(c) Connecticut Explored Inc. Winter 2018-2019

Subscribe/Buy the Issue

Ellis Walter Ruley (1882 – 1959) was born in Norwich, Connecticut, the son of freed slaves. He became an artist who was little recognized in his day but whose works are much loved by collectors today. His life and work and the Norwich community’s recent embrace of his story are celebrated in Brought to Light: Ellis Walter Ruley in Norwich, on view at the Slater Memorial Museum through December 7, 2018.

Ruley worked as a mason’s assistant, carrying stone all day. An injury in a work-related motor-vehicle accident in 1929 changed the course of his life. An insurance settlement left him with the means to pursue his artistic impulse virtually full time and as a vocation.

It may have been this newfound financial comfort that also drove Ruley in the 1950s to offer his work for sale during the Norwich Art Association’s annual Art in the Open event, held on the lawn of the Slater Memorial Museum. Ruley’s art was displayed on snow fence and offered for the modest sum of $15 per work. Even then, the price was a bargain, the equivalent of less than $130 today. Any local collector who acquired a painting directly from Ruley and retained it into the present era made an excellent investment, as today his work is much sought-after by collectors.

The Norwich Record (October 12, 1952) sang Ruley’s praises and credited the Norwich Art Association for bringing his “modern primitive style” to light. One member of the Art in the Open committee was Joseph Gualtieri, then an art teacher at Norwich Free Academy (home to the Slater Memorial Museum), who would become, a decade later, the Slater Museum’s director. It may have been at that event that Gualtieri discovered Ellis Ruley. An unattributed article in the Norwich Evening Record (September 13, 1953) reports on the Second Annual Art in the Open show, gushing that “Ellis Walter Ruley was on hand with his highly original artworks in the primitive school. Mr. Ruley again attracted a large audience of his own and sold as much as any artist present.” The following show, in 1953, may have been his last Art in the Open appearance; his name does not appear in lists of participating artists from 1954 through 1957, the event’s final year. In 1956, Ruley’s work was displayed in the NFA Art School, on the ground floor of the Converse Art building, andin 1980 Gualtieri included Ruley’s work in Connecticut Black Artists, an exhibition at the Slater Museum.

Brought to Light presents an opportunity to appreciate once again Ruley’s broad appeal to the current day, to explore the impulse of collectors to collect work by Ruley and other so-called outsiders, and to learn how they acquired the work. Norwich native Michael Goldblatt owns one work by Ruley. “My mother acquired the painting circa 1953,” he wrote in an e-mail to me. “She hung it in my bedroom so I kind of grew up with the picture. Thankfully I did not lose track of the painting and had it nicely framed about 16 years ago. I keep it on the wall in my office and appreciate it every day.” He further explained that “My mother, Dorothy Goldblatt, was an accomplished artist herself, primarily doing pastels and still lifes. She exhibited at several local art shows including the Lyman Allyn Art Museum show held at Connecticut College. Dorothy was introduced to Ellis Ruley by Joseph Gualtieri. … Mr. Gualtieri and my mother appreciated Ellis Ruley’s work long before he became recognized beyond the local community.”

Since the 1950s Ruley’s work has attained considerable value and is held in the collections of individuals and such museums as The Amistad Center for Art & Culture, the American Folk Art Museum, The Smithsonian, and, of course, the Slater Memorial Museum. Significant credit for Ruley’s collectibility goes to author and filmmaker Glenn Palmedo-Smith, an early collector who published Discovering Ellis Ruley(Crown, New York, 1993), which led to an important traveling exhibition of the same name in 1996.

In his book Palmedo-Smith describes acquiring his first work by complete happenstance at a flea market at Brimfield, Massachusetts in 1990. He does not shy away from revealing his early buyer’s remorse, which was appeased ultimately by the magnetism of the piece.The c. 1940s Adam and Evecompelled Palmedo-Smith to become the artist’s biographer. He pursued a decades-long quest to promote the merit of Ruley’s work and to urge officials to re-open the investigation into the artist’s mysterious and violent death. In January 1959 Ruley’s bloody, frozen body was found at the bottom of his long, winding driveway in Norwich, but his death was ruled accidental by police, and no one was ever charged.

The Wadsworth Atheneum hosted the traveling exhibition Discovering Ellis Ruley, curated by Stephen L. Brezzo ofthe San Diego Museum of Art and sponsored by the Ford Motor Company, in 1996. The book, exhibition, and Palmedo-Smith’s advocacy inspired an upward spiral in the value of Ruley’s works.

Discovering a previously unknown artist of merit must surely be exhilarating and rewarding. In the 20thcentury “outsider” artists generally also fell into the category of self-taught, primitive, or naïve. In the U.S., many of these artists were, in addition, “outside” the mainstream of American life: people of color, artists with few material resources, or even artists with mental illness. Grandma Moses, Bill Traylor, Howard Finster, Sam Doyle, and Martin Ramirez are notable “outsider” artists who come quickly to mind. It is not unusual to find that such artists’ family members have ignored or taken for granted the talent that is later perceived by collectors. Too often an artist’s life’s work is discarded, or barely saved by a third party with a good eye. In some cases works of art and family memorabilia are jettisoned as useless detritus. With luck, these find their way into the hands of pickers, auctioneers, or dealers. With greater luck, they are deposited at the doorsteps of museums and historical societies.

Frank Mitchell, executive director of The Amistad Center for Art and Culture,is pleased to share the center’s works by Ruley in Brought to Light, noting that “working with our partners in Norwich feels like the realization of a project imagined by our founding collector, Randolph Linsly Simpson. It feels like a suitable legacy project honoring both Ruley and Simpson.” In 1987 the Wadsworth Atheneum acquired a group of objects from Simpson that later formed The Amistad Center’s collection. The collection included photographs, books, artifacts and documents, and three paintings by Ruley. Simpson, a white man living in North Branford, collected objects relating to the African American experience for more than 25 years, from about 1945 to 1970. A second, also considerable, portion of his collection went to the Beinecke Rare Book Library at Yale in 1989. According to the Beinecke’s website, Simpson “developed a deep appreciation for African-American culture that dates to his childhood in Rochester, New York. His passion for collecting grew over the years, fueled by a desire to preserve the material record of black history in America, which was rapidly disappearing.”

It is not known how or when Simpson acquired the three works by Ruley. Mitchell notes that Simpson “returned to Connecticut after his service in World War II and continued collecting the work of regional artists. Simpson educated himself at area art fairs, community exhibits, and auctions. He was committed to Ruley and other regional artists whose work referenced African-American realities. Because he was an early collector of Ruley’s work, Simpson later received calls from other enthusiasts hoping to authenticate their paintings. His devotion to African American arts and culture made him a good choice for consultation.” One of those enthusiasts was Palmedo-Smith, who contacted Simpson after purchasing Adam and Eve. Simpson connected him to Gaultieri, who authenticated the work.

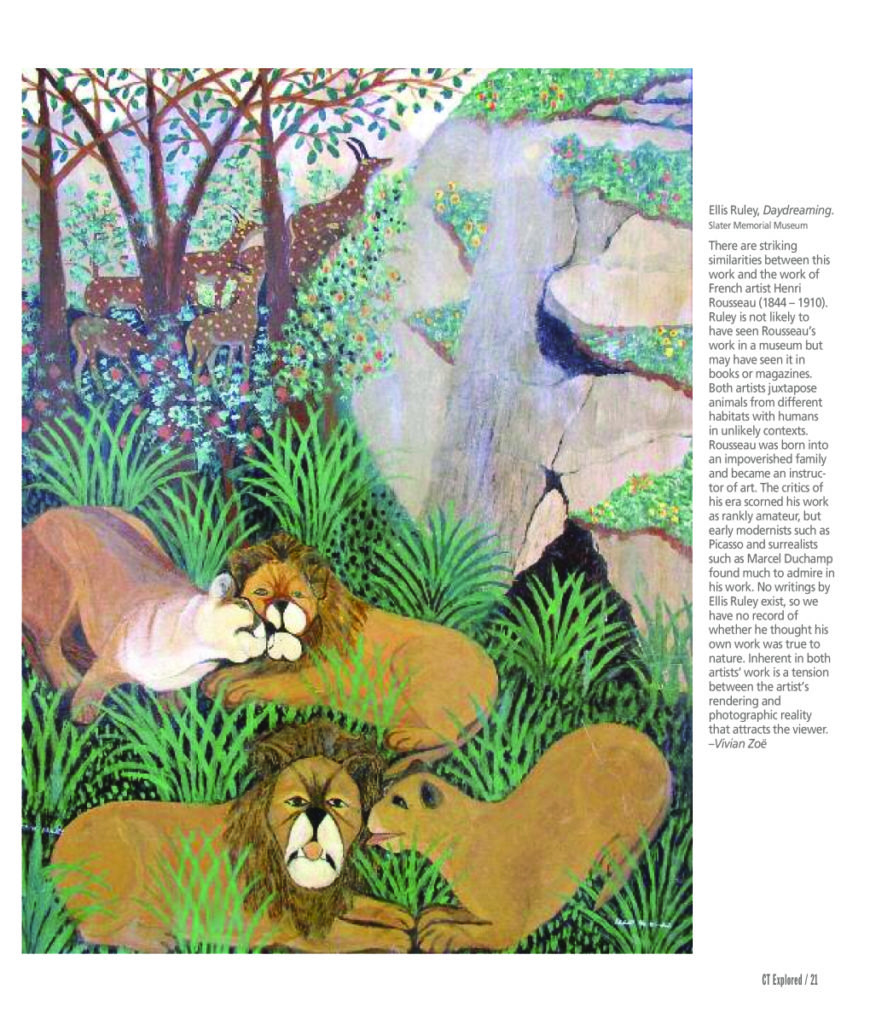

For Discovering Ellis Ruley, Palmedo-Smith depended heavily on folk-art scholars Lee Kogan, Stacy Hollander, and Gerard Wertkin of the Museum of American Folk Art and Barbara Hudson, then curator of African American art at The Wadsworth Atheneum and director of The Amistad Center for Art & Culture. Their contributions describe in detail the appealing elements of Ruley’s work—painted in house paint on board—, including its seemingly light-hearted themes such as animals living in harmony together, happy farm workers picking abundant fruit, and bathing beauties enjoying fun in the sun. It seems a nearly universal phenomenon that those who acquired Ruley’s work before it became collectible were drawn to its bold, colorful, and unreserved style.

In 1981 John Ollman, then curator at Janet Fleisher Gallery in Philadelphia, purchased a box of paintings from a dealer in Rhode Island, recalling that they had been stored so poorly that some had stuck together. Undaunted, he salvaged what he could, finding a trove of work by Ruley. That’s when the commercial market for Ruley’s work emerged. Another collector bought the now iconic Adam and Eveat a Rhode Island estate sale. The painting eventually made its way to Brimfield—and to Palmedo-Smith.

After Ruley’s death, his house burned. Some later said that a sizeable number of his works remained in the house at the time of the fire, an uncorroborated assertion. Those who recalled his selling his art at Art in the Open remember the snow fencing loaded from end to end with work. His family recalled that Ruley painted every day. But the known number of his works today is estimated to be 63 or fewer.

Among the collectors who loaned worked to Brought to Lightare Josh Feldstein, Josh Jerit, and a third collector who prefers to go unnamed in print. They shared with me why they love Ruley’s work and their advice for budding collectors of outsider art.

Josh Feldstein of Gainsville, Florida loaned his entire Ruley collection to Brought to Light; among the works is Waterfall. Waterfall imagery is one that repeats in the Ruley oeuvre. This particular work shows a mighty stream zigzagging its way through a lush hillside. Feldstein acquired his first Ruley around 1995 from Janet Fleisher Gallery. His collecting focus is on “untrained” American artists—their creativity without training being what inspires him. He only sells work when there’s no room left on his walls and he wants a new piece. He’s never sold a Ruley. Feldstein’s advice to beginning collectors is to “buy what you love and buy the best. Use books to train your eye and then have confidence in your eye. You will know it’s great from your gut.”

John Jerit of Tennessee loaned three Ruleys to the exhibition, including Mrs. Grey Owl and Her Pet Beaver. The painting depicts a woman of brown skin fondling the animal as if it were a cat. Despite Ruley’s own African heritage, only about a quarter of his human subjects are noticeably non-white. Jerit acquired his first Ruley around 2003 or 2004, when he traded with Josh Feldstein, whom he had met at art and antiques auctions. Jerit appreciated Ruley’s naïve style and found the artist’s personal story interesting. He was particularly drawn to Ruley’s use of color. Jerit began studying Palmedo-Smith’s book and traveled to see his collection.

Jerit’s advice for beginning collectors is to “Buy what you love and love what you buy. A work of art will never look better than it does on display in a gallery, so be sure you love it.” He says he is a slow buyer who takes his time to make a decision, but once he has, he is committed to it. Jerit laments that collectors of folk art are getting older and are starting to sell or give their collections to museums. He fears their collections could go into permanent storage in museums, where they might be rarely seen.

The third collector, who loaned six paintings to Brought to Light, is from the Midwest. Among those is Cheif [sic]Grey Owl + Wifewhich depicts the brown-skinned couple having set firearms down in a lush forest, extending their arms heavenward as if worshipping Mother Nature. This collector had a strong and early interest in Ruley, collecting his work beginning in the early 1980s. He acquired all that John Ollman had in stock. (Ollman by then had bought out Janet Fleisher.) Although his collecting tastes and interests are broad, he says he likes Ruley’s work in particular because he finds the subject matter unusual for an African American artist. His first purchase of Ruley’s work was his last. Remarkably, the works were not on display in Ollman’s gallery, but the wise collector asked if there was anything to see beyond what was on view. It proved a good strategy. He started his diverse collection in the mid-1970s, has loaned to numerous museums, and was partially responsible for the 1996 Wadsworth Atheneum exhibition that toured the country.

Frank Maresca, director of the Ricco/Maresa Gallery in New York that deals in “outsider” art (but did not loan works to Brought to Light), wrote in an e-mail to me, “I think ultimately everyone who buys art is probably looking for some degree of the ‘truth.’ …We have found that the work of artists who are operating outside of society and the art historical continuum is closest to the bone. These artists are not aware of, or concerned with, getting reviews in national newspapers, or interested in being represented by fashionable galleries, so the result is a genuine quality that collectors and art lovers are drawn to.”

“In the case of Ellis Ruley,” Maresca continued, “we are talking about such an artist; someone who visually spoke the truth about race relations in an age when the depiction of playful and often erotic imagery between blacks and whites (particularly by black artists) was virtually unknown and considered taboo. Still, Ruley never hesitated to tell the truth, often disguising a potentially explosive situation in a compelling manner—it is speculated that Ruley faced the ultimate consequence for his imagery when he was found dead [near his home]. It is not that the truth is the exclusive realm of the Self-Taught or Outsider artist, it just seems that it is easier to disregard or break the unspoken rules of society and the artificial parameters of academia when you are not aware of them in the first place.”

On July 27, 2018 Ruley’s home site was dedicated as a City of Norwich public park. The dedication ceremony was joyously attended by dozens of citizens, Glenn Palmedo-Smith, and novelist and native son Wally Lamb. The sense of closure was palpable. Harry Ruley II, Ellis Ruley’s great grandson, had proposed such a memorial beginning in the 1970s, lobbying Norwich City Council repeatedly for four decades. The park is interpreted with text panels about the artist and the home that once stood on the site. Last year school children in Norwich and Three Rivers Community College art students used Ruley’s art as inspiration for their own. These works will be displayed alongside Ruley’s in Brought to Light. Later this year a group of high-school students from Norwich Free Academy will perform a play written specifically for this occasion and commissioned by the Ellis Walter Ruley Commemoration Committee of the City of Norwich.

Vivian Zoë is executive director of the Slater Memorial Museum at the Norwich Free Academy. She last wrote “The Slaters Go Round the World,” Winter 2011/2012.

Explore!

Slater Memorial Museum

108 Crescent Street, Norwich

nfaschool.org/home

John Denison Crocker: Norwich’s Renaissance Man, Winter 2006-2007

Ellis Ruley Memorial Park

28 Hammond Avenue, Norwich

The Amistad Center for Art & Culture

600 Main Street, Hartford

Amistadcenter.org

More art history from Connecticut Explored!

Winter 2004-2005: Connecticut’s Art History 101

Winter 2006-2007: Connecticut’s Art History 102