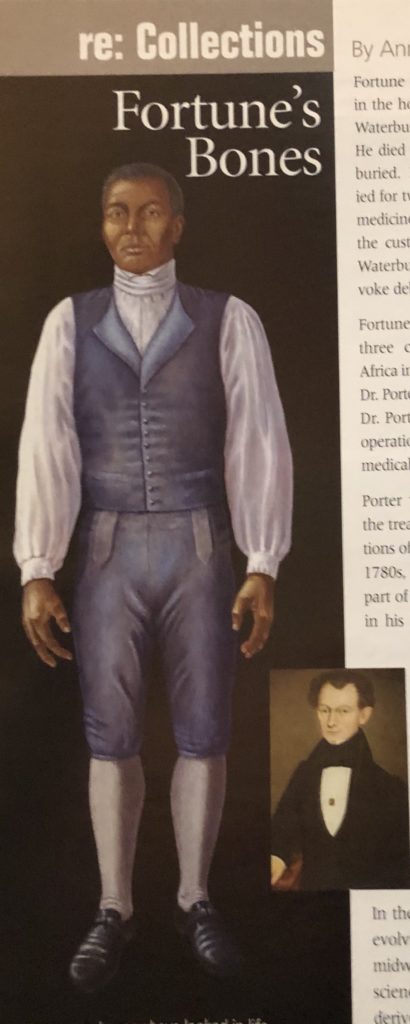

Fortune as imagined, based on his skeleton, by medical illustrator William Westwood, c. 2007. Fortune was probably 5′ 7″ tall. inset: Dr. Jesse Porter by Erastus Salisbury Field, c. 1830-35. He inherited Fortune’s skeleton from his father Dr. Preserved Porter. Mattatuck Museum, Waterbury

By Ann Y. Smith

(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Spring 2007

Subscribe/Buy the Issue!

Fortune was an African American man enslaved in the household of Dr. Preserved Porter in Waterbury, Connecticut in the 18th century. He died in 1798, but his remains were not buried. Instead, his skeleton has been studied for two centuries, offering insights into medicine, science, and history. Currently in the custody of the Mattatuck Museum in Waterbury, the skeleton continues to provoke debate about our past and his future.

Fortune and his wife Dinah lived with their three children and Fortune’s older son Africa in a small home owned by Fortune on Dr. Porter’s property. He probably worked on Dr. Porter’s 75-acre farm, running the farm operations while Porter concentrated on his medical practice and real estate speculation.

Porter was a physician who specialized in the treatment of bones, as did three generations of Porter physicians before him. In the 1780s, when Fortune and his family were part of the Porter household, Dr. Porter was in his 50s, raising young children of his own. One of Porter’s younger children, his son Jesse who was born in 1777, studied medicine with his father when he came of age late in the 18th century and continued in the family business, serving as a physician in Waterbury until his death in 1860.

In the 18th century, colonial medicine was evolving from the traditional practices of midwives, folk healers, and herbalists to a science based on anatomical knowledge derived from dissection and the direct observation of the human body. Trained by Scottish physicians immersed in the perspective of the Enlightenment, advocates of this new approach began offering anatomical lectures in Newport and Philadelphia by the middle of the 18th century. The first American medical school was established in Philadelphia in 1764 to promote these new techniques.

Even rural physicians who did not have the resources to study in colonial cities or European colleges were eager to establish their connections with this more modern approach to medicine. They acquired books about anatomy and, when possible, anatomical specimens. To demonstrate his up-to-date credentials in 1783, for example, a Rhode Island doctor announced the opening of his practice by inviting the public to visit his office and see his wired skeleton, prepared from the body of an “executed Negro.”[1]

Porter was a believer in this new scientific approach. He was a founding member of the Medical Society of New Haven County in 1784, a select association that testifies to his interest in professional medical practices and his status as a recognized practitioner.

Acquiring anatomical materials to support this new kind of study, however, was problematic. In the 17th and 18th centuries, English law in most colonies prohibited the digging up of bodies—a protection against witchcraft—with obvious implications for medical studies. At the same time, common law in colonial New England allowed the bodies of executed criminals to be made available for anatomical study. Some state legislatures specifically permitted judges to sentence those convicted of capital crimes and other offenses to be dissected as further punishment beyond death.[2]

Yet there continued to be a shortage of bodies available for medical study, and physicians and medical students sought cadavers wherever they could be found. These bodies typically belonged to those whose position in society placed them among the disenfranchised in life: Native American prisoners of war, people hanged for capital offenses, prostitutes, suicides, and enslaved people.

Connecticut lawmakers grappled with the demand for corpses for medical research and the competing public outrage over the use of bodies for this purpose. In 1810 the state prohibited grave-robbing for medical dissection, but the practice continued. Riots broke out in New Haven in 1824 when it was learned that students at the medical school had taken the body of a recently deceased young woman from her grave in West Haven. The Governor’s Foot Guard was called out to control the violence when her remains were found in the cellar of the medical school.[3] When the Connecticut legislature passed an act permitting the dissection of unclaimed bodies in 1833, public protest led to the repeal of the act in 1834.

At the time of Fortune’s death in 1798, Porter would have been 69 years old and probably retired from the active practice of medicine. However, his 21-year-old son Jesse was just beginning his medical practice and would have benefited from the opportunity to study a skeleton. Fortune’s skeleton was valuable, priced in the doctor’s estate at $15, higher than the value of Fortune’s surviving widow Dinah, who was valued at $10.[4]

Nineteenth-century historians report that Porter prepared the skeleton for use in his School of Anatomy in Waterbury. While there is no evidence that such a school existed, the bones were indeed preserved and cleaned. Several were labeled in a fine 18th-century script. Subsequent generations of Porter family members recalled early anatomy lessons aided by study of the skeleton. One of Porter’s descendants wrote to the director of the Mattatuck Museum that she had received her first medical instruction as a child, when her father taught her the names of the bones using Fortune’s skeleton “just as the Porters were taught in the ages gone before.”[5]

Given Fortune’s status as a slave, Porter may have felt entitled to the use of his body in death as in life. Apparently, Porter was not dissuaded from using the skeleton by his relationship with Fortune or his ongoing relationship with Fortune’s wife and children, who continued to live as members of the Porter household until the elder Porter’s death in 1803. Nor is there evidence of any negative reaction from the community, who seem to have been aware of the slave skeleton’s presence throughout the 19th century.

The skeleton remained in the possession of subsequent generations of Porter physicians until 1933, when Sally Porter Law McGlannan, a descendant of Preserved Porter and one of the earliest female graduates of Johns Hopkins Medical School, donated it to the Mattatuck Museum.

In the 1990s the museum worked with a team of community advisors and scholars to understand Fortune’s life and its broader implications. The museum’s African American History Project Committee, led by Maxine Watts, guided these activities. Scholars included the late Gretchen Worden, former director of the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia, Susan Lederer, Yale University School of Medicine Section of the History of Medicine, and Toby Appel of the Yale School of Medicine historical archives. Anthropologists Dr. Warren Perry of Central Connecticut State University and Leslie Rankin Hill of the University of Oklahoma assisted in the analysis of the skeleton.. Based on the findings of anthropologists, forensic artists, and historians, the museum’s permanent exhibition about Fortune’s story presents an image of the 18th-century world of African Americans, enslaved and free, in Waterbury. Connecticut Poet Laureate Marilyn Nelson was commissioned to write Fortune’s Bones: The Manumission Requiem (Front Street, 2004). Her moving poem was transformed by Dr.Ysaye Barnwell into a cantata that was performed in Waterbury and at the University of Maryland. Additional research and curriculum materials are available on the project’s Web site, FortuneStory.org, created by Raechel Guest. Research is ongoing.

[1] 1773 Providence Gazette and Country Journal, quoted in Michael Sappol, A Traffic of Dead Bodies (Princeton:Princeton University Press, 2002)

[2] Sappol, A Traffic of Dead Bodies.

[3] Rachel Engers, “Anatomy of an Insurrection” in Yale Medicine (Spring, 2002)

[4] Preserved Porter’s estate inventory, 1804. Collection of the Connecticut State Library, State Archives.

[5] McGlannan files, Mattatuck Museum Collection Records, Waterbury, Connecticut.

Explore!

Read more stories about the African American experience in Connecticut on our TOPICS page.

Read more stories about Connecticut’s medical history in our Spring 2007 and Feb/Mar/Apr 2004 issues.