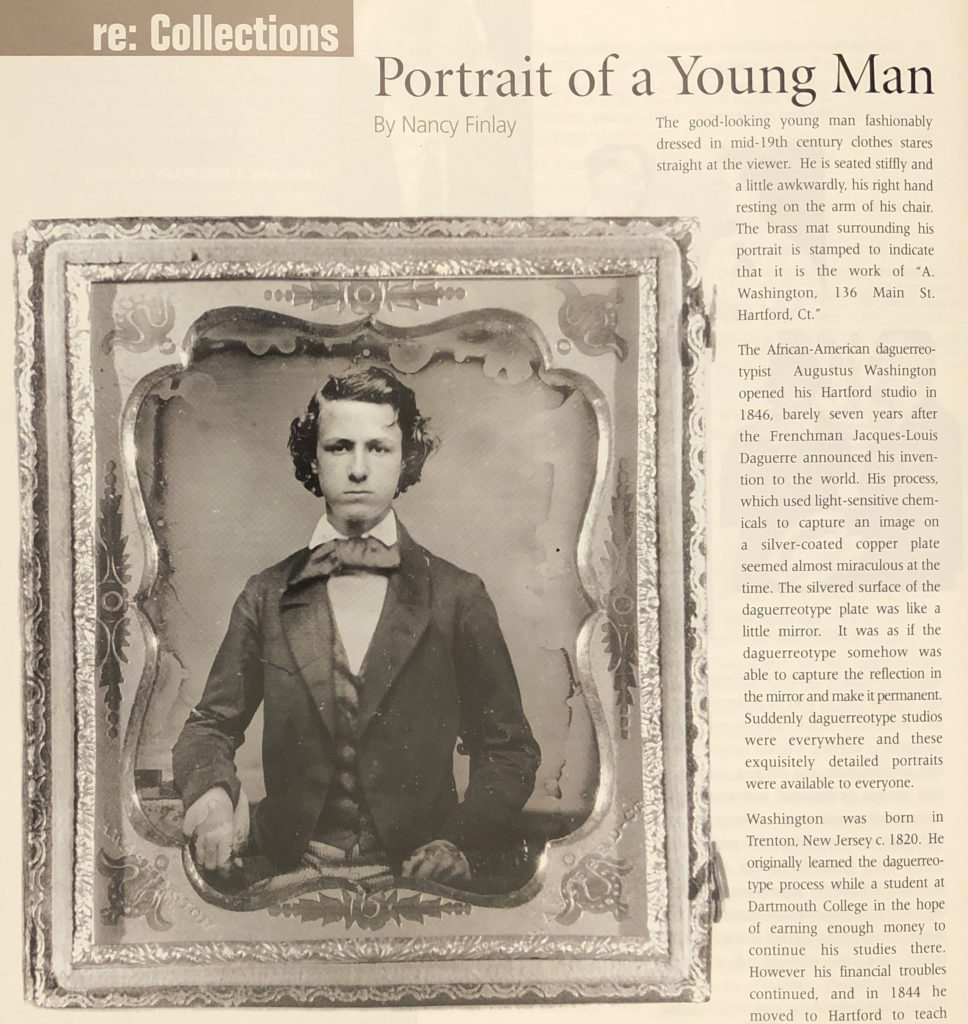

Charles Edwin Bulkeley by photographer Augustus Washington, c. 1852. Connecticut Historical Society Museum, Hartford

re: Collections — Portrait of a Young Man

By Nancy Finlay

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2004/2005

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

The good-looking man fashionably dressed in mid-19th century clothes stares straight at the viewer. He is seated stiffly and a little awkwardly, his right hand resting on the arm of his chair. The brass mat surrounding his portrait is stamped to indicated that it is the work of “A. Washington, 136 Main St. Hartford, Ct.”

The African-American daguerreotypist Augustus Washington opened his Hartford studio in 1846, barely seven years after the Frenchman Jacques-Louis Daguerre announced his invention to the world. Daguerre’s process, which used light sensitive chemicals to capture an image on a silver-coated copper plate seemed almost miraculous at the time. The silvered surface of the daguerreotype plate was like a little mirror. It was as if the new process somehow was able to capture the reflection in the mirror and make it permanent. Suddenly daguerreotype studios were everywhere and these exquisitely detailed portraits were available to everyone.

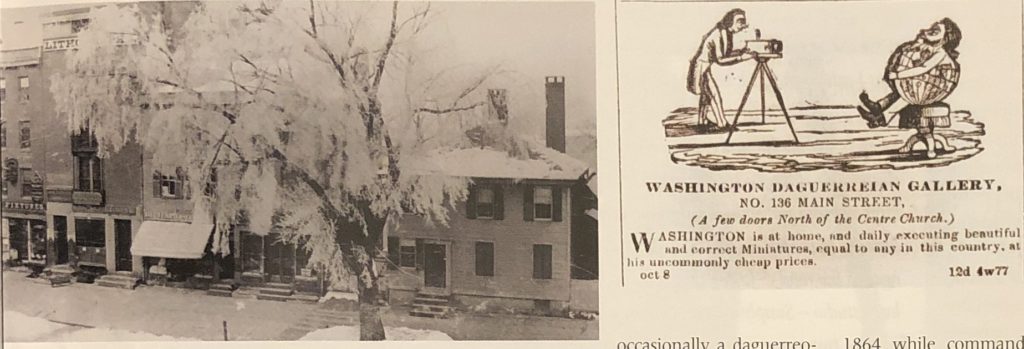

Washington was born in Trenton, New Jersey around 1820. He originally learned the daguerreotype process while a student at Dartmouth College in the hope of earning enough money to continue his studies there. However his financial troubles continued, and in 1844 he moved to Hartford to teach at the Colored District School operated by the Reverend James C. Pennington at 12 Talcott Street. Two years later he set up a “Daguerreian gallery” in the Wavery Building; by May 1847 he had moved to the Kellogg Building at 136 Main Street, across the street from the Wadsworth Atheneum. Although he was not Hartford’s first daguerreotypist, he was one of the most successful. His prices ranged from 50 cents to 10 dollars, and his patrons included some of Hartford’s most prominent citizens. Many of the earliest daguerreotype studies lasted no more than a few months, but Washington remained in business until 1853 when he and his family left to join the African American colony in Liberia.

left: Main Street, Hartford, early 1850s by photographer R. S. DeLameter. Augustus Washington’s studio was in the second building from the left. right: advertisement, The Hartford Daily Courant, October 1, 1852. Connecticut Historical Society

Charles Edwin Bulkeley, the boy in this portrait, was the son of Aetna founder Eliphalet Adams Bulkeley and his wife Lydia. Charles, the oldest son in a family of three boys and a girl, was born in East Haddam on December 16, 1835. The family moved to Hartford in 1847. In 1852, when this portrait was made, Charles was 16 years old and about to enter Yale College. He could have walked from his family home at 38 Church Street to Washington’s daguerreian gallery in just a few minutes. There he would have climbed the stairs to the top floor where skylights provided the ample light required for the long exposures, usually about 20 seconds. Charles’s rather rigid pose and solemn expression are explained by the fact that he had to hold absolutely still for almost half a minute. That is why his hand is supported by the arm of the chair; his head would also have been supported by a head rest. Many people complained about the need to remain motionless for so long, and occasionally a daguerreotype survives in which the sitter is partially blurred from movement.

Washington not only arranged Charles’s pose and exposed the plate in a large, rather crude camera, he also developed the daguerreotype, sealed it in an airtight package with a glass cover sheet, and mounted it in a leather-covered case with a brass mat surrounding the portrait. The fact that Washington’s name and address were stamped on the mat, or sometimes embossed on the cover of the case, is unusual. Most daguerreotypists did not sign their work so prominently. His parents must have liked Charles’s portrait because a year or two later Washington made their portraits also. Their daguerreotypes, in contrast to Charles’s, are mounted in silver-bordered cases, the most expensive and elegant type of case. All these early daguerreotype portraits were treated like precious objects. As with painted miniatures, each daguerreotype was unique: there was no negative and the only way to get a copy was to take another daguerreotype — or later a photograph — of the portrait.

By the 1860s, the exquisite daguerreotype on its silver-coated plate had been largely superceded by the true photograph on paper, printed from a negative, which allowed the production of as many copies as desired. Charles E. Bulkeley had himself photographed as a dashing young officer after enlisting in the First Connecticut Volunteer Infantry in April 1861, following the fall of Fort Sumter. When that unit was disbanded following the first Battle of Bull Run, Charles signed up with the First Connecticut Heavy Artillery. He died February 13, 1864 while commanding Battery Garreche, near Falls Church Virginia.

Augustus Washington continued to take daguerreotypes for a short time after emigrating to Liberia, but agriculture and trading soon proved more lucrative sources of income. He also pursued a political career. He was elected to three terms in the Liberian House of Representatives, where he twice served as Speaker of the House, and one term in the Liberian Senate. When he died in 1873, he was one of Liberia’s most distinguished citizens and his death was mourned as a “severe loss” to all of Western Africa.

The Connecticut Historical Society Museum collection includes eight daguerreotypes by Augustus Washington and a large collection of photographs of the Bulkeley family. A selection of Washington daguerreotypes may be viewed on The Connecticut Historical Society Museum’s e-museum web site. For more information, call 860-236-5621 ext. 236.

Nancy Finlay is curator of graphics at The Connecticut Historical Society Museum

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s art history on our TOPICS page.

Read more stories about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.