By Brittney Yancy and Beth Burgess

On November 1, 1943 the Hartford Times published “Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Maid Visits Home,” an interview between journalist George Birney Jr. and long-time Hartford resident Ida Holmes Braxton (1869-1951), a Black woman reformer who began her career in 1885 at Nook Farm as the maid of celebrated anti-slavery writer Harriet Beecher Stowe. Birney wrote, “Mrs. Ida L. Braxton has the distinction of being one of the few people living in Hartford who can remember Harriet Beecher Stowe and other distinguished residents of ‘The Hill’ in the last decade of the 19th century.” While the story of Ida Braxton, like that of many African American women reformers, remains a fragmented mystery, poring over documents from the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center and Hartford History Center unveils a fuller narrative that goes beyond the still snapshot of Braxton’s work at Nook Farm.

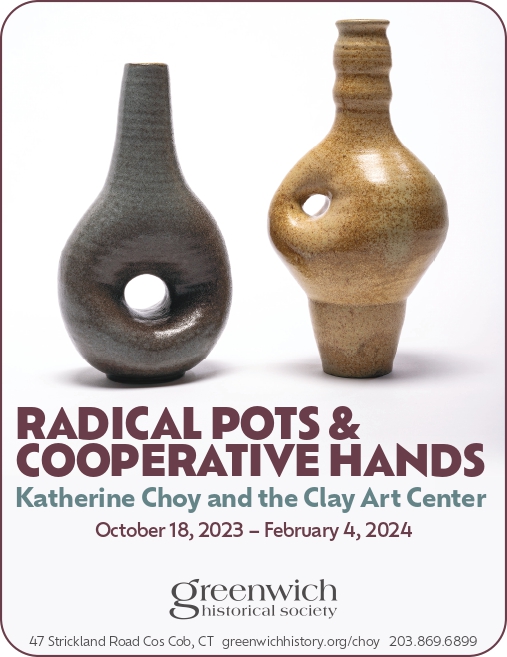

Ida Braxton’s niece, Anna Booze, and

Braxton visit with Katharine Seymour Day

and reflect on their days at Nook Farm as

they admire a bust of Harriet Beecher

Stowe, 1943.

photo: Courtesy of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center

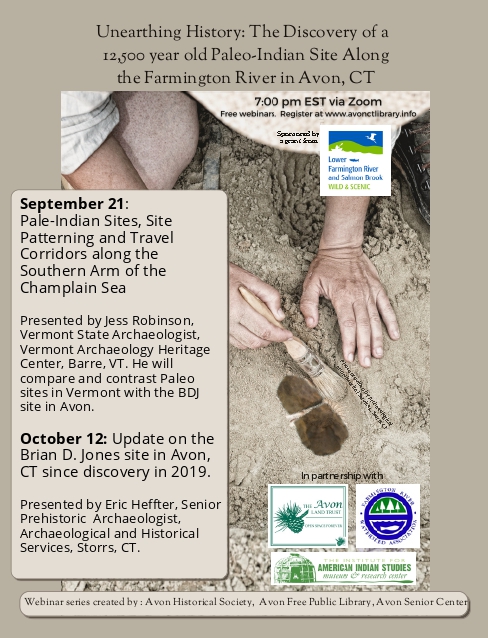

“Colored Women To Build Home,”

The Hartford Courant, March 6, 1918

Born in Caroline County, Virginia in 1869, Ida Holmes grew up with her mother Ellen Howard and siblings Joseph, Fannie, and Daniel on the plantation of Judy Calanda. The decades after the Civil War promised an era of hope and freedom for African Americans; however, the failure of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow forced African Americans like Ida to seek refuge and a new life in the North. Thousands of African Americans from North Carolina, Georgia, and Virginia called Hartford, New Haven, and Norwich home by the 1870s. Historian Stacey Close, in his chapter “Connecticut and the Aftermath of the Civil War” in African American Connecticut Explored (Wesleyan University Press, 2014), states, “In 1871, for instance, a group of African Americans from Virginia came to Connecticut in hopes of finding better economic opportunity and religious freedom in Connecticut.” The history of the Holmes family is unknown, but Ida recalled in Birney’s article that “it was through an aunt, a maid in the [Rev. Joseph] Twichell home, that she came to Hartford.” Teenage Holmes left Caroline County and settled in Hartford by 1885.

Holmes belongs to the generation of African American women who worked as household workers at the end of the 19th and turn of the 20th centuries. She began working as Harriet Beecher Stowe’s maid in 1885. Little is known about Ida’s six-year career at Nook Farm, but in her interview with George Birney she recalled how Stowe was an ally of the African American community. She said, “Mrs. Stowe was the sweetest woman to walk the earth. She was a sweet, good darling.” In 1891, at 22, Ida Holmes married Virginia migrant and coachman Moses Braxton and ended her short stint with Stowe. Ida became a housewife and, like many Black domestics, became an entrepreneur by opening a laundry service.

By 1900 the Braxtons and Ida’s mother had moved to Liberty Street in the center of the Clay-Arsenal neighborhood in Hartford’s North End. According to the Hartford Black History Project, Inc.’s website, the Clay-Arsenal neighborhood targeted “the first wave of southern migration [the 1880s]…it grew to include the early [Black] settlement near Mather Street and what had been called, according to Gurdon W. Russell, in his 1890 article “Up Neck in 1825,” Maps and Charts: Finding Your Place in Connecticut History, Connecticut Historical Society Collection, ‘Nigger Lane.’” Despite the blatant white supremacy and economic instability surrounding them, the Braxtons lived in small Black middle-class enclaves featuring Black-owned businesses, restaurants, salons, barbershops, and tailors. Like most Black communities of the time, the cornerstone of the Clay-Arsenal neighborhood was its Black churches–Talcott Street Church (now Faith Congregational Church), Union Baptist Church, Shiloh Baptist Church, and Bethel AME Church. The Braxton family were prominent members of Union Baptist Church, which according to its website was the home parish to Black migrants from Essex County, Virginia.

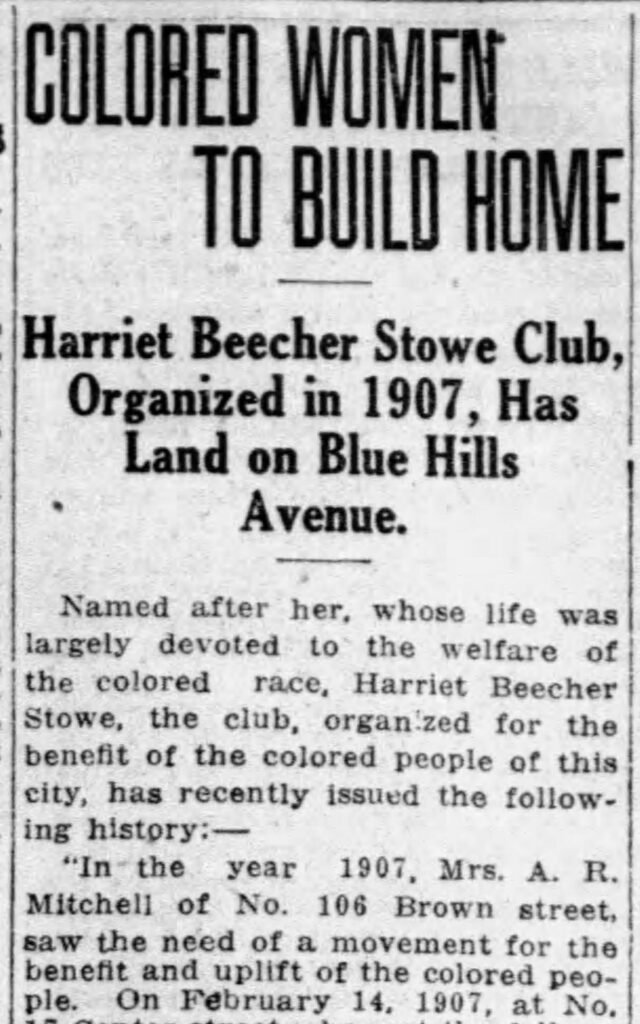

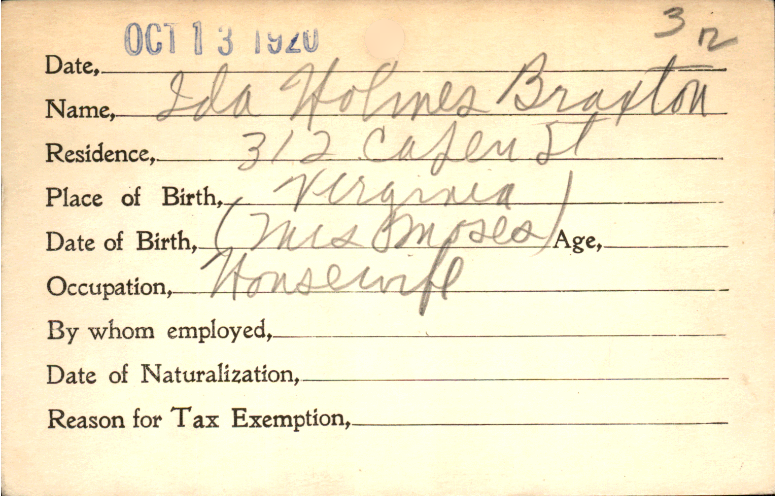

Voter registration card of Ida Holmes Braxton, October 13,

1920. photo: Courtesy of Hartford History Center, Hartford Public Library

Braxton was deeply immersed in Black Baptist tradition and practiced a woman-centered faith that encouraged women to be active agents in uplifting the race. Applying the “lifting as we climb” approach to her religious activism, Ida rose to the front line of the Black-women’s club movement in Hartford. The Black women’s club movement confronted similar issues as their white counterparts–education, suffrage, health, and temperance. However, this national reform movement also combated racism and misogyny and gave Black women access to political power and social reform. In 1896, the year of Stowe’s death, hundreds of Black club women–Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Mary Church Terrell, and Harriet Tubman– met in Washington, D.C., to form the largest African American political organization of the time, the National Association of Colored Women Clubs (NACWOC). The first Connecticut club under the Northeastern Federation of the NACW was the Rose of New England League, formed in Norwich in 1897. The Black women’s club movement arrived in Hartford with the formation of the Harriet Beecher Stowe Club (HBSC) on February 14, 1907.

Under the leadership of Hartford reformers Mrs. A.R. Mitchell, Sadie Jacklyn, Margaret Holden, and Fannie Carroll, Braxton joined the HBSC with the purpose of racial uplift and advocating for social reform. On March 6, 1918, The Hartford Courant quoted Margaret Holden, the HBSC secretary, as saying, “the club is named after one of the greatest women ever to live and a friend of the colored race.” In her Hartford Times interview, Braxton recalled that Stowe had formed an allyship with local African American women in her final years. Stowe hosted an open house every Thursday in the last decade of her life, Braxton said, adding that “she would have us at her home for [a]luncheon and entertained us for the afternoon. She would sing and play the piano for us.”

The HBSC upheld a multi-issue agenda centered on racial uplift, social welfare, education, employment, anti-lynching legislation, and suffrage. According to The Hartford Courant’s March 6, 1918 article, the HBSC “began its work of caring for the sick, doing other charitable work, and helping to bury the dead where financial help was needed.” One of the first major initiatives was purchasing land for a clubhouse on Hartford’s Blue Hills Avenue in 1910. The clubhouse doubled as a meeting place and boarding house for the elderly and migrant women and children. HBSC’s commitment to racial equality and Christian reform aligned with Ida’s investment in her community campaigns to provide for the most vulnerable of society.

Braxton’s club work went beyond her charity and mutual aid work; she was a champion of several political causes. According to the The Work Must Be Done project, Ida was among the early cohort of Connecticut African American reformers–including Mary Townsend Seymour, Mary A. Johnson, and Sarah Brown Fleming–who advanced voting rights in the decades leading up to the passage of the 19th Amendment.

The collective power of the Northeastern Federation and the club movement across Connecticut inspired Braxton’s commitment to voting. As a trustee of the HBSC, in 1918, she served on the planning committee for the historic Northeastern Federations convention under the theme “Votes For Women.” The convention was held at Shiloh Baptist Church, and the HBSC welcomed more than 200 delegates from across the region. According to documents in the “October 1920: The Women Who Led the Way” collection in the Hartford History Center of the Hartford Public Library, two years later, on October 13, 1920, Braxton and her relatives Winnie Braxton and Matilda Braxton were among the first generation of women to register to vote after Connecticut ratified the 19th Amendment on September 14, 1920. Braxton was a long-time member of the HBSC but also held membership in other civic organizations, including the Household of Ruth Lodge No. 214, the female branch of the all-black fraternal order, Grand United Order of Odd Fellows (GUOOF) Celestial Lodge No. 2,093, of which Moses was a member.

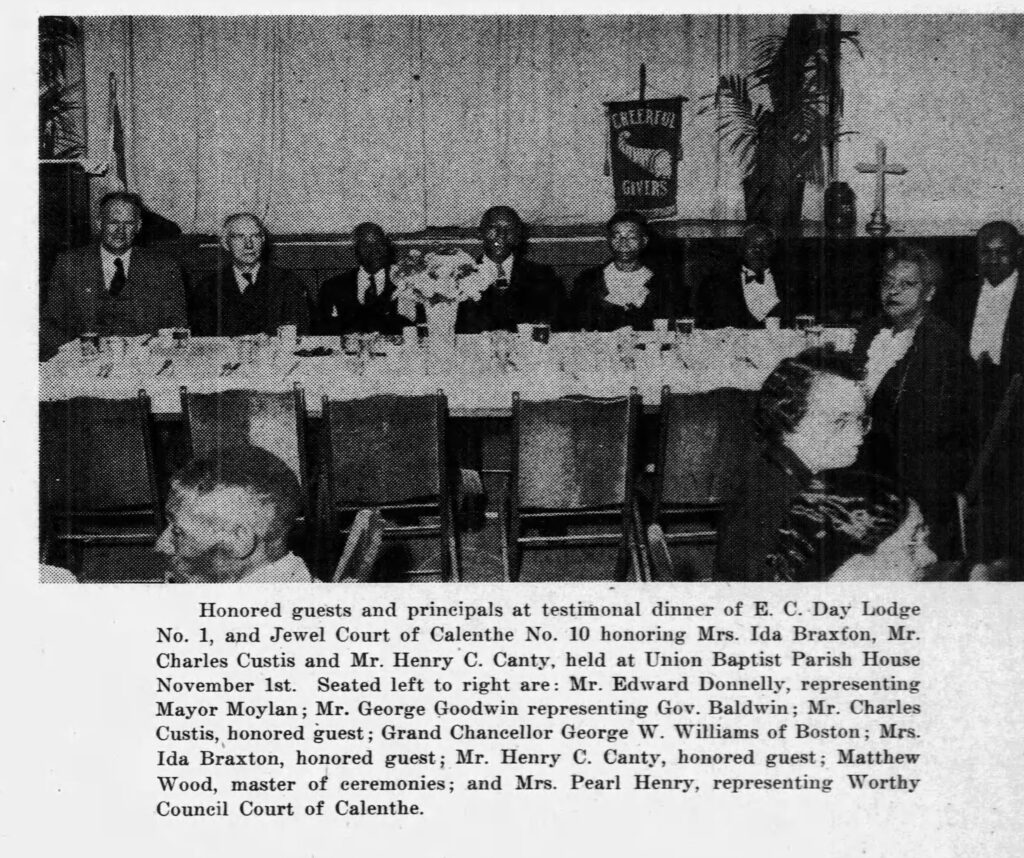

In 1925 Braxton suffered the tragic loss of her husband. On October 18 Moses left Union Baptist Church and was struck by a car on Capen Street on his walk home. As a widow, Ida continued her work in the HBSC and her other civic work until her death on October 29, 1951. At 82, Braxton died at her Capen Street home, then owned by her niece Anna Booze, a domestic worker for Katharine Seymour Day, a great-niece of Harriet Beecher Stowe who founded the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center in 1941. The Hartford Chronicle 1946 and New England Bulletin 1949 reported on d special honors and banquets celebrating her years of dedicated community work.According to The Hartford Courant, at the time of her death, Ida was “[T]he oldest living member of Union Baptist Church.” She is buried in the Spring Grove Cemetery in the heart of the Clay-Arsenal neighborhood.

Ida Holmes Braxton bridged piety and charity with equality and justice; her legacy reveals a rich history of black women’s activism in Connecticut.

Braxton (fifth from left) among the honorees at the Celestial Lodge No. 2093 Banquet at Union Baptist Church. Hartford Chronicle, November 9, 1946

Brittney Yancy is an assistant professor of 20th-century U.S. history at Illinois College. Her recent work is the digital archive project “The Work Must Be Done,” in partnership with the Connecticut Historical Society and funded by CT Humanities and the League of Women Voters.

Beth Burgess is director of collections and research at The Harriet Beecher Stowe Center.

Learn More!

The Hartford Black History Project

hartford-hwp.comhartford-hwp.com

“The Work Must Be Done: Women of Color and the Right to Vote Digital Archive Project,” Connecticut Historical Society, chs.org/research/wocvotes/

Listen!

“Uncovering African American Women’s Fight for Suffrage,” Grating the Nutmeg, gratingthenutmeg.libsyn.com/97-uncovering-african-american-womens-fight-for-suffrage