By Tom Schuch and Curtis K. Goodwin

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Winter 2022-23

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

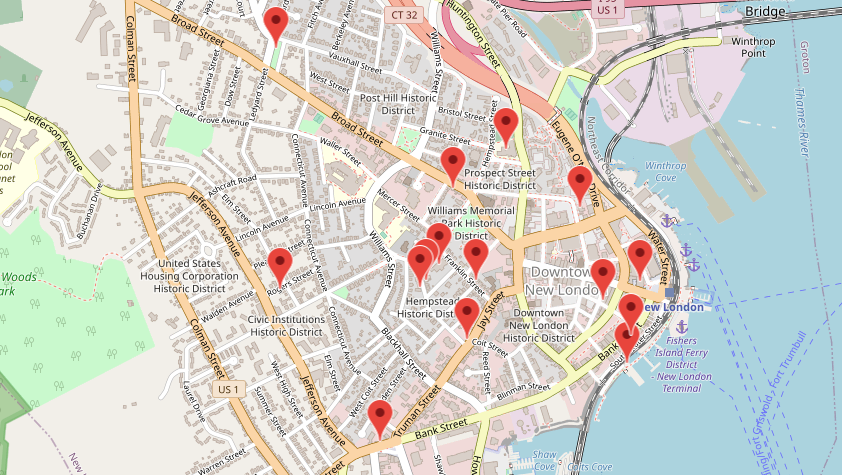

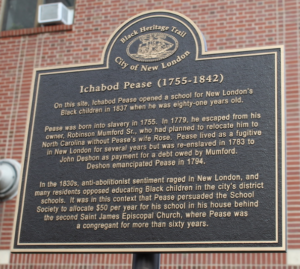

The New London Black Heritage Trail was officially unveiled on October 8, 2021, the result of a year-long collaborative effort led by former New London City Councilman Curtis K. Goodwin, the New London Economic Development Coordinator Felix Reyes, and a research team from New London Landmarks, along with other supporters. The Trail, a self-guided tour complete with audio narrations and some video accessed via QR codes, includes16 sites, each marked with a bronze plaque featuring a facet of the history of New London’s Black community. Together they tell a three-centuries-long story of Black resilience, resistance, and achievement. The Trail owes its existence to two serendipitous incidents: the accidental discovery in 2018 of the Ichabod Pease story by New London historical researcher (and co-author of this article) Tom Schuch and encouragement from another New London historian, Nicole Thomas, to her friend Curtis K. Goodwin (the other co-author) to attend an upcoming local lecture about Mr. Pease in summer 2019.

In an interview for this article, Goodwin said,“After attending the presentation on the discovery of Mr. Ichabod Pease, it became a tipping point that led to my fixation on fighting wrongs, both politically and historically.”

Who was Ichabod Pease? According to Benjamin Stark’s “Historical Sketch of New London Schools,” (New London County Historical Society,1895), Pease was “an aged colored man” who founded a school for New London’s Black children in his home on Church Street in 1837. Pease had been emancipated from bondage in 1794 at age 39. He started the school when he was 89, in the midst of a national—and local—controversy over abolition, education, and civil rights, while facing strong, racist local opposition, according to Stark [?]. But when he died in 1842, Stark notes, the city’s prominent men wanted to be pallbearers at his funeral,. Here was what appeared to be a remarkable story of courage, community, and resilience in the face of bigotry and oppression, one that had occurred at a critical moment in the nation’s history and yet it was virtually unknown in New London.

Goodwin was so inspired when he learned of the strength and resilience of Ichabod Pease, that he decided to run for public office – and to find a way to honor Pease. As he said in a video recorded by The New London Day at the unveiling of the Trail on October 8, 2021: “How did I not know the story of Ichabod Pease?” The fact that this inspirational story of a local hero hadn’t been taught in school was “a disservice to the children of all colors of New London.” He, along with the help of local historians and researchers, was determined to change that.

Once in office as a New London city councilor, Goodwin became chair of the city’s economic development committee. Together with Felix Reyes, and with the support of several local funding sources (the City of New London, Thames River Innovation Place, the State of Connecticut Office of Tourism, and the Eastern Regional Tourism District), he began to look for other, similarly inspirational stories of New London history.

In mid-2020 Goodwin and Reyes contracted Laura Natusch, executive director of New London Landmarks, who formed a team of researchers that developed a list of 25 additional stories about New London’s Black history. That research team consisted of Tom Schuch, Laura Natusch, Nicole Thomas, and local state’s attorney, historian, and lecturer Lonnie Braxton II. Goodwin and Reyes decided to focus on 15 sites that especially reflected the strength, resiliency, and sense of community that epitomized New London’s Black community over a span of 300 years.

The recently added 16th site is at the Amistad Pier, and more sites are in the early planning stages.

In addition to Pease’s story, the sites include a number of stories that are interwoven into the larger history of New London: the story of Adam Jackson, who was enslaved to the famous diarist and town leader Joshua Hempstead; Florio, wife of Hercules, one of Connecticut’s first known Governors of the Negroes, circa 1750; Antone DeSant, a Black whaler and successful New London businessman; Shiloh Baptist Church, the first Black church founded in New London; and several other significant buildings that housed fraternal and social welfare organizations that became centers of Black community life. These stories, unearthed by New London Landmarks staff working with the Black Heritage Trail researchers, were gathered from many sources, including the Diary of Joshua Hempstead of New London, Connecticut, Covering a Period of Forty-Seven Years, from September 1711, to November, 1758 (The New London County Historical Society, 1901), cemetery records, property records, newspapers, and city directories.

In addition to Pease’s story, the sites include a number of stories that are interwoven into the larger history of New London: the story of Adam Jackson, who was enslaved to the famous diarist and town leader Joshua Hempstead; Florio, wife of Hercules, one of Connecticut’s first known Governors of the Negroes, circa 1750; Antone DeSant, a Black whaler and successful New London businessman; Shiloh Baptist Church, the first Black church founded in New London; and several other significant buildings that housed fraternal and social welfare organizations that became centers of Black community life. These stories, unearthed by New London Landmarks staff working with the Black Heritage Trail researchers, were gathered from many sources, including the Diary of Joshua Hempstead of New London, Connecticut, Covering a Period of Forty-Seven Years, from September 1711, to November, 1758 (The New London County Historical Society, 1901), cemetery records, property records, newspapers, and city directories.

The sites also include stories of pioneering women like Sarah Harris Fayerweather, the first Black student at Prudence Crandall’s School in Canterbury, who, with her family, was active in the education, abolition, and civil rights movements in New London in the 1840s, according to information gleaned by Carl Woodward from Fayerweather‘s letters, held in the University of Rhode Island library.

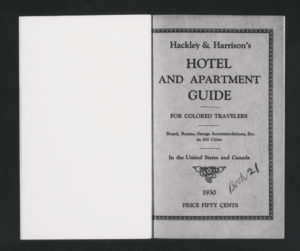

Another little-known story is that of Sadie Dillon Harrison, who with her business partner, lawyer Edwin H. Hackley, published the Hackley and Harrison Hotel and Apartment Guide for Colored Travelers in 1930-1931, working from her home on Hempstead Street. Candacy Taylor, in Overground Railroad: The Green Book and the Roots of Black Travel in America (Abrams Press, 2020), notes that the Hackley/Harrison Guide was the only precursor of the more famous Green Book travel guide, preceding it by seven years.

Two of the Trail sites honor contemporary leaders of New London’s Black community: Linwood Bland Jr., an outspoken civil rights leader, who in the 1960s and 1970s helped break the “color line” in housing in New London, in employment at defense giant General Dynamics Electric Boat, and in the local banking industry. He continued to battle for racial equity and justice into the 1990s, all of which he chronicled in his book, A View From the Sixties: The Black Experience in Southeastern Connecticut (New London County Historical Society, 2001),. His home on Franklin Street was recently restored as a landmark and converted to affordable housing by New London Landmarks.

Spencer Lancaster’s home on Rogers Street is the only site on the Trail for which a marker plaque was installed on private property. . It is also the only site on the Trail that highlights the resilience of a living figure. Mr. Lancaster was the first Black official elected to public office in New London. At 95 years, as of this writing, he remains the living embodiment of the loving dedication and community spirit that characterizes all of the sites on the Black Heritage Trail.

The New London Black Heritage Trail was introduced on October 1, 2021 at the national conference “Changing the Narrative,” hosted by the Slave Dwelling Project based in Charleston, South Carolina. One week later, the Trail was officially unveiled, with two public ceremonies at Black Heritage Trail sites: one honoring Spencer Lancaster at his home, and the second honoring Adam Jackson at The Hempsted Houses.

These sites are only a few of the historically important sites that have now been commemorated on the Black Heritage Trail. The original 15 sites can be viewed at the link below. A 16th site was unveiled on July 17, 2022, recognizing New London’s choice as a UNESCO Middle Passage Site of Memory, where captives were brought directly from Africa. New London (along with Middletown) is one of only two towns in Connecticut to be so designated.

Originally inspired by the determination of Ichabod Pease, the New London Black Heritage Trail has blossomed into a celebration of Black excellence, courage, and community spirit that reverberates through all 16 sites, honoring the contributions of the men and women, the churches and community organizations that helped form the foundation of today’s vibrant Black community.

From a single inspirational story, the Black Heritage Trail has grown into a tapestry of 300 years of New London’s Black community life. It is our hope that it will continue to be an inspiration for generations to come.

Tom Schuch is a New London native with a longstanding interest in social justice issues. His area of special interest has become unknown, hidden, forgotten, or suppressed local history.

Curtis K. Goodwin is a Black entrepreneur and consultant, and a former member of the City Council of New London.

Explore!

New London Black Heritage Trail

https://visitnewlondon.org/black-heritage-trail/