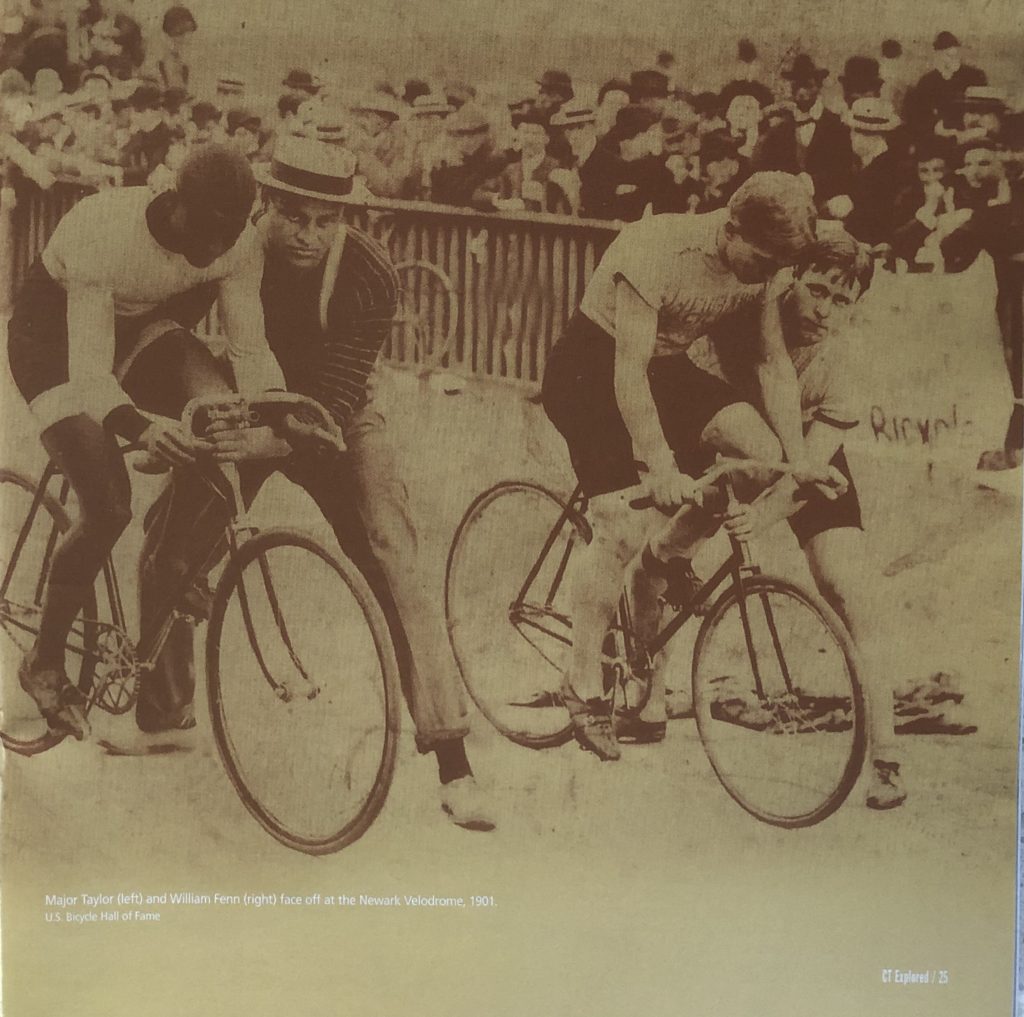

Major Taylor (left) and William Fenn (right) face off at the Newark Velodrome, 1901. US Bicycle Hall of Fame

By Bill Pierce

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Fall 2009

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

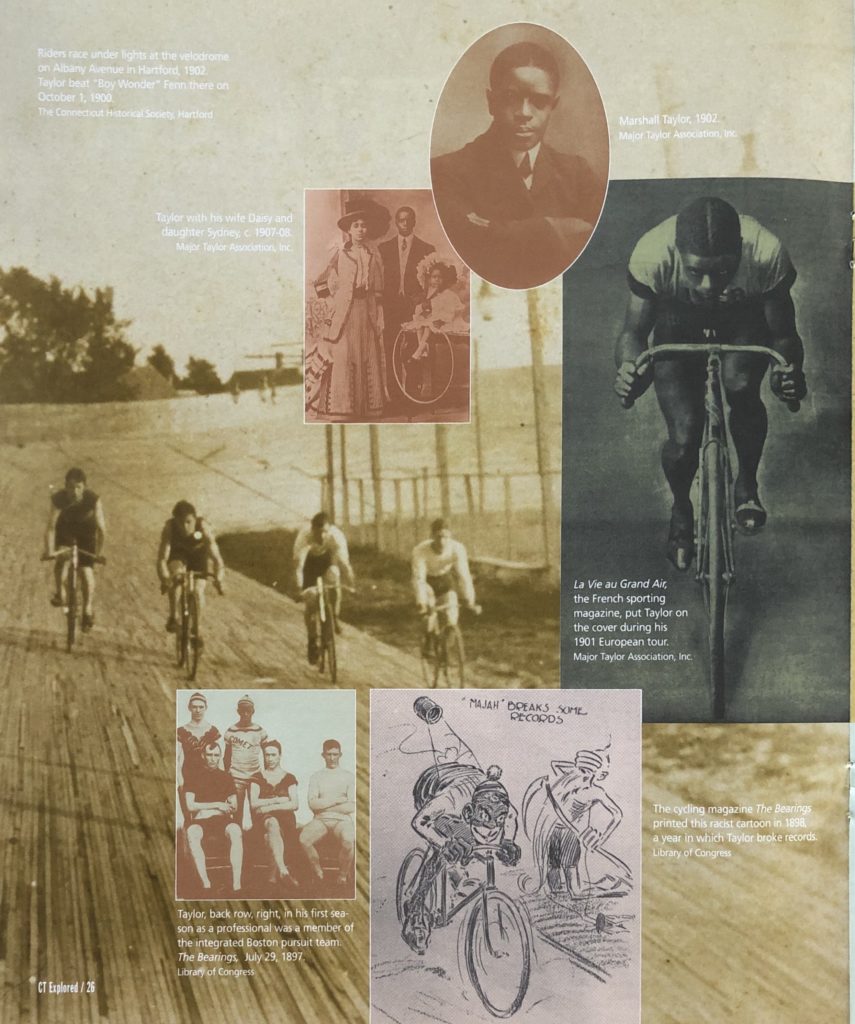

Monday, October 5, 1900 was a fair Hartford evening. The intersection of Blue Hills and Albany avenues glittered with the glare of incandescent bulbs as an audience of several thousand waited to watch a bicycle race between the local boy wonder William Fenn and the world champion Marshall Taylor — among the fastest men on two wheels in the country.

The race was held in the Hartford Velodrome, a one-sixth mile, oval, wooden track with steeply banked corners that had just opened that August. This velodrome was the second of three cycling tracks in the Hartford area: The first was a track used by both cyclists and horses at Luna Park in West Hartford, and the third was located just across the river in east Hartford’s Poli Field.

At the beginning of the 20th century, bicycle racing was, according to bike-race historian Peter Nye, the biggest sport in America, rivaled only by baseball. The League of American Wheelmen (LAW), a national membership organization for cyclists, had more than 75,000 members. Besides lobbying for paved streets and holding rallies in which hundreds of riders participated, the league sanctioned both amateur and professional races. Thousands of spectators filled bleachers at velodromes around the country to watch the best-paid athletes of the era. During a time when an automobile assembly-line worker was paid $2.50 a day, it wasn’t unusual for a professional cyclist to earn $50 a week and to have the opportunity to win large cash prizes. Because velodromes could contain both the action of competition and a paying crowd, racing took place primarily on their tracks. Competitive events included match races with mass starts, handicapped races where stronger riders started behind faster riders with less endurance, and, for added excitement, paced races.

Marshall “Major” Taylor, at 22, was the 1899 World Professional Cycling Champion, having won the premier one-mile event in front of a crowd of 18,000 in Montreal, Canada. William Fenn, a local 19-year-old who had recently won the American Amateur championship in Buffalo, New York, would challenge him in Hartford. While no pictures exist of their first race that October evening in Hartford, there is a photograph of the two men taken before the start of a 1901 Newark, New Jersey, competition. It shows both men perched on their bikes, each held steady by an assistant, their feet strapped to pedals. Although The Hartford Daily Courant described Fenn as “rugged,” he looks slighter than Taylor. Taylor holds his head higher as if staring determinedly down the track and seems the more confident of the two. While both bicycles look familiar – chain-driven track bikes with single rea cogs threaded directly to the back hub – they were different machines. The front wheel of Fenn’s bike was slightly smaller than the rear, and its handlebars flared outward. Taylor’s bike had equal-sized wheels and handlebars shaped like those used today.

The picture also shows another difference between the two: Marshall Taylor was Black. “Major” Taylor was, in the late 1800s, America’s only Black professional cyclist and a phenomenon of the time. Born in 1878, Taylor was one of eight children whose parents were former slaves living in Indianapolis, Illinois. According to Taylor’s 1928 autobiography The Fastest Bicycle Rider in the World, The Story of a Colored Boy’s Indomitable Courage and Success Against the Odds (Ayer Company, 1991 edition), his father was a Union Army Veteran and a coachman for a wealthy Indianapolis family. The young Taylor helped groom that family’s horses with his father. This introduced him to the family’s only son, Daniel, who was the same age. The two boys became friends, and according to Taylor’s autobiography, Daniel’s family employed Taylor to be Daniel’s “playmate and companion.” It was through Taylor’s relationship with the wealthy Daniel and his family that Taylor learned to ride a bicycle. He was soon the faster rider of the ground and developed extraordinary bicycle handling skills by learning acrobatic riding. Being with Daniel’s family, Taylor learned the “etiquette … dress … [and]mannerisms” of the late 19th century upper class. Yet Taylor also met, as he later wrote, “(my) bitterest foe … and one which I have never as yet been able to defeat … that dreadful monster prejudice,” when he was told that he could not use the YMCA with his friends.

After Daniel’s family moved to Chicago, leaving Taylor behind, Taylor took a job at an Indianapolis bicycle shop. He mostly performed menial tasks but would also perform acrobatic routines on his bicycle to attract customers. According to Taylor, it was the brass-button jacket he wore while doing these stunts that inspired the nickname “Major.”

Taylor rode in his first bicycle race before he was 14. The youngster was pitted against the best riders in the area and was not expected to finish the 10-mile event. Taylor won the race. Afterward he worked at another bicycle shop as an instructor and mechanic and continued to complete in local races. Taylor was 18 when he entered his first professional competition, a short sprint event preceding a grueling Madison Square Garden Six-Day Bicycle Race (a race in which the prize goes to the rider who covers the most miles over six days).

Racial prejudice dogged Taylor throughout his career. Early on he could not race on League of American Wheelmen-operated tracks because the league did not permit “Negroes to membership.” He had to be secretive about many events he rode in, “Because of a growing feeling against me on the part of the crack bicycle riders …because I was colored.” Once the young racer was surreptitiously brought by friends to the Indianapolis Velodrome, where Black riders were not allowed to ride, and he broke the one-fifth mile record set earlier in Paris. His life was frequently threatened, and competitors would make what he called “deliberate effort[s]” to make him crash. Eventually Taylor was allowed to race on league velodromes and in 1898 earned enough points through top-three finishes to become that year’s Champion of America. Yet as Taylor traveled across the country, he would often have to find lodging with Black families because the hotels and restaurants that served his white opponents would not serve him. He later decided to move to Worcester, Massachusetts because he noticed a lack of prejudice there and felt it was a place where he was treated in a “cordial manner.”

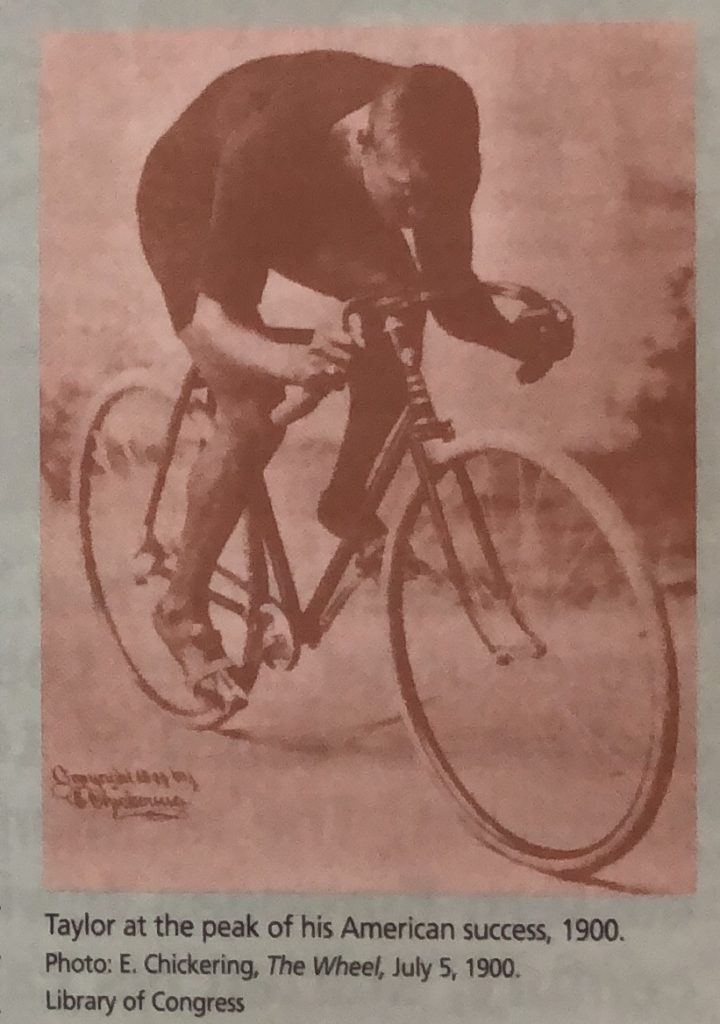

Despite the challenges he faced when off the track, during the closing years of the 19th century Taylor was a star of cycling. He set seven track records and earned the LAW and international championships. According to newspaper accounts in 1900, Taylor earned $25,000 during four years as a professional racing cyclist. At a time when professional athletes were known for being rough, Taylor was known for his sportsmanship and commitment to his faith. In 1898 he was among the professional riders who joined the National Cycling Association (NCA) when he was assured he would not have to race on Sunday. However, at the end of the 1898 season and despite being a few points away from winning the NCA Professional Championship, he decided to skip the penultimate race because it was held on a Sunday. He forfeited any chance of securing the championship and was nearly banned from competing with the NCA. Taylor felt the NCA was scheduling the race on a Sunday in an attempt to remove him without overtly naming race as the reason. Taylor included in his autobiography the NCA Board of Appeals decision to allow his reinstatement:

Despite the challenges he faced when off the track, during the closing years of the 19th century Taylor was a star of cycling. He set seven track records and earned the LAW and international championships. According to newspaper accounts in 1900, Taylor earned $25,000 during four years as a professional racing cyclist. At a time when professional athletes were known for being rough, Taylor was known for his sportsmanship and commitment to his faith. In 1898 he was among the professional riders who joined the National Cycling Association (NCA) when he was assured he would not have to race on Sunday. However, at the end of the 1898 season and despite being a few points away from winning the NCA Professional Championship, he decided to skip the penultimate race because it was held on a Sunday. He forfeited any chance of securing the championship and was nearly banned from competing with the NCA. Taylor felt the NCA was scheduling the race on a Sunday in an attempt to remove him without overtly naming race as the reason. Taylor included in his autobiography the NCA Board of Appeals decision to allow his reinstatement:

The riders have drawn the color line, which is unconstitutional, un-American and un-sportsmanlike. It is wrong in the abstract, unrighteous in the concrete and indefensible … the color line will not be accepted by the American public … He [Taylor] is here in flesh and blood and must be delt with as a human being … entitled to every human right …

There was another reason for Taylor’s reinstatement. Taylor had public sentiments behind him, and race promoters felt the public should continue to enjoy, as his biographer Andrew Ritchie put in his 1928 Major Taylor, The Extraordinary Career of a Champion Bicycle Rider (Ayer Company, 1991 edition) the “young David” who took on “several Goliaths at once.”

Who Was William Fenn?

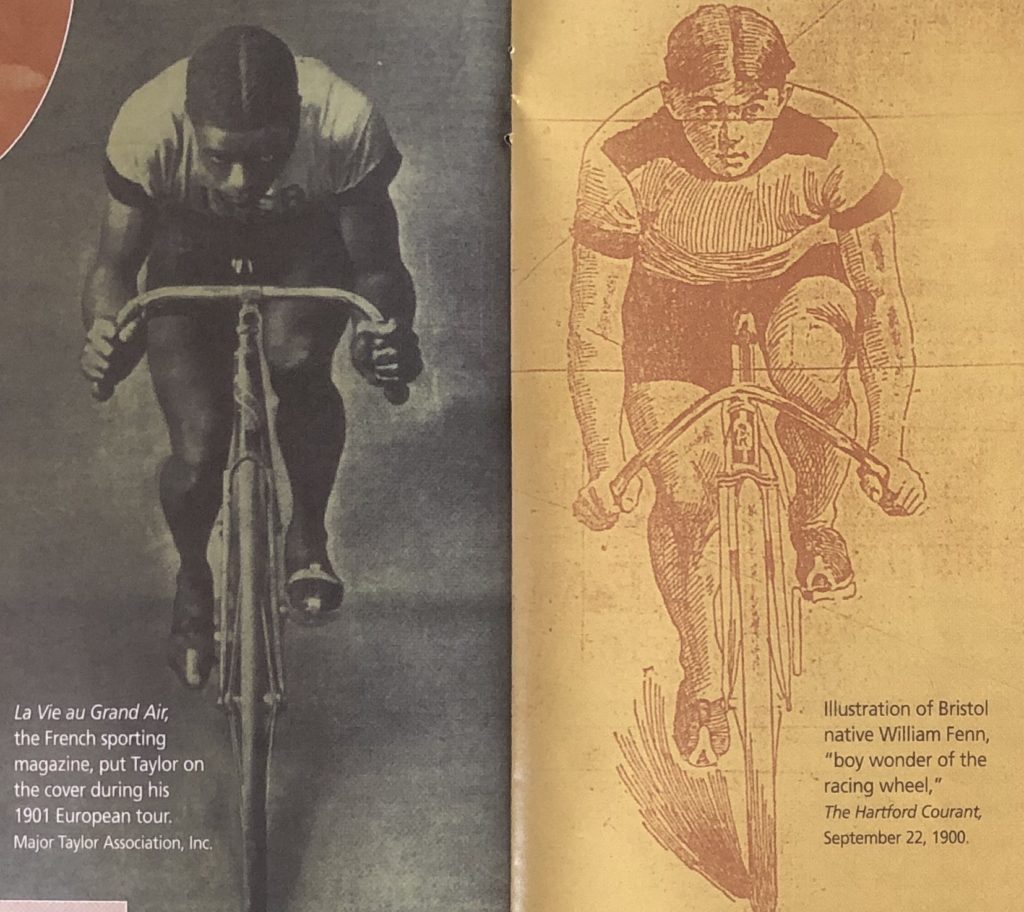

While Taylor’s life is chronicled in several books, William Fenn’s story is barely documented. Known by his nickname Willie, Fenn was probably born around 1881 and grew up in the Forestville section of Bristol, Connecticut. According to a undated article published around September 1900 in the The Hartford Daily Courant, Fenn began riding a bicycle when he was eight years old. His father owned a blacksmith shop that did fording work for local factories, and Fenn worked “at the anvil.” His first race was a Bristol road race in 1898 in which he finished fifth. Fenn went on to race on bicycle tracks in Waterbury, New Haven, and Hartford. By 1900, Fenn had not only won the Amateur American Championship, he held world records for one-third- and two-third-mile distances and the state record for the paced mile, which he set in Hartford by riding the distance in a minute and 39 seconds (or 37 miles per hour). Taylor’s world record at the time for a paced mile was a minute 31 and 4/5 seconds. Fenn went on to a successful professional career, though he never achieved the fame Taylor did. He later raced Taylor a number of times and was paired with him for a race on a tandem bicycle. Fenn left Connecticut, moved to East Orange, New Jersey, and raised a son, William Fenn, Jr., who was a cycling track star and Olympic competitor.

Taylor and Fenn Face Off in Hartford

(left) Major Taylor on the cover of “Le Vie au Grand Air,” the French sporting magazine, 1901. Major Taylor Association Inc.; right: Illustration of Bristol, Connecticut native William Fenn, “boy wonder of the racing wheel,” The Hartford Courant, September 22, 1900

The Hartford race between Taylor and Fenn in October 1900 was billed as a “Championship Race.” Taylor noted in his autobiography that he was reluctant to race Fenn because he felt a loss to an amateur would mean the probable end to his racing career. On the other hand, Taylor respected Fenn and felt their race would be one of the “most fiercely contested events on American track.” The Hartford Times touted Fenn as a strong match for Taylor, reporting on October 4, “those who have seen Fenn in training these past few days are not so positive that the colored wonder will have an easy proposition.” The Hartford track, after all, was on Fenn’s home turf.

Taylor and Fenn’s championship race was a prologue to an evening of exciting competitions including a 25-mile amateur championship race in which Fenn would also compete. In 1900, betting was an integral part of the sporting scene, and bicycle races, with their speed, tactics, and danger were exciting events on which to place wagers. Betting was an added attraction for Hartford-area spectators, many of them workers from local manufactures such as Royal, Underwood, Colt, and Pope and employees of the publishing and insurance industries that made Hartford the richest city in the United States after the Civil War. Spectators that evening were probably almost exclusively white. Although Hartford had a population of more than 79,000 in 1900, fewer than 2,000 of the city’s residents were black, and most of those held low-paying jobs as laborers.

Though Taylor’s autobiography and news accounts differ in some of the details, the race between Fenn and Taylor apparently went something like this: Fenn appeared “a trifle nervous” when he came onto the track and was greeted with applause. Taylor was described as looking “as though he had some business to attend to and was in a hurry to finish it.” The race started with a crack of the starter’s pistol, and the murmuring crowed changed to a screaming throng. The two racers circled the track, riding close together. Although Taylor was known to have a fast start, Fenn led all the way. Taylor recalled how he allowed Fenn to “take the pace,” that is, be in the position closest to the pacemaker (a cyclist from New Britain). During the final lap, as they approached the finish line, Taylor “jumped” and finished first by “several lengths.” According to The Hartford Times, their first contest lasted 2 minutes and 20 3/5th seconds. But Fenn was not satisfied. He protested (though not formally), telling officials he was fouled by Taylor, who he said “rode him too close on the corner.”

Track racing was a brutal sport, and no one knew that better than Taylor. But it was in Hartford that for the first time Taylor had to re-ride a race due to a protest.

While Fenn was a strong and capable rider, Taylor was the seasoned professional who understood how to use psychology to his advantage. At the start of the re-match, Taylor jumped and caught the pacer. Under the watchful eye of the judges, Taylor rode ahead of Fenn until the end of the fifth lap. Then Fenn sprinted ahead of Taylor. With the race so close to the finish, Fenn’s fans anticipated victory. Fenn was reported to be strong enough “to ride the last lap of a race as fast as the first one — top speed.” But 25 yards from the finish, Taylor jumped forward and won the race by several feet, with a time of 2 minutes and 25 seconds.

Taylor’s cycling career was one of the great stories of the early years of the last century. In 1900 he scored the highest number of points in the NCA championship sprint series, double the score of the second place rider. But the following season turned difficult as his opponents united to thwart his success. Using tactics such as “pocketing,” riders would group around Taylor to prevent his breaking into a sprint. One faction of riders was unrelenting in subjecting Taylor racist words and actions. Taylor’s riding became erratic; he lost races he should have won. Taylor was also challenged by up-and-coming riders, including the now-professional Fenn and Frank Kramer, a rider who is now considered the best cyclist of his era. Kramer won the 1901 American championship with 72 points to Taylor’s 64.

Even as he considered retirement, Taylor used his membership in the International Cycling Union (which today continues to govern international cycle racing) to race in Europe and then Australia, where biographer Ritchie says he was “royally received” as a cycling star in Paris, Berlin, Milan, and Sydney. But he could not escape that monster, racism. In Paris in 1907, fellow Americans staying at the same hotel threatened to leave if he wasn’t removed.

Taylor’s Other Tie to Hartford

In 1904, when Taylor was 25, he took a break from racing. By 1905 his friends saw how the athlete had pushed himself to his limits. As a professional in a highly competitive sport, Taylor himself knew his legs would not endure. But he now had a family in Worcester to support. He had married Daisy Morris of Hudson, New York, in Ansonia, Connecticut, on March 21, 1902. At the time they met, she was the ward of her uncle, the Reverend Louis Taylor, an African Methodist Episcopal Zion Minister with a congregation in Hartford. In 1904, the couple went to Australia, where Daisy gave birth to their only child. Taylor had decided his son would be a champion cyclist, too, and thought having the child in Sydney, where Taylor had known great success, would be propitious. As Ritchie recounts, when the baby was born, on October 11, 1904, Taylor asked the doctor if his child was “perfectly developed.” The doctor replied “quite soberly. ‘This child can never be the great sprinter you are.’ ‘Why doctor?’ ‘Because it is a girl.’”

Taylor returned to racing for five more seasons before retiring in 1910. From then on, his life was a mixture of successes and setbacks. One of the richest men in Worcester, he was a celebrity who would greet famous visitors and drive them in his automobile, one of the first private vehicles in the city. He invented an adjustable handlebar stem for track bicycles that is still being used. Unfortunately, a combination of bad investment, and a tendency to live beyond his means led Taylor to sell his property and even his wife’s jewelry. Daisy worked as a seamstress to pay for their daughter Sydney’s college expenses and to help make ends meet. In 1926, a Worcester Evening Gazette story about Taylor’s fall from fortune spurred donations from well-wishers totaling $1,200. Taylor published his autobiography in 1928 in an effort to “use the story of his life as an example to other blacks in their struggle to achieve equality in a racist society.”

Taylor and Daisy separated in 1930, and he spend the next two years traveling from city to city selling his book. He died on June 12, 1932, in the charity ward of Chicago’s Cook County Hospital. Taylor’s death made front-page news in the city’s Black newspaper, but his wife and daughter and his brother and sister didn’t learn about his death until later, when someone sent a copy of the paper to his son-in-law. Because Taylor’s body wasn’t claimed, it was buried in a simple wooden box in a pauper’s grave in a remote Chicago cemetery. Although his death was barely noted in the mainstream press, a French weekly sports magazine, in recognition of “le negre volant” who had won more than 100 races in France, published an article on his life and passing.

Taylor and Daisy separated in 1930, and he spend the next two years traveling from city to city selling his book. He died on June 12, 1932, in the charity ward of Chicago’s Cook County Hospital. Taylor’s death made front-page news in the city’s Black newspaper, but his wife and daughter and his brother and sister didn’t learn about his death until later, when someone sent a copy of the paper to his son-in-law. Because Taylor’s body wasn’t claimed, it was buried in a simple wooden box in a pauper’s grave in a remote Chicago cemetery. Although his death was barely noted in the mainstream press, a French weekly sports magazine, in recognition of “le negre volant” who had won more than 100 races in France, published an article on his life and passing.

In 1948, a group of former professional cyclists from the Chicago area called the Bicycle Racing stars of the Nineteenth Century learned about Taylor’s death and burial. They contacted Frank Schwinn of the Schwinn Bicycle Company and asked if he would help move the body to a better location. Schwinn agreed, and Taylor’s body was moved to the Memorial Garden of the Good Shepard in Chicago, where a memorial was erected in his honor. The inscription reads “World champion bicycle racer who came up the hard way without hatred in his heart, an honest, courageous and God-fearing, clean-living gentlemanly athlete…who always gave out his best.” Many aging former competitors and black athletes attended a ceremony marking Taylor’s reburial, including Ralph Metcalf, who broke world track records in 1932.

Over the last few years, Taylor’s legacy has grown. In 1982, Indianapolis opened the Major Taylor Velodrome. A television movie about his, Tracks of Glory, was produced in 1991, and on May 21, 2008, the city of Worcester dedicated a statue to his memory at a ceremony featuring three-time Tour De France winner Greg Lemond and three-time Olympic gold medalist Edwin Moses. Moses, who serves as honorary chairmen of the Major Taylor Association (which worked with the city of Worcester to have the memorial built), noted during the ceremony that Taylor was “a man truly before his time…who was able to overcome all the odds…becoming a world champion.”

Bill Pierce is a former competitive cyclist who first learned of Major Taylor in the 1970s when he heard a cyclist from Australia remark how another rider rode like “the Major.”

Explore!

Find more stories about African Americans in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

Find more stories about Sports in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.