By Catherine Labadia and Julie Carmelich

Unknown Artist, view of the Colt Factory from Dutch Point or Little River, 1857. Oil on canvas. Image courtesy of the Elizabeth Hart Jarvis Colt Collection, Wadsworth Atheneum Museum of Art

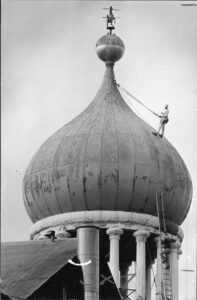

In 1955 the blue onion-domed factory in Hartford became the first project the newly established Connecticut Historical Commission tackled. The iconic Colt Armory had been threatened with demolition to make way for the Dike Highway (or Interstate 91). As the country grew after World War II, it developed an extensive interstate highway system that resulted in substantial losses to and impacts on our country’s natural, human, and historic environments. Activist groups flourished in response and put pressure on the U.S. Congress for legislated protections. During the 1960s and 1970s the federal government enacted a body of such laws, including the Transportation Act, the Clean Air Act, the Noise Control Act, the National Environmental Policy Act, and the National Historic Preservation Act.

Before the National Historic Preservation Act was passed, historic preservation was typically the work of individuals or organizations that coalesced around the preservation of a single building or object. The new legislation established operating principles for government-sponsored historic preservation efforts. The act’s preamble states two important principles: first, “the preservation of this irreplaceable heritage is in the public interest,” and, second, “the major burdens of historic preservation” should be shifted from private entities to the government. In other words, the act dictates that historic resources be held in public trust and that the government take responsibility for their preservation.

Colt Armory in Hartford, Connecticut. photo: Sean Pavone

The act has been amended several times to expand and clarify its implementation, but its cornerstones have withstood the test of time. Key provisions include the establishment of state historic preservation offices (SHPOs), the formation of the Historic Preservation Fund, the creation of the National Register of Historic Places, and the introduction of regulations known as Section 106. This federal policy shifted historic preservation from being regarded as voluntary to being understood as necessary.

Uniquely poised between the federal government and local communities, SHPOs are critical to implementing historic preservation initiatives and mandates. In 1966 Connecticut’s SHPO was established as a division of the earlier Connecticut Historical Commission. This office administers federal and state grant programs, creates and maintains historic-property inventories, provides technical guidance and advice, and assists state and federal agencies with compliance requirements pertaining to historic preservation. These initiatives are ultimately tied to the National Register, a mechanism for communicating significant history through the process of designation.

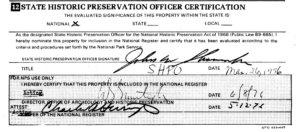

Buildings, districts, archaeological sites, structures, and objects can be listed on the National Register if they meet at least one of four criteria: the candidate site or object must be associated with a notable event or trend, related to a person of transcending importance, representative of a distinctive style or the work of a master, or possess research potential; in most cases they also are required to be older than 50 years. These simple concepts allow for changing interpretations of history and have been used to recognize a wide variety of historic resources. It should be no surprise that the Colt Industrial District was among Connecticut’s first properties to be designated. Although a listing on the National Register is primarily honorific, it does confer some protections and incentives, including special considerations under Section 106 and maintenance or rehabilitation funding.

The Colt Industrial Complex’s application,

signed by the State Historic Preservation Officer,

Director of Archaeology and Historic Preservation,

and Acting Keeper of the National

Register. image: National Register of Historic Places

The historical significance of place is central to the application of Section 106, the implementing regulation that requires federal agencies to consider the impacts of their actions on historic resources. If Section 106 had been in place when Interstate 91 was being planned, the federal government would have been required to engage in consultation with concerned citizens or stakeholders to identify ways to avoid impacts to the Colt Armory. The review process requires public involvement in the form of public notices or meetings, strengthening the notion of a shared foundation for historic preservation. In 2022 SHPO reviewed approximately 3,000 state- or federally-funded

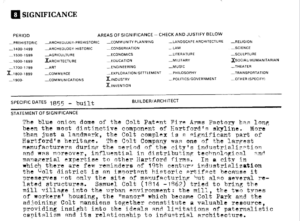

The “Historical

Significance” section of the Colt

Industrial Complex’s application for

inclusion on the National Register

of Historic Places.

image: National Register of Historic Places

or permitted development projects pursuant to state and federal legislation. Most of these projects did not involve plans that would affect properties listed on or eligible for listing on the National Register. Some projects, though, posed potential impacts to historic resources. In these cases, the responsible agency works with affected stakeholders and SHPO to avoid or minimize the effects of the proposed development on historic resources.

Historic preservation is not about freezing places in time but keeping history active within the continuum of human land use. The most significant investment in historic properties that catalyzes historic building re-use comes from the Historic Tax Credit program, established as part of the Tax Reform Act of 1976. This program works with a framework initially created by the National Park Service in

Partially completed

construction on I-91. The Colt

factory is visible in the distance,

November 1945.

image: Connecticut Museum of Culture

and History

1971 for the acquisition and development of properties listed on the National Register. This framework provided treatment standards for the stabilization, reconstruction, and restoration of historic properties. After the Tax Reform Act was passed, four additional treatment standards were added to the original three: acquisition, protection, preservation, and rehabilitation of historic properties. Together, these guidelines, known as the U.S. Secretary of the Interior’s Standards for Rehabilitation, became the basis for how historic preservation projects are carried out.

In 1995 a substantial revision to the standards was published in the Code of Federal Regulations. This publication replaced the 1976 collection of seven guidelines with the four in current use: preservation, restoration, reconstruction, and rehabilitation. Since 1995 additional bulletins have offered guidance on incorporating energy efficiency into historic buildings and on adapting buildings for flood events. The standards continue to evolve as new building materials, environmental constraints, and energy requirements emerge and affect the ways in which historic buildings are preserved and reused. This flexibility in application demonstrates that, contrary to the individual meanings of the words “historic” and “preservation,” the practice is about adapting to contemporary society and preparing for change.

Although advocacy saved the Colt Armory from a wrecking ball, the state and federal Historic Tax Credit programs brought it back to life. Although it was a challenging project, it would be hard to imagine the gateway into Hartford along Interstate 91 without the iconic blue onion dome. Multiple buildings within the Colt Industrial Historic District have been rehabilitated and put back into use, with costs exceeding $100 million over the past 20 years. This redevelopment would not have been possible without the state and federal Historic Tax Credit program, which contributed more than $22 million. With a new identity as Colt Gateway, this historic complex is considered an economic driver.

The Coltsville Historic District. image: Historic American

Buildings Survey of Connecticut, Wikimedia Commons

The National Historic Preservation Act opens with a statement of purpose, that “the spirit and direction of the Nation are founded upon and reflected in its historic heritage.” While the initial impetus of this sweeping legislation was to save iconic historic places like the Colt Armory from loss, the application of the act has evolved to include historic preservation as an important component of quality of life, an environmentally sustainable practice, and a strong economic driver. Moving forward, the diligent application of historic preservation law has strong potential for designing and building a better future.

Catherine Labadia is the deputy state historic preservation officer and staff archaeologist for the State Historic Preservation Office.

Julie Carmelich is the historic tax credit coordinator and historian for the State Historic Preservation Office.

Explore!

Connecticut Register of Historic Places portal.ct.gov/DECD/Content/Historic-Preservation/01_Programs_Services/Historic-Designations/National-Register-of-Historic-Places

Mary Donohue, “National Historic Preservation Act: 40 and Fabulous,” Connecticut Explored, Winter 2005/2006

Connecticut Explored received support for this publication from the State Historic Preservation Office of the Department of Economic and Community Development with funds from the Community Investment Act of the State of Connecticut.