By Andy King

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Ivoryton laborers spent their days at factories owned by Comstock, Cheney & Company, and Pratt, Read & Company, cutting wood, bleaching ivory, and assembling piano actions. By the 1940s, employees had begun building military gliders, using innovation and grit to help the company survive amidst the decline in piano production.

The industrial village of Ivoryton developed in Essex in the 1800s after shipbuilding declined in the Connecticut River Valley. European settlers established Essex in the Saybrook Colony in 1648, in the Nehantic (Niantic) lands known as Potapaug. The town became known for its productivity and enterprise. Wealthy sea captains profited from the area’s easy access to Long Island Sound and the work of both free and enslaved laborers at ropewalks, shipyards, and smithies. Over time, as ships grew, the Connecticut River’s shallow water limited trade, but the local coves and rivers provided a power source for mills.

The industrial village of Ivoryton developed in Essex in the 1800s after shipbuilding declined in the Connecticut River Valley. European settlers established Essex in the Saybrook Colony in 1648, in the Nehantic (Niantic) lands known as Potapaug. The town became known for its productivity and enterprise. Wealthy sea captains profited from the area’s easy access to Long Island Sound and the work of both free and enslaved laborers at ropewalks, shipyards, and smithies. Over time, as ships grew, the Connecticut River’s shallow water limited trade, but the local coves and rivers provided a power source for mills.

According to Follow the Falls: Ivoryton (Overabove, 2023), in 1799, Essex silversmith Phineas Pratt received a patent for a circular saw used to cut fine-tooth combs. Pratt’s invention saved time and labor, and soon, the technique was applied to shaping other ivory products. (Local traders’ complicity in the enslavement of central Africans and the hunting of elephants ensured ready access to ivory.) Meanwhile, the mass production of luxury goods became a mainstay of Connecticut River Valley firms like Pratt, Read and Comstock, Cheney. Eventually, manufacturers specialized in ivory veneers for piano keys and, soon after, wooden piano actions, the complex mechanisms behind the keys that hammer strings and create the classic piano sound. Ivory and piano production filled Ivoryton with factory workers and their families. American piano sales peaked in the 1910s, but new methods of listening to music at home emerged soon after, and the Great Depression tightened wallets. Production declined, and in 1936, Pratt, Read and Comstock, Cheney merged.

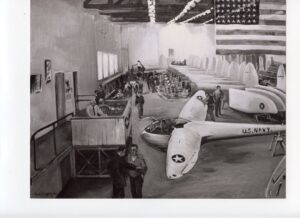

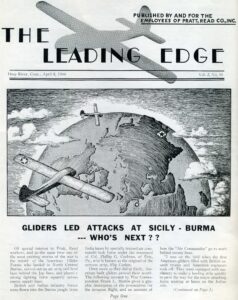

The new Pratt, Read & Company experienced a revival during World War II, contracting with the US government to produce military gliders. The navy was not interested in the company’s experience processing ivory but in its storage, skilled laborers, and specialized equipment for the wooden piano actions, which could be adapted for the wooden gliders. The company built about 100 two-person Pratt-Read PR-G1 gliders to train military pilots and about 1,000 Waco CG-4A gliders, using designs from the Waco Aircraft Company. Pratt, Read manufactured the gliders, assembled them, took them apart, packaged them, and shipped them by truck to Old Saybrook and then by train to the military. The gliders saw wartime action in Sicily, Burma, Normandy, and Holland.

The new Pratt, Read & Company experienced a revival during World War II, contracting with the US government to produce military gliders. The navy was not interested in the company’s experience processing ivory but in its storage, skilled laborers, and specialized equipment for the wooden piano actions, which could be adapted for the wooden gliders. The company built about 100 two-person Pratt-Read PR-G1 gliders to train military pilots and about 1,000 Waco CG-4A gliders, using designs from the Waco Aircraft Company. Pratt, Read manufactured the gliders, assembled them, took them apart, packaged them, and shipped them by truck to Old Saybrook and then by train to the military. The gliders saw wartime action in Sicily, Burma, Normandy, and Holland.

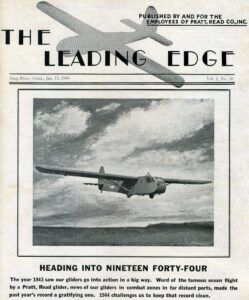

The Leading Edge, a newsletter published by Pratt, Read between 1942 and 1944, updated employees on the war, reporting times when the company’s gliders helped America soar to victory. The Leading Edge also provides insight into wartime military production and ivory processing. According to Edith DeForest, Robbi Storms, and former Essex town historian Don Malcarne in Deep River and Ivoryton (Arcadia Publishing, 2002), women worked in bleaching houses. They were called “matching girls,” referring to their task of “matching” pieces of ivory according to different shades of white. Once the company started to produce gliders, women worked alongside men in various departments, from inspection to final assembly.

The Leading Edge, a newsletter published by Pratt, Read between 1942 and 1944, updated employees on the war, reporting times when the company’s gliders helped America soar to victory. The Leading Edge also provides insight into wartime military production and ivory processing. According to Edith DeForest, Robbi Storms, and former Essex town historian Don Malcarne in Deep River and Ivoryton (Arcadia Publishing, 2002), women worked in bleaching houses. They were called “matching girls,” referring to their task of “matching” pieces of ivory according to different shades of white. Once the company started to produce gliders, women worked alongside men in various departments, from inspection to final assembly.

According to Follow the Falls, Ivoryton, Pratt, Read built over 14,000 gliders during World War II, but the government-contracted work failed to resurrect the company wholly. The military suspended the glider program in 1953, and Pratt, Read moved on to manufacturing helicopter blades during the Korean War. When the ivory trade was largely banned in the 1950s, Pratt, Read adapted by producing plastic veneers for pianos and organs, although national piano production continued to decline. After much of its factory, equipment, and inventory was destroyed by a major flood in 1982, Pratt, Read ended production in Ivoryton and moved most operations to its other location in South Carolina. According to Essex Historical Society interviews with Comstock descendant Woody Comstock, after repairing flood damage, the company resumed small-scale piano-related production in Ivoryton. However, by 2010, Comstock sold the company, and Ivoryton production ceased.

The companies that helped establish Ivoryton no longer thrive there as they did in the industrial era. Today, the village’s only connection to ivory comes through the iconic elephant imagery that appears throughout the town in a nod to its industrial past. For a brief time, though, glider manufacturing for the US military supported the riverside village’s economy and workforce.

Andy King is the membership and programs coordinator at Essex Historical Society and a museum interpreter for Connecticut Landmarks.

Learn More!

Christopher Pagliuco, “Ivoryton,” Connecticut Explored, Fall 2008, ctexplored.org/ivoryton

Essex Historical Society and Essex Land Trust, Follow the Falls, www.essexhistory.org/follow-the-fall