By Arianna Basche and Mitch Curry

A monument located in Greenwich marking Bound # 150 of the New York-Connecticut state line. This photo was taken circa 1955-1958 by a photographer contracted by the State of Connecticut. photo: Connecticut State Library

To be a good land surveyor, you need the investigative skills of a historian. Surveyors search through archives at municipal land record vaults, reading through deeds and examining the work of past surveyors. By parsing the clues left behind and conducting original work in the field, a surveyor creates an accurate map of existing property lines. And, like the surveyors of years past, they can file their map with the local municipal clerk to be used by future generations.

The same monument, photographed in 2023. It’s still standing 113 years later, but it needs to be reset. The center of the top of an upright monument represents the discrete point on the boundary line. Because this monument is leaning, it is difficult to determine the original location of this point. photo: Arianna Basche and Mitch Curry.

In addition to creating a map of a property, surveyors often set “monuments,” or physical markers of particular points on a property boundary line. Monuments created by surveyors are “artificial,” but boundaries can also be marked by “natural” monuments, such as rivers or specific trees. Boundary points are laid out in language in deeds, conveyances, and other property agreements. Whether an agreement is between states, towns, or property owners, written documents are only useful if the information they contain can be externalized. When it comes time to locate a property’s boundaries in the real-world landscape, authentic, distinguishable monuments can be of great help. However, because these objects exist in the physical realm, they risk being moved, destroyed, or lost. It is the surveyor’s job to re-establish the original boundary set forth in the land agreement, resetting any damaged or destroyed monuments they discover along the way.

The boundary between Connecticut and New York has been a much-disputed line since Connecticut received its royal charter in 1662. These disputes have led to multiple re-surveys, generating a massive amount of documentation, now stored in the Connecticut State Library (CSL), and 171 monuments mark points along the line. A 1683 agreement between Governor William Leete of Connecticut and Governor Thomas Dongan of New York (and sanctioned by King Charles II) proclaimed the boundary between the two colonies. The following year, two surveyors, one from each colony, completed a survey of the border. Clarence Winthrop Bowen’s classic 1882 study, The Boundary Disputes of Connecticut, shows how two particular areas became the source of contention during the 18th century: the “panhandle” in the southwestern area of Connecticut containing the towns in Fairfield County, and “the oblong” in New York, a two-mile-wide, 60-mile-long strip of land cutting north and slightly east into Connecticut. Antagonistic relations between the colonies and later the states persisted throughout the period of the early republic as settlers ignored agreed-upon boundaries.

The 1683 agreement between Connecticut and New York referred to a “Wading Place”:

“It is agreed that the bounds, meers, or dividend between His Royal Highness’s territories – in America and the Colony of Connecticut forever hereafter shall begin – at — Lyon’s Point which is the eastern point of Byram River and from the said point to go as the river runneth to the place where the common road or “Wading Place” over the river is, and from said road or “Wading Place” to go north-northwest into the country…”

In 1684 surveyors went to Lyon’s Point, followed the Byram River, and located this “Wading Place.” There they found a natural monument: a granite ledge that they labeled “The Great Stone” in their survey report, filed in the Boundary Commissions Records at the CSL. The “common road” described in the agreement matches historian Charles Washington Baird’s description of the “old Westchester Path” in his 1871 book on the history of Rye, New York, Chronicle of a Border Town (Anson D. F. Randolph and Co.). He claimed the path had originally been used by Native Americans. This was likely because this shallow, narrow section of the river could be crossed on foot. According to Baird, the Westchester Path had been referenced as the boundary in deeds for many properties in Rye and Greenwich because it was “a well-known landmark.” Local residents worked to preserve knowledge of the location. Old men in Rye could recall being shown the “great rock at the wading place” and walking the town’s boundary line as young boys, and “it was usual to administer to some of the rising generation a sound flogging on the occasion, to insure their lasting remembrance of the localities pointed out.” When New York conducted a survey in 1860, surveyors drilled a bolt into the stone, ensuring that future generations could locate this point without relying solely on memory.

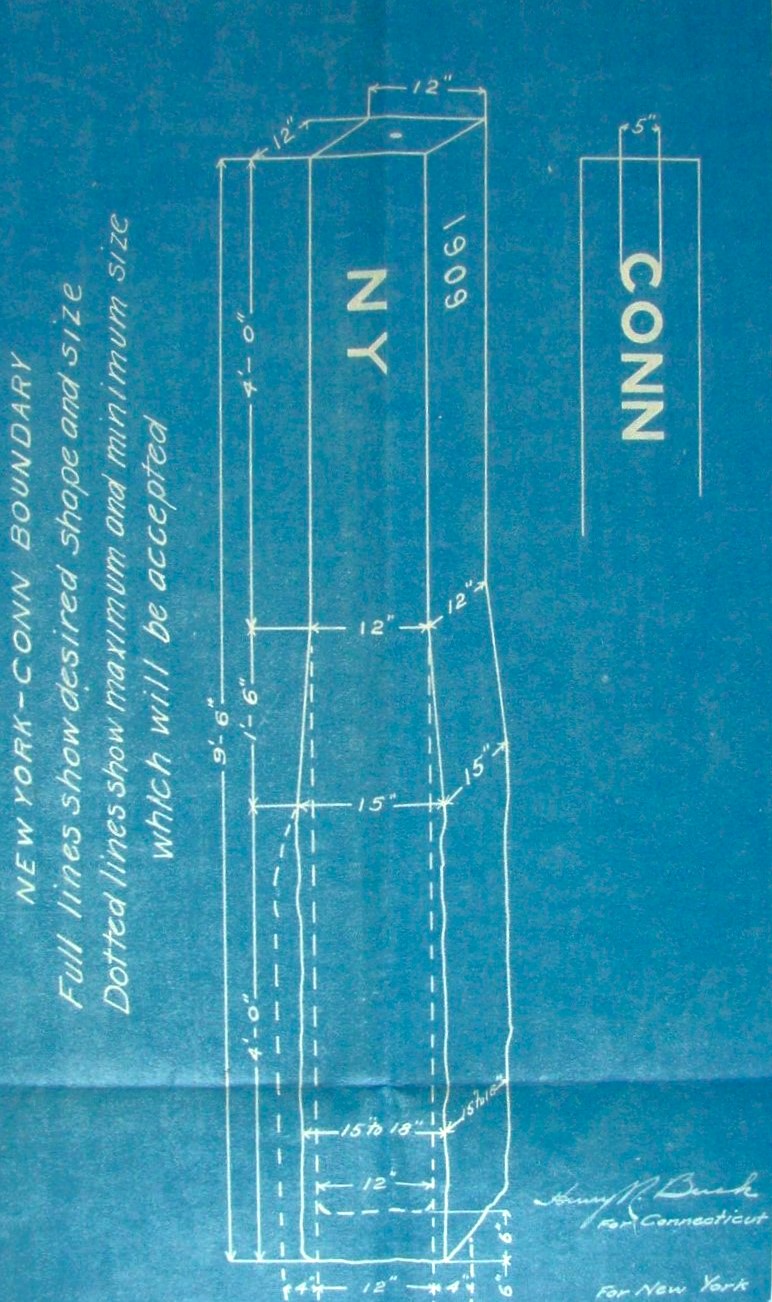

Connecticut and New York eventually worked together to conduct a joint re-survey in 1909. The team installed very clear monuments marking the line to avoid further disputes, and each monument was assigned a number. At the Wading Place, surveyors erected a concrete pier on the granite ledge into which they embedded a stone monument, aligning the center of the monument with the drill hole, according to Henry R. Buck, the Connecticut engineer at the head of the re-survey in his 1910 bound description (Bound #158) in the Records of the Boundary Commission. The survey and accompanying monumentation was accepted by both state legislatures in 1913.

The story of a monument is not finished even once it has been set. A 1958 report noted the monument had been buried beneath the pavement of a gas station. In 1961 Connecticut State Highway Commissioner Howard S. Ives dug into the pavement to uncover the top of the buried monument. He then poured concrete to fill the cavity and set a bronze disk directly over the center. Finally, he wrote up a report, photographed the disk, and filed it away at the CSL.

Today it is covered over with more pavement. A bridge has been constructed, streets have new names, and most people would not be familiar with a “Wading Place.” The “Great Stone” is hidden from view. Despite all these changes over the course of more than two centuries, the stewardship of generations of surveyors has preserved the location of this point. According to the Connecticut Department of Transportation, it is the oldest definitive point on the New York-Connecticut line.

The bronze disk says, “NEW YORK [No. 158] CONNECTICUT.” photo: Louis E. Sugland for the Connecticut State Highway Department, Connecticut State Library

The original photographer circled the location of the bronze disk in the gas station’s pavement. The Byram River is visible in the background. photo: Louis E. Sugland for the Connecticut State Highway Department, Connecticut State Library

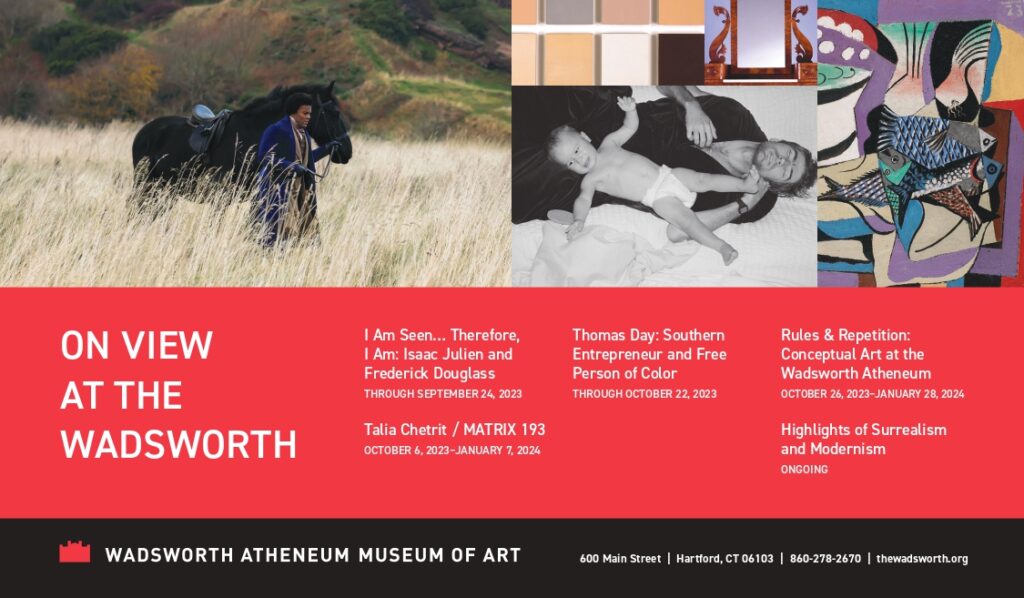

Below: Required specifications for the 1909 Connecticut-New York boundary monuments. photo: Connecticut State Library

Howard S. Ives submitted his report to the Connecticut State Librarian. photo: Connecticut State Library

Howard S. Ives submitted his report to the Connecticut State Librarian. photo: Connecticut State Library

A monument marking the boundary between Columbia and Lebanon today. photo: Arianna Basche and Mitch Curry

The method of setting monuments has evolved over time. An April 13, 1909 Hartford Courant article titled “Columbia” announced Columbia’s town selectmen’s intention to erect permanent monuments to delineate the town lines because the old monuments—piles of stone—were impossible to maintain, causing “considerable difficulty in accurately locating the bounds between the towns.” The article recognized, “[I]t is not strange that such bounds are often removed in common with other stone heaps in the field.”

Today, a 3-foot-tall stone monument, likely set in the aftermath of the aforementioned boundary line confusion, stands at an angle-point of the town line between Columbia and Lebanon, located in a wooded area on a privately owned farm. This monument was set at this spot based on the original location described in the boundary agreement between the two towns of 1805, after Columbia separated from Lebanon. The northwest side of the stone monument is labeled with a carved “C” to denote the direction of Columbia. An “L” is carved into the southeast side in the direction of Lebanon.

The northwest side (top) of the stone monument is labeled with a carved “C” to denote the direction of Columbia. An “L” (bottom) is carved into the southeast side in the direction of Lebanon. photos: Arianna Basche and Mitch Curry

Surveyors in the process of setting a new monument on the Connecticut-Massachusetts border in 1999 as part of the continual maintenance of the boundary line. 1999 Connecticut-Massachusetts Boundary Line Perambulation Report, Connecticut Department of Transportation

Like the paved-over bronze disk at the Wading Place, many monuments are hidden underground. Care needs to be taken to prevent these markers from being destroyed when ongoing development occurs. With foresight and planning, sidewalks and paved lots can be built in a way that keeps these markers safe and accessible. This concrete sidewalk in Hartford’s West End was carefully built around the stone monument, and a metal cap was slid on top. photo: Arianna Basche and Mitch Curry

This metal cover marks the location of a monument that is now covered by a newly built sidewalk. Using a screwdriver, a surveyor would be able to uncap this monument in order to conduct an accurate property survey of this Hartford city block. The cap warns passersby, “Do Not Disturb.” According to Connecticut General Statute Section 47-34a, “disturbing” a monument carries a fine of at least $500. photo: Arianna Basche and Mitch Curry

Explore!

Robert Baron, “Surveying Connecticut’s Borders,” Connecticut Explored, Spring 2012

Nicholas F. Bellantoni and David A. Poirier, “Sites Underwater Worth Preserving, Too,” Connecticut Explored, Spring 2009