By Andrew W. Kahrl

(c) Connecticut Explored, Inc. Summer 2019

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

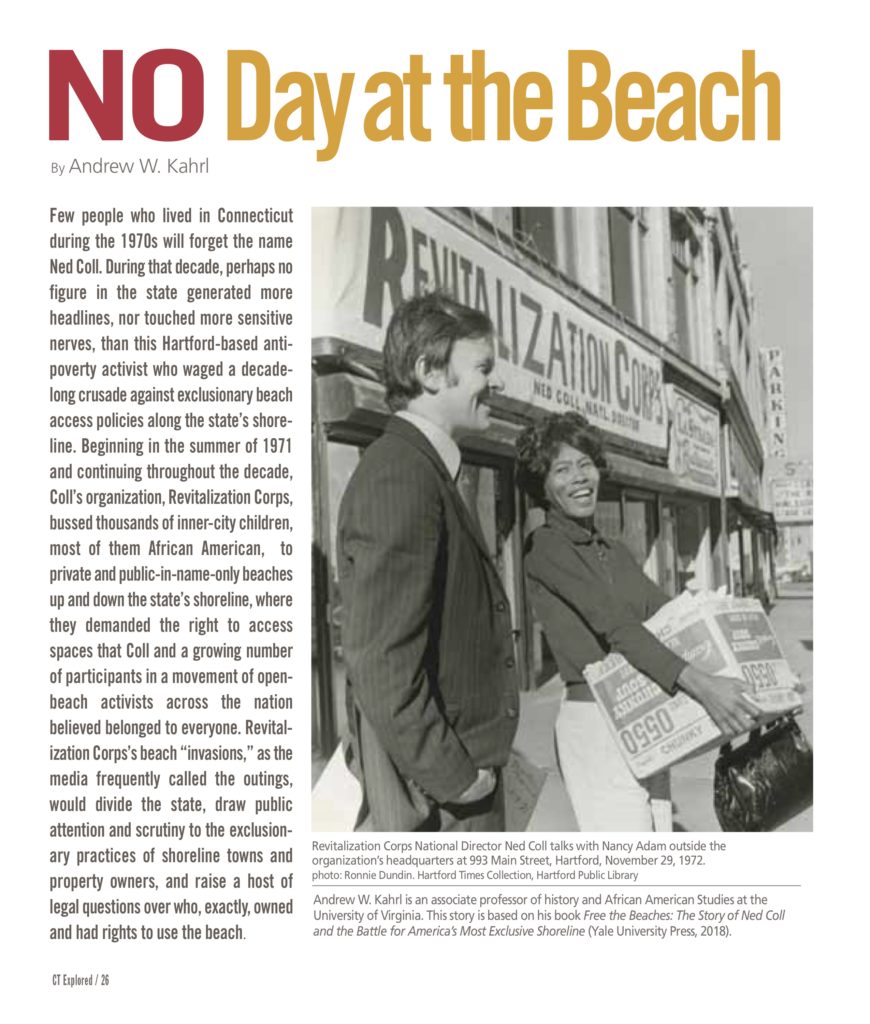

Few people who lived in Connecticut during the 1970s will forget the name Ned Coll. During that decade, perhaps no figure in the state generated more headlines, nor touched more sensitive nerves, than this Hartford-based anti-poverty activist who waged a decade-long crusade against exclusionary beach access policies along the state’s shoreline. Beginning in the summer of 1971 and continuing throughout the decade, Coll’s organization, Revitalization Corps, bused thousands of inner-city, most of them African American, children to private and public-in-name-only beaches up and down the state’s shoreline, where they demanded the right to access spaces that Coll and a growing number of participants in a movement of open-beach activists across the nation believed belonged to everyone. Revitalization Corps’s beach “invasions,” as the media frequently called the outings, would divide the state, draw public attention and scrutiny to the exclusionary practices of shoreline towns and property owners, and raise a host of legal questions over who, exactly, owned and had rights to use the beach.

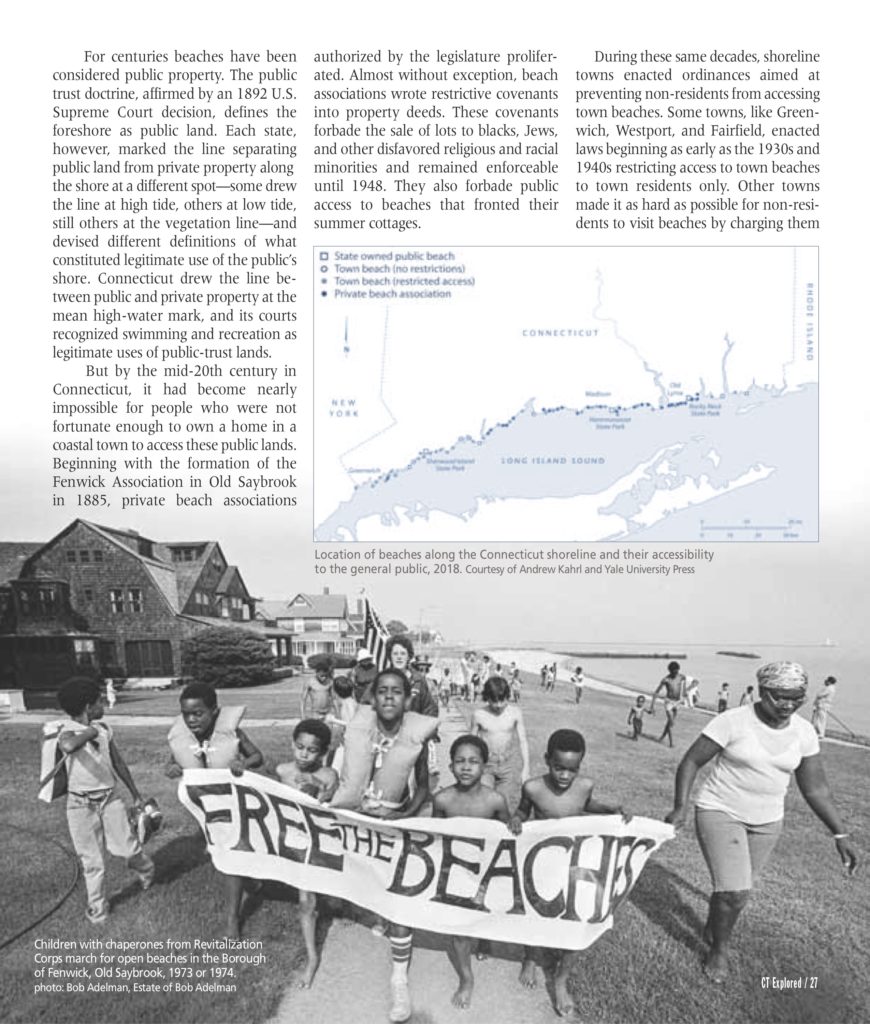

For centuries beaches have been considered public property. The public trust doctrine, affirmed by an 1892 U.S. Supreme Court decision, defines the foreshore as public land. Each state, however, marked the line separating public land from private property along the shore at a different spot—some drew the line at high tide, others at low tide, still others at the vegetation line—and devised different definitions of what constituted legitimate use of the public’s shore. Connecticut drew the line between public and private property at the mean high-water mark, and its courts recognized swimming and recreation as legitimate uses of public-trust lands.

But by the mid-20th century in Connecticut, it had become nearly impossible for people who were not fortunate enough to own a home in a coastal town to access these public lands. Beginning with the formation of the Fenwick Association in Old Saybrook in 1885, private beach associations authorized by the legislature proliferated. Almost without exception, beach associations wrote restrictive covenants into property deeds. These covenants forbade the sale of lots to blacks, Jews, and other disfavored religious and racial minorities and remained enforceable until 1948. They also forbade public access to beaches that fronted their summer cottages.

During these same decades, shoreline towns enacted ordinances aimed at preventing non-residents from accessing town beaches. Some towns, like Greenwich, Westport, and Fairfield, enacted laws beginning as early as the 1930s and 1940s restricting access to town beaches to town residents only. Other towns made it as hard as possible for non-residents to access beaches by charging them much higher access fees, making the process of buying beach passes hard for nonresidents, or reserving parking lots for residents. Not coincidentally, these same towns also enacted exclusionary zoning ordinances designed to prevent the poor and people of color from living there. By the 1960s, with the exception of three state beaches, nearly all of the state’s 253 miles of coastline were in private hands or effectively off-limits to the general public. And because racist housing policies and real estate industry practices prevented African Americans and Puerto Ricans from living in most shoreline towns, the shoreline became, in effect, for whites only.

Ned Coll might seem an unlikely person to challenge beach segregation. After graduating from Fairfield College in 1962, the Hartford native, whose father was a World War I veteran, Irish immigrant, and perennial Republican candidate for local office, returned home, took a job working for an insurance company, and began his climb up the corporate ladder. Then, in 1964, still distraught over the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, he abruptly quit his job and founded Revitalization Corps, a self-styled domestic Peace Corps dedicated, in his words, to waging a “war on apathy” among middle-class Americans. He was alarmed by what he saw in Hartford’s ghettos, but he was even more alarmed by whites’ indifference to these problems. The growth and prosperity of suburbs like West Hartford had given predominantly white residents distinct material advantages in the form of better schools, better housing, better services, better access to jobs, and the opportunity to build wealth. Prosperity also shielded them from seeing the reality of black disadvantage or having any meaningful interactions with black people. Hartford’s ghetto was a place they sped past on I-84, completed in 1969 and purposely designed to sever the black North End from the rest of the city.

Ned Coll might seem an unlikely person to challenge beach segregation. After graduating from Fairfield College in 1962, the Hartford native, whose father was a World War I veteran, Irish immigrant, and perennial Republican candidate for local office, returned home, took a job working for an insurance company, and began his climb up the corporate ladder. Then, in 1964, still distraught over the assassination of President John F. Kennedy, he abruptly quit his job and founded Revitalization Corps, a self-styled domestic Peace Corps dedicated, in his words, to waging a “war on apathy” among middle-class Americans. He was alarmed by what he saw in Hartford’s ghettos, but he was even more alarmed by whites’ indifference to these problems. The growth and prosperity of suburbs like West Hartford had given predominantly white residents distinct material advantages in the form of better schools, better housing, better services, better access to jobs, and the opportunity to build wealth. Prosperity also shielded them from seeing the reality of black disadvantage or having any meaningful interactions with black people. Hartford’s ghetto was a place they sped past on I-84, completed in 1969 and purposely designed to sever the black North End from the rest of the city.

Revitalization Corps’s programs ran the gamut from tutoring low-income children and helping young men and women find jobs to fighting slumlords and price-gouging merchants, from protesting austerity-minded politicians and indifferent bureaucrats to providing free lunches to hungry children and boxes of clothes to needy parents. The organization’s work was, as one of Coll’s former associates, Rob Carbonneau, described to me in 2016, “activism triage. …Everyday was like an adventure…. If you needed help, he was going to help you.” The idea took hold, and, within years, Revitalization Corps chapters formed in dozens of cities and college campuses across the country.

It was in that spirit that Coll launched a program aimed at getting children out of the sweltering city and down to the shore during the summer. The idea came in response to the demands of mothers and children for whom summer in the city was a time of tension, unrest, and fear, when the privileges of middle- and upper-class white Americans and the deprivations faced by ghettoized black and brown Americans were brought into sharp relief.

In the decades following World War II, as people, employers, and their taxes fled to the suburbs, cities struggled to maintain, much less expand, public recreation programs and facilities. Lacking access, residents of underserved, low-income urban neighborhoods sought relief from the summer heat by surreptitiously turning on fire hydrants—which activity became a flashpoint of conflict with police—or by playing along the banks of dangerous, often polluted urban waterfronts, which resulted in shocking numbers of drowning victims, most of them children, each summer, as The Hartford Courant reported throughout 1968 and 1969. In Hartford, a section of the city’s Park River that ran past the Charter Oak public housing project claimed the lives of seven children between 1942 and 1968. For years city officials ignored the pleas and organized protests of grieving parents to do something to address the crisis. On June 8, 1968 the Port Chester Daily Item reported that two African American children from Port Chester, New York, just over the Greenwich, Connecticut border, drowned while swimming in the Byram River. The incident occurred less than a mile away from Byram Beach, one of three public beaches in Greenwich at which lifeguards closely supervised swimmers.Despite its close proximity, Greenwich’s beaches were not an option for nonresidents.

Such tragedies fueled black unrest and played no small role in sparking urban uprisings during the long, hot summers of the 1960s. In its 1968 report on the causes of civil disorder in American cities, the Kerner Commission noted thatthe absence of safe, healthy, and attractive places for play ranked high among blacks’ grievances, just behind police brutality, unemployment, and inadequate schools.In Chicago, Detroit, and other cities, conflicts over recreational space, and over access to cooling waters on brutally hot summer days, provided the spark that lit large-scale uprisings.

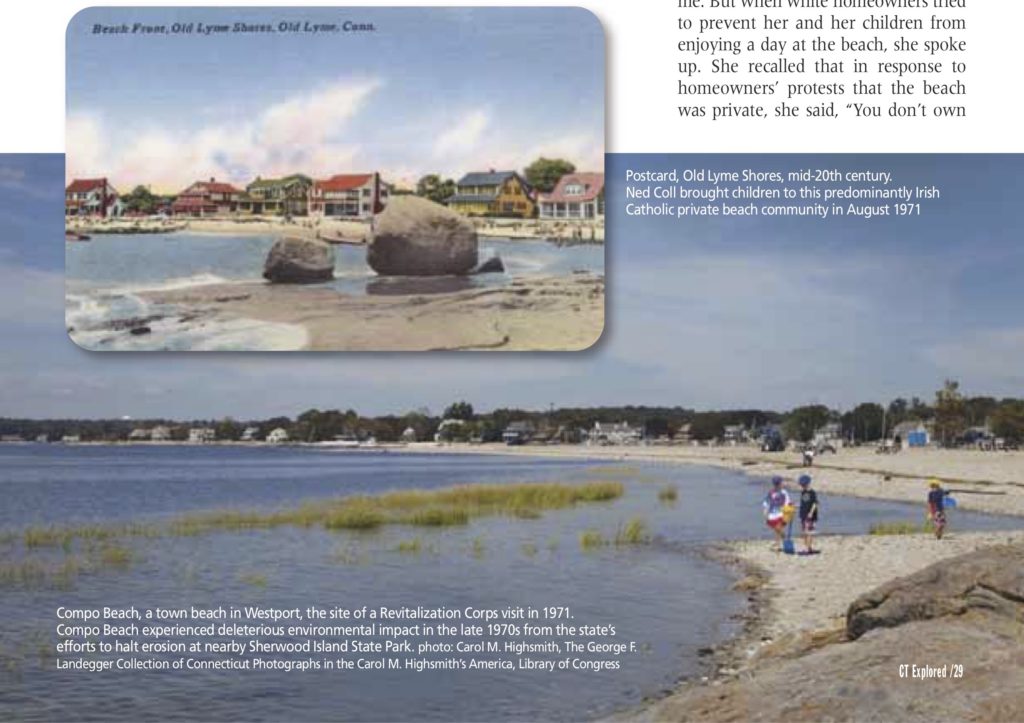

By bringing children and parents together in places such as the beach, Coll hoped to build bridges between the state’s white and black populations and, ultimately, to serve as a catalyst for social change. Instead, the busloads of children Coll brought to the shore were greeted by locked gates and orders to leave. Coll was shocked by the local reaction to these unannounced visits and incensed that these communities, which already had so much wealth and privilege, would not even allow urban children to enjoy a day at the beach that, he believed, rightfully belonged to everyone.

“It was amazing,” Tom Condon said in a 2009 interview with me about what he called one of the most remarkable stories he covered during the course of his 40-plus years as a reporter for The Hartford Courant. Coll “would show up at an all-white beach with a busload of black kids, [and say]‘here we are!’ And challenge anybody to throw them out.” “It was,” Condon remarked, “a bold and incredible kick in the teeth of the structural racism,” one that “forced people to think [not only]about racial segregation, economic segregation,” but also “the whole question of [whether it is]fair to give what is arguably a public resource and put it in private ownership.”

The excursions Coll organized revealed just how protective and exclusionary shoreline communities had become and the lengths to which they would go to keep outsiders off their beaches. Residents of wealthy towns like Old Lyme, Madison, and Greenwich came to dread the sight of a broken-down school bus—inflated rafts, tires, and row boats tied to its roof—loaded with children dressed in cut-off jeans and t-shirts, life jackets swung around their necks, their heads sticking out the windows, their faces filled with joy and expectation.

There was the rare unexpected ally. A mid-August 1971 visit to Old Lyme Shores, a predominantly Irish Catholic beach community known as highly exclusionary though not affluent, began with residents’ shouting at the unwelcome guests to leave. The police were called. That’s when Forry Laucks stepped off her porch and walked toward the beach. All of the children and Corps staff members, she told the officers, were her guests. Many of her neighbors were incensed, but Laucks stood her ground. As The New York Times reported on August 31, 1971, she could not understand “this big fear.” She simply wanted the children to enjoy a day at the beach. Slowly, other neighbors joined her in welcoming the children.

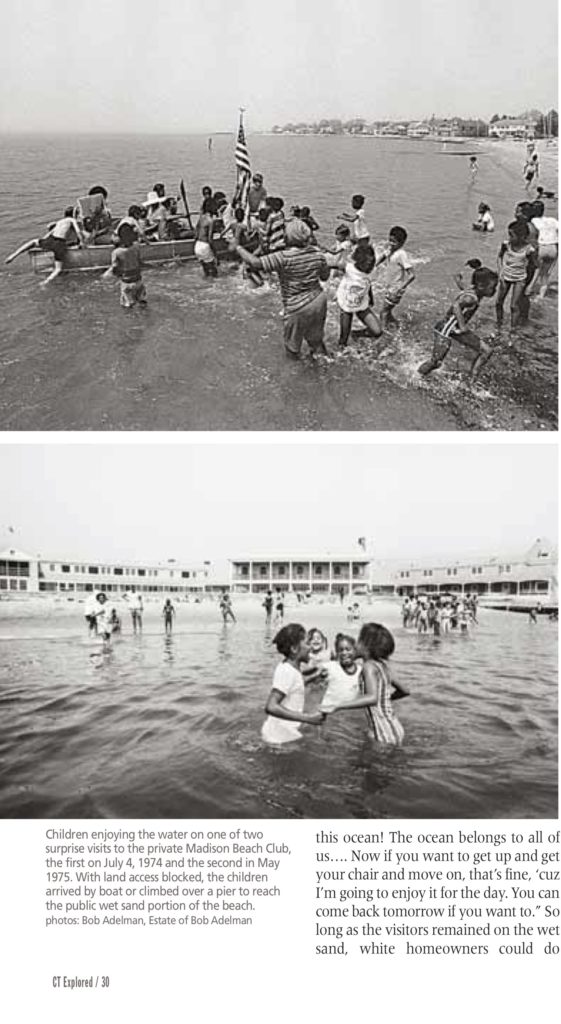

For many of the black and Puerto Rican mothers and children who went on these trips, it was not only their first trip to the beach but also their first direct confrontation with power. Earlie Powell, an African American mother and Corps volunteer from Hartford, had spent years cleaning white families’ homes and being mistreated by white bosses in silence, she said in a 2009 interview with me. But when white homeowners tried to prevent her and her children from enjoying a day at the beach, she spoke up. Sherecalled thatin response to homeowners’protests that the beach was private, she said, “You don’t own this ocean! The ocean belongs to all of us…. Now if you want to get up and get your chair and move on, that’s fine, ‘cuz I’m going to enjoy it for the day. You can come back tomorrow if you want to.” So long as thevisitorsremained on the wet sand, white homeowners could do nothing to stop them. They saw, as Coll (in a characteristic malapropism) put it, that “the emperor has no pants!”

A trip to the beach left an indelible impression on the children, as Lebert Lester’s experience illustrates,and for many, it marked their first introduction to racism. Lester, the owner of a barber shop and salon in Hartford when I interviewed him in 2009, recalled his experience as a young boy. During one of those trips to the beach, he was building sand castles with a blonde-haired, blue-eyed girl whose parents owned a summer cottage on the shore. He recalled that as they were digging a trench, the girl asked him, “how come I didn’t just wash off my skin. I looked at her like ‘what the heck is she talking about?’” Moments later, the girl’s father “grabb[ed]her by the hand” and told her it was time to leave. Still confused, Lester that eveningasked his parents what the girl meant, at which point his mother sat him down and “started explaining racism” for the first time.

From 1971 through the end of the decade, summers along the Connecticut shore were rife with tension and unrest, largely due to Coll’s activism. Local and, before long, national news reporters rushed to capture the drama. In November 1972 arsonists set fire to a cabin Revitalization Corps had rented for use as a camp the previous summer in Old Lyme. In the summer of 1973 two young female Revitalization Corps workers were assaulted at a motel near the Madison town beach that the organization had rented. One was slashed across the face with a shard of broken glass, The Courantreported (on June 13, 19, and 29, 1973). Coll was undeterred and Revitalization Corps’s beach demonstrations continued. The experienceled homeowners and local governments to adopt even more extreme mechanisms of exclusion, passing new ordinances and tightening existing ones, hiring more police and security, and mobilizing against any state or federal legislation perceived as threatening their local autonomy.

Local resistance to open beaches came at a price, one that we—and the beaches—are still paying today. While other coastal states took steps toward managed growth and protection of fragile coastal habitats, Connecticut’s unregulated development, privatization of public lands, and attendant environmental degradation of the shore continued unabated. The state’s environmental protection agency, in a report on the impacts of beach associations on coastal managements issued in 1976, identified a host of environmental problems resulting from uncoordinated real estate development among these hundreds of semi-autonomous private governing bodies, whose “parochialism and narrow interests” ran counter to efforts to implement a “comprehensive [coastal]management program” that treated “the coastline as an integrated whole.” Once-robust shellfish beds suffered from sharp declines in productivity, while the waters off several sections of the shore were contaminated by septic-tank leakage. In shoreline towns such as Madison, Old Lyme, Old Saybrook, Clinton, and Guilford, septic systems leaked dangerously high levels of sewage into Long Island Sound. It was, residents concluded, a small price to pay to prevent higher-density housing, which the lack of a wastewater system ensured. Despite pressure from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and numerous studies linking these septic tanks to water pollution in the Long Island Sound, many of these towns remain to this day steadfast in their opposition to public wastewater treatment. And despite the landmark Leydon v. Greenwich Connecticut Supreme Court decision in 2001 invalidating resident-only beach ordinances, in many respects the state’s shoreline remains as inaccessible as ever, as towns and property owners have found new (and old) ways to exclude the general public from the shore.

Health problems forced Coll to scale back his protest activity in the 1980s, but he remained an active presence in Hartford’s North End for years afterward. Though it’s been four decades since he led protests along the Connecticut shore, the issues Coll raised are just as relevant—perhaps more so—as they were then. Not just in the places where we live, but also the places we seek out for leisure and recreation, we remain a nation profoundly segregated along racial and class lines. Nowhere is this more apparent than along the nation’s shores, which have and continue to hold a mirror to the societies they surround.

Andrew Kahrl is an associate professor of history and African American Studies at the University of Virginia. This story is based on his book Free the Beaches: The Story of Ned Coll and the Battle for America’s Most Exclusive Shoreline (Yale University Press, 2018).