By Betsy Golden Kellem

One of the central promises made by the Connecticut Constitution of 1818 was the disestablishment of the state’s long-official Congregationalist faith. But such dramatic changes in attitude and practice are neither quick nor easy. One of the starkest examples of the interplay between old structures and new voices emerged in 1832, when Phineas Taylor Barnum was convicted for libel thanks to the anti-clerical journalism of his Herald of Freedom newspaper. (There was, alas, no song about this event in The Greatest Showman). Through a well-publicized trial and conviction, not to mention the parade he threw upon his release from jail, Barnum’s role as a Universalist and a visionary media agent allowed him to push back against power structures and turn the public narrative away from the traditional Standing Order.

At the time of the Revolutionary War, Connecticut was uniquely situated: most other colonies, after declaring independence from Britain, legitimized themselves by adopting new constitutional documents. Connecticut, considering itself a model of stable, sustainable self-government under its Fundamental Orders, simply reaffirmed the substance of its colonial charter. Stability was the state’s stock in trade, and Connecticut residents took considerable pride in their characterization as the “Land of Steady Habits” – an epithet that has alternately through the state’s history been used both to praise Connecticut’s sober Yankee reliability and to roll eyes at its pigheaded inflexibility.

Practically speaking, the effect of these steady habits was that the same elite families, of the same Federalist bearing and conservative Congregationalist faith, ran the state for generations. They became known as the “Standing Order.” As Andrew Siegel wrote in his article “Steady Habits Under Siege: The Defense of Federalism in Jeffersonian Connecticut,” the establishment felt that, under their care, “[a]ll was bright, all was good, all was great.”

Day-to-day life started to feel more complicated in Connecticut at the turn of the 19th century, though, and a new and growing voice in the state began to insist that things in fact were not so unfailingly bright, so good, so great. For one, the effects of the chilly “Little Ice Age” climate, as described by Sam White in his book A Cold Welcome (Harvard, 2018), made agriculture harder. At the same time, many of the state’s employable young men were leaving to look for better work or open land in the state’s Western Reserve. The population was visibly diversifying in faith and ethnicity, and, as George McLean pointed out in Connecticut Woodlands: A Century’s Story of the Connecticut Forest and Park Association, 1800-1836 (Connecticut Forest & Park Association, 1995), deforestation and overfarming began to affect the state’s productivity. Dissenting voices criticized the Federalists’ 1801 “Stand-Up Law,” which eliminated secret ballots and asked men to vote by physically standing up to be counted for their position. A prickly 1800 presidential race, decided in the U.S. House of Representatives by contingent election, combined with bitter opposition to the War of 1812 to threaten the security to which many Federalists had become accustomed. Many started to clamor for change.

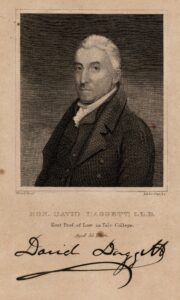

The first two decades of the 19th century posed a sudden shift for a state that didn’t like surprises in its land, its religion, its people, or its practices. The leading voices of the Standing Order insisted that without the right time-tested guidance (their own), the state would quickly go to hell in a handbasket. For instance, the Connecticut jurist and Yale Law school co-founder David Daggett published a firm and fusty pamphlet called “Steady Habits Vindicated” in 1805, urging citizens to resist changing the state structure of government. Daggett insisted that the state was on a precipice, and that “[i]f we greatly decline from that purity of morals, from that republican simplicity, and from those sober, orderly and virtuous habits which have heretofore been the ornament and the safeguard of this state, the overthrow of the government and the loss of civil privileges will be the certain consequence.” When Oliver Wolcott Jr. was elected governor in 1817 as the candidate of the Toleration Party, disestablishment of state-sponsored Congregationalism was officially on the table. Electors ratified the Constitution of 1818, which made it official, in October.

Title page of David Daggett’s, Steady Habits Vindicated, 1805. image: Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Title page of David Daggett’s, Steady Habits

Vindicated, 1805. image: Beinecke Rare Book and

Manuscript Library

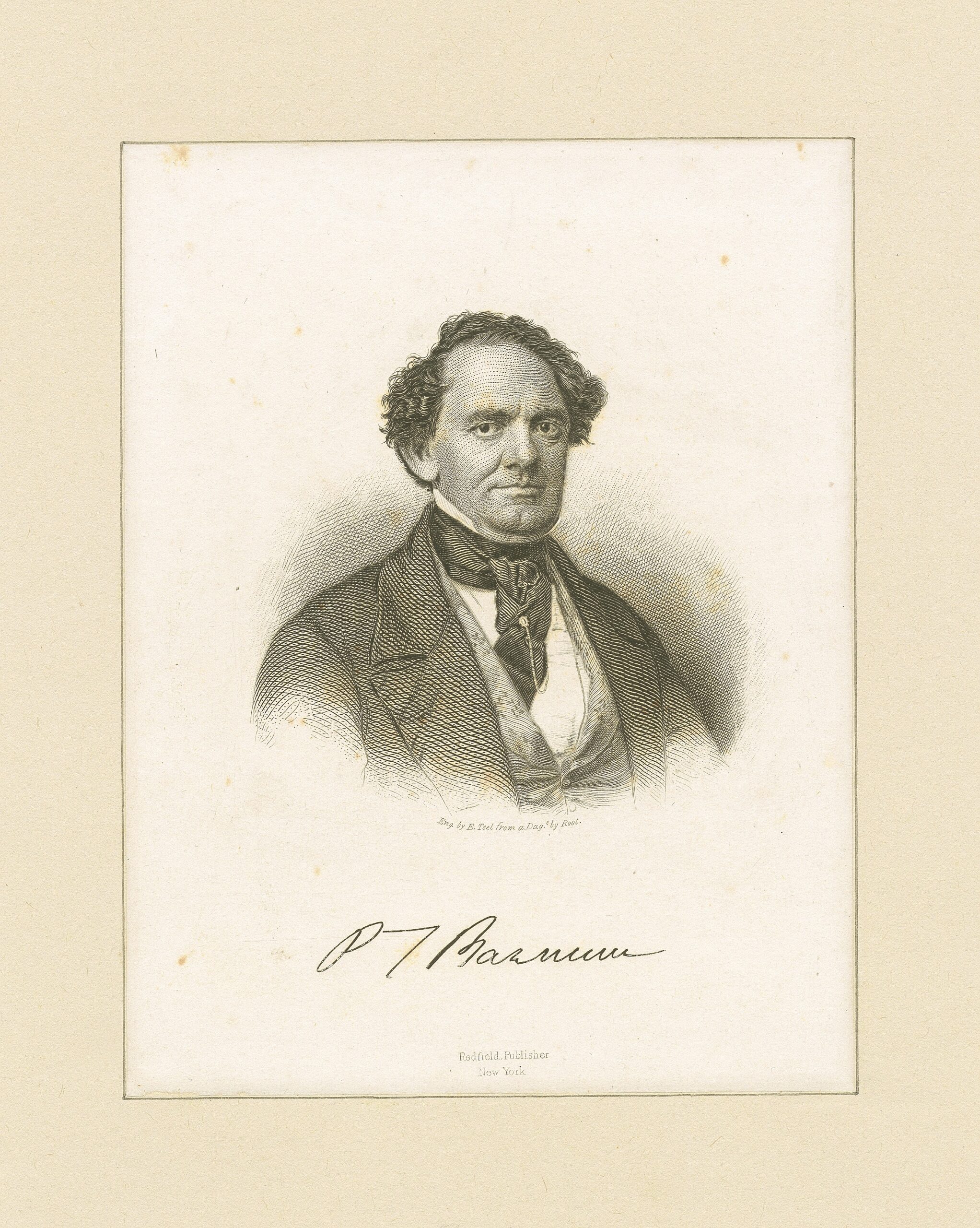

It was into this highly conflicted Connecticut that Phineas Taylor Barnum was born, on July 5, 1810. He did not live in the rich Connecticut River valley among the state’s elite families but rather was born and grew up in Bethel, a southwestern town near Danbury. Young Barnum – nicknamed “Tale” during his childhood – had been named for his maternal grandfather Phineas Taylor, one of Bethel’s prominent citizens. He saw his grandfather as a role model in every way: the older man stood out for his wealth and his Universalist faith, and furthermore had not only a puckish Yankee sense of humor but, in Barnum’s words, a “great desire to excel.” All these traits would show themselves in young Tale before long.

Barnum tried his hand at a variety of business ventures in his young life. Just shy of 18 years old, he returned home and opened a fruit and confectionary store in Bethel, according to his autobiography Struggles and Triumphs (Courier Company, 1889). When the business turned a respectable profit, Grandpa Phin suggested young Barnum might try his hand at lotteries. P.T. soon built a network of agents to sell tickets throughout the state, and in his 1855 Life of P.T. Barnum (Redfield, 1855) Barnum notes that his “lucky office” readily sold “from five hundred to two thousand dollars’ worth of tickets per day.”

Herald of Freedom and Gospel Witness, Vol. II, New Series 9,

December 12, 1832. image: Barnum Museum

In 1831 P.T. Barnum was married to former seamstress Charity Hallett, flush with cash, and feeling confidently established in life and business. This confidence formed in Barnum “a period of strong political excitement,” as he put it in his autobiography. He disapproved of mouthy clergy who even after the 1818 Constitution wanted to run state politics according to their own moral agenda (and, who, not coincidentally, disapproved of the very same lotteries that were then making Barnum a ton of money). P.T. Barnum was a devoted and earnest Christian, but cared for neither the substance nor the attitude of Congregationalism, which in his eyes existed mostly to scare the pants off of small children. He recalled in Why I Am a Universalist (Universalist Publishing House, 1893) attending “prayer meetings where I could almost feel the burning waves and smell of the sulphurous fumes.” The Universalist faith Barnum had learned from his beloved grandfather, in which everyone made it to a happy ending, seemed a lot friendlier than Congregationalism’s grim predestination.

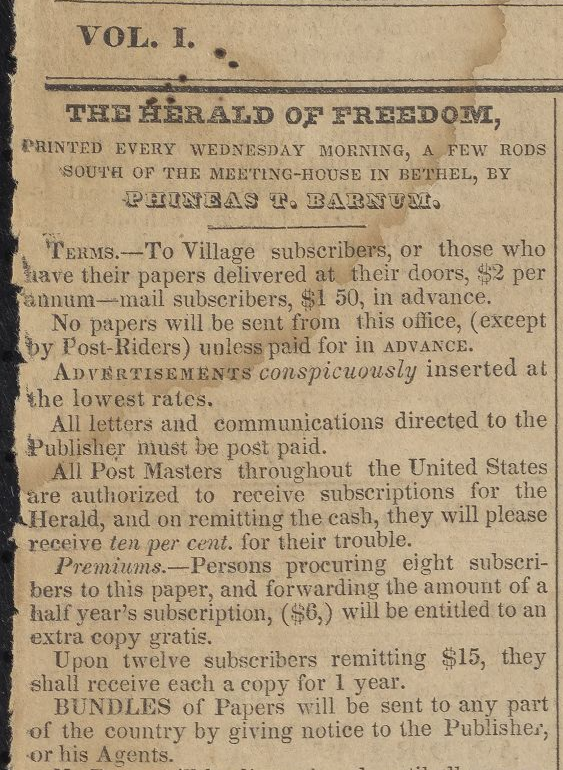

Barnum’s career in publishing came about in large part because he had written a letter in 1831 to the editor of the Danbury Recorder, expressing an opinion that religious revivalism was leading Christianity and politics to sit a little too closely for comfort. When the local editors refused to publish his letter, Barnum decided the best way to get his letters printed was to start up his own paper. Fashioning himself as a crusader for liberal values and rational discourse, he bought a printing press and “with boldness and vigor” promptly began publishing a weekly paper dubbed the Herald of Freedom, which grandly proclaimed: “For I have sworn upon the Altar of God, eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.” A masthead announced that the paper was “Printed every Wednesday morning, a few rods from the meeting-house in Bethel, by Phineas T. Barnum.” The annual fee was $2 for home delivery, $1.50 paid in advance for a mail subscription.

The Herald of Freedom was a mix of articles, op-ed columns, and local business advertising, all printed in a weekly edition of a few pages. As editor and publisher, Barnum targeted Connecticut theocracy, pointing out clergy hypocrisy and church-and-state abuses, and peppering the stew with typically saucy 19th-century cautionary tales involving nutty revivalist preachers and poor impressionable young minds. The Herald printed all sorts of rumors and rumblings alongside Barnum’s very blunt op-ed pieces, in which he went after his subjects, their beliefs, their lack of rigor, and even their manners. He was not shy, believing that “the result of conflicting opinion and open discussion can only be truth; and that no opinion deserves to be protected, which cannot protect itself.” Barnum remained on the Herald of Freedom masthead for three years, during which he was, “without the caution of experience or the dread of consequences,” thrice prosecuted for libel. One case resulted in a fine, and another was withdrawn; but in 1832 the third charge stuck, after Barnum had criticized Bethel’s Seth Seelye, a prominent merchant and deacon, for “taking usury of an orphan boy” (Struggles and Triumphs).

The judge assigned to Barnum’s case was none other than David Daggett, who was still resolutely clinging to his beliefs. In Atwood v. Welton, an 1828 state supreme court case, the judge had ruled that witness testimony couldn’t be credibly admitted without a religious oath to belief in a Christian afterlife of heaven and hell. Since Barnum and his fellow Universalists believed salvation would be extended to all people, they lacked the Biblical rigor to be taken seriously by the judge. Barnum knew he was in for it and wrote a panicky letter on August 8, 1832 to local lawyer Charles Hawley. “I have got it adjourned for counsel until tomorrow at 11 o’clock A.M.,” Barnum scribbled, in a letter that survives in the Barnum Museum collections. He pleaded, “I wish you without the least fail to be here and assist me.” His correspondence may have revealed him to be a frightened 20-something, but publicly Barnum stayed on-brand, keeping a hand on the tiller and retaining his good humor. He boldly referred to Daggett as a “lump of superstition” and proclaimed himself flattered by the fact that the establishment was coming after him with the biggest hammer it could lay hands on. (The opposing legal team, noted the Herald’s August 29 issue, included the state’s lieutenant governor.) If he was nervous, Barnum didn’t let on.

Daggett’s judgment, which is held by the Connecticut State Library, succinctly dismissed Barnum as a “person of an evil and wicked disposition,” sentenced him to a 60-day jail term, and levied a fine of $100. Barnum was jailed in Danbury in the fall of 1832, and in characteristic fashion made lemonade out of even this. He cheerily recalled that he had his cell carpeted and wallpapered before his arrival and could hardly even consider boredom, much less public shame, amidst the steady flow of visitors. He would later thank Judge Daggett for gaining him a thousand subscribers, though privately he loathed the judge, considering him an oppressively orthodox old man who could do the state of Connecticut no better favor than to either retire or die.

Then, as now, partisan journalists eagerly took sides, and for every paper that proclaimed Barnum a champion of liberalism and free speech, there was another that considered him a vulgar seditious upstart. The Hartford-based American Mercury of December 10 dismissed Barnum as the publisher of a “Slang Herald in Fairfield County,” and responded to his comments about Judge Daggett by saying “Such attacks upon a Judicial officer, for a faithful discharge of his duty, are disgraceful.”

Jail time appears to have freed Barnum’s tongue to utter even sharper words than the ones that had landed him behind bars in the first place. A jailhouse edition of the Herald of Freedom in October 1832 described “The Prison Dream,” a florid allegory in which Barnum claimed to have dreamed a legion of black-clad Connecticut clergy scaling a hill toward the Temple of Popularity, literally trampling a clutch of graybeard Revolutionary War veterans in their quest for the summit. Only when the goddesses of Justice and Reason arrive to scatter the mess does the resulting whirlwind reveal wolf’s hair underneath the clergymen’s vestments, and cloven hooves inside their shoes.

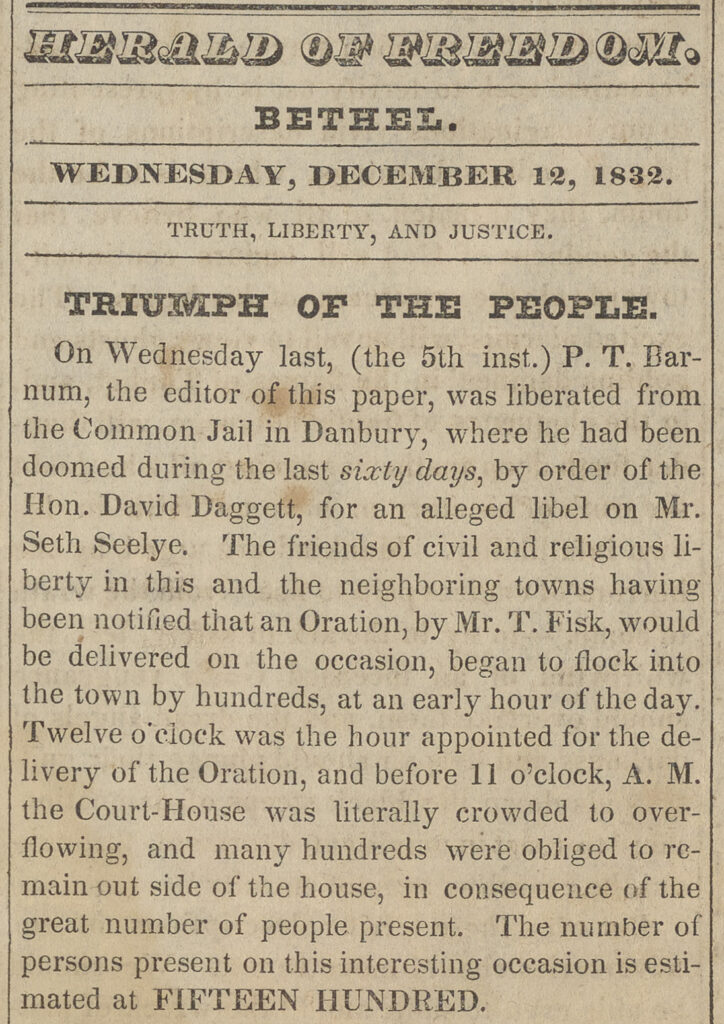

By the time two months of jail time had passed, the Herald was better known than ever, and Barnum had prepared a grand event to celebrate his release. And a celebration it was: the Herald of Freedom’s account described a cheering crowd, a cannon salute, a brass band, Barnum arriving in a gallant horse-drawn coach. And flags. Lots and lots of American flags. The event culminated in a celebration gala at the Danbury court house, at which the Reverend Theophilus Fisk addressed the claimed 1,500 attendees on the topic of free speech. In an America that supposedly held a free press dear, Fisk argued, how could such a man as Barnum be thrown into a dank, spare cell? Fisk claimed that “The most dangerous craft (except Priestcraft,) which we have to dread, is DUMB-craft. The man who dares not express his honest opinion at all times and under all circumstances – who can stand by, and hear what he conceives to be heaven’s truth, perverted, travestied, caricatured, and not open his mouth – that man is ready to be rode like a beast of burden – he should change shapes with the spaniel and wear a collar about his neck.”

Herald of Freedom and Gospel Witness, Vol. II, New Series 9,

December 12, 1832. image: Barnum Museum

A few hundred locals joined the brass band in marching Barnum three miles home from Danbury to Bethel (and then, hopefully equally joyfully, honking their way back again). “No one will be surprised,” reflected Barnum in his memoir, “that I should have regarded such a return to my home and family as a triumphal march.” In circumstances that would have doomed a lesser man to scorn as a hack libeler, Barnum had successfully seized the narrative and styled himself a champion of democracy.

The Herald of Freedom continued printing until 1835, at which point Barnum sold it to his brother-in-law and embarked on what would become his unparalleled career in show business. Nonetheless, the libel trial stands as a remarkable example of how Barnum, even as a young man, saw himself as a gadfly. He clearly hoped to demonstrate that a spirit of joyful experimentation and individual empowerment could open opportunity and voice beyond the old Standing Order; in Struggles and Triumphs Barnum recalled that “this new enterprise reflected credit upon my ability, as well as energy, and so I may be excused if I now recur to it with something like pride.”

Betsy Golden Kellem is the Emmy-nominated host of the Barnum Museum series “Showman’s Shorts” and a published author on circus and entertainment history.

Explore!

The Barnum Museum

820 Main Street, Bridgeport

203-331-1104

barnummuseum.org

As of this writing, the museum is closed to the public for renovations. Visit the Barnum Museum YouTube channel for more than 100 videos about the museum and its collections.

Learn More!

Bruce E. Hawley, “P.T. Barnum Builds a City,” Connecticut Explored, Winter 2021-2022. ctexplored.org/p-t-barnum-builds-a-city/

Eric Lehman, “Tom Thumb and the Age of Celebrity,” Connecticut Explored, Spring 2015. ctexplored.org/tom-thumb-and-the-age-of-celebrity/

Grating the Nutmeg Episode 60: Special CPTV Audio Documentary: The P. T. Barnum You Never Knew. Ctexplored.org/listen or gratingthenutmeg.libsyn.com