By Evan E. Brown

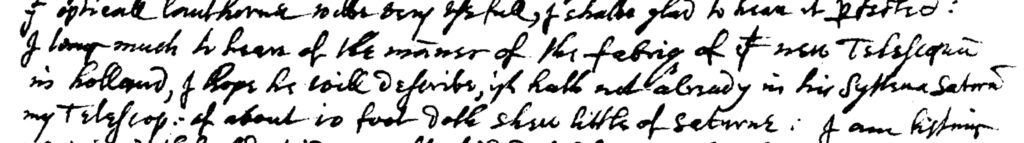

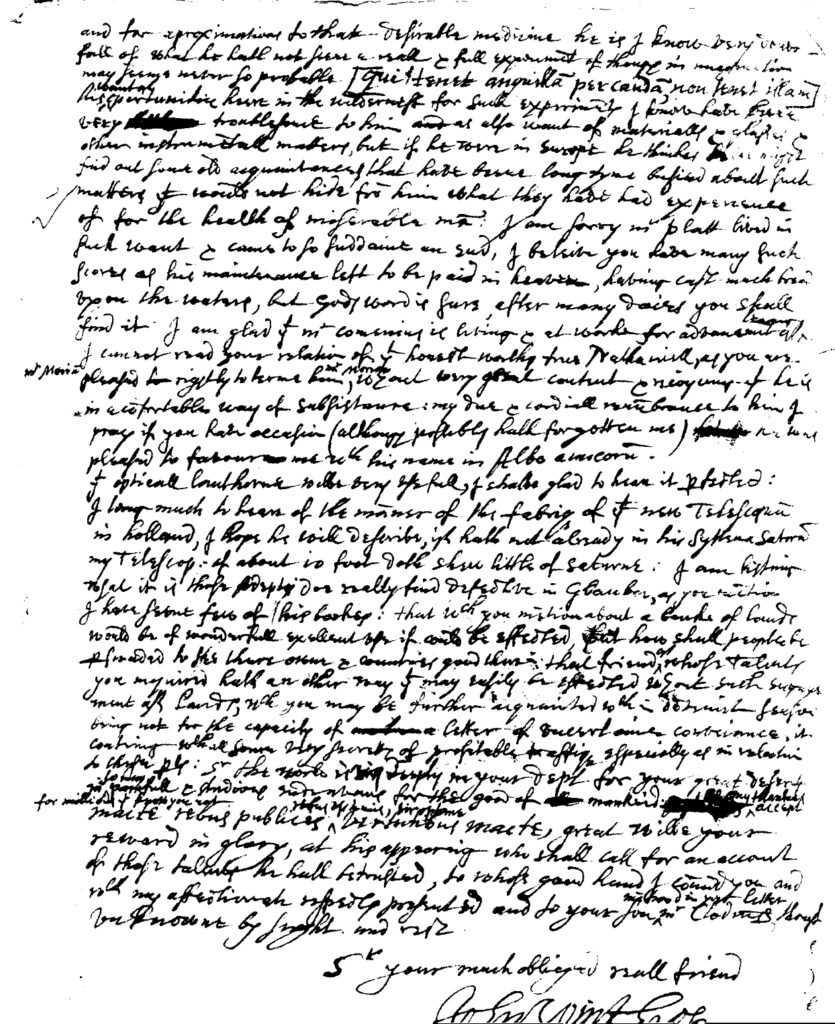

No one knows precisely when or where it happened. Still, sometime between August and October 1660, near Hartford, John Winthrop Jr., Connecticut’s governor and a natural philosopher, became the first person in America to look through a telescope. In an October 25, 1660, letter to educational philosopher Samuel Hartlib, published in Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 72 (October 1957–December 1960), Winthrop wrote: “I long much to hear of . . . that new Telescopium in Holland. My Telescope of about 10-foot doth show little of Saturn.”

Winthrop’s humble report can be magnified to offer insight into the beliefs of New England Puritans, which included both acceptance of the existence of witches and interest in the latest scientific discoveries. Although wealthy Puritans valued formal education—John Winthrop Jr. attended Trinity College in Dublin and studied law in London—the flawed perception of a Puritan society ruled by “bigots and radically devout people” refuses to die, according to Yaroslav Sobolievsky in “The Phenomenon of Cosmological Ideas in Early American Puritan Philosophy,” Philosophy and Cosmology 30 (2023).

Like Trinity College, the University of Cambridge was a hub of English Puritan intellectualism. As Perez Zagorin demonstrates in Francis Bacon (Princeton University Press, 2020), Cambridge produced one of the progenitors of the Scientific Revolution, who was nevertheless a man of “deep paradoxes.” Bacon was a natural philosopher who transformed the scientific method, emphasizing empiricism and “a new logic of inquiry.” Another Cambridge scholar was Winthrop’s younger brother, Forth, who declared to John Jr. in a 1628 letter now in the collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society, “There amid the divine abodes of philosophers, I have decided to search out and unravel the secrets which Nature still holds in her silent bosom.” It was an aim the brothers shared.

Letter, John Winthrop To Samuel Hartlib, 25 October 1660, Ref: 32/1/8A-9B, Greengrass, M., Leslie, M. and Hannon, M. (2013). The Hartlib Papers. Published by The Digital Humanities Institute, University of Sheffield

In Prospero’s America (University of North Carolina Press, 2010), Walter W. Woodward, former Connecticut state historian, writes, “Like many natural philosophers of his age, Winthrop believed he lived in a time of special theological purpose . . . in which God had elected again to reveal total knowledge of the natural and supernatural worlds.” Alchemists like Winthrop, influenced by the Bible, Platonism, and burgeoning empiricism, sought to transmute substances and find a universal cure for all ailments. Their aims would be achieved, they believed, “through a process of research and discovery that would foreshadow Christ’s Second Coming.”

Winthrop’s October 1660 letter to Hartlib exemplified such belief. Before discussing telescopes, Winthrop mused, “The approaching times of the manifestation of natural truths is very probable & were very desirable, & this age hath in some measure tasted thereof.” He believed science was part of God’s plan but understood that discoveries could come with a price. “God hideth from the unworthy, vain, sinful world many excellent things, which he knoweth they are very apt to abuse. . . . Rich men commonly reap the benefits of inventions to make them more rich, & the poor yet more miserable & uncomfortable.”

Alchemists’ goal then was to know the mind of God for the betterment of humanity and to keep that knowledge in “responsible” hands, which naturally included those like Winthrop’s. Alchemists formed a sort of secret society, writing to one another in code. They also engaged in public projects involving metallurgy and medicine. Winthrop built New England’s first ironworks in Massachusetts, established New London as a haven for industry, and, as a physician, treated numerous patients for decades. That ethos also compelled him to experiment with telescopes.

In 1664, John Winthrop Jr. returned from a voyage to England with three treasures: a royal charter establishing the legal foundation of the Connecticut Colony, membership in the Royal Society, and a new three-and-a-half-foot telescope. He used that telescope near his Hartford home, as he wrote to Benjamin Worsley in 1670, to observe “the planets, especially Jupiter” and “the glorious Constellation of Orion,” as cited by Ronald Sterne Wilkinson in “John Winthrop Jr. and America’s First Telescopes,” The New England Quarterly 35, no. 4 (1962).

Toward the end of his life, Winthrop turned his sights toward furthering scientific advancement in New England for future generations. In 1672, with Yale decades away from its founding, he donated his telescope to Harvard—the first scientific instrument the institution ever owned. Using his telescope, students made observations cited in Isaac Newton’s Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica and Increase Mather’s Kometographia and helped astronomy become, according to Samuel Eliot Morison in Harvard College in the Seventeenth Century 1 (Harvard University Press, 1936), “the only subject in which the College made some contribution toward the advancement of learning” during that era. In the 18th century, Winthrop’s great-grandnephew, also named John, became a prominent American astronomer in the department John Winthrop Jr. helped establish.

By that time, Winthrop’s donated telescope had disappeared from the record. As for his first telescope, it was never mentioned after the Hartlib letter. Yet its importance persists. On a clear night in 1660, John Winthrop Jr. stood on a spot in Connecticut, turned his eye and intellect skyward through a homemade telescope—America’s first—and helped establish a scientific legacy that endures to this day.

Evan E. Brown is a Master of Theological Studies student at Boston College. A lifelong student of history and an amateur anthropologist, he works in public education and entertainment.

Learn More!

“America’s First Planetarium–Who Knew?” connecticuthistory.org/americas-first-planetarium-who-knew