Drawn by H. W. Herrick; engraved by J. W. Watts, “Reading the Emancipation Proclamation,” S. A. Peters & Co., Hartford, Connecticut, 1864. Simpson Collection News of the Emancipation Proclamation reached regions of the country at different times. Frederick Douglass may have been one of the first African Americans to hear the news, but there were many who did not know that Lincoln had proclaimed their freedom until months later.

By Wm. Frank Mitchell

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2012-2013

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

All images are from The Amistad Center for Art & Culture.

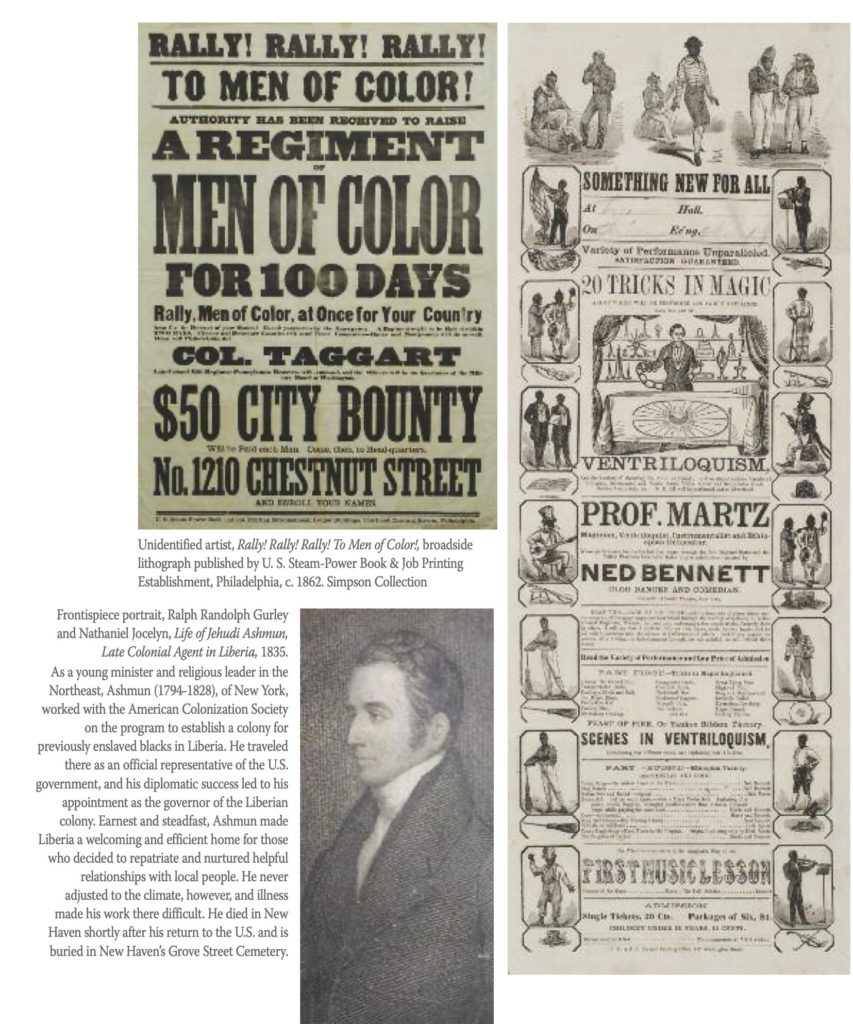

Emancipation!, a special exhibition at The Amistad Center for Art & Culture on view May 18 to September 15, 2013, explores the concept of freedom in America in the Civil War era.

In December 1865, Confederate General Robert V. Richardson wrote to a French banker, “The property personal and real, as a general thing belong, in these States, to the whites. The emancipated slaves own nothing, because nothing but freedom has been given to them.” As Civil War historian Eric Foner suggests, the concept of freedom and the word’s actual definition have long been the source of persistent disagreements. Was freedom a spiritual escape, emotional contentment, or a physical state? Should formerly enslaved blacks have received land or some form of payment for their years of labor? Or was the opportunity to pursue individual success compensation enough? General Richardson spoke for many slaveholders who agreed that slaves deserved nothing but their personal freedom. And though some believed they would ultimately receive some reparation—“40 acres and a mule” was a popular suggestion—President Lincoln’s 1863 Emancipation Proclamation granted nothing but freedom to certain enslaved people, and it came with conditions. Undoubtedly the conversation about the realities of freedom in ante-bellum America was as complicated as the conversation about race in the 21st century, although mid-19th-century Americans were far more sanguine about the boundaries of freedom and its potential manipulations, impediments, and denials.

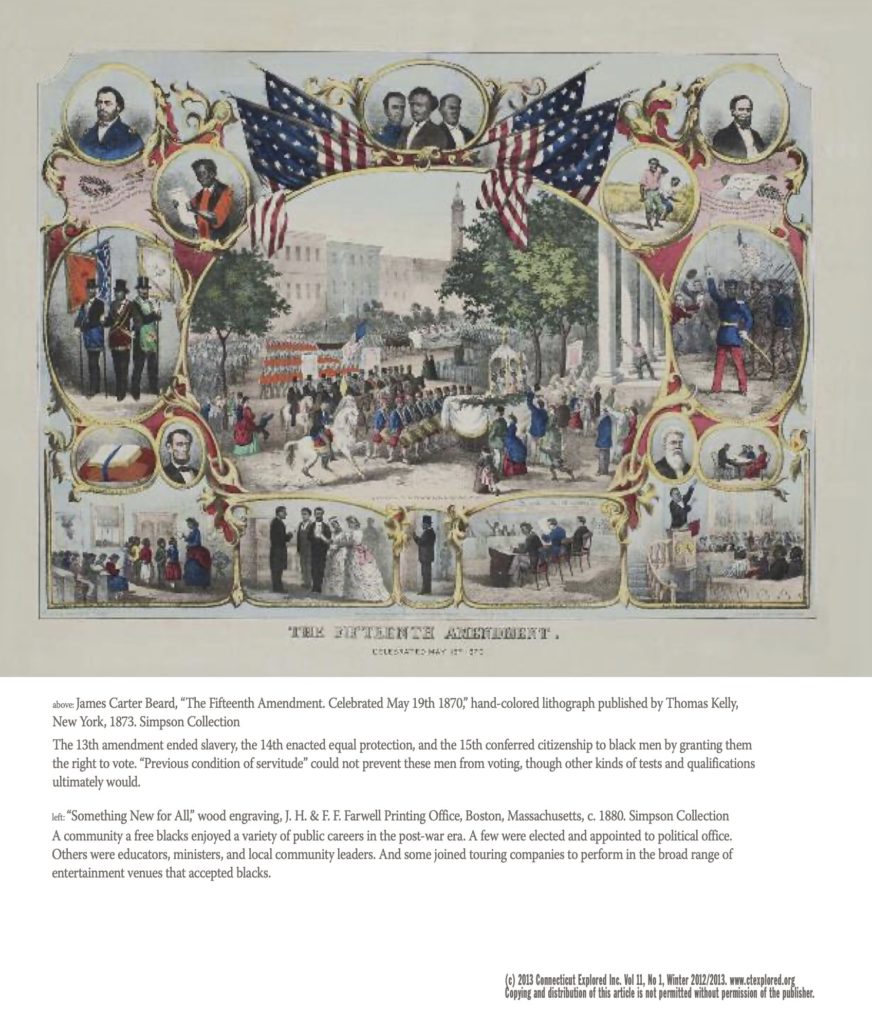

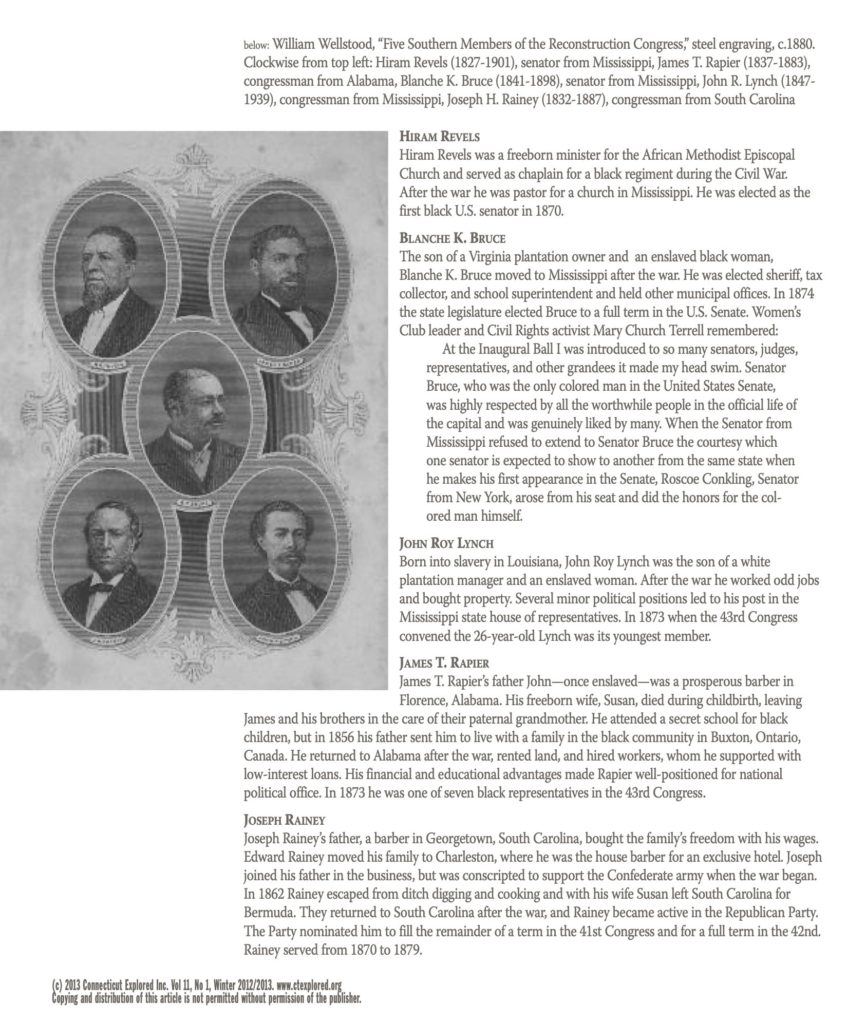

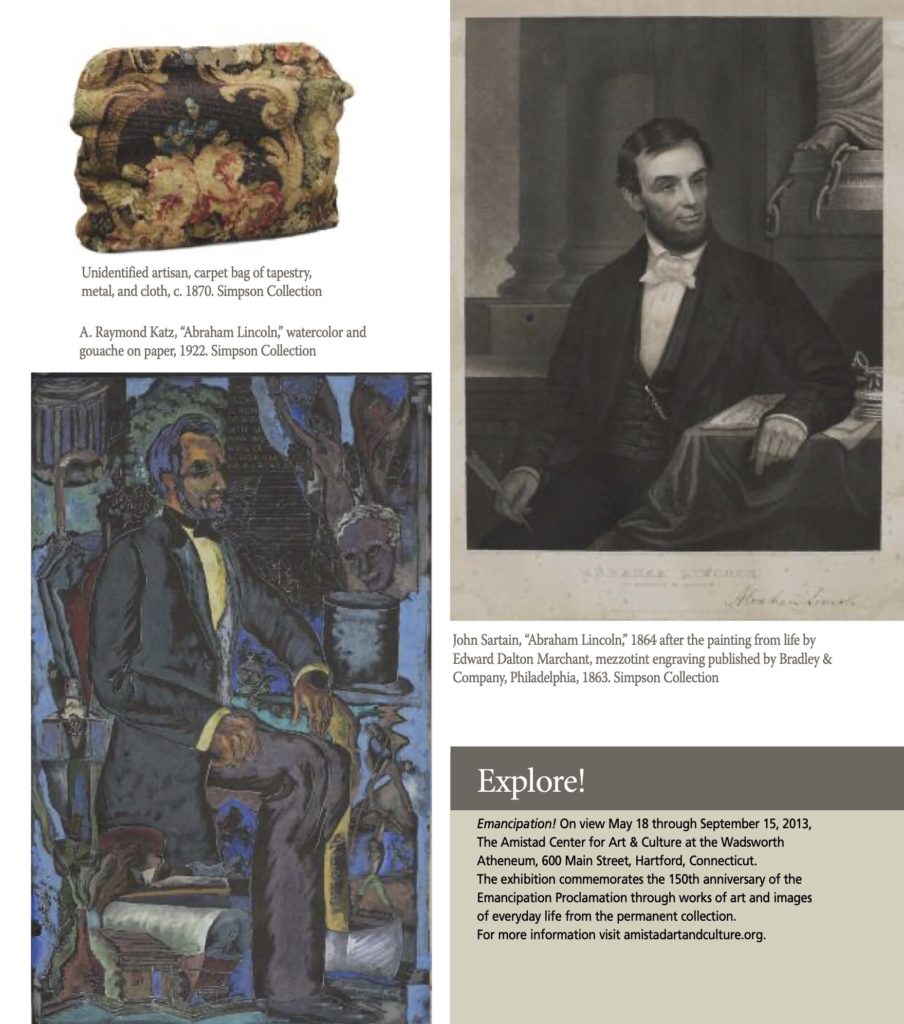

Disseminated in various souvenir forms, the image of Abraham Lincoln with the Emancipation Proclamation is the period’s most enduring symbol of freedom. Portrayals of Lincoln signing the document, reading it to others, or reflecting on it and on the pending revolution have magnified the sanctity of the document, which was, like so many political milestones, a compromise. Some Southern states had already seceded from the Union by March 1861 when Lincoln’s inauguration certified his presidency. The Civil War began the following month. The president made choices in order to preserve the Union and defeat the rebellious Southern states. Though not an abolitionist, he was morally opposed to slavery. Lincoln didn’t see the United States as a multi-racial nation, but he recognized the tactical benefit of ending slavery, which he knew would demoralize the South. His 1863 Emancipation Proclamation freed enslaved blacks in the states that had seceded. He was encouraged by Frederick Douglass, but also compelled by the demands of war, to authorize black men for military duty. As soldiers, some 200,000 black men—free born and previously enslaved alike—fought to end slavery and extendfreedom,whichdidbringsomethingnewforall.

Wm. Frank Mitchell is adjunct curator at The Amistad Center for Art & Culture.

Explore!

Read all of the stories from the Winter 2012-2013 Emancipation Proclamation issue

Read all of our stories about Connecticut in the Civil War on our TOPICS page