surveyed the Panama Canal zone.

Between 1974 and 1975 the society’s director, Lockett Ford Ballard Jr., worked with a committee to determine the original location of the law school and whether it had had a foundation. The committee also addressed the interior restorations that had been put off in 1911. Partitions installed when the law school became a house, including a hearth and chimney, were to be removed. Using an 1814 map drawn by law school student Sydney E. Morse, minutes from meetings with Richard Henry Dana Jr., and an amateur archaeological dig, the committee found that the original location of the law school overlapped with a more recent community treasure: the Howe Garden. In 1935 Anne Wilson Howe, then president of the Litchfield Garden Club, donated and installed the colonial-style “Howe Garden” in front of the law school building in memory of her husband Ernest Howe, a geologist who had surveyed the Panama Canal zone.

The society applied for and was awarded a $5,000 grant through the State Historic Preservation Office to restore the Litchfield Law School to its original site and make structural repairs, including the replacement of rotting beams and removal of the vault. A special committee was appointed to renovate the Howe Memorial Garden, which was reimagined along the walkways between the house and the law school building.

The law school building was moved for the sixth time to its present location and turned 180 degrees to restore it closely to its original position. Yet interpretation of the tiny building that legal historian and Yale professor John Langbein often told students on annual field trips “was once the largest law school in the Anglo-American world” was limited to a photo gallery of former students on the wall. The historical society made attempts over the years to reinterpret the site to focus more on the Litchfield Law School’s place in legal history, but none came to fruition, and the Tapping Reeve House remained just one more example of a historic house museum.

The law school building was moved for the sixth time to its present location and turned 180 degrees to restore it closely to its original position. Yet interpretation of the tiny building that legal historian and Yale professor John Langbein often told students on annual field trips “was once the largest law school in the Anglo-American world” was limited to a photo gallery of former students on the wall. The historical society made attempts over the years to reinterpret the site to focus more on the Litchfield Law School’s place in legal history, but none came to fruition, and the Tapping Reeve House remained just one more example of a historic house museum.

In 1987 the society hired Catherine K. Fields as its director. A major grant-funded exhibition telling the story of the Litchfield Female Academy had just opened when Fields broached the subject of reinterpreting the Reeve site with the board. Recognizing that it could best be used to tell the story of Tapping Reeve and his students, the society embarked on a multi-year project to renovate the buildings and reinterpret the sites. The project was funded by a capital campaign and by grants from Connecticut Humanities and local foundations. The society hired Historic New England to undertake a historic structures report, which revealed that little evidence of what the buildings were like during Reeve’s time existed. As any attempt to interpret the site as a historic house museum would be purely speculative, the society instead focused on an exhibition to tell the story of Reeve and his students.

In 1987 the society hired Catherine K. Fields as its director. A major grant-funded exhibition telling the story of the Litchfield Female Academy had just opened when Fields broached the subject of reinterpreting the Reeve site with the board. Recognizing that it could best be used to tell the story of Tapping Reeve and his students, the society embarked on a multi-year project to renovate the buildings and reinterpret the sites. The project was funded by a capital campaign and by grants from Connecticut Humanities and local foundations. The society hired Historic New England to undertake a historic structures report, which revealed that little evidence of what the buildings were like during Reeve’s time existed. As any attempt to interpret the site as a historic house museum would be purely speculative, the society instead focused on an exhibition to tell the story of Reeve and his students.

Acknowledging that the influence of the law school extended well beyond Litchfield, the society felt its interpretation should, too. In 2009 a federal grant from the Institute for Museum and Library Services enabled the development of an online database, The Ledger, which provides online access to the students’ stories, demonstrates the connections between them, and provides links to related artifacts and documents. In 2016 the staff and board began a fundraising campaign and project to create an outdoor community space, the Tapping Reeve Meadow. This proved to be a valuable addition during the pandemic, providing a safe space for community gatherings, outdoor exhibitions, and public programs. The pandemic also inspired the society to create a virtual tour of the Tapping Reeve House, accessible at litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org.

As Arthur E. Bostwick noted, “Judge Reeve trained his pupils to be great lawyers and statesmen in a modest structure whose use for that purpose would now be unthinkable. But he could have trained them no better in a marble palace.”

Explore!

Tapping Reeve House and Litchfield Law School

7 South Street, Litchfield

860-567-4501

Wednesday-Friday, 11 a.m. – 5 p.m., April-November or online at litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org/museums/tapping-reeve-house-and-law-school/

The Ledger

ledger.litchfieldhistoricalsociety.org/ledger/

“The Influence of the Litchfield Law School,” Connecticut Explored, Fall 201