(c) Connecticut Explored Inc., Spring 2023

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

This article is adapted from Dougherty’s game-changing book On The Line: How Schooling, Housing, and Civil Rights Shaped Hartford and its Suburbs, an open-access book-in-progress for Amherst College Press. For the full version visit https://ontheline.trincoll.edu.

In Connecticut, the origins of exclusionary zoning can be traced back to efforts by the West Hartford town government to block a Hartford Jewish grocer from building a store in a residential neighborhood in the early 1920s. Although suburban leaders failed to block this store, they helped spark a statewide political movement for stronger legal tools to control future real estate development that excluded certain types of property — and people — that suburban residents deemed undesirable. West Hartford’s role in this history matters because, in 1924, the town raced to become the first Connecticut municipality to enact local zoning ordinances enabled by new state law. The town hired national experts to design a town-wide exclusionary zoning plan that set precedents followed by other suburbs in subsequent decades.

Zoning is key to understanding the history of where people live in our segregated metropolitan areas today. In general, “zoning” refers to rules governing how land can be used. Some policies have progressive goals, such as separating industrial factories from residential neighborhoods. In present-day debates, “exclusionary zoning” refers to policies that favor expensive single-family home construction that requires large amounts of property over more affordable multi-family homes that use less land per resident.

Through exclusionary zoning, West Hartford leaders created laws that intentionally made it more expensive to build homes in suburban neighborhoods, which effectively deterred lower-income people from living there. Unlike other discriminatory barriers of this era—such as mortgage redlining, restrictive covenants, and segregated public housing—exclusionary zoning did not directly refer to race, religion, or nationality. Instead, exclusionary zoning cleverly carved up suburban neighborhoods using minimum-land rules that segregated residents by their wealth. In this way, exclusionary zoning became a more sophisticated tool for housing discrimination that largely resisted the fair-housing legislation of the 1960s-1970s civil rights era and continues to divide Connecticut residents into the present day.

A Jewish Grocer and the Origins of Zoning in Connecticut

When Jacob Solomon Goldberg returned home to Hartford after military service in World War I, he sought to advance himself from a butcher to a businessman. Jacob partnered with family members to buy a small grocery store in downtown Hartford, near their East Side neighborhood, which they managed together during the early 1920s. Like other entrepreneurs of their era, Jacob and his partners told The Hartford Courant that they “followed the trend of business to the west,” and planned to open a second grocery store in the rapidly growing suburb of West Hartford.

That town’s population grew more quickly than Hartford’s during the 1910s, nearly doubling in size to almost 9,000 residents during that decade. West Hartford town officials granted more than 300 building permits for single- and two-family homes in 1922, more than any other town in Connecticut that year, according to the Connecticut State Board of Education. Linked by convenient trolley lines to the capital city, with its corporate headquarters for the nation’s leading banks and insurance companies, West Hartford was quickly becoming an ideal destination for the rising middle class. The emerging suburb, adjacent to Hartford’s premier West End neighborhoods, was politically independent, and its real estate opportunities became a magnet for the elite.

That town’s population grew more quickly than Hartford’s during the 1910s, nearly doubling in size to almost 9,000 residents during that decade. West Hartford town officials granted more than 300 building permits for single- and two-family homes in 1922, more than any other town in Connecticut that year, according to the Connecticut State Board of Education. Linked by convenient trolley lines to the capital city, with its corporate headquarters for the nation’s leading banks and insurance companies, West Hartford was quickly becoming an ideal destination for the rising middle class. The emerging suburb, adjacent to Hartford’s premier West End neighborhoods, was politically independent, and its real estate opportunities became a magnet for the elite.

In the early 1920s, only a dozen grocers served all of West Hartford’s population, including several small shops where owners sold food products out of their homes. Customers typically made frequent purchases from neighborhood grocers during the week due to limited transportation and refrigeration.

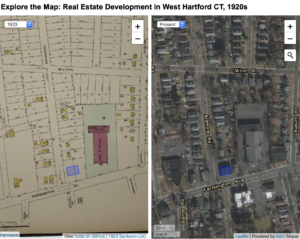

Goldberg and his family searched for the perfect West Hartford location. With funds from his parents, who opened one of Hartford’s first kosher meat markets in the 1880s, the Goldbergs bought two valuable parcels of undeveloped land on Farmington Avenue at the corner of Ardmore Road, on the trolley line about halfway between the Hartford border and West Hartford’s town center. Goldberg’s closest competitors were located about a half-mile in opposite directions: West Hill Grocery (also on Farmington Avenue, closer to the Hartford border) and M.J. Burnham’s (a larger store in West Hartford Center). Although the immediate area around Goldberg’s property had only 60 houses in 1923, real estate developers and town officials had subdivided the land into smaller lots and were building side streets and sewer lines in anticipation of many more homebuyers. Next door to Goldberg’s vacant lots stood the only non-residential building in the vicinity: the West Hartford Armory for the Connecticut National Guard Troop B Cavalry, built in 1913.

But when Goldberg applied for a building permit in January 1923, the West Hartford building inspector refused to grant it. Instead, the inspector called a public hearing, where “a score of property owners in the Ardmore Road section appeared and protested” against Goldberg’s plan to build a grocery store, according to The Hartford Courant. In their eyes, it made no difference that Goldberg had hired a respected local architect whose design followed every legal requirement in the town building code. It made no difference that his proposed store would be facing the busier Farmington Avenue or occupy much less space than the Armory building next door. What mattered was that property owners objected to Goldberg’s right to build a store in their neighborhood, and the town government took their side by declining to grant a permit.

But when Goldberg applied for a building permit in January 1923, the West Hartford building inspector refused to grant it. Instead, the inspector called a public hearing, where “a score of property owners in the Ardmore Road section appeared and protested” against Goldberg’s plan to build a grocery store, according to The Hartford Courant. In their eyes, it made no difference that Goldberg had hired a respected local architect whose design followed every legal requirement in the town building code. It made no difference that his proposed store would be facing the busier Farmington Avenue or occupy much less space than the Armory building next door. What mattered was that property owners objected to Goldberg’s right to build a store in their neighborhood, and the town government took their side by declining to grant a permit.

Why did West Hartford property owners and town officials block Goldberg’s building permit? Were they opposed to a grocery store in their residential neighborhood—or to the presence of a Jewish grocer from Hartford? The best answer is both. During this period of rapid growth, challenging Goldberg’s grocery was a way for West Hartford neighbors and leaders to share their fears about “undesirable” urban influences infringing on their suburb and threatening their property values. Some objected to business development, some resented immigrant outsiders, and Goldberg symbolized both.

The local controversy over Goldberg’s store arose during a period of intense anti-Jewish and anti-immigrant fervor across the nation. By 1920, around 30 percent of Hartford’s population were foreign-born immigrants, with Russians, Italians, Irish, and Poles as the largest groups. Hartford became home to Connecticut’s largest Jewish community, estimated by scholars Sandra Becker and Ralph Pearson to be about 11 percent of the city’s population. In Protestant-led small towns like West Hartford, even if no one publicly uttered an anti-Jewish slur against Goldberg, some local officials and property owners most likely perceived him as a Jewish Hartford outsider to their community.

In 1919 Governor Marcus Holcomb launched Connecticut’s Department of Americanization, and the state-funded Connecticut Americanizer publication, with a mission to convert “our foreign-born and illiterate population.” He wanted to adopt what former President Theodore Roosevelt envisioned as “one common language, one country, one allegiance, one loyalty and one flag” and to live in a culturally unified nation, “not as dwellers in a polyglot boarding house.” Most of Hartford’s recent Jewish immigrants lived in crowded multi-family tenements in the Front Street and Windsor Street neighborhoods near the Connecticut River. Progressive-era reformers declared these to be “the worst housing conditions in the country” among cities of Hartford’s size, and placed photographs in public reports that visually represented the “undesirable” urban elements that suburban leaders strongly sought to avoid.

For the Goldberg family, owning a retail business was the best route to the middle class because Hartford’s most prestigious institutions in finance, medicine, and law generally refused to employ Jews in higher-status positions. Although the city was one of the nation’s centers of banking and insurance, companies such as The Hartford, Aetna, and Travelers only hired a few Jews to serve as bookkeepers or sales agents and did not allow them to rise into positions of authority until the 1950s. Both the Protestant-run Hartford Hospital and the Catholic-run St. Francis Hospital barred nearly all Jewish doctors, with rare exceptions, from practicing medicine at their facilities until World War II. Similarly, Hartford’s top three corporate law firms at that time—Robinson, Robinson & Cole, Day, Berry & Howard, and Shipman & Goodwin—refused to employ Jews through the 1950s. Although these “gentleman’s agreements” to exclude Jews typically were unwritten, occasionally we can find them in private documents. For example, at a closed-door meeting with board members of Trinity College in 1915, President Rev. Flavel Luther openly described what he called “the problem presented by the slow, but unmistakable increase of the number of Jews at the College,” which took steps to reduce Jewish enrollment through at least 1922. Overall, anti-Semitic barriers established by Hartford’s leading institutions led many Jews to pursue success through independent small businesses.

Jacob Goldberg and his allies fought back against West Hartford town leaders. He hired an attorney and filed a lawsuit against the town in January 1923, challenging the constitutional authority of the local government to refuse to grant a building permit on the arbitrary grounds that “neighbors do not want it.” Initially, West Hartford Town Council members assigned their attorneys to fight back. But behind the scenes they gradually realized that Goldberg had a strong case. Without a clearly defined policy, a court might rule against the town and reduce its authority over land-use decisions in the future. Goldberg eventually prevailed when town leaders granted him a building permit, and he opened the Kingswood Market grocery store in 1924. Although Goldberg won this battle, West Hartford leaders concluded this episode by announcing the creation of a brand-new zoning commission in July 1923. While the concept of “zoning” was not yet clear, local leaders hoped it would offer a more legally defensible framework for preventing what they deemed to be undesirable urban elements from entering their rapidly growing suburban community.

Bringing Zoning to West Hartford

In the aftermath of the Goldberg controversy, West Hartford leaders lobbied Connecticut legislators for a law allowing local governments to enact zoning ordinances to control future land development. Town council member Josiah Woods urged suburban residents to support a zoning bill, based on Herbert Hoover’s national model, “to protect the residential character” of designated areas. In 1923, when the Connecticut General Assembly voted for “An Act Concerning Zoning in Certain Cities and Towns” – which initially granted local powers to only seven municipalities across the state — West Hartford moved quickly to become Connecticut’s first municipality to design and enact its local zoning ordinance.

The West Hartford Town Council appointed Josiah Woods to chair its zoning commission in mid-1923 and hired consulting services from two nationally prominent experts: zoning attorney Edward Bassett and urban planner Robert Whitten. Their plan for West Hartford not only separated industrial, commercial, and residential areas, as zoning had been commonly defined. Instead, they went further by using zoning to economically segregate residential areas through minimum-land rules that favored neighborhoods with more expensive single-family homes and physically distanced them from less expensive multi-family housing and apartment buildings.

The West Hartford Town Council appointed Josiah Woods to chair its zoning commission in mid-1923 and hired consulting services from two nationally prominent experts: zoning attorney Edward Bassett and urban planner Robert Whitten. Their plan for West Hartford not only separated industrial, commercial, and residential areas, as zoning had been commonly defined. Instead, they went further by using zoning to economically segregate residential areas through minimum-land rules that favored neighborhoods with more expensive single-family homes and physically distanced them from less expensive multi-family housing and apartment buildings.

Whitten crafted the 1924 West Hartford Zoning report to blend the soft rhetoric of inclusion with hard rules of exclusion. The introduction promised that zoning would bring “orderliness” and “efficiency” to the town’s rapid growth, with “an increase of health, comfort and happiness for all people.” It recognized that the suburb’s primary function was to provide housing for people who worked in the adjacent city of Hartford and to serve “all classes and all grades of economic ability,” including “factory workers, office employees, and the various business and professional groups.” But deep inside the body of the report, Whitten devised a system to sort residents into economically segregated, homogeneous neighborhoods.

Whitten crafted the 1924 West Hartford Zoning report to blend the soft rhetoric of inclusion with hard rules of exclusion. The introduction promised that zoning would bring “orderliness” and “efficiency” to the town’s rapid growth, with “an increase of health, comfort and happiness for all people.” It recognized that the suburb’s primary function was to provide housing for people who worked in the adjacent city of Hartford and to serve “all classes and all grades of economic ability,” including “factory workers, office employees, and the various business and professional groups.” But deep inside the body of the report, Whitten devised a system to sort residents into economically segregated, homogeneous neighborhoods.

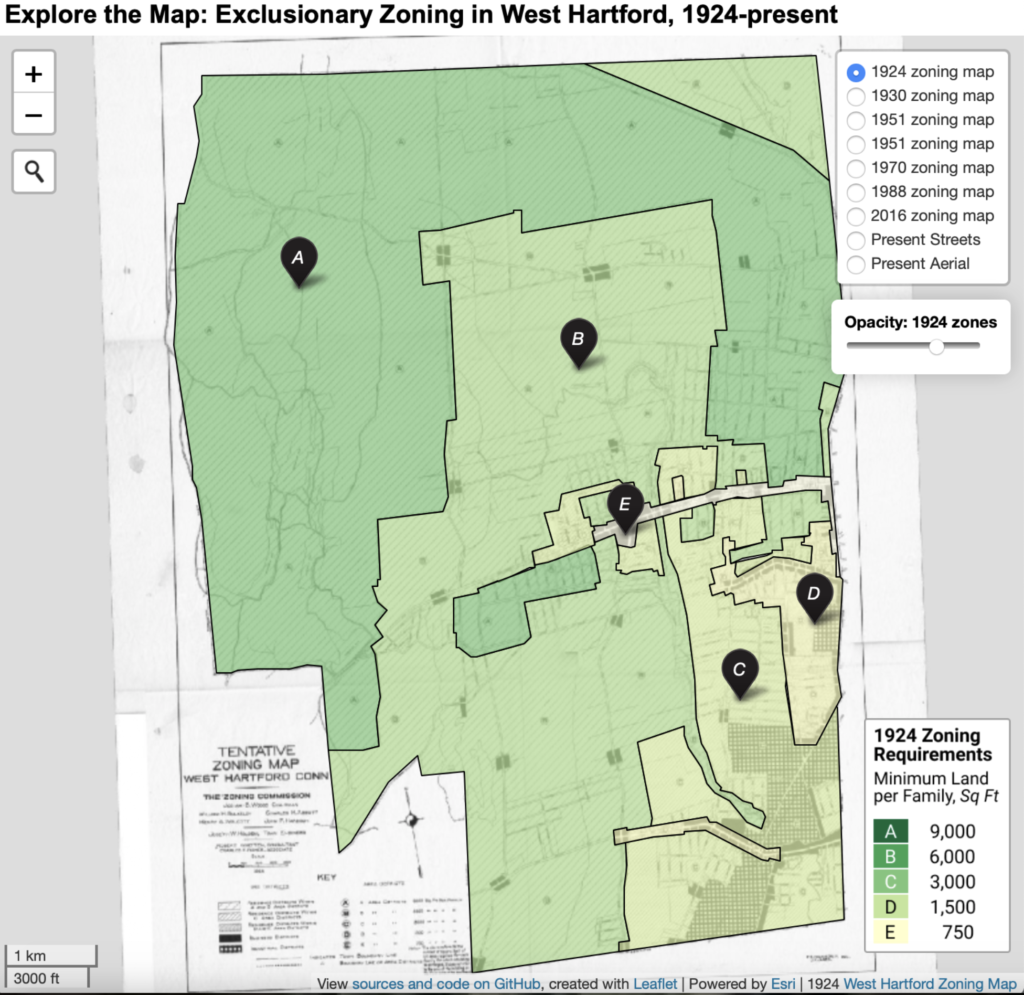

Whitten’s zoning plan divided West Hartford into five residential areas—A, B, C, D, and E—based on new rules that required a minimum amount of land per family to construct housing. The most exclusive A zones were designated for upper-income single-family homes because they required at least 9,000 square feet of land (one-fifth of an acre) per family. At the opposite end were the C, D, and E zones, set aside for more affordable multi-family duplexes, triples, and apartments, where the rules required significantly less land per family. Additional rules increased the amount of land needed to build in more exclusive areas: A-zone homes could occupy no more than 30 percent of the property lot and must be 60 feet wide on the street-facing side. While these 1920s rules may seem modest by today’s standards, Whitten recommended nearly twice the amount of land per family in West Hartford’s most exclusive zone compared to similar zones in Cleveland and Atlanta because Connecticut’s suburbs offered more space for large-lot zoning requirements.

Overall, West Hartford’s 1924 zoning formula relied on minimum-land rules to create separate neighborhoods for expensive single-family homes and affordable multi-family homes and to physically distance these residents from each other. The 1924 report clearly stated its objectives. Zoning policy would make it “uneconomic to build two-family houses” in A and B areas because real estate developers needed to buy twice as much land compared to the amount needed for a single-family home. Given the same land costs, developers would generate more profits by building and selling two single-family homes rather than one two-family home. While “three-family houses and apartments houses are not prohibited in the A, B, or C area districts,” the report clarified that zoning would influence the marketplace by removing incentives to build mixed-income housing. In short, the new rules rewarded developers who built economically exclusionary neighborhoods.

Exclusionary zoning was designed to sharply reduce the amount of multi-family housing that developers would build. Although West Hartford’s zoning plan did not prohibit multi-family housing, it pushed lower-income families into lower-rated C, D, and E areas—the only zones where duplexes, triples, and apartments could be constructed economically—which sharply limited the supply of affordable housing in the suburb. The 1924 West Hartford Zoning report cautioned readers about multi-family housing taking over suburban space that should be reserved for single-family homes. It featured photographs with captions warning that “large apartment houses are spreading farther west along Farmington Avenue and into side streets,” the same areas as the Goldberg grocery store controversy the year before. Through minimum-land rules, the report promised that “crowded tenement house conditions [that]exist in many larger communities,” such as the city of Hartford, “will be effectively prevented in West Hartford.” Words and images in the report were clearly intended to stir up anxieties among suburban homeowners about multi-family urban tenements and their “undesirable” occupants.

Expanding Zoning Across Connecticut

Although Connecticut’s 1923 state law initially justified zoning because of public health and welfare concerns, West Hartford leaders and their consultants refined its purpose to attract higher-income homebuyers and protect their property values. Suburban leaders quickly embraced zoning as a legally defensible strategy that enabled local governments to segregate or exclude what they viewed as “undesirable” urban influences—on the basis of wealth—without directly referring to their race, religion, or nationality. In this way, zoning became a powerful and long-lasting tool of government-sponsored housing discrimination that continues to the present day.

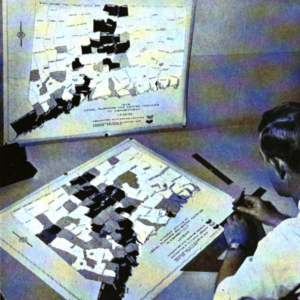

After Connecticut legislators allowed town governments to enact zoning regulations in 1923, local land-use policies spread quickly across the state. While each town made its own decisions, the growth of zoning was tracked by the Connecticut Development Commission, a state agency created in 1939 to promote economic growth and efficient planning for industry and housing. The commission published a series of maps to illustrate the growth of local planning and zoning agencies in Connecticut. Towns that enacted local zoning policies tended to be clustered in the rapidly growing suburbs around the state’s major cities of Hartford, Bridgeport, and New Haven. By 1957, 77 percent (131 out of 169) of town governments had established some type of planning and/or zoning agency. Nearly every town within a 20-mile radius of Hartford—including outlying rural areas far from the city center—enacted some type of land-use agency to exert control over what kind of housing could be built in their community.

During the 1950s suburban towns began to compete against one another by establishing more exclusive zoning requirements – such as a minimum of 87,000 square feet of land (about 2 acres) to construct a single-family home – to attract higher-income homebuyers. Similarly, many suburban towns began to expressly prohibit the construction of more affordable multi-family homes to keep out lower-income residents. Uncovering the roots of our state’s zoning history helps us understand present-day political battles to end exclusionary practices led by statewide advocacy groups such as the Connecticut Fair Housing Center, the Open Communities Alliance, and Desegregate Connecticut.

Jack Dougherty is Professor of Educational Studies at Trinity College.