By W. Phillips Barlow and Elena Pascarella

By W. Phillips Barlow and Elena Pascarella

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2018

SUBSCRIBE/BUY THE ISSUE!

Frederick Law Olmsted Sr. has long been recognized as one of America’s greatest landscape architects, with a legacy of beloved parks and outdoor public spaces across the nation. Recognized as the father of landscape architecture in America, in a prolific career he designed not only Central Park but also the United States Capitol Grounds, Boston Fens, Stanford University Campus, Prospect Park in Brooklyn, New York, the suburb of Riverside, Illinois, and the grounds of the 1893 Columbia Exposition.

What many do not know is that he is a Connecticut native, that he was raised in Hartford’s North End, and that he is interred in Hartford’s Old North Cemetery. Olmsted very definitely left his mark in Connecticut, creating parks and private commissions in New Britain, Hartford, and Bridgeport and residential commissions in 11 towns. Major parks and properties designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in our state (with various partners) include Walnut Hill Park (New Britain), Keney Park and the grounds of the Institute of Living (Hartford), and Seaside and Beardsley parks (Bridgeport).

Olmsted had lofty goals and aspired to bring the rural countryside to urban dwellers. He believed that the parks he created were places where people from all walks of life could come together to enjoy fresh air, panoramic views, and the inspirational beauty of nature. He further believed in the transformational power of nature and the ability of public parks to enrich people’s lives.

Olmsted was born on April 26, 1822 on Ann Street in Hartford. He was the first child of John Olmsted, a successful dry-goods merchant, and his wife, Charlotte Law Hull Olmsted. Both were from established families in the area. His mother died in 1825, soon after the birth of Frederick’s brother John. His father soon remarried (he married his brother’s widow), and the family grew. In his autobiography, Olmsted fondly remembered his youth:

I can see that my pleasure began to be affected by conditions of scenery at an early age, long before it could have been suspected by others from anything that I said and before I began to mentally connect the cause and effect of enjoyment in it. It occurred too, while I was but a half-grown lad, that my parents thought well to let me wander as few parents are willing their children should.”

This was not a child with nature-deficit disorder. Later in life he recalled that “most of this time was spent fishing and hunting in the countryside.”

One of his joys as a child was traveling with his family “in search of scenery.” The family traveled often through the Connecticut River Valley and to New York State and the Maine coast. As Olmsted later wrote:

The happiest recollections of my early life are the walks and rides I had with my father and the drives with my father and mother in the woods and fields. Sometimes these were quite extended, and really tours in search of the picturesque.”

Time spent at his mother’s family’s farm, Brooks Vale Farm, in Cheshire had a great influence on his future career. The farm belonged to David Brooks, who married Olmsted’s aunt (his mother’s younger sister).

Brooks Vale Farm is currently a 55-acre site on the north side of South Brooksvale Road. The property originally consisted of more than 300 acres, encompassing the house, barns, and farm fields. Family letters provide documentation that both Olmsted and his brother John spent time at the farm during their childhood and that they at least once walked the 30 miles from their home in Hartford. There is no documentation that Olmsted later provided any formal designs for Brooks Vale Farm, but records and family lore indicate that he planted a grove of hemlock trees (Tsuga canadensis) approximately 200 feet west of the house.

Olmsted attended schools in several Connecticut towns and studied surveying in Collinsville. In the fall of 1845 he attended lectures at Yale College in New Haven, and for experience in farming he worked and studied at a farm in Waterbury. Farm work presented an opportunity to learn first-hand the skills of grading and drainage, which would later help him immensely in his career as a landscape architect.

In 1846 his father bought him a farm on Sachem’s Head in Guilford. The 70 acres extended down to the rocky edge of Long Island Sound, and Olmsted spent the spring preparing the land. The Reverend Horace Bushnell, among others, visited Olmsted at the farm.

In the 1850s he traveled widely and toured the American South as a reporter for The New York Times. He published travel books and articles arguing that the practice of slavery was economically inefficient and not sustainable. He also operated a farm on Staten Island. For a brief time he was managing editor of Putnam’s Monthly Magazine. In fall 1857 he became superintendent of New York City’s Central Park; after his brief tenure there, he and Calvert Vaux won the design competition for the park, which was completed around 1865.

Walnut Hill Park, New Britain

Walnut Hill Park, New Britain

In April 1857 Frederick Stanley (founder of the Stanley Works) wrote to the warden of the Borough of New Britain with a proposal to build a water works for the city. The plan included a reservoir at the summit of Walnut Hill, where the altitude would provide sufficient pressure for hydrants.

Stanley had begun work on the project in 1856. In that year he acquired 36 acres of land on Walnut Hill from the bankrupt estate of O. Burnham for three thousand dollars. The land was described at the time as “exceedingly rough and uncultivated barren, not fertile enough for pasture and supporting nothing but the rankest growth of weeds, used chiefly in the winter for coasting purposes.”

In 1857 The Walnut Hill Park Company (the entity that Stanley had formed to carry out the development) transferred the reservoir and access roads to the Town of New Britain without cost to the town. The motivation of the shareholders was to create a city park with “the finest recreational and cultural amenities.”

From 1857 to 1862 The Walnut Hill Park Company made drainage and road improvements to the property. Progress was slow, and Stanley grew impatient with the town’s failure to initiate development of a park. He soon took matters into his own hands and contacted Olmsted, asking him to visit the park and provide a plan. In his letter Stanley stated that “the city would entertain no other designer than Olmsted.”

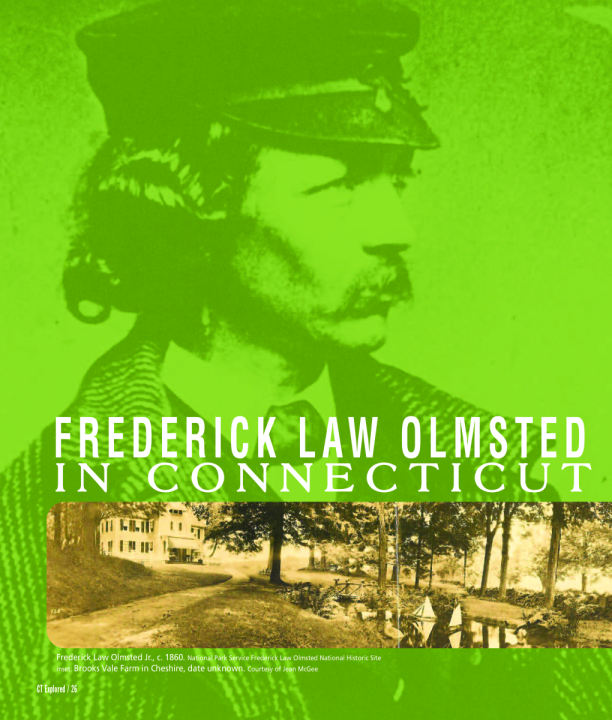

Olmsted traveled to New Britain in August 1867 and recommended the acquisition of additional property to the west and southwest of Walnut Hill. The additional 40 acres of land would provide some flat land for the park, in addition to the hill. Olmsted subsequently agreed to provide a plan, completing it in 1870. The design called for three main areas: The Bergmonte Close (the top of the hill), the Commons (the western meadow), and the Fountain Close (the southwest portion of the site).

The Commons is a typical Olmstedian meadow of turf and trees surrounded by a meandering roadway. A grove of trees anchors each end of the meadow. Today the Commons provides space for much-used ball fields.

The Fountain Close, also typical of an Olmsted plan, provided a formal foil to the informal, naturalistic layout of the majority of the park. The plan depicts a large fountain surrounded by terraces and formal plantings. Olmsted’s endorsement of the Fountain Close seems to have been halfhearted; in his final report he states, “If the feature is not built, the park will not suffer.” The Fountain Close was in fact never built, and today a detention pond occupies the area originally intended for the feature.

At the top of the hill stands Bergmonte Close. (It is not clear where the name came from.) Olmsted called for a scenic overlook with a meandering walkway following the slope down to West Main Street. Although the overlook was never built, a 90-foot-tall limestone obelisk was built at the spot in 1930. Designed by the renowned memorial architect H. Van Buren McGonigle, the obelisk honors New Britain sons who gave their lives in World War I.

The park’s construction took several years, with work stopping and starting as the economy rose and fell. City leaders had the good sense in 1908 and 1921 to engage what had by then become the Olmsted Brothers firm to inspect the park construction. The historical record shows that on both occasions Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. was generally pleased with the way his father’s vision was being implemented. Minor complaints included “the tendency to place trees in rows” and the difficulties of grading an access drive so that the side banks were harmonious with the rest of the park.

Other than the addition of a monumental band shell and some formalistic plantings, Walnut Hill Park remains remarkably true to the vision that Olmsted laid out in 1870. The park, now listed on the National Register of Historic Places, is beloved, with more than 50 events held yearly and hundreds of thousands of visitors, according to Stephanie Scalise of the New Britain Parks and Recreation Department.

Trinity College, Hartford

It may come as a surprise that Olmsted was involved with the Trinity College campus, albeit it not as successfully as with his work in New Britain.

At the time when the college was moving from its campus adjacent to Bushnell Park (selling the site for $600,000 to the State of Connecticut, which built the state capitol there) several properties were under consideration. Trinity College trustees initially asked Olmsted to develop criteria for evaluating the campus sites; they were divided as to which was the best location for the new campus. Trinity President Thomas Pynchon and the trustees then engaged Olmsted to advise on the specific properties under consideration.

Olmsted recommended the Blue Hills Road site. In his hand-written, 21-page report, in 1872, he states that “The Blue Hills site has the greatest apparent eminence, and a group of large buildings set upon it would be seen from a greater distance on all sides than either of the other sites.” For unknown reasons, the trustees did not heed Olmsted’s advice, and they made an offer of $2,000 for the Penfield Farm site on the north side of Park Street. The bid was ridiculously low and was not accepted.

A detailed plan by Olmsted protégé landscape architect Jacob Weidenmann was then prepared for the Farmington Avenue site, but the trustees opted to purchase the Summit Street site for $225,000. The site occupied high ground with sweeping views, but cheap boarding houses, a gravel pit, and a cemetery surrounded it. In addition, the students considered the site to be excessively far from the city center, according to The History of Trinity College, Volume 1 (Glenn Weaver, 1967).

In spite of the rejection of Olmsted’s initial recommendations, in 1873 he was asked by Trinity president Rev. Abner Jackson to advise on the Summit Street campus. Olmsted again ran into disfavor, as his recommendation included the necessity of acquiring several adjacent properties. Once again, the trustees ignored his advice and did not purchase the land at that time.

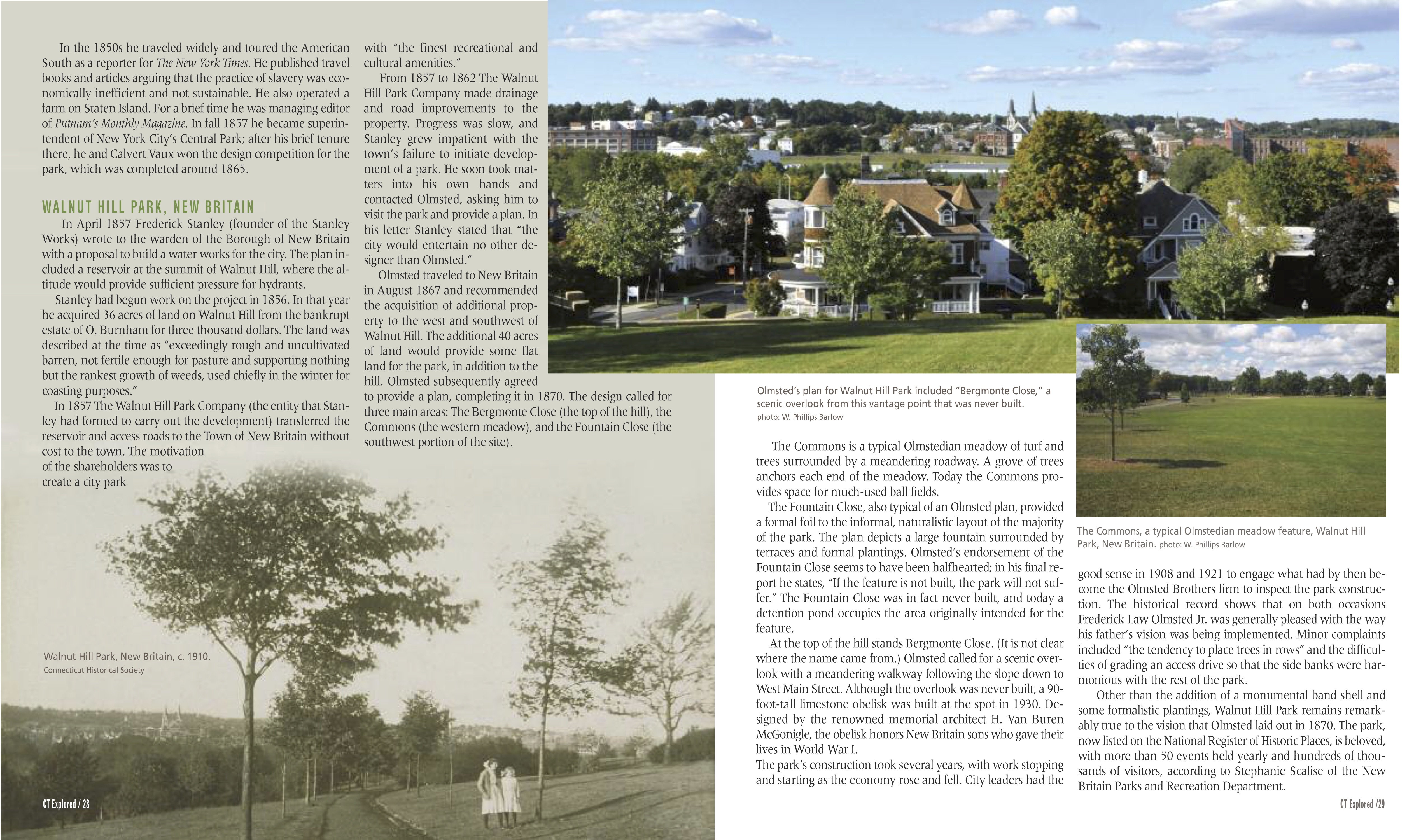

Records in the Trinity archives include references to Olmsted’s being engaged again in 1875 to landscape and lay out campus grounds. The Olmsted Archives has many topographical studies, preliminary sketches for the campus, a plan for the layout and planting of Summit Street, and numerous reports and correspondence. A detailed sketch shows the Long Walk terrace abutting Summit Street looking much as it appears today. In his definitive history Trinity College in the Twentieth Century (Trinity College, 2000) author Peter Knapp notes that Olmsted advised architect Francis H. Kimball on the siting of the Long Walk building along the Summit Street ridge, suggesting that he position it along a north/south axis. Knapp also reports that in 1883 Olmsted recommended that the trustees plant a line of trees perpendicular to the existing line of elms at the Long Walk, forming a distinctive “T” pattern. After succumbing to Dutch elm disease, the elms were replaced in 1977 with Marshall’s seedless ash trees. Olmsted and his sons remained involved at Trinity College until the early 1890s. In 1893 the firm produced a plan for “A Parkway West of College Building” (Summit Street).

Like much of his best work, Olmsted’s contribution to the development of the Trinity College Campus is subtle and nuanced. Although he advised on the campus’s development for more than 20 years, today his contributions to the development of the lovely campus are not well known.

Residential Work

Olmsted’s residential work in Connecticut was not extensive or well documented. His residential designs were mostly for suburban communities for the urban middle class, which was retreating from the oppressive conditions of 19th-century cities. The Olmsted Archives in Brookline, Massachusetts lists 11 residential projects in Connecticut completed by Olmsted or his sons for individuals or housing developments including the Moorland Hill subdivision for Stanley Works in New Britain, Bridgeport Housing Company in Bridgeport, Pine Orchard in Branford, and family housing at the U.S. Navy Submarine Base in Groton.

In 1903, after a long illness, Olmsted died in the Massachusetts McLean Hospital. His family placed his ashes in the family vault at Hartford’s Old North Cemetery. The firm that he had established continued under the leadership of his son Frederick OlmstedJr. and stepson John Olmsted. Operating as Olmsted Brothers Landscape Architects, the brothers proved to be ideal partners and formidable landscape architects in their own right, expanding the Olmsted legacy. In fact, the legacy of the Olmsted Brothers in Connecticut is perhaps stronger than that of their father, as they completed many park and institutional projects across the state. The firm continued operating until 1961 as Olmsted Brothers and until 1980 as Olmsted Associates.

Phillips Barlow, ASLA, is the founding principal of TO Design LLC, a landscape architecture and urban planning firm in New Britain. Elena Pascarella, ASLA, is the principal of Landscape Elements LLC. Both have worked on projects at Frederick Law Olmsted and Olmsted Brothers sites in Connecticut.

Explore!

Read more stories about Connecticut’s historic landscape and Notable Connecticans on our TOPICS pages.