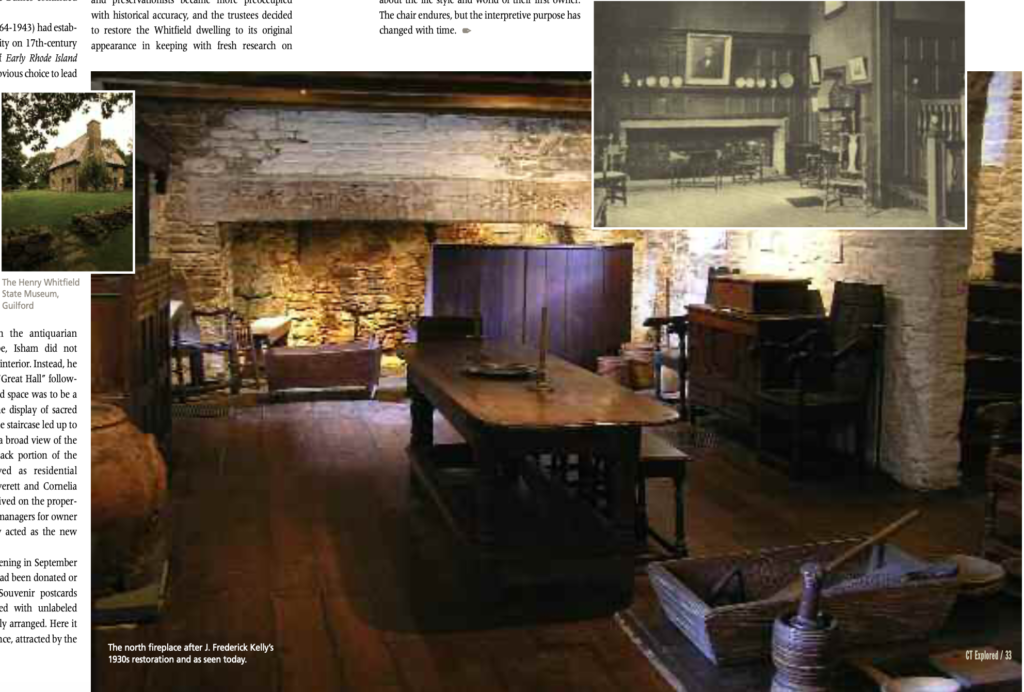

top left: The Henry Whitfield State Museum, Guilford; top right:

The north fireplace after J. Frederick Kelly’s 1930s restoration and as seen today; center: The north fireplace and displays as created by Norman Isham, c. 1904. All images courtesy of the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism

By Karin Peterson

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2010-2011

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

In recent years, scholars such as Patricia West in Domesticating History: The Political Origins of America’s House Museums (Smithsonian Institution Press, 1999) and Briann Greenfield in Out of the Attic (UMass Press, 2009) have “unpacked” the political and symbolic meanings of the early preservation movement and the related rise in interest in American architecture and antiques. By their reading, the chair by the window in the historic house museum of the early 20th century wasn’t just a place where the original inhabitant sat. The chair, like the building itself, was meant to convey a message to the visitor. Their joint mission was to educate the public—especially the foreign born— about American values and ideals.

Spurred by the Centennial International Exhibition of 1876 held in Philadelphia, interest in an idealized past became part of the American ethos and influenced architecture, interior design, and garden styles thereafter. The decade of the 1890s was a time of national stress, with waves of immigration, economic turmoil, and recession that challenged the heretofore comfortable world of the middle and upper classes. In response, nostalgia for “the good old days” intensified and led to the establishment of private patriotic membership organizations such as Sons of the American Revolution and the Daughters of the American Revolution, membership in which required proof of having an ancestor who fought in the Revolution. In Connecticut these fledging organizations, especially the all-female ones, energized the preservation movement with their efforts to protect buildings associated with venerated historic figures. The first historic house museum in the state open to the public was the Oliver Ellsworth Homestead, dedicated in 1903 and owned by the Connecticut Daughters of the American Revolution.

In 1897 the newly formed Connecticut Society of the National Society of Colonial Dames in America publicly expressed concern about the Old Stone House in Guilford, long recognized as an “ancient relic.” Privately owned by an out-of-state landlord, the house had deteriorated, and its future was uncertain. Pushed by the Dames, in 1900 the State of Connecticut purchased the property, now known as the Henry Whitfield State Museum, with the financial help of the Town of Guilford, the Dames, and other sources. Although the property was officially administered by a board of trustees appointed by the governor, the Dames continued to be involved.

Architect Norman Isham (1864-1943) had established his position as an authority on 17th-century houses with the publication of Early Rhode Island Houses (1895), and he was the obvious choice to lead the transformation of the private dwelling into a public museum. (Isham was later involved with many other restoration projects, including the Hyland House in Guilford, a house museum owned by the Dorothy Whitfield Historic Society. He published Early Connecticut Houses (1900) and many articles.)

A fire and a remodeling in the mid-19th century destroyed most of the Whitfield House’s original appearance. In keeping with the antiquarian mission of the museum-to-be, Isham did not attempt to recreate the original interior. Instead, he designed a two-story paneled “Great Hall” following medieval fashion. The grand space was to be a fitting exhibition gallery for the display of sacred artifacts of the past. A handsome staircase led up to a landing, which commanded a broad view of the room below. Isham left the back portion of the building untouched. It served as residential quarters for the caretakers, Everett and Cornelia (or Amelia) Dudley, who had lived on the property since the 1870s as the farm managers for owner Sarah Cone. Cornelia Dudley acted as the new museum’s curator until 1908.

By the time of its formal opening in September 1904, more than 2,000 items had been donated or lent for the new museum. Souvenir postcards show the Great Hall crammed with unlabeled artifacts of all types, haphazardly arranged. Here it was hoped that a diverse audience, attracted by the free admission, could learn about the first hardy pioneers and be inspired to moral and Yankee-style behavior. However, this house museum, like others, functioned more as a private clubhouse for an in crowd rather than the intended vehicle of social and culture integration.

Gradually, as the century progressed, historians and preservationists became more preoccupied with historical accuracy, and the trustees decided to restore the Whitfield dwelling to its original appearance in keeping with fresh research on 17th-century architecture and new restoration practices. Architect J. Frederick Kelly undertook the task, starting with the ell in 1930 and the main block in 1935-1937. It is Kelly’s interpretation that greets visitors today. The displayed artifacts, such as the chair by window, are still meant to convey messages to visitors, only now the lessons are about the life style and world of their first owner. The chair endures, but the interpretive purpose has changed with time.

Karin Peterson is museum director for the Connecticut Commission on Culture & Tourism. She previously wrote about Old New-Gate Prison (Summer 2006), Kent’s Iron Furnace (Fall 2006), and “Connecticut’s First—& Most Celebrated—Counterfeiter” (Summer 2008).